My NixOS Desktop Flow

Before I built my current desktop, I had been using a 2013 Mac Pro for at least 7 years. This machine has seen me through living in a few cities (Bellevue, Mountain View and Montreal), but it was starting to show its age. Its 12 core Xeon is really no slouch (scoring about 5 minutes in my “compile the linux kernel” test), but with Intel security patches it was starting to get slower and slower as time went on.

So in March (just before the situation started) I ordered the parts for my new tower and built my current desktop machine. From the start, I wanted it to run Linux and have 64 GB of ram, mostly so I could write and test programs without having to worry about ram exhaustion.

When the parts were almost in, I had decided to really start digging into NixOS. Friends on IRC and Discord had been trying to get me to use it for years, and I was really impressed with a simple setup that I had in a virtual machine. So I decided to jump head-first down that rabbit hole, and I’m honestly really glad I did.

NixOS is built on a more functional approach to package management called Nix. Parts of the configuration can be easily broken off into modules that can be reused across machines in a deployment. If Ansible or other tools like it let you customize an existing Linux distribution to meet your needs, NixOS allows you to craft your own Linux distribution around your needs.

Unfortunately, the Nix and NixOS documentation is a bit more dense than most other Linux programs/distributions are, and it’s a bit easy to get lost in it. I’m going to attempt to explain a lot of the guiding principles behind Nix and NixOS and how they fit into how I use NixOS on my desktop.

What is a Package?

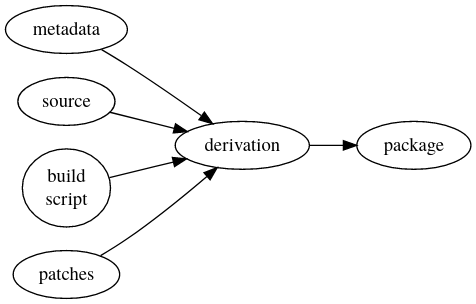

Earlier, I mentioned that Nix is a functional package manager. This means that Nix views packages as a combination of inputs to get an output:

This is how most package managers work (even things like Windows installer files), but Nix goes a step further by disallowing package builds to access the internet. This allows Nix packages to be a lot more reproducible; meaning if you have the same inputs (source code, build script and patches) you should always get the same output byte-for-byte every time you build the same package at the same version.

A Simple Package

Let’s consider a simple example, my gruvbox-inspired CSS file’s default.nix file’:

{ pkgs ? import <nixpkgs> { } }: pkgs.stdenv.mkDerivation { pname = "gruvbox-css"; version = "latest"; src = ./.; phases = "installPhase"; installPhase = '' mkdir -p $out cp -rf $src/gruvbox.css $out/gruvbox.css ''; } This creates a package named gruvbox-css with the version latest. Let’s break this down its default.nix line by line:

{ pkgs ? import <nixpkgs> { } }: This creates a function that either takes in the pkgs object or tells Nix to import the standard package library nixpkgs as pkgs. nixpkgs includes a lot of utilities like a standard packaging environment, special builders for things like snaps and Docker images as well as one of the largest package sets out there.

pkgs.stdenv.mkDerivation { # ... } This runs the stdenv.mkDerivation function with some arguments in an object. The “standard environment” comes with tools like GCC, bash, coreutils, find, sed, grep, awk, tar, make, patch and all of the major compression tools. This means that our package builds can build C/C++ programs, copy files to the output, and extract downloaded source files by default. You can add other inputs to this environment if you need to, but for now it works as-is.

Let’s specify the name and version of this package:

pname = "gruvbox-css"; version = "latest"; pname stands for “package name”. It is combined with the version to create the resulting package name. In this case it would be gruvbox-css-latest.

Let’s tell Nix how to build this package:

src = ./.; phases = "installPhase"; installPhase = '' mkdir -p $out cp -rf $src/gruvbox.css $out/gruvbox.css ''; The src attribute tells Nix where the source code of the package is stored. Sometimes this can be a URL to a compressed archive on the internet, sometimes it can be a git repo, but for now it’s the current working directory ./..

This is a CSS file, it doesn’t make sense to have to build these, so we skip the build phase and tell Nix to directly install the package to its output folder:

mkdir -p $out cp -rf $src/gruvbox.css $out/gruvbox.css This two-liner shell script creates the output directory (usually exposed as $out) and then copies gruvbox.css into it. When we run this through Nix withnix-build, we get output that looks something like this:

$ nix-build ./default.nix these derivations will be built: /nix/store/c99n4ixraigf4jb0jfjxbkzicd79scpj-gruvbox-css.drv building '/nix/store/c99n4ixraigf4jb0jfjxbkzicd79scpj-gruvbox-css.drv'... installing /nix/store/ng5qnhwyrk9zaidjv00arhx787r0412s-gruvbox-css And /nix/store/ng5qnhwyrk9zaidjv00arhx787r0412s-gruvbox-css is the output package. Looking at its contents with ls, we see this:

$ ls /nix/store/ng5qnhwyrk9zaidjv00arhx787r0412s-gruvbox-css gruvbox.css A More Complicated Package

For a more complicated package, let’s look at the build directions of the website you are reading right now:

{ pkgs ? import (import ./nix/sources.nix).nixpkgs }: with pkgs; assert lib.versionAtLeast go.version "1.13"; buildGoPackage rec { pname = "christinewebsite"; version = "latest"; goPackagePath = "christine.website"; src = ./.; goDeps = ./nix/deps.nix; allowGoReference = false; preBuild = '' export CGO_ENABLED=0 buildFlagsArray+=(-pkgdir "$TMPDIR") ''; postInstall = '' cp -rf $src/blog $bin/blog cp -rf $src/css $bin/css cp -rf $src/gallery $bin/gallery cp -rf $src/signalboost.dhall $bin/signalboost.dhall cp -rf $src/static $bin/static cp -rf $src/talks $bin/talks cp -rf $src/templates $bin/templates ''; } Breaking it down, we see some similarities to the gruvbox-css package from above, but there’s a few more interesting lines I want to point out:

{ pkgs ? import (import ./nix/sources.nix).nixpkgs }: My website uses a pinned or fixed version of nixpkgs. This allows my website’s deployment to be stable even if nixpkgs changes something that could cause it to break.

with pkgs; With expressions are one of the more interesting parts of Nix. Essentially, they let you say “everything in this object should be put into scope”. So if you have an expression that does this:

let foo = { ponies = "awesome"; }; in with foo; "ponies are ${ponies}!" You get the result "ponies are awesome!". I use with pkgs here to use things directly from nixpkgs without having to say pkgs. in front of a lot of things.

assert lib.versionAtLeast go.version "1.13"; This line will make the build fail if Nix is using any Go version less than 1.13. I’m pretty sure my website’s code could function on older versions of Go, but the runtime improvements are important to it, so let’s fail loudly just in case.

buildGoPackage { # ... } buildGoPackage builds a Go package into a Nix package. It takes in the Go package path, list of dependencies and if the resulting package is allowed to depend on the Go compiler or not.

It will then compile the Go program (and all of its dependencies) into a binary and put that in the resulting package. This website is more than just the source code, it’s also got assets like CSS files and the image earlier in the post. Those files are copied in the postInstall phase:

postInstall = '' cp -rf $src/blog $bin/blog cp -rf $src/css $bin/css cp -rf $src/gallery $bin/gallery cp -rf $src/signalboost.dhall $bin/signalboost.dhall cp -rf $src/static $bin/static cp -rf $src/talks $bin/talks cp -rf $src/templates $bin/templates ''; This results in all of the files that my website needs to run existing in the right places.

Other Packages

For more kinds of packages that you can build, see the Languages and Frameworks chapter of the nixpkgs documentation.

If your favorite language isn’t shown there, you can make your own build script and do it more manually. See here for more information on how to do that.

nix-env And Friends

Building your own packages is nice and all, but what about using packages defined in nixpkgs? Nix includes a few tools that help you find, install, upgrade and remove packages as well as nix-build to build new ones.

nix search

When looking for a package to install, use $ nix search name to see if it’s already packaged. For example, let’s look for graphviz, a popular diagramming software:

$ nix search graphviz * nixos.graphviz (graphviz) Graph visualization tools * nixos.graphviz-nox (graphviz) Graph visualization tools * nixos.graphviz_2_32 (graphviz) Graph visualization tools There are several results here! These are different because sometimes you may want some features of graphviz, but not all of them. For example, a server installation of graphviz wouldn’t need X windows support.

The first line of the output is the attribute. This is the attribute that the package is imported to inside nixpkgs. This allows multiple packages in different contexts to exist in nixpkgs at the same time, for example with python 2 and python 3 versions of a library.

The second line is a description of the package from its metadata section.

The nix tool allows you to do a lot more than just this, but for now this is the most important thing.

nix-env -i

nix-env is a rather big tool that does a lot of things (similar to pacman in Arch Linux), so I’m going to break things down into separate sections.

Let’s pick an instance graphviz from before and install it using nix-env:

$ nix-env -iA nixos.graphviz installing 'graphviz-2.42.2' these paths will be fetched (5.00 MiB download, 13.74 MiB unpacked): /nix/store/980jk7qbcfrlnx8jsmdx92q96wsai8mx-gts-0.7.6 /nix/store/fij1p8f0yjpv35n342ii9pwfahj8rlbb-graphviz-2.42.2 /nix/store/jy35xihlnb3az0vdksyg9rd2f38q2c01-libdevil-1.7.8 /nix/store/s895dnwlprwpfp75pzq70qzfdn8mwfzc-lcms-1.19 copying path '/nix/store/980jk7qbcfrlnx8jsmdx92q96wsai8mx-gts-0.7.6' from 'https://cache.nixos.org'... copying path '/nix/store/s895dnwlprwpfp75pzq70qzfdn8mwfzc-lcms-1.19' from 'https://cache.nixos.org'... copying path '/nix/store/jy35xihlnb3az0vdksyg9rd2f38q2c01-libdevil-1.7.8' from 'https://cache.nixos.org'... copying path '/nix/store/fij1p8f0yjpv35n342ii9pwfahj8rlbb-graphviz-2.42.2' from 'https://cache.nixos.org'... building '/nix/store/r4fqdwpicqjpa97biis1jlxzb4ywi92b-user-environment.drv'... created 664 symlinks in user environment And now let’s see where the dot tool from graphviz is installed to:

$ which dot /home/cadey/.nix-profile/bin/dot $ readlink /home/cadey/.nix-profile/bin/dot /nix/store/fij1p8f0yjpv35n342ii9pwfahj8rlbb-graphviz-2.42.2/bin/dot This lets you install tools into the system-level Nix store without affecting other user’s environments, even if they depend on a different version of graphviz.

nix-env -e

nix-env -e lets you uninstall packages installed with nix-env -i. Let’s uninstall graphviz:

$ nix-env -e graphviz Now the dot tool will be gone from your shell:

$ which dot which: no dot in (/run/wrappers/bin:/home/cadey/.nix-profile/bin:/etc/profiles/per-user/cadey/bin:/nix/var/nix/profiles/default/bin:/run/current-system/sw/bin) And it’s like graphviz was never installed.

Notice that these package management commands are done at the user level because they are only affecting the currently logged-in user. This allows users to install their own editors or other tools without having to get admins involved.

Adding up to NixOS

NixOS builds on top of Nix and its command line tools to make an entire Linux distribution that can be perfectly crafted to your needs. NixOS machines are configured using a configuration.nix file that contains the following kinds of settings:

- packages installed to the system

- user accounts on the system

- allowed SSH public keys for users on the system

- services activated on the system

- configuration for services on the system

- magic unix flags like the number of allowed file descriptors per process

- what drives to mount where

- network configuration

- ACME certificates

At a high level, machines are configured by setting options like this:

# basic-lxc-image.nix { config, pkgs, ... }: { networking.hostName = "example-for-blog"; environment.systemPackages = with pkgs; [ wget vim ]; } This would specify a simple NixOS machine with the hostname example-for-blog and with wget and vim installed. This is nowhere near enough to boot an entire system, but is good enough for describing the base layout of a basic LXC image.

For a more complete example of NixOS configurations, see here or repositories on this handy NixOS wiki page.

The main configuration.nix file (usually at /etc/nixos/configuration.nix) can also import other NixOS modules using the imports attribute:

# better-vm.nix { config, pkgs, ... }: { imports = [ ./basic-lxc-image.nix ]; networking.hostName = "better-vm"; services.nginx.enable = true; } And the better-vm.nix file would describe a machine with the hostname better-vm that has wget and vim installed, but is also running nginx with its default configuration.

Internally, every one of these options will be fed into auto-generated Nix packages that will describe the system configuration bit by bit.

nixos-rebuild

One of the handy features about Nix is that every package exists in its own part of the Nix store. This allows you to leave the older versions of a package laying around so you can roll back to them if you need to. nixos-rebuild is the tool that helps you commit configuration changes to the system as well as roll them back.

If you want to upgrade your entire system:

$ sudo nixos-rebuild switch --upgrade This tells nixos-rebuild to upgrade the package channels, use those to create a new base system description, switch the running system to it and start/restart/stop any services that were added/upgraded/removed during the upgrade. Every time you rebuild the configuration, you create a new “generation” of configuration that you can roll back to just as easily:

$ sudo nixos-rebuild switch --rollback Garbage Collection

As upgrades happen and old generations pile up, this may end up taking up a lot of unwanted disk (and boot menu) space. To free up this space, you can use nix-collect-garbage:

$ sudo nix-collect-garbage < cleans up packages not referenced by anything > $ sudo nix-collect-garbage -d < deletes old generations and then cleans up packages not referenced by anything > The latter is a fairly powerful command and can wipe out older system states. Only run this if you are sure you don’t want to go back to an older setup.

How I Use It

Each of these things builds on top of eachother to make the base platform that I built my desktop environment on. I have the configuration for my shell, emacs, my window manager and just about every program I use on a regular basis defined in their own NixOS modules so I can pick and choose things for new machines.

When I want to change part of my config, I edit the files responsible for that part of the config and then rebuild the system to test it. If things work properly, I commit those changes and then continue using the system like normal.

This is a little bit more work in the short term, but as a result I get a setup that is easier to recreate on more machines in the future. It took me a half hour or so to get the configuration for zathura right, but now I have a zathura module that lets me get exactly the setup I want every time.

TL;DR

Nix and NixOS ruined me. It’s hard to go back.

This article was posted on 2020 M4 25. Facts and circumstances may have changed since publication. Please contact me before jumping to conclusions if something seems wrong or unclear.

Series: howto

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2yFrqGC

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.