A train operator (or subway pusher?) holds onto rail as a window is busted open showing a packed train

Imagine a city whose suburbs have outsized the core in a span of few years. Thanks to an economic boom and a severe housing crunch, residents are increasingly pushed to the outer ring of the city. Due to an influx to the outer areas, train services quickly become outstretched to its limits. Crowds pack the trains during rush hour, leaving no wiggle room inside cars. Decades of lack of major investments exacerbate the issue. Frustrations mount at the lack of progress.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, these were predicaments ailing probably any North American metropolis. But this scenario sums up an unlikely city in an unlikely time: Tokyo in the 1960s.

Thanks to a massive population boom in the 15 years after World War II, Tokyo and its satellite cities – such as Saitama, Yokohama and Chiba – saw their populations nearly double in total from 9.78 million in 1945 to 17.86 million in 1960. Despite a population expanding outwards to find affordable housing, the main work centers remained in the core of Tokyo. This growing job-to-housing imbalance in the suburbs put severe pressure on the long-standing regional rail lines in the Greater Tokyo Area.

In 1965, the Japanese National Railways launched arguably its most transformative rail infrastructure project in postwar Japan not named Shinkansen: the Commuting Five Directions Operation (通勤五方面作戦, tsukin-gohomen-sakusen). It was an ambitious package of infrastructure improvements to significantly add capacity on five trunk lines connecting Tokyo to nearby cities in five directions. This was accomplished through any means necessary: adding extra tracks on the same right-of-way; diverting rider demands with new lines and extensions; and/or separating or even seizing freight lines to make space for passenger rail lines. This was a marked change in JNR’s approach to regional rail as well, a full pivot from a JNR which once claimed this is an issue metropolitan governments should entirely handle with better distributed housing policies and projects.

The work in total took nearly two decades to complete. While crowded trains in Tokyo never went away (the “subway pushers” were a thing then and a thing now), JNR’s goal of relieving crowding – with expected population growth accounted for – was accomplished, as all five lines saw crowding percentages decrease despite ridership increasing manifold. In addition, the substantially added capacity unlocked many new potentials in Tokyo’s rail network which became integral to its regional economy and quality of life. In the grand scheme, it became the skeletal foundations from which a thriving and profitable JR East, the privatized descendant of JNR, was able to blossom from.

A commute on the Chuo Line, also nicknamed “Murder Line”. Watch the whole video

Methodology and Background

Unlike my Seoul Metro Line 9 post, which made heavy use of my Korean mother tongue, Japanese is a language I have no familiarity with. Research took three-plus months of collecting sources in Japanese (or English, as occasionally lucky) as broadly as I can and translating them all using Google Translate — and mostly translating again somewhere else if the passages are translated nonsensically. The scarcity of English written materials on Japanese rail history has been very frustrating, and this has proven to be a very labor-intensive post to research and write.

I fully acknowledge that I may have blind spots or inaccuracies in this report easily identifiable to those who are fluent in Japanese or in Japanese rail history. As a former newspaper reporter, I gave my due diligence to this work but I will happily review any requests to correct any factual inaccuracies and clarify any mistranslation or misunderstanding.

I also made the difficult decision to split the piece into two to better allow both to shine on its own merits. Part II will focus on the legacies of the Commuting Five Directions Operation.

A Quick Geography Lesson

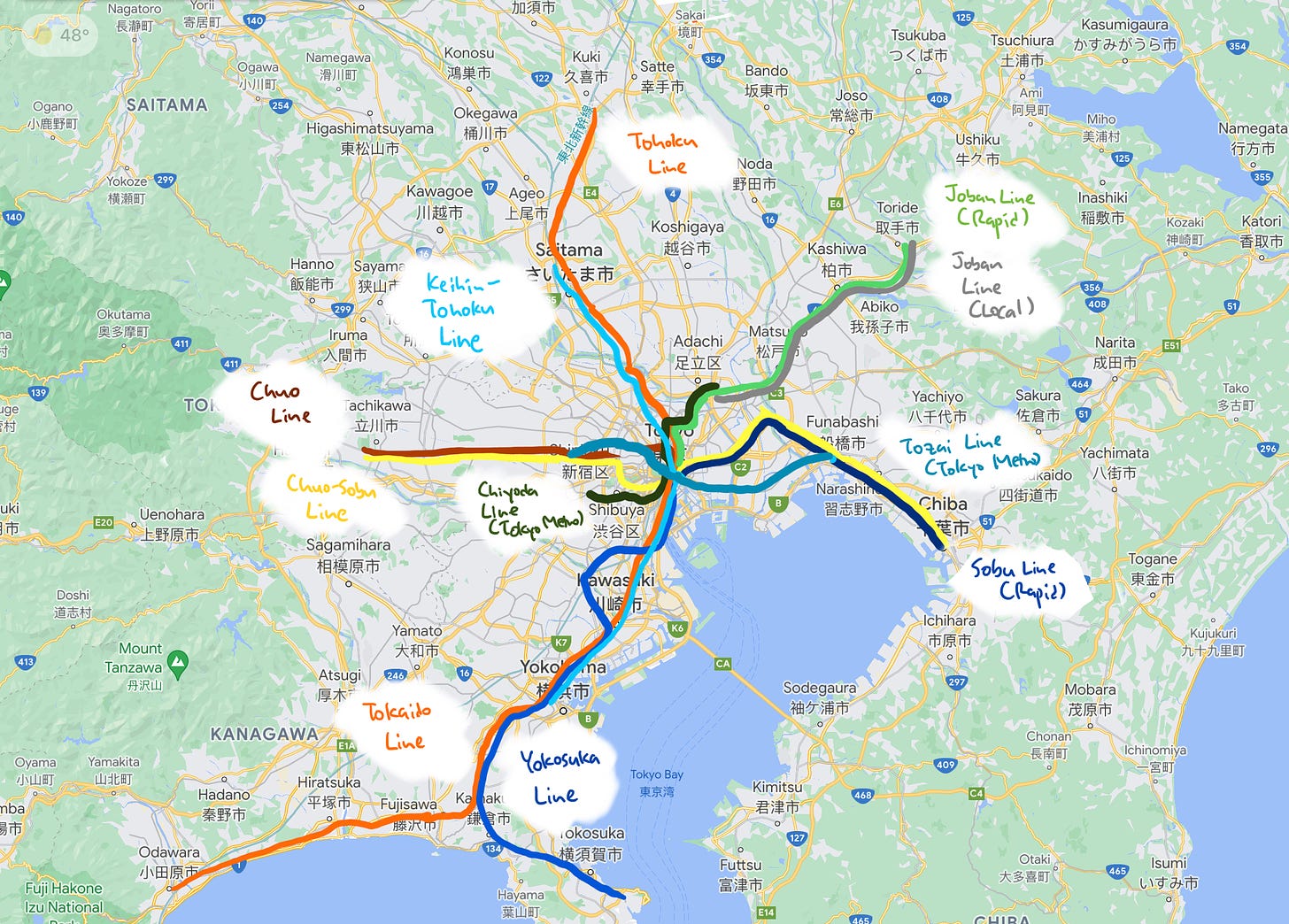

Tokyo is a sprawling metropolis with so many satellite cities and train lines that it can be easily intimidating to follow along. Japanese rail networks are commonly identified by a line name, often either a portmanteau of two endpoint cities or just the terminus point. I will not be able to list nor delve into the several dozen passenger rail lines which crisscross the Greater Tokyo Area. But I do want to take a moment to identify the train lines I will be referring to repeatedly and the directions they go from central Tokyo as a compass for the reader:

Five main lines:

-

Tokaido Line: Runs southwest from Tokyo.Full route connects to Osaka and Kyoto. The regional line connects Tokyo to Yokohama and Odawara (near Mt. Fuji)

-

Chuo Line: Runs west from Tokyo in a straight line.

-

Tohoku Line: Runs north from Tokyo. Connects Tokyo to Saitama.

-

Joban Line: Runs northeast from Tokyo.

-

Sobu Line: Runs east from Tokyo. Connects Tokyo to Chiba

Secondary lines:

-

Yokosuka Line: Runs south from Tokyo. Runs parallel with Tokaido Line from Tokyo until Ofuna and turns east.

-

Keihin-Tohoku Line: Runs north-south through Tokyo. Connects Saitama, Tokyo and Yokohama. Runs on both Tohoku Line and Tokaido Line

-

Chuo-Sobu Line: Runs west-east through Tokyo, does NOT go through central Tokyo. Runs on both Chuo and Sobu trunk lines

-

Chiyoda Line (Tokyo Metro): Connects southwest suburbs of Tokyo (including Shinjuku) to northeast suburbs of Tokyo. Runs parallel to Joban Line in northeast side

-

Tozai Line (Tokyo Metro): Connects west and east of Tokyo through Koto City and Edogawa sitting by the Tokyo Bay. Its two terminus stations – Nakano in the west, and Nishi-Funabashi in the east – also are Chuo-Sobu Line stations.

A hand-drawn regional rail lines of the Greater Tokyo Area to show its orientation and clarity in understanding the Commuting Five Directions Operation. Not every small directional turns for every line may be entirely accurate but I vouch for its directional accuracies.

Tokyo’s Rebirth and its Metropolitan Crises, 1945-1965

In 1945, the year Japan unconditionally surrendered to the Allies in World War II, the Greater Tokyo Area was hollowed out in population by the near-daily bombings and economic destruction. The Greater Tokyo Area’s population (which includes the four Tokyo, Saitama, Chiba and Kanagawa prefectures) dropped 27% from its 1940 peak from 12.74 million to 9.37 million; Tokyo alone saw a 48% decline from 7.35 million to 3.49 million.

Japan – and Tokyo, especially – recovered from its postwar ruins at breakneck speed. Thanks to the Korean War from 1950 to 1953, Japan’s industrial production expanded rapidly, with factories, plants and offices mushrooming inside Tokyo’s city limits. By 1950, the Greater Tokyo Area recovered its wartime population loss at 13.05 million. By 1960, the area added nearly 5 million residents at 17.86 million.

For the first 15 years of postwar recovery, Japan focused on providing massive amounts of public housing to address both rapidly growing demand in the war-scarred Greater Tokyo Area and the existent poor quality housing stock constructed organically out of postwar ruins. Shoddily built and densely packed wooden apartments proliferated in Tokyo; a dense area of these buildings were formed around the popular ring-shaped Yamanote Line earning the moniker “wooden rental apartment belt.” To replace unplanned and high-disaster risk housing stock, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government and other newly formed public housing corporations built massive quantities of high-rise public housing as close to the city center as possible.

In the 1960s, the Japanese government adjusted its housing policies as worker income and standard of living quickly rose. The government began pushing for home ownership and began building massive construction projects in the outer parts of the Greater Tokyo Area. Public housing projects in Tokyo city limits proved increasingly difficult to construct as land prices soared in Tokyo under a booming economy.

The 1960s brought new transportation modes to Tokyo. Higher worker incomes fueled the appetite for the automobile. The number of privately-owned automobiles in Tokyo tripled in eight years, from 490,000 in 1959 to 1.54 million in 1967. Under the guise of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, the Japanese government funded expressways and wider roads for the car to better roam the metropolis. As the Tokyo streetcar network was sacrificed to make space for the car, Tokyo aggressively expanded its subway lines to buffer its urban mass transport systems. In the 1960s, five lines for both Tokyo Metro and Toei Subway opened. (Including the Chiyoda and Tozai Lines which we will visit later)

The automobile or the new subway lines could not ameliorate the growing crisis in the most popular mode of transport in the Greater Tokyo Area: regional rail lines. Despite some of the lines being the oldest in Japan, regional lines carried the growing weight imposed by Japan’s suburbanizing housing policy, the continued jobs concentration in central Tokyo and displacement of Tokyo residents to the suburbs due to rising rents. From 1955 to 1964, Tokyo’s western suburbs and surrounding prefectures added 830,000 daily commuters to an already packed commute ridership.

The government-owned Japanese National Railways (JNR) tried in vain to improve the commute experience. They introduced new modernized rolling stock – the 101, 111 and 113 electric diesel units as some beloved examples for Japanese railfans – and ran more peak service to however the trunk lines can handle. But the commute crowding would not relent. Consider the following five major regional lines’ average congestion rate in 1965:

(A criteria set by the Railway Bureau of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, 100% congestion rate is every rider in a train car being able to get a seat, grab a hanging strap or hold onto a bar. 250% is defined as “every time the train sways, my body becomes slanted and can’t move, my hands are immobile”)

The dangerous crowding levels proved highly fatal when a train was involved in an accident. In 1962, a freight train and three consecutive passenger trains on the Joban Line collided, killing 160 passengers and injuring 296 in the Mikawashima Accident. In 1963, two passenger trains collided with a derailed freight train on the Tokaido Line, killing 162 passengers and injuring 120 in the Tsurumi Accident.

With forecasted population growth at nearly the same rate into the late 1960s and 1970s in the Greater Tokyo Area, JNR found itself in an impossible position. It had to plan for a future ridership when current ridership was already suffocating. With car ownership skyrocketing across Japan, JNR was already seeing its near-monopolistic market share in passenger traffic decline in the early 1960s.Nothing short of a radical rebuild of their most reliant infrastructure may be able to rescue them out of this crisis.

Spirits of the five lines of the Commuting Five Directions Operation. A good Internet-age reminder that Japanese railfans and transit fans also appreciate the work of the operation. From top left, clockwise (to best I can): Tohoku Line; Tokaido Line (fused with Yokosuka Line); Sobu Line; Chuo Line; Joban Line. Credit goes to @whitecuizer on Twitter.

The Commuting Five Directions Operation, 1965-1982

In 1965, the Japanese National Railways proposed its Third Five Year Long-Term Plan. In the plan, the Commuting Five Directions Operation served as a centerpiece, providing a roadmap to massively adding capacity on five of its most important regional lines. The operation included various methods to add capacity such as: expanding trackways to quadruple or sextuple tracks; building a new set of tracks reserved entirely for a new rapid line; separating multiple lines running on same track by converting a parallel freight line to a passenger rail line; extending a rail line underground to bypass previous bottlenecks; splitting one train line into two lines, one rapid and one local; and extending the terminus of one train line to provide support for the other.

It would take 17 years in full to be realized, with the last improvement completed on the Joban Line in 1982. Certain projects actually started prior to 1965 but were assimilated into the Commuting Five Directions Operation package to show an united front against current conditions for the five regional lines. The new Tokyo Metro Tozai and Chiyoda lines were already planned out and under construction; several improvements on the Tohoku Line and Chuo Line already passed its approval phase by 1965.

Prior to the launch of the Commuting Five Directions, JNR has taken a more passive approach to improving its regional rail infrastructure. JNR believed then “commuter transportation in large cities should be addressed by the national government or the metropolitan government, and tackle it in relation to housing policy." JNR was then focused on bridging the island nation together via new rail with new technologies; the first Shinkansen which connected Tokyo to Osaka in 1964 served as the shining example of this vision. Despite heavy ridership, JNR had no major priorities set for Tokyo’s regional rail.

That changed with the new JNR President, Reisuke Ishida. Ishida spoke of his revelation of needing action now for regional rail after witnessing packed crowds waiting at Shinjuku and Ikebukuro stations. “I no longer have time to talk about government work or the city work. It would be a big deal if I left it alone…What we have to solve now is the problem of how to deal with this traffic hell of commuting, this problem of how to deal with the overcrowding schedule on the main line, and this problem of how to deal with the safety of transportation in the meantime.”

Budget-wise, JNR internal documents show it spent 313 billion Yen on ground equipment and 70 billion Yen on vehicles in 1965 prices. (716 billion Yen and 114 billion Yen, respectively, in 1995 prices; approximately $6.5 billion and $1 billion in 2022 USD) JNR largely took loans to finance the Commuting Five Directions Operation, similarly to their Shinkansen project.

The Commuting Five Directions Operation:A Breakdown

Author’s note: I have created the simplified hand-drawn before/after pictograms to highlight the various changes the Japanese National Railways invested to complete the Commuting Five Directions Operation. The drawings were inspired by this Japanese explainer video by ViMCooMa Project as the clearest way to demonstrate the infrastructural changes:

Chuo Line

Chuo Line runs west from central Tokyo in a near straight line, connecting to the western Tama areas inside Tokyo. Chuo Line shared parts of its right-of-way with the Chuo-Sobu Line, which runs as a fusion between the Chuo (west) and Sobu (east) lines.

Improvements to help Chuo Line came before 1965, as work was already underway to extend the Chuo-Sobu Line from Nakano 8 kms west, to Mitaka. Double tracks for both lines will run from Mitaka to Ochanomizu Station, just north of central Tokyo. In 1966, the first phase of the extension was completed; in 1969, the full extension was completed. The opening of Tokyo Metro’s Tozai Line, which terminates at Nakano, was opened by then to provide another alternative for commuters avoiding the Chuo Line.

Tohoku Line

Tohoku Line runs north of Tokyo and the full line extends more than 500 kms until its terminus at Morioka, a small city in the north of Honshu Island. The Tokyo regional rail service which run on the Tohoku Line is called Utsonomiya Line.

Previous to the Commuter Five Directions Operation, the Utsonomiya Line and the Keihin-Tohoku Line — a sort of super-charged intercity rail line which connects Saitama, Tokyo and Yokohama’s central stations — ran on the same tracks between Omiya Station in Saitama and Akabane Station in northern Tokyo. There was another set of tracks for freight carry only.

The Utsonomiya Line and Keihin-Tohoku Line received their own pair of tracks in an expansion effort from the Operation. The sextuple tracks allowed for other lines, such as the Takasaki Line and the Shonan-Shinjuku Line (not illustrated) to run trains on the Utsonomiya Line for a segment of their run, adding even more capacity to the benefit of riders on any station on the trunk line.

Joban Line

Joban Line runs northeast from central Tokyo. While the full Joban Line runs 200 kms total until the city of Iwaki in northeast Honshu Island, the Tokyo regional rail ends at Toride, some 37 kms away from Tokyo.

Prior to the Commuter Five Directions Operation, local, medium-distance and rapid express trains all ran on one set of tracks. About 30 kms of new rail tracks were to be added for the Joban Line between Toride and Ayase, just east of Arakawa River (west of Arakawa is Tokyo city proper). The new set of tracks would serve the Joban Line local trains; from Ayase into Tokyo, the newly opened Tokyo Metro Chiyoda Line will help connect.

In 1971, the 24 km long local train tracks from Ayase to Abiko opened. It would take 11 more years, for 6 more kms from Abiko to Toride. It would be the last Commuter Five Directions Operation project to cross the finishing line.

Sobu Line

Prior to the Commuter Five Directions Operations, the Sobu Line was part of the Chuo-Sobu Line where local and rapid express trains ran on the same set of tracks.

JNR determined a Sobu Line which directly connects to Tokyo Station was needed. A 2.3 km-long underground tunnel from Tokyo Station was first constructed to allow a future Sobu Line to enter central Tokyo. The underground tunnel connects to an extra set of tracks for the the new rapid express Sobu Line which runs alongside Chuo-Sobu Line from Ryogoku Station (but does not stop there) eastwards. In 1972, the extra tracks were completed to Tsudanama, west of Chiba, opening the first phase of the rapid Sobu Line. In 1981, the rapid Sobu Line was extended to Chiba.

Relief also came in the form of the Tozai Line, which opened in 1969. Like its Chuo Line counterpart in Nakano in the west, Tozai Line’s easternmost terminus is at Nishi-Funabashi Station. This connection at Nishi-Funabashi provided a new route for Chuo-Sobu Line riders to traverse west-east through central Tokyo through the Tozai Line.

Tokaido/Yokosuka Line

It is hard to underplay the importance of the Tokaido Line to the Japanese rail network. Tokaido Line is the oldest rail line in Japan, and its entirety connects Tokyo to Osaka, the second largest city. With history significance — Tokaido Line runs along an ancient road — the Tokaido Line is also strategically important and high in demand. In the late 1950s, the Tokaido Line alone handled 24% of Japan’s entire passenger rail traffic and 23% of Japan’s freight rail traffic. The first Shinkansen was built along the Tokaido Line to connect Tokyo and Osaka under 2.5 hours.

Within the Greater Tokyo Area, the Tokaido Line was one of two major southbound regional rail lines, along with Yokosuka Line. Prior to the Commuting Five Directions Operation, Tokaido and Yokosuka Lines ran on the same set of tracks from Tokyo to Ofuna, 50 kms south. This severely constrained both high-demand lines to run more trains and carry more passengers.

The Commuting Five Directions Operation required several projects to separate the Tokaido and Yokosuka Lines. First, an underground line was added between Tokyo Station and Shinagawa Station just south of Tokyo for Yokosuka Line in 1976. (Some rapid Sobu Line use this to run express trains south of Tokyo on the Yokosuka Line. In some maps and way finding signages, rapid Sobu Line and Yokosuka Line are shown as a paired line). Second, a segment of the Yokosuka Line after Shinagawa heads away from the Tokaido Line onto a former freight line called the Hinkaku Line; this diversion separates Yokosuka Line entirely from the Tokaido Line between Shinagawa and just north of Yokohama at Tsurumi (where the 1963 fatal accident occurred). This was completed in 1980. The Yokosuka Line then rejoins the Tokaido Line at Tsurumi — but does not stop at the station — and runs parallel with the Tokaido Line in a new set of tracks south through Yokohama and ultimately Ofuna.

Due to the length and the complexity (in needing to rejigger freight lines for this separation), Tokaido and Yokosuka were not separated fully until 1980.

Impact on Congestion

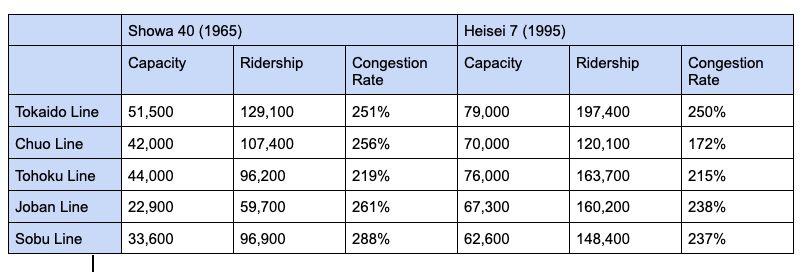

In his 1995 study, Yoshimasa Tadenuma at the Transport Policy Research Institute looked into evaluating how much the Commuting Five Directions Operation impacted commuting capacity and congestion rates during a single peak commute hour. In his study, he displayed this table comparing the five lines’ 1965 conditions to 1995 conditions, a generation after the Operation’s completion.

A few points stand out. One, all but the Chuo Line saw little drops in its congestion rate. For a normal rider, congestion rates on the Joban Line differing from 261% to 238% 30 years later would mean little; it’s still a very crowded train. But perhaps a more esoteric understanding is that the five regional lines were able to absorb the forecasted demand very admirably and efficiently. As its capacity grew substantially (i.e. more trains per hour on the line), ridership kept apace because regional rail remained the most efficient method to get to/from central Tokyo. It is also important to remember this table only reflects the peak commute times, the worst times to be catching a train in Tokyo. While ridership can be highly elastic, the capacity remained mostly fixed to off-peak riders’ benefits.

Tadenuma also produced this table of what congestion rate may be, should population growth and ridership demand in 1995 were held constant but no capacity investments were made.

It is virtually physically impossible to go past 300% congestion rate; that may require gruesome injuries to squeeze enough human bodies to achieve. But they serve as a portal for an alternative Tokyo without the investments: a Tokyo where riders, fed up with being callously stuffed into platforms and trains every workday, give up on their commute rail trip habits and seek alternative ways to get to work. It may be another rail route, or a car, or they leave Tokyo altogether. Imagine a less denser, more car-centric Tokyo. JNR faced a daunting challenge in the 1960s, and signs pointed to this alternative — dare I say, Americanized — Tokyo potentially becoming ascendant. But instead they forged another future for Tokyo, by taking the boldest option available without haste.

“The Young Soldier” and JNR’s troubles

Japanese National Railways President Reisuke Ishida, “The Young Soldier”, waits for his train

While the conditions necessary for the Commuting Five Directions Operation were fully ripe, it’s hard to imagine its current-day yields without the Japanese National Railways president, Reisuke Ishida. Ishida, then 79 years old, was two years into the new job when he announced the operation. After decades of experience running a zaibatsu (conglomerate), Ishida spent all his political capital and know-how to steer a behemoth JNR through a post-Shinkansen era. The Commuting Five Directions Operation would be Ishida’s Shinkansen equivalent.

The President of JNR was one of the most powerful bureaucrats in postwar Japan, and Ishida’s four predecessors resigned in humiliation — or worse. Ishida’s immediate predecessor, Shinji Sogo, was the mastermind in creating the Tokaido Shinkansen. Sogo was forced to resign in 1963 after he was caught hiding and diverting JNR funds to continue funding the Shinkansen, a project which then weathered many doubters and political enemies. It was Ishida — not Sogo, the posthumously acclaimed architect of the Shinkansen — who cut the ribbon for the Shinkansen in 1964; Sogo was not invited to the ceremony.

The first ever JNR President, Sadanori Shimoyama, lasted a month in his job before his body was found dismembered after being hit by a JNR train in Tokyo. The “Shimoyama Incident” remains one of the greatest mysteries in postwar Japan, still capturing Japanese public imagination. Shrouded by patchy details, suspicious biopsy results and a host of possible enemies, Shimoyama’s death motives range from suicide to murder by Communist provocateurs sowing domestic chaos, disgruntled JNR employees who Shimoyama was to lay off en masse forced by the U.S. occupying forces in Japan, or the Americans themselves who disliked Shimoyama’s reticence to their orders. The second and third presidents resigned after massive fatal JNR accidents involving a 1951 train fire in Yokohama killing 106 people in broad daylight and a 1955 ferry crash which killed 168 people, most of whom were children en route to a field trip, respectively.

Ishida was 77 years old when he was picked by Prime Minister Hayato Ikeda for the JNR job in 1963. He exuded a cool, frank demeanor with a penchant for memorable quotes. When asked by journalists if his age would be a hindrance to his job, Ishida said he “felt like a young soldier.” After a lifetime working for the conglomerate Mitsui & Co., Ishida boasted in another press conference “if I can’t do this, then who can?”

In an address to the Japanese Diet (the national parliamentary body), Ishida introduced himself by saying, "Although I'm frank and informal in my expressions on many occasions, I don't think my ideas are undignified."

Ishida did not have an ignominious exit like his four predecessors; he left in 1969 and died in 1978 at the age of 92. At Ishida’s request, only a handful of JNR employees were allowed to show up to his funeral; some were off-duty employees at his local station he commuted regularly. His widow refused posthumous honors from the government for Ishida, continuing Ishida’s resistance to them when he was alive as he did not want to be seen as “a monkey decorated with medals.”

However, Ishida also put in motion a beginning of the end for his beloved JNR. After many years of profit, JNR sunk into the red for the first time in 1964, his second year as president. JNR never left the deficits since, and debts incurred from the Shinkansen project and the Commuting Five Directions Operation catalyzed a debt crisis in JNR by the 1970s. Ultimately, in the 1980s, the Japanese government intervened to resolve the debt-ridden JNR. By 1987, JNR was no longer alive, and its infrastructure and services were divided into regional and privatized Japanese Railways (JR) companies.

Final Thoughts Before Intermission

This deep dive into the Commuting Five Directions Operation was a labor of love and labor to find some hard answers. Despite witnessing countless conversations about how Japan — and especially Tokyo — has incredible passenger rail for the world to envy, very few concrete answers were given about HOW they infrastructurally got there. This report is an attempt to answer my own burning questions.

After writing this post, I now believe too many discussions on what makes Japanese rail world-class (at least in the English-speaking internet) miss both the tree and the forest: it misses the great hardships Japan overcame to become a world leader in rail and the fundamental transformations it underwent to reach the current state. Japan for the first 20-30 years after the war had terrible passenger rail in terms of safety and convenience. From the 1947 Hachiko Line derailment (186 dead), the 1951 Sakuragicho train fire (106 dead), 1962 Mikawashima accident (160 dead) and 1963 Tsurumi accident (162 dead), among many, many other highly fatal rail accidents at the time, Japan’s climb to the mountaintop was littered with horrendous accidents from infrastructural neglect and decay, a symptom of a country reeling from a total war loss and destitution unlike anything North America has seen in modern times.

Projects like the Commuting Five Directions Operation were major projects to not only add capacity to congested train lines but to pave the way for further modernization in the network. With more tracks to run trains, Tokyo was able to develop and open multiple lines such as the Shonan-Shinjuku line which runs entirely on select parts of existent trunk lines (Tohoku and Yokosuka/Tokaido are some partners who share tracks). It is this flexibility thanks to added capacity which gives Tokyo, and Japan by large, the steel to build world-class transit atop world-class transit.

In Part II, I will review the legacy of the Commuting Five Directions Operation. I will look at whether it solved congestion (as explained above, sort of yes), accommodated for rising ridership (as explained above, yes), cut travel time (spoiler: yes), was worth the billions of Yen as investments (spoiler: yes) and whether the Greater Tokyo Area is in better shape for it (spoiler: yes). In a show of potential bravado, I may even go one step further to argue the privatized and very profitable JR East Company, which run all five regional lines, are merely reaping the fruits of its public predecessor sowed decades before its dissolution.

Until Part II, whenever that is published, my hope is that the Five Commuting Directions Operation enter into parlance of the innumerable discourse around what makes Japanese rail so fantastic. I believe this project should be discussed as much as the Shinkansen perhaps for one simple reason: it feels far more imitable here in North America to focus on the basics to transform passenger rail than building brand new bullet train lines.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/yNhLbY7

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.