A few years ago I read Walter Isaacson's biography of Benjamin Franklin. I came across a description of Franklin's Junto, a discussion club to "debate philosophical topics, devise schemes for self-improvement, and form a network for the furtherance of [careers]." A feeling awoke in me and I wanted something like this, so I started my own Junto and ran a wide-ranging collection of discussions for several months.

That desire to build a group of like-minded people and tackle different challenges was magnetic. I've always thought of this quote from Alexis de Tocqueville, and while he points out a common trait among Americans I believe this represents an urge everyone has to associate, regardless of nationality:

"Americans of all ages, all conditions, all minds constantly unite. Not only do they have commercial and industrial associations in which all take part, but they also have a thousand other kinds... If it is a question of bringing to light a truth or developing a sentiment with the support of a great example, they associate."

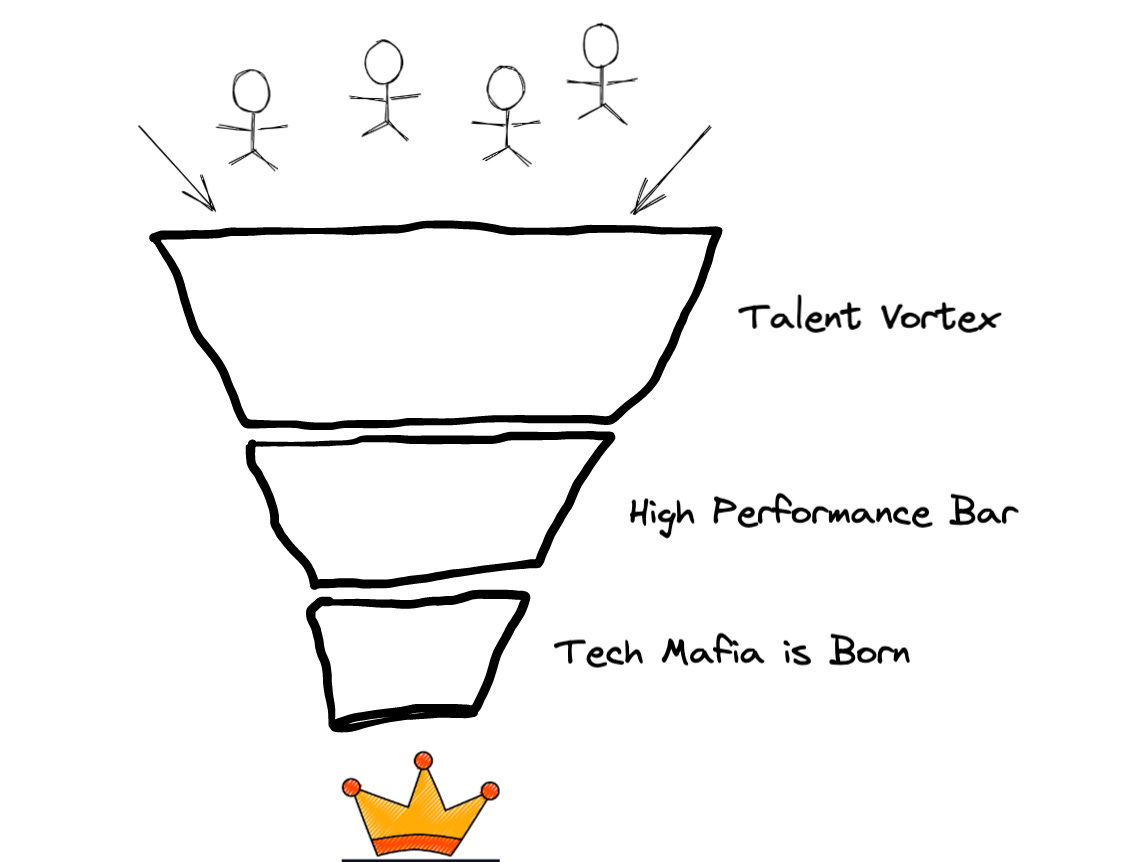

This concept of associating is how I think about building businesses. People want to associate, but very talented people want to associate with other very talented people. I've written before about talent vortexes; this idea that a talented group of people starts to become self-perpetuating.

"Creating a talent vortex sounds like something everyone will say they have but very few companies actually do. When you ask the smartest people you know "where are the smartest people YOU know going to work?" you can't fake it when the response starts to get consistent."

As an investor one of the most critical things you can do is identify and support the companies run by the smartest people who are getting the best people into the best positions to drive success. There is a lot to learn when you identify pools of talented people and why they came together. One of the most famous "associations" of very talented people? The PayPal Mafia.

It's unlikely you haven't heard of the PayPal mafia, but if you haven't it's harder still to believe you haven't heard of something that one of them created or funded. The members of the mafia included Peter Thiel, Max Levchin, Elon Musk, Reid Hoffman, and Roelof Botha, among a host of others.

As a group they've been involved in almost every major company built in the last 20 years. YouTube, Linkedin, Square, Yelp, Tesla, Affirm, Facebook, Reddit, and the list goes on and on.

Last year Jimmy Soni wrote a book called "The Founders," and one of the key things he points out is that while most people focus on what the PayPal Mafia did after PayPal the core takeaways are what they learned during PayPal that enabled them to go on to be so successful.

The book is incredible. I'd also highly recommend a podcast that Jimmy did with Frederik Gieschen. He lays out a few core ideas of what contributed to the culture of success that PayPal built.

"The three of them (Peter Thiel, Elon Musk, and Max Levchin) are not going to hire people that cannot operate at the level they can operate. I discovered the high bar that was placed on hard work, aggressiveness, intellect, puzzle-solving, a kind of disposition to find the answer vs. leaning on experience. You have three leaders who set the tone for a culture of intelligence and intensity. They learned a way of operating and very fast problem solving."" (Jimmy Soni)

The example that these three leaders in particular set was more than just a hiring manual or lip service. They just weren't going to tolerate people who couldn't perform at their level and that set the bar for the rest of the organization.

"This was not a place for the faint of heart. It was a place with really high IQ points and a lot of intense battling over ideas. Building a team that has the capacity to do that strikes me as one of the hardest things to do in business. Because it requires a few things. One, you have to be courageous enough to walk into a room with [one of these people] and tell [them] that [they're] wrong. Which is not easy. The second is you have to actually think very hard about what the right answer is in a given context. Not what you think about the person presenting the idea. You have to think about the idea itself. And then the third thing is you have to do this despite the fact the person talking to you might be a subordinate or three levels above you. It has to be done irrespective of hierarchy because the thing you care about is the idea. We as human beings have the tendency to slouch in the direction of hierarchy absent other things." (Jimmy Soni)

Being able to go toe-to-toe with very smart people and stay completely focused on the quality of the idea independent of the person presenting it isn't very easy. But it represents the kind of first principles thinking required in order to make sure that every decision is being made appropriately.

Elon Musk talks all the time about first principles. "It is important to view knowledge as sort of a semantic tree — make sure you understand the fundamental principles, like the trunk and big branches, before you get into the leaves/details or there is nothing for them to hang on to." Before you can get into the problems that need to be solved you have to be confident that everyone is meeting your initial expectation. Once you're confident everyone is focused on finding the best ideas regardless of hierarchy (first principles) then you don't have to stop and evaluate every single decision that gets made.

Another example of a PayPal Mafia-adjacent company is Ramp. Keith Rabois was an executive at PayPal and now, as a partner at Peter Thiel's Founder's Fund, led several rounds of funding at Ramp. Ramp is a company that has been in the news a lot recently after raising money at an $8B+ valuation.

The leaders at Ramp have consistently pointed to a similar first-principles idea that they see high expectations as the starting point from which they build. Every aspect of the business has a core focus on quality and the results speak for themselves. Their emphasis is on customer focus, product obsession, and commitment to talent. Growth is just the output of those core first principles.

And believe me. Ramp has put out some serious growth. They're one of the fastest companies to reach $100M of ARR.

"I think this is a part of the secret sauce. A group of employees that are able to engage on ideas in this way at this level with this kind of intensity, but to do so with at least a modicum of respect." (Jimmy Soni)

Again, the first principles here are to focus on finding the very best people who you can trust to look for the best answer to any question. Jimmy tells the story of an engineer who interviewed at PayPal and went home to tell his wife he had to take the offer even though he'd make less money. "Everyone I interviewed with is smarter than me. So I may not make as much money but I'm going to learn a lot there."

There is a particular kind of person that is drawn to a culture that focuses on the quality of the learning experience over the size of the paycheck. Smart people want to associate with smart people because they know they can trust them to find the best solution, and that they themselves will be held to the highest standard. That's how talent vortexes are born.

PayPal isn't the only company to build a tech mafia. There are a number of companies that have produced a huge amount of high quality talent like Stripe (though they probably don't love getting referred to as a mafia anymore), Segment, Dropbox, Apple, and Airbnb.

Other companies like Figma will likely see their own alumni networks spread out and build more world-class companies once they have more time. A lot of the best people at Figma are still there basking in the glory of their meteoric rise. If a tech mafia is the outcome of a high concentration of talent then the input is a successful talent vortex.

This idea of a "tech family tree" is common among startups but rarely discussed. The idea is that when talented people have worked at other great talent vortexes you associate with really smart people. Then as you build something you're able to find the smartest people you worked with before and try and convince them to join your new company.

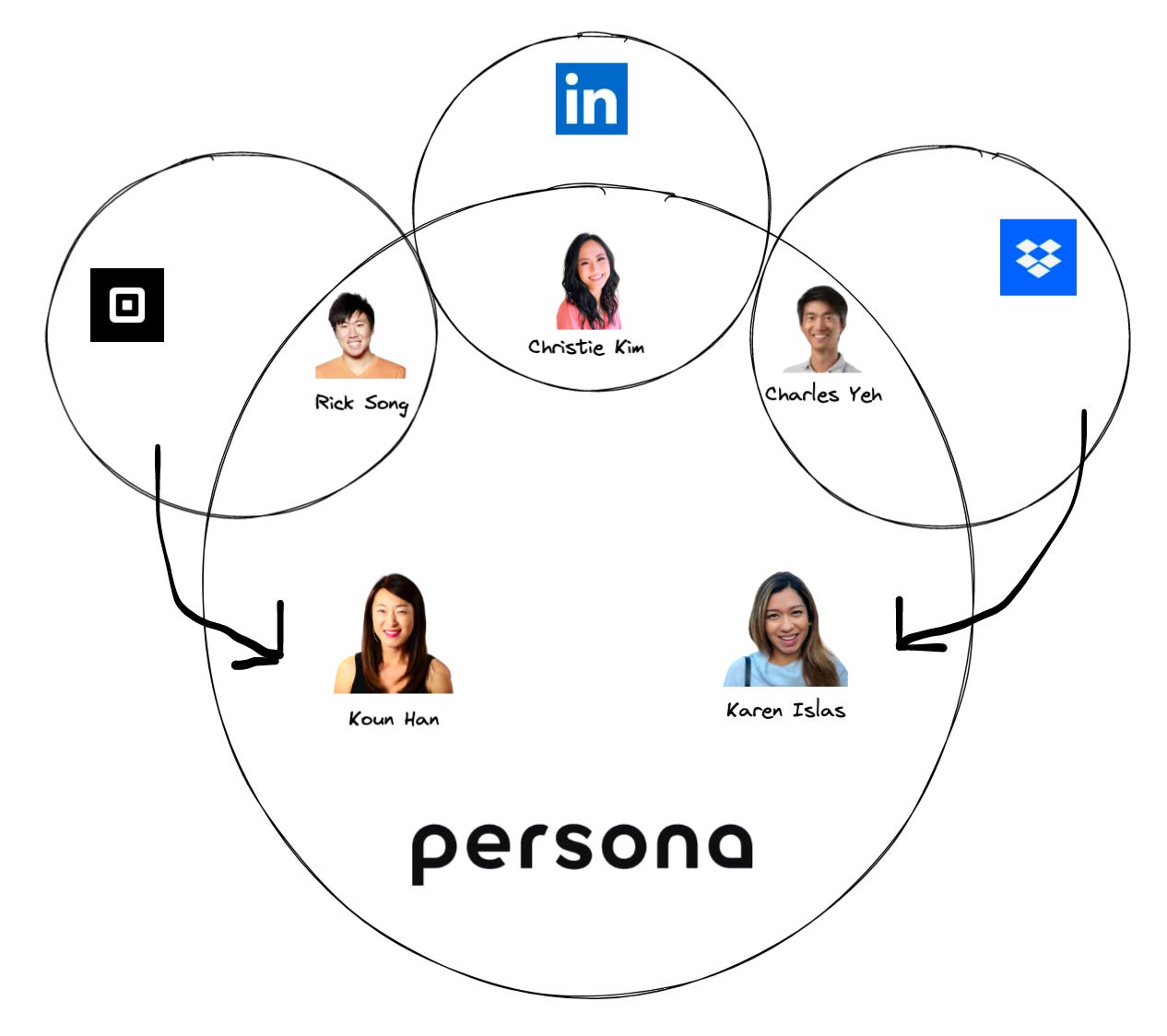

A great example of this is Persona. I had the privilege to invest in Rick, Christie, and Charles as they've gone about building a new way of thinking about identity online. They came from Square, Linkedin, and Dropbox. All three of those companies have been talent vortexes in their own right over time. Now Persona is building from that starting point.

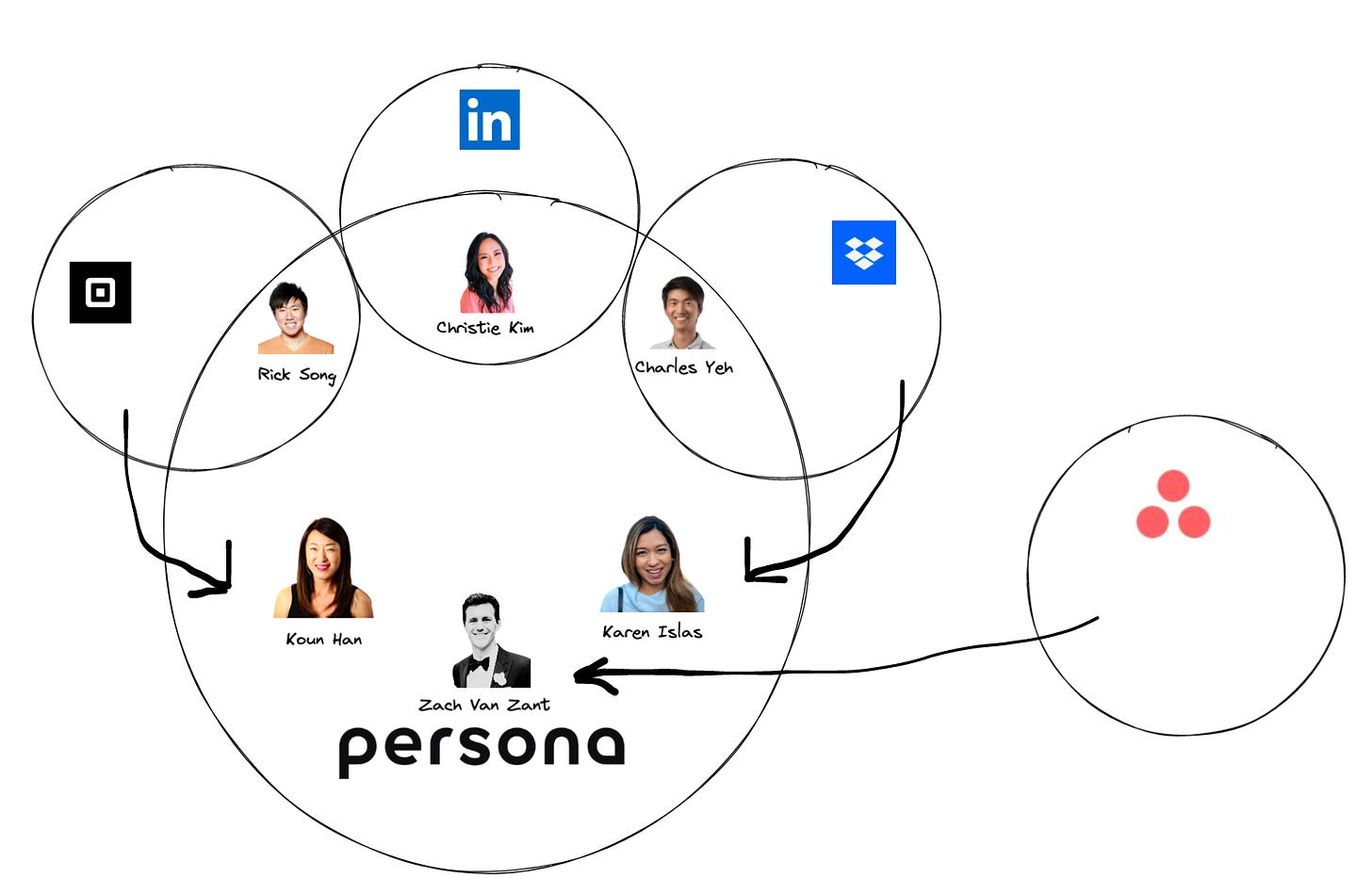

One of the most impactful things an investor can do is introduce new DNA into a budding talent vortex. If you do it right you're bringing the best that another company ecosystem has to offer. An example of this: Erik Kriessmann is someone I worked with at Index and he introduced Zach Van Zant to the team at Persona as a VP of Sales who came from Asana.

There is a fascinating web of people working across a variety of companies. But even more interesting than the never-ending list of Linkedin profiles that overlap is a cross pollination of playbooks. For example, Jimmy Soni talks about this in the PayPal podcast. The founders of YouTube came from PayPal and took a page right out of the PayPal playbook on distribution. Just like PayPal had gotten their payment buttons embedded right on the homepage of online stores, YouTube worked to build embeddable videos that to this day are still one of the most effective methods of embedding videos and driving distribution of a specific media type.

So if the way to create this powerful association of smart people within a company comes from a talent vortex; how do you build one? The best summary I've seen of the key idea here is in The Everything Store about Amazon. Jeff Bezos hired Jeff Wilke in 1999 to build out their operations team.

"Immediately upon moving to Seattle, Wilke set about filling the ranks of Amazon’s logistics division with scientists and engineers rather than retail-distribution veterans. He wrote down a list of the ten smartest people he knew and hired them all."

We can dig into the details but if you have to take away one thing it is this idea of "hiring the smartest people you know." A couple risks in that. You need to make sure you know really smart people. And you need to make sure you can effectively sell the smartest people you know on something or else you're stuck with the more gullible 37th smartest person you know.

Just a side note. This is a big reason why I have nuanced advice for people who are deciding whether to work on a startup of their own right out of school vs. getting a job. There are great examples of people building something without any prior experience. Dylan Field started Figma without even finishing college. Larry and Sergey at Google, Max Levchin. If you have the inclination to build something then go for it. But if you're just starting something for the sake of starting something you can do yourself some favors to increase your odds of success. One of those favors is joining a talent vortex first to make sure you're spending time around very smart people.

When it comes to building a talent vortex I went right to the source and talked with people across companies that have produced high quality talent. Stripe, Airbnb, Dropbox, Plaid, etc. I was surprised by how consistent the feedback was on what these people saw as the most critical ways of building a talent vortex. And how similar they were to some of the things that Jimmy Soni mentioned about PayPal.

Across the board the most consistent answer that everyone gave who grew up in one of these talent vortexes was the idea that when the talent quality was at its highest it came as a result of keeping an incredibly high bar for who was allowed in to the company.

Identifying the right initial people to kick off a talent vortex is crucial because the first 10 people who get hired will likely hire the next 90. In terms of identifying the most crucial characteristics of those critical contributors, Keith Rabois talks about this idea of "barrels and ammunition." (Special thanks to Mark Temple who reminded me of the video.) The key idea is that most people are actually mostly good ammunition; high quality but require something to point them in the right direction.

"What you need in your company are barrels and you can only shoot through the number of unique barrels you have. And then you stock those with ammunition so that you can do a lot. Barrels are incredibly difficult to find but when you have them give them lots of equity, promote them, take them to dinner every week."

Another way of describing these people who will continue to set an incredibly high bar came up frequently when I talked to people who came from Stripe. Stripe puts an emphasis on identifying what I started referring to in short hand as "systems thinkers." Stripe would rather find someone who wants to "write the book" on how to do something vs. just finding someone who has had a big title.

"Promotions went not necessarily to the top performers, but those that in addition to clearing the bar, built systematic solutions for problems they were running into (a better training, a new framework for dealing with something, an industry-specific application of our products that would impact other customers." (Former Stripe Employee)

Brie Wolfson, who spent almost 5 years at Stripe working across operations and Stripe Press wrote a phenomenal overview about their writing culture:

"I’ve come to believe that Stripe’s culture of writing is one of the organization’s greatest superpowers. As startup whisperer, patio11 puts it, “Stripe is a celebration of the written word which happens to be incorporated in the state of Delaware.” Half of the story of what makes this so would be obvious to onlookers–Stripe has always treated documentation as a first-class product."

Now it may start to feel like we've wandered. "What does a writing culture have to do with keeping a high talent bar?" But to me the connection between an emphasis on writing and a selection-bias for systems thinkers was super clear. The very best people that kick off these talent vortexes are those who are most capable of building a system. The "barrels" and "systems thinkers" are all, in effect, entrepreneurs. Willing to take ownership of what this organization becomes.

Like I mentioned earlier, this idea came up in the podcast with Jimmy Soni. The constant focus on the quality of the output regardless of the person.

"You have to actually think very hard about what the right answer is in a given context. Not what you think about the person presenting the idea. You have to think about the idea itself. It has to be done irrespective of hierarchy because the thing you care about is the idea."

The kiss of death for any company is when the titles become more important than the ideas. If you find yourself having more meetings about roles, responsibilities, and "territories" than you do about problems, ideas, experiments, and solutions? You're in trouble.

Gokul Rajaram wrote a masterpiece on titles that every organization with more than one person should read. The key idea revolves around "building a culture where scope and impact — not titles — are recognized and celebrated."

Every time a company celebrates a title change they "undermine the perception of the company as a meritocracy." The focus should instead be targeted on finding and amplifying those great people who are focused on the scope and impact of their work. Not titles. In the words of Keith Rabois? "Barrels."

"Pay attention to whose desks people go up to. Especially people who they don't report to. If your employees go up to someone who they don't report to its a sign that they believe that person can help them. And if you see that consistently those are your barrels."

No one gets promoted to become the official "go-ask-so-and-so" person. That right is earned by being the smartest person who can think through both big picture and the small details. Reward that. Regardless of title.

This ties pretty closely into the idea of focusing on a meritocracy where the best ideas are rewarded. Many of the best talent vortexes had a focus on people who had demonstrated early potential and career trajectory rather than tenure. Someone who has performed exceptionally in some aspect of life and seen their career inflect quickly is likely more hungry than someone who has been trudging along in the same role for 5+ years. Someone like this is hungry for more.

This idea of focusing on potential came up again and again. Alex Allain, who was the Director of Engineering at Dropbox for 7 years, wrote a guide laying out what he learned in conducting 500+ technical interviews at Dropbox. The ability to identify potential is actually a skill; not just a choice. Alex lays out how some exceptional interviewers could become the difference between identifying average talent and diamonds in the rough.

"Expert interviewers are often the reason a candidate joins a company. They may spot a candidate that might otherwise have gotten rejected but has some hidden strengths—several times at Dropbox I witnessed an eagle-eyed talent scout push for a candidate who became an exceptional hire, and one that we’d have missed out on without that expert eye. They’re also talent magnets—people want to work with them because they bring tons of positive energy, make a deep connection with the candidate, or otherwise show that they’d be a fantastic coworker."

A lot of the people who expressed a huge amount of gratitude for how quickly they grew within a talent vortex pointed to the people that pushed them. Whether it was at the founder level or individual managers. There was a consistent thread of people lifting each other to perform at a higher capacity than they thought possible of themselves. Keith Rabois talks about this as "scope expansion."

"You give them a small set of responsibilities. And then if they succeed at that you can give them something more consequential to do. And that's what you want to do with every employee every day: expand the scope of their responsibilities until it breaks. And it will break, everyone breaks. But when you find the level of sophistication they can handle that's the role they should stay in."

As an investor my focus is on identifying great people. The vast majority of venture firms are completely company-centric. They want to see good talent signal, but they're primarily focused on the overall company. In venture the caliber of the people is an incredible indicator that is almost never appreciated enough.

More people need to aspire to building the next great Bells Labs or Xerox Parc or PayPal Mafia. Not because of the outcomes but because of the power of the association. Find the next great network of people and support them maniacally in any way you can.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/GzstqJ5

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.