The recipes and instructions for the making of parchment that survive from the premodern world, while relatively few in number, are quite diverse in the sensibilities they bring to bear on the enterprise they describe. Paleographers and historians of the book have often characterized these instructions as detailed and pragmatic. As modern-day makers who have tried them will be the first to say, however, such instructions can be surprisingly unhelpful when it comes to the specific hands-on elements of the craft. While they might prescribe a bath of water and lime for the flayed hides, for instance, they rarely specify even approximate proportions of each and provide little detailed information about the proper techniques for stretching, scraping, and finishing the rendered skins; what detail they do convey will often be incomprehensible to modern scholars and makers. Most of the scattered recipes and directions found in medieval sources should be regarded less as specialized instructions than as schematic formulas, their aim more to describe than to teach the craft.

This makes them no less relevant as testaments to the assumptions and cultural sensibilities with which the lineaments and hands-on technicalities of this craft work are described. Even the earliest examples contain enough technical information to give a good sense of certain elements of the practice and often loving attunement to detail, as in a recipe or set of guidelines in Coptic compiled in a papyrus codex of the sixth or seventh century. The surviving portion touches mainly on the finishing of the skins, which the anonymous artisan sees in terms of their texture, contour, and tactile quality: “Then you shall wipe it and write on it…When you see that it is shriveled you shall polish it and write on it…If it be one that is all in wrinkles…If it be one that has a corroded skin [ouamshaar], you shall scrape it well with the hard pumice and write on it with a fine reed…If it be one that is sticky, you shall pumice it with the soft sort and shall not wipe it at all.” The term translated here as “corroded skin,” ouamshaar, is a Coptic compound formed from ouam (a verbal adjective meaning “eater,” from the verb ouōm, “to eat”) and shaar, “skin.” A “skineater,” then, is the organic agent responsible for corroding the surface of the membrane. Though written down on papyrus, the fragmentary treatise addresses its careful scrutiny to the already widespread medium of skin.

Another early set of guidelines occurs in a Latin miscellany containing a number of practical treatises, recipes, and formulas for various artisanal usages. Ad faciendas cartas de pellibus caprinis, written on one side of a folio in a twelfth-century German manuscript, provides a rough schematic guide to the processes of soaking, liming, dehairing, and scraping necessary to the making of the commodity:

To make parchment from the skins of goats, as is done in Bologna, take goat skins, and place them in water for a day and a night, then take them out and wash them until the water has cleared. Then take a new vessel, and put in it aged lime and water, and mix them thoroughly so the water is thickened. Now the skins should be placed within, folded on the flesh side. Then stir this with a rod two or three times a day. And let the tub sit thus for eight days, in winter for twice as many. After this the hides must be taken out and dehaired.

The writer prescribes additional days of soaking and rinsing; then “the skins must be taken out and suspended by cords and placed in a circular frame; and then they must be prepared with a keenly sharpened knife.” The last phrase is indicative of the vagueness of most such instructions: any old keenly sharpened knife will do, it seems. But the formula has nothing to say about the most demanding and precarious part of the process: the actual technique for scraping the hide to remove the remaining flesh. The recipe concludes with similarly vague instructions for pumicing the surface and tightening the frame cords to give the parchment its permanent form.

Other recipes for making parchment are more stylized, sacrificing technical specificity for literary license or artful paradox. One example comes to us in the form of a Latin poem from the thirteenth century. The author, the Zurich rector Conrad of Mure, composed the stylized recipe for his De naturis animalium (c. 1270), a metrical compendium of practical knowledge, wisdom, and folklore concerning animals.

on skin, how a page is made from it

The skin of a calf is flayed and deposited in water.

Lime is added, to gnaw away everything rough,

To clean it well, and to remove the hairs.

A circular frame is fashioned, on which the hide is stretched.

It is placed in the sun, so that moisture may be driven out.

Now comes a sharp knife; it rips out flesh and hairs;

It renders the skin fine and pleasing.

The subsequent lines go on to detail the preparation of the scraped and dried calfskin with pumice, chalk, and rulings. The poem describes the parchment-making process in technically vague terms, though what comes across is the figurative brutality of the operation. The knife “rips out” hair and extraneous flesh from its surface; the skin is drowned in acid, then stretched on a frame; and even lime is an aggressive agent that exiles moisture through the acidic action of the calx upon the flesh. The poem closes with a moralizing couplet that plays on the commonplace medieval association of flesh and page: “Skin from flesh, flesh from skin removed: You, too, must withdraw your carnal lust from the flesh.”

Formulas for the making and treatment of parchment often give practical tips for the removal of grease or stains, with the use of powdered quicklime, wood ash, or animal bones; and the effacing or erasure of writing, for which one Italian text of the fifteenth century prescribes orange juice. A set of fifteenth-century guidelines in Middle English provides instructions on how to “done awey what is wreten in Velyn or Parchement withowte any Pomyce”—that is, how to erase words from vellum and parchment without the use of a pumice stone, a common tool for finishing parchment sheets: “Take the juice of rew and of nettle, in March, April, or May, and mix it with cheese, the milk of a cow or of a sheep, add dry lime, mix them well together, and make a loaf, and dry it in the sun, and make powder out of it.” The powder must then be cast on the letters once they are moistened with saliva or water; after that, a quick scratch with the fingernail is all that is required to “done awey the lettres.” “This medicine,” the writer avows, “when made with the cheese or milk of a cow, is good for vellum, and [with the cheese or milk] of a sheep, good for parchment”—implying (quite charmingly) that the species derivation of the cheese or milk will determine the effectiveness of the erasure.

The surviving recipes for parchment making in writings from the Christian tradition tend to steer clear of intra-craft controversy. There is little or no disagreement in these formulas about the proper way of going about the business of rendering acceptable sheets from slaughtered beasts, and they rarely acknowledge the existence of earlier discussions of the subject. The same cannot be said for the numerous early treatments of parchment making in the Jewish tradition, which provide a sharp contrast to the often vague and morally neutral discussions of the process in gentile sources. Rabbinic authorities are often quite frank about regional and sectarian biases that differentiate one custom of parchment craft from another, even to the extent of investigating the accuracy of each other’s claims.

A fascinating example of such controversy occurs in medieval and early modern discussions of so-called split parchment. The twelfth-century philosopher and theologian Moses Maimonides has this to say on the matter of parchment made from hides that have been split:

If, after removing the hair, the hide had been split through its thickness into two layers…so as to make of it two skins, one thin, namely, that which had been next to the hair; the other thick, namely, that which had been next to the flesh…the layer which had been next to the hair is called klaf, and the one which had been next to the flesh is called dukhsustos.

Maimonides takes it for granted that artisans regularly split hides in two, creating discrete membranes of distinct thicknesses, textures, and qualities, all of which impact their suitability for one kind of writing or another. Certain Talmudic discussions of split skins similarly assume technological knowhow among parchment makers sufficient to divide animal hides by hand and render the separate layers of klaf and dukhsustos.

Such evident confidence in the theological literature, though, was very much misplaced. We get a much more skeptical note on the feasibility of splitting parchment in the writings of Benjamin Mussafia (1606-1675), a Kabbalist, philologist, and court physician to the Danish king Christian IV during the 1640s. Mussafia was also an encyclopedist, producing a compendium of Talmudic knowledge, the Musaf he’Aruk, published in 1655 following his move to Amsterdam (and never translated). Mussafia’s long entry on parchment in the Aruk ranges over a number of technical and cultural aspects of the medium, including the matter of splitting skins, on which he actually consults with local parchment makers in his adopted city. Here he is commenting on the technical meaning of the term dukhsustos:

The word in Greek means an animal skin which has been prepared on both sides. The understanding the legal authorities have of this word is especially difficult for me. Firstly, we don’t find that animal skin is actually split into two parts. Indeed, I asked numerous skinworkers about this, but to them I seemed to be joking. They told me that if they had the ability to do such a thing, they would double or quadruple their profits by making two skins out of one, or two thin skins out of one thick one. Secondly, the matter is so difficult that, given that it is preferable to write a mezuzah on dukhsustos, none of the rabbis make pains to have dukhsustos available to them! Far be it from me to dispute the words of the legal authorities—I am only trying to practice my [academic] skill…Whoever told Rabbenu Tam that dukhsustos means flesh in Greek lied to him.

The passage hints at the often unspoken tension between learned theological authority and hands-on craft experience. Rather than settling for the received wisdom of the commentary tradition or even relying on his own theological expertise, Mussafia turns to local makers (most of them probably gentiles) with an everyday knowledge of the parchment craft. As these artisans disdainfully inform him, the dividing of skins in the way implied by the Talmud is a practical impossibility, despite intriguing evidence of the practice in earlier rabbinic sources. As in Mussafia’s day, the subject of split skins remains a matter of some controversy among scholars and makers alike.

A similar reverence for craft knowledge informs the wide-ranging entry on parchemin included in the Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonn, des sciences, des arts et des métiers, par une Société de Gens de lettres, the great compendium of Enlightenment knowledge published between 1751 and 1772 and overseen by Denis Diderot and Jean Le Rond d’Alembert—though the through-reader of the Encyclopédie will encounter the parchment entry several volumes and years after encountering the long entry on the Quran. Here the encyclopedists tell an origin story for Islam’s holy book:

But the Muslims believed, as an article of faith, that their Prophet, who they say was a simple and unlettered man, put nothing of his own into this book, that he received it from God through the ministering of the Angel Gabriel, written on a parchment made of the skin of the ram that Abraham sacrificed in place of his son Isaac, and that it was communicated to him only gradually, verse by verse in different times and in different places, over the course of twenty-three years. Thanks to these interruptions they claim to justify the confusion that reigns throughout the work, a confusion that it is impossible to clarify, that their most able doctors have worked vainly upon, for Muhammad, or if you prefer, his copyist, had gathered pell-mell all these supposed revelations, and so it was no longer possible to find in what order they had been sent from Heaven.

The medium of the Quran, in this account, is the skin of the sacrificed ram, the animal that Abraham found entangled in the bush and slaughtered in place of his son. The ram’s parchment carries the faulty and confused text of the work, supposedly bungled by years of delay and interruption in its transmission. The peculiar legend was repeated in numerous encyclopedias and handbooks of practical knowledge throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and on both sides of the Atlantic. Though its specific source is unknown, the legend bears a close resemblance to a medieval Jewish legend about the origin of the Zohar and may have resulted from a confusion in the early modern period between the two Abrahamic texts and traditions.

The author of the parchemin entry in the Encyclopédie can be identified as Joseph Jérôme Le Français de Lalande, who in 1762 released his own Art de faire le parchemin. This exhaustive study of the craft was published as one of a series of books from the royal Académie des Sciences on various technical trades (Lalande also authored the volume on the art and history of paper making). Lalande’s redaction in the Encyclopédie begins with a skeptical account of the long history of the medium since the ancient world. The technology of parchment was only perfected in the modern era, or so Lalande claims: the entry describes a thriving contemporary international trade in parchment between England, the Low Countries, Spain, and Portugal, making little mention of the medieval history of the medium. The entry includes a detail-oriented description of the parchment-making process, evoking the sight of skins soaking in a river and describing the process of stretching the wet hides on a frame before their drying and scraping, then their bundling for sale and delivery in packets of thirty-six skins. The entry emphasizes the brute force required to scrape skins into the correct thinness, though also the delicacy and lack of damage to the surface at the hands of a skilled maker. Once the parchments have been prepared, the entry goes on, they must be cut into the correct sizes for their designated uses: as quittances or receipts, patents, parliamentary and legal records, marriage licenses, chancery documents, and so on, with the size of each specified. The entry concludes on a skeptical note concerning the putative origin of one particular variety of vellum (“so called because it is made from the skin of a dead calf,” the author notes): “There is also parchment made from the skin of a stillborn lamb, but it is extremely thin and only used for delicate work, such as in the making of fans; it is called virgin parchment; some believe that this kind of parchment is made from the membrane that covers the heads of some newborns; but this is an error engendered by superstition.”

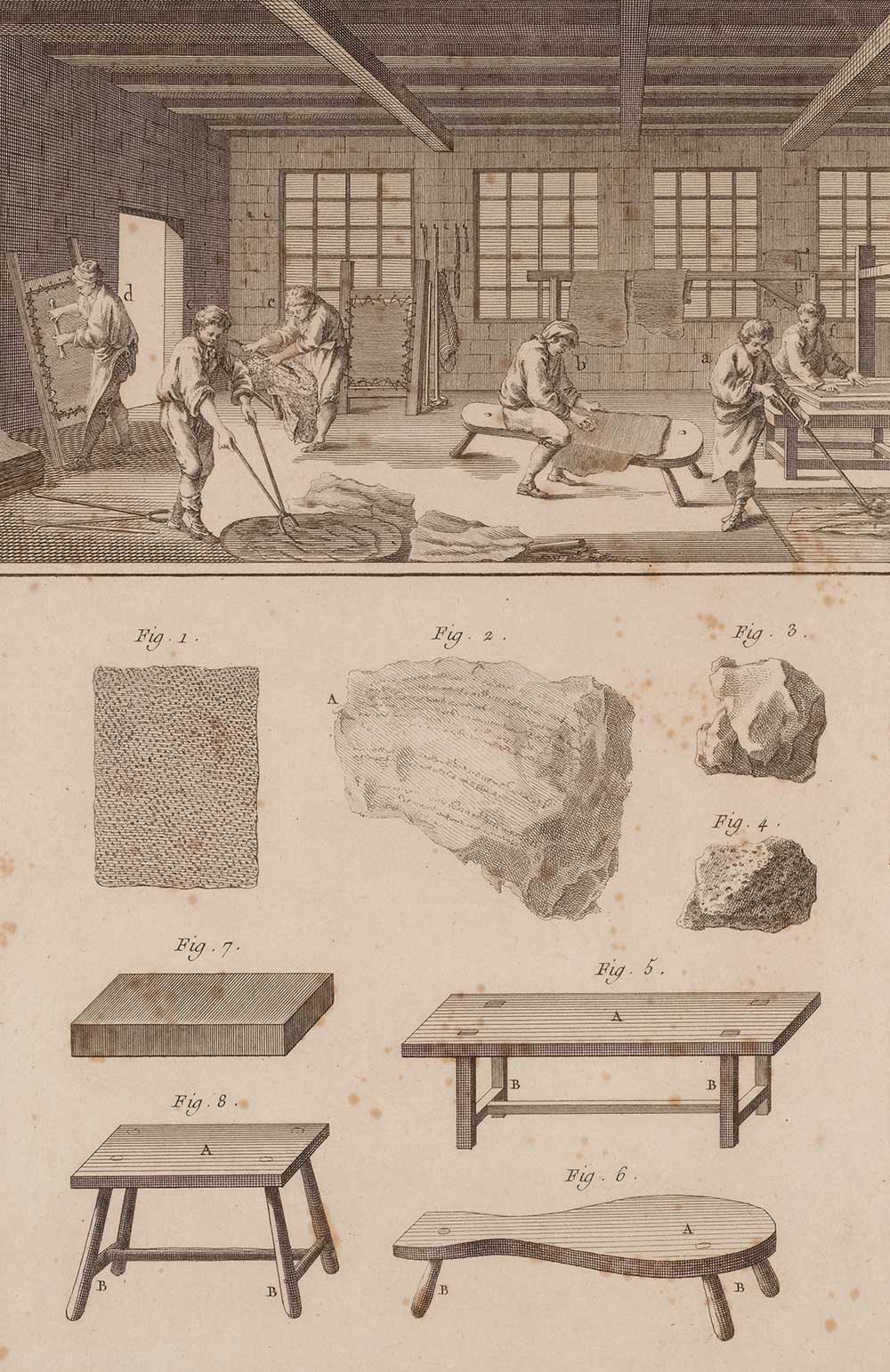

The Encyclopédie’s illustrations of parchment manufacture present the craft as a thriving and ordered industry, with neat arrays of tools and equipment, no sign of besmeared laborers or flayed carcasses, a workshop neat as a pin. In true eighteenth-century fashion, Lalande’s entry on parchemin exhibits all the Enlightenment confidence about an endlessly complicated and refined practice, here stripped of its animality and its mess, the gristle and stink that suffused the parchment industry of the premodern world. Printed on paper and intended for mass consumption, the entry and its plates present the craft in terms of its transparency: clean lines, a clear process, a known history of utility from the beginnings of human civilization to modernity’s nascent industrial present. The parchment, in this worldview, is flawless.

Excerpted from On Parchment: Animals, Archives, and the Making of Culture from Herodotus to the Digital Age, by Bruce Holsinger, published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2022 by Bruce Holsinger. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/oURH5tY

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.