As most of you know, I just took three days completely offline so that I could discover what would be difficult about it.

I have so much to say about that three days, and first thing I would like to report is that there was almost nothing difficult about it.

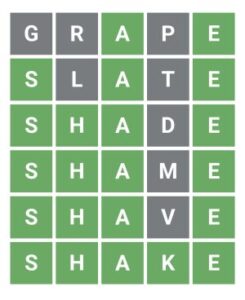

To my surprise, I didn’t crave the internet at all. I wasn’t dying to check email, judge people on Twitter, or figure out the day’s Wordle. Instead I did my daily work — very little of which requires the internet, I discovered — and simply lived life in the physical world.

This simplicity was disorienting in a way. Many times a day I would finish whatever activity I was doing, and realize there was nothing to do but consciously choose another activity and then do that. This is how I made my first bombshell discovery: I take out my phone every time I finish doing basically anything, knowing there will be new emails or mentions or some other dopaminergic prize to collect. I have been inserting an open-ended period of pointless dithering after every intentional task.

With my phone parked in a cardboard pouch taped to my kitchen wall, this ritual was unavailable, so I again and again found myself hitting a kind of intentionless vacuum, where nothing would happen until I consciously formed a new intention to get on with the day, in a way of my choosing. I can’t convey the strangeness of this feeling — it was like repeatedly discovering that I had misplaced my cane again, only to remember I can walk just fine.

This new mode of living came with another alien sensation: that of having tons of time. The days were long and waiting for me to fill them, like so many empty moving trucks. There was nothing to do but do things.

My attention span did improve noticeably. By the second day, both reading and meditation were far less effortful than they’ve been for the past few years, and I didn’t have to mentally “roll up my sleeves” to begin doing them. This was thrilling, and in hindsight should not be surprising –- my phone habits could only have trained my attention to branch constantly, seeking gratification on demand, and instantly-Googled answers to every question occurring to the mind.

Life seemed quieter — calm and simple and local to the room I was in, like it does after a spa visit or meditation retreat. Even the experience of passive entertainment became simpler and less stressful. If I put on a movie, I would simply watch the movie until it was either over or it was clear I’d rather do something else. Then I would go and do something else, rather than drift away into my phone, where I would browse my WhatsApp chats, skip through people’s boring Instagram stories, or look up how old the actors were during filming.

And thus I learned what was probably the most important lesson of the three days: without the internet, there was no way to collapse into the mushy, nihilistic state of semi-doing. There was just doing. I could always choose what to do, but not not to do.

Checking the Weather

Throughout the three days I wrote on a clipboard things I later wanted to do or look up online. There were surprisingly few instances when I found I needed certain information right away. A few times while running errands I flipped on mobile data to look up an address, then flipped it off, email unchecked.

My mom and I had discussed vague plans to go for a walk, and I wanted to check the forecast before proposing a time and place. I quickly realized I didn’t have access to basic weather information.

I was proud of my elegant, old-fashioned solution. I called and asked my mom if she had seen the forecast. She had, and she told me what it was.

Normally, by that time of day (noonish), I would have checked the weather 17 times or so already, all but one of them a pointless reflexive tic.

The Return of “The World Out There”

The larger goal that inspired this experiment is to figure out how to “put the internet back into a box in the basement” — that is, make it a contained tool I use only intentionally and sparingly. I did achieve this to some degree, and with that came many nostalgic feelings of what my mind used to be like.

The most important of these feelings was a distinct sense that there’s a whole world out there. Not out there on the internet, but out there over the horizon. Out there in this same world are jungle cats, opera houses, subterranean hideouts, breakdancing circles, riverside tire swings, and old women playing mahjong. There are desert caravans and bullet trains and foggy valleys and kangaroos, and I can one day visit some of these things or maybe just read about them.

Reconnecting with this feeling, which I used to have all the time, made me realize what exactly has happened to the internet over the past decade. It used to function as a magic window onto our vast and colorful world, and that made it very exciting to look through. Today, my internet experience is so uniformly shaped by the big platforms that I have little sense that the world it’s showing me is vast or interesting at all. It shows me the same expected things every day – the same partisan opinions, the same jokes, the same forms of recreational scrolling and tapping, the same tone and feeling. To go on the internet today –- at least without very specific intentions — is to swallow another large bucket of the same tepid punch you have every day.

This is not because we’ve looked out the magic window so much that we’ve seen everything by now, it’s because the big online platforms have a certain business model, and that model entails a very uniform experience for its users, characterized by familiar memes, a poisonous culture war, and approval points in the form of hearts and stars. The typical online experience has become a very small and limited thing –- something the world itself has never been.

After spending only a few days away from this experience, the world feels more like a vast and colorful thing again. Everything that hints at the real world out there – what I read in books, what my friends tell me about their lives, what I see when I go places in my city – makes the world seem like it’s bursting with things I’ve never known or seen, which of course it is and always was.

What Happened When I Went Online Again

The first morning I was allowed to use the internet again, I waited until late morning. I already knew I never wanted to go back to all-day reflexive internet use.

My first stop was meant to be harmless enough – Wordle, the trendy guess-the-word game that takes about three minutes and only lets you play it once a day. I felt the usual excitement when those first green-boxed letters appeared, but there was also a background unease to the whole thing. It felt like my life, which had been so vital and interesting lately, was on pause until I got the puzzle. The simple loop of intending and doing I had enjoyed for the past three days was now on hold, if only for a few minutes, until I figured out a five-letter word with “Y” as its second letter. This delay felt not just unnecessary, but borderline nihilistic, and I was relieved to be done with it. In my notes I described it as a “mild purgatory” — like being stuck in human flypaper.

Then I went on Instagram, and had a similar experience. There was some initial gratification at seeing what my friends had been up to. Smiling faces. Cakes. Dogs. Toddlers. Mostly good feelings. But I also had that feeling that I was again delaying the living of life until I completed a three-minute ritual with marginal rewards and no clear purpose. Pictures had to be scrolled through, liked, tapped. Political opinions had to be scowled at, affirmed, or ignored.

I did it quickly because I had many more rituals to complete afterward – Gmail, Twitter, fantasy hockey, WhatsApp banter, chess games in progress. Aside from a few necessary emails and messages from friends, none of them seemed to justify the short but complete stoppage of living and doing that they demanded.

How I Want to Use the Internet

In the days since the experiment, I’ve found myself thumbing through my internet rituals out of habit, and unfortunately the absurdity of them doesn’t hit me as strongly as on that first day back.

I realize now that putting the internet back into a box in the basement in a lasting way will require explicit boundaries, and I will have to practice observing them.

Here’s a list of proposed rules I typed out after that first disorienting day back. These are the boundaries I’d like to observe, given my own routines. If the idea of putting the internet back into a box appeals to you, you might want to try something similar, adjusting for your own habits.

1. By default, data and Wi-Fi on my devices is off, and the laptop is closed. Calls and texts are accepted.

2. By default, the phone is out of arm’s reach (in its wall-mounted holster in the kitchen, if possible)

3. By default, I don’t use the internet before 11am

4. By default, Saturday and Sunday are offline days

5. By default, one or two weekdays are offline days (which ones depend on the week)

6. By default, before turning on data or Wi-Fi, I list on a sticky note what I’m going to do online

7. By default, don’t choose an online activity when an offline one will do

8. By default, avoid taking on hobbies that require regular internet use

9. When you notice you’re ignoring these rules, close the laptop and put the phone away, and choose an offline activity to do for a while*

The “by default” part is important. This list represents the way I’d like to use the internet most of the time. The rules won’t make sense in every situation, but I’d like to follow them unless I have a clear reason not to.

These rules won’t be right for everyone – I don’t tend to overdo text messages, for example, so I don’t feel a need to limit them – but they could be a starting point for your own boundaries if you want to make the internet a smaller thing in your life.

Living Without a Ripcord

Perhaps the fundamental lesson of this experiment was that the vast majority of my internet use simply serves to delay the rest of my life. It’s a way of momentarily escaping the responsibility of using my life intentionally — a ripcord I apparently want to pull constantly.

It was a relief to discover that living without this ripcord quickly came to feel very natural and familiar. It’s as though I used to live this way all the time.

***

*This is where a Cupboard Sheet comes in handy.

Photos by Stephane Yaich, David Cain, CardMapr, Meg Jerrard, Wesley Hilario, Qi Bin, and David Cain

More Raptitude?

Raptitude is now on Patreon. It's an easy way to help keep this site ad-free. In exchange for your support, you get access to extra posts and other goodies. Join a growing community of patrons. [See what it's all about]from Hacker News https://ift.tt/Dfk2IdL

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.