Top line: The problems of boys and men are real and dangerously neglected. This newsletter is about those problems - and what to do about them. I also wrote a book on the topic, Of Boys and Men:

Stat of the week: In 1972, men were 13 percentage points more likely than women to get a bachelor’s degree. That’s when Title IX was passed to help women. Now women are 15 percentage points more likely than men to get a bachelor’s degree. So gender inequality in higher education is wider today than it was fifty years ago, but the other way round. (Check out this Brookings piece I wrote with Ember Smith digging into some of these numbers.)

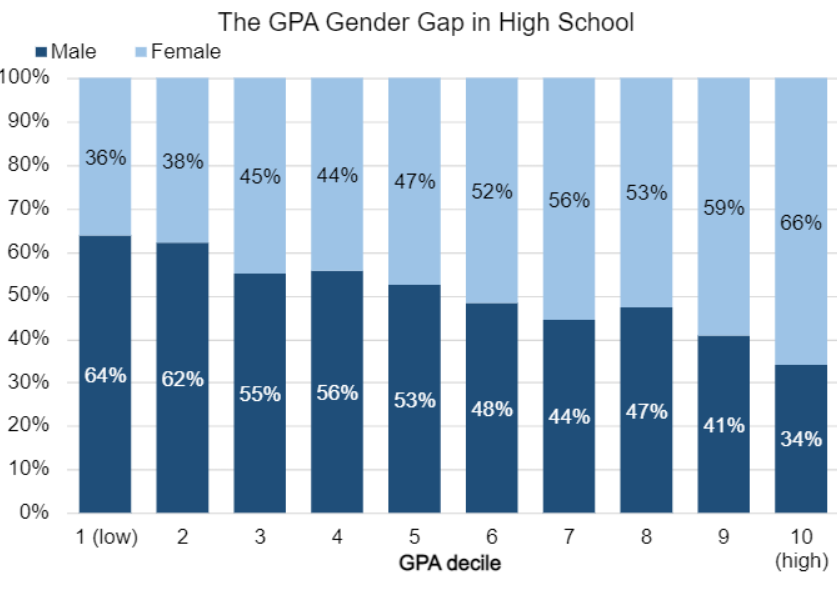

Chart of the week:

Why it matters: Education is the foundation for a good career and a flourishing life. And it is the poorest boys who are having the hardest time in the classroom. If we care about equality and opportunity, we need to face this growing problem. Now.

What I’ll be covering

I’ll be writing here weekly, on a wide range of important topics related to boys and men, including education, jobs, sex, fatherhood, masculinity, politics, sex, friendship, mental health, and much more.

You are receiving this because either:

-

You’ve already subscribed to receive my newsletters.

-

Some brilliant person has forwarded it to you.

Either way, thank you. But I really don’t want to spam you. So, if you’d prefer not to get this newsletter, it’s easy to unsubscribe with the link at the bottom. If you’ve not subscribed yet, you can do here:

For this first post, I thought I would simply share the Preface to the book Of Boys and Men to give you a sense of the ground it covers and my goals in writing it.

Also, if you feel like sharing this post to help me reach a wider audience for the newsletter as I start out on this journey, I’d be grateful:

I’m proud that the book has received some wonderful advance praise, including this from Tyler Cowen of George Mason University:

"One of the most important books of this year, perhaps the most important."

And this from NYU Professor Jonathan Haidt:

"Speaks to our hearts as well as our heads. A powerful and important book."

And this from the President of New America, Anne-Marie Slaughter:

“As a feminist who is deeply committed to gender equality and a mother of two young men, I highly recommend Of Boys and Men.”

Preface: Worried Dad to Worried Wonk

I have been worrying about boys and men for 25 years. That comes with the territory when you raise three boys, all now grown men. George, Bryce, Cameron: I love you beyond measure. That’s why, even now, I sometimes worry about you. But my anxiety has spilled over into my day job. I work as a scholar at the Brookings Institution, focusing mostly on equality of opportunity, or the lack thereof. Until now, I have paid most attention to the divisions of social class and race. But I am increasingly worried about gender gaps, and perhaps not in the way you might expect. It has become clear to me that there are growing numbers of boys and men who are struggling in school, at work, and in the family. I used to fret about three boys and young men. Now I am worried about millions.

Even so, I have been reluctant to write this book. I have lost count of the number of people who advised against it. In the current political climate, highlighting the problems of boys and men is seen as a perilous undertaking. One friend, a newspaper columnist, said, “I never go near these issues if I can avoid it. There’s nothing but pain there.”

Some argue that it is a distraction from the challenges still faced by girls and women. I think this is a false choice. As an advocate for gender equality, I think a lot about how to close the pay gap between women and men. (For every $100 earned by men, women earn $82.) As you will see, I think the solutions here include a more equal allocation of childcare, helped by generous paid leave for both mothers and fathers. But I am just as worried about the college degree attainment gap in the other direction, which is just one symptom of a large and growing gender gap in education. (For every 100 bachelor’s degrees awarded to women, 74 are awarded to men.) Here I propose a simple but radical reform: start boys in school a year later than girls.

In other words, redesign jobs to be fairer to women, and reform schools to be fairer to boys.

We can hold two thoughts in our head at once. We can be passionate about women’s rights and compassionate toward vulnerable boys and men.

I am of course hardly the first to write about boys and men. I follow in the footsteps of Hannah Rosin (The End of Men), Andrew Yarrow (Man Out), Kay Hymowitz (Manning Up), Philip Zimbardo and Nikita Coulombe (Man, Interrupted), and Warren Farrell and John Gray (The Boy Crisis), among many others. So why this book, and why now? I wish I could say that there was a single, simple motivation. But there are six main reasons.

First, things are worse than I thought. I knew some of the headlines about boys struggling at school and on campus, men losing ground in the labor market, and fathers losing touch with their children. I thought that perhaps some of these were exaggerated. But the closer I looked, the bleaker the picture became. The gender gap in college degrees awarded is wider today than it was in the early 1970s, but in the opposite direction. The wages of most men are lower today than they were in 1979, while women’s wages have risen across the board. One in five fathers are not living with their children. Men account for almost three out of four “deaths of despair,” either from a suicide or an overdose.

Second, the boys and men struggling most are those at the sharp end of other inequalities, especially of class and race. The boys and men I am most worried about are the ones lower down the economic and social ladder. Most men are not part of the elite, and even fewer boys are destined to take their place. In 1979, the weekly earnings of the typical American man who completed his education with a high school diploma, was, in today’s dollars, $1,017. Today it is 14% lower, at $881. As The Economist magazine puts it:

“The fact that the highest rungs have male feet all over them is scant comfort for the men at the bottom.”

Men at the top are still flourishing, but men in general are not. especially if they are Black:

“To be male, poor, and African-American is to confront, on a daily basis, a deeply held racism that exists in every social institution,” writes my colleague Camille Busette. “No other demographic group has fared as badly, so persistently and for so long.”

Black men face not only institutional racism but gendered racism, including discrimination in the labor market and criminal justice system.

Third, it became clear to me that the problems of boys and men are structural in nature, rather than individual; but are rarely treated as such. The problem with men is typically framed as a problem of men. It is men who must be fixed, one man or boy at a time. This individualist approach is wrong. Boys are falling behind at school and college because the educational system is structured in ways that put them at a disadvantage. Men are struggling in the labor market because of an economic shift away from traditionally male jobs. And fathers are dislocated because the cultural role of family provider has been hollowed out. The male malaise is not the result of a mass psychological breakdown, but of deep structural challenges.

“The more I consider what men have lost—a useful role in public life, a way of earning a decent and reliable living, appreciation in the home, respectful treatment in the culture,” writes feminist author Susan Faludi in her 1999 book Stiffed, “the more it seems that men of the late twentieth century are falling into a status oddly similar to that of women at mid century.”

Fourth, I was shocked to discover that many social policy interventions, including some of the most touted, don’t help boys and men. The one that first caught my eye was a free college program in Kalamazoo, Michigan. According to the evaluation team, “women experience very large gains,” in terms of college completion (increasing by almost 50%), “while men seem to experience zero benefit.” This is an astonishing finding. Making college completely free had no impact on men. But it turns out that there are dozens of programs that benefit girls and women, but not boys and men: a student mentoring scheme in Fort Worth, Texas; a school choice program in Charlotte, North Carolina; an income boost to low-wage earners in New York City, and many more. The striking failure of these interventions to help boys or men is often obscured by a positive average result, driven by the positive impact on girls or women. In isolation, this gender gap might be seen as a quirk of a specific initiative. But it is a repeated pattern. So not only are many boys and men struggling, they are less likely to be helped by policy interventions.

Fifth, there is a political stalemate on issues of sex and gender. Both sides have dug into an ideological position that inhibits real change. Progressives refuse to accept that important gender inequalities can run in both directions, and quickly label male problems as symptoms of “toxic masculinity.” Conservatives appear more sensitive to the struggles of boys and men, but only as a justification for turning back the clock and restoring traditional gender roles. The Left tells men, “Be more like your sister.” The Right says, “Be more like your father.” Neither invocation is helpful. What is needed is a positive vision of masculinity that is compatible with gender equality. As a conscientious objector in the culture wars, I hope to have provided an assessment of the condition of boys and men that can attract broad support.

Sixth, as a policy wonk I feel equipped to offer some positive ideas to tackle these problems, rather than simply lamenting them. There has been enough handwringing. In each of the three areas of education, work, and family, I provide some practical, evidence-based solutions to help the boys and men who are struggling most. (It is probably worth saying upfront that my focus is on the challenges faced by cis heterosexual men, who account for around 95% of men.)

-

In part 1 of the book, I present evidence on the male malaise, showing how many boys and men are struggling in school and college (chapter 1), in the labor market (chapter 2), and in family life (chapter 3).

-

In part 2, I highlight the double disadvantages faced by Black boys and men, suffering from gendered racism (chapter 4), as well as for boys and men at the bottom of the economic ladder (chapter 5). I also present the growing evidence that many policy interventions don’t work well for boys and men (chapter 6).

-

In part 3, I address the question of sex differences, arguing that both nature and nurture matter (chapter 7).

-

In part 4, I describe our political stalemate, showing how instead of rising to this challenge, politicians are making matters worse. The progressive Left dismisses legitimate concerns about boys and men and pathologizes masculinity (chapter 8). The populist Right weaponizes male dislocation and offers false promises (chapter 9). For the partisans, there is either a war on women or a war on men.

-

Finally, in part 5, I offer some solutions. Specifically, I make proposals for a male- friendly education system (chapter 10); for helping men to move into jobs in the growing fields of health, education, administration, and literacy, or HEAL (chapter 11); and for bolstering fatherhood as an independent social institution (chapter 12).

“A man would never get the notion,” wrote Simone de Beauvoir, “of writing a book on the peculiar situation of the human male.”

But that was in 1949. Now the peculiar situation of the human male requires urgent attention. We must help men adapt to the dramatic changes of recent decades without asking them to stop being men. We need a prosocial masculinity for a postfeminist world. And we need it soon.

Thanks for reading, sharing, preordering etc. and if you think it worthwhile, please consider sharing this newsletter with your networks:

Next week I’ll turn to the challenges faced by many men in the labor market, as we move away from traditionally “male” blue collar jobs and towards traditionally “female” pink-collar jobs. (Spoiler: we need a lot more male teachers and nurses…)

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/BrmbPfc

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.