For a long time, I found the micromanager CEO archetype very frustrating to work with. They would often pop out of nowhere, jab holes in the work I had done without understanding the tradeoffs, and then disappear when I wanted to explain my decisions. In those moments, I wished they would trust me based on my track record of doing good work. If they didn’t trust my track record, could they at least take the time to talk through the situation so I could explain my decisions?!

At those moments, I longed for a more distant CEO, who benevolently approved my headcount requests and occasionally sent me a note confirming my inherent genius, but otherwise left me to do my work. They would, of course, still care about the work I do, so they might expect me to generate some monthly metrics and reports on the team’s execution, which I would dutifully provide. As I spoke with industry peers, I was surprised to realize that the CEO-at-a-distance does exist. There are many CEOs who act that way, but my peers engaging with them weren’t celebrating working with them. In fact, they were quite frustrated.

Where I’d imagined an absentee CEO would feel empowering, instead it usually meant that the executive team couldn’t move important decisions forward. When the executives did make progress, it was by accepting whatever outcome they could build consensus around, rather than making the best possible decisions. If another executive was struggling or behaving badly, the absentee CEO wouldn’t address the issue until it became dire, and executives who tried to raise concerns earlier were branded as hard to work with.

Executives who’ve worked with micromanager and absentee CEOs would almost uniformly prefer to work with a micromanager. Not because they enjoy the micromanager, but because the micromanager moves things forward. If you care about impact, it’s better to make forward progress with pockets of frustration than to languish indefinitely, and all successful executives care about impact.

Ideally you should neither micromanage nor disengage from your team. Many managers do drift into one behavior or the other, and if you must, I believe quite strongly that being a bit of a micromanager is the better choice than being disengaged. Teams chafe under micromanagement, but teams atrophy without ongoing attention, which disengaged leaders don’t provide. For all the complaints about micromanagement, being a disengaged manager will cause significantly worse outcomes.

Becoming a disengaged manager

When I push managers to proactively inspect their team’s work, a frequent concern from well-intentioned managers is that they don’t want to become micromanagers. I sympathesize with that anxiety, having experienced it in my own leadership journey: my early management years were best characterized as having a number of micromanagement tendencies that I had to slowly unlearn.

One way I worked against my instincts was being less aware of some day-to-day particulars. My rationale was that if I didn’t know what was happening, I was less likely to get caught up trying to optimize it. Designed ignorance became much easier to implement as the scope of my managerial duties grew, as I learned about systems thinking, and as I internalized The E-Myth Revisited’s core message: leaders work on the system, not in the system. I eventually connected my approach with the Deists’ watchmaker analogy, which I’d learned about in a high-school US History class. That analogy argues that God created the world, and is now letting it run without interference, much like a watchmaker manufactures a watch, and then lets it run. Maybe, I thought to myself, that’s also the right way to manage a team.

It’s not, it turns out, but it took me a while to figure that out.

Why do managers become disengaged?

My stint as a disengaged manager was inspired by an attempt to micromanage less, but managers become disengaged for many reasons. Clustering those reasons together, I’ve generally found that managers become disengaged for three broad reasons:

- External demands have broken the manager’s work systems. This might be an aging parent, a young child, or a personal sickness. Their previous work habits are no longer supporting their success, and they haven’t built new habits to compensate

- Manager’s pursuit of “enlightened distance” to avoid micromanagement has gone too far. Instead of digging into the details, they tell their team that they trust them, and encourage them to follow what makes sense to them. This culminates in the manager ignoring their team rather than empowering it

- Manager is chasing energy and will continue to drift towards wherever energy accumulates in their life. This might be executives always reacting to internal fires and losing sight of their team’s core work. It can also be an executive who becomes very active or loud in their angel investing because they’ve become bored with their work

The first two categories–spike in external demands and enlightened distance–are the sorts of things that can be diagnosed and solved by a helpful manager. Admittedly, as you get further into your career, you’re increasingly unlikely to have a helpful, attentive manager, but it’s still likely that a peer will nudge you (“it feels like you’ve been a little distracted recently”) or that you can self-diagnose (“how would I know if my team was really struggling right now, without someone proactively telling me?”).

The final category, disengaged because you’re chasing energy elsewhere, is the hardest to resolve, and often requires some messy tradeoffs.

Chasing energy

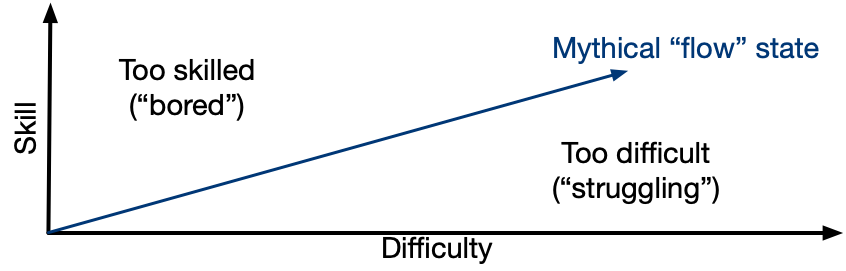

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi has written two delightful books, Creativity and Flow, and the latter is particularly helpful in introducing a chart that shows the relationship between a participant’s skill, a scenario’s challenge, and their likelihood of reaching the flow state. An expert programmer is unlikely to attain flow when doing rote programming work. A beginning programmer is unlikely to attain flow when doing extremely difficult programming work. Flow is most easily achieved when experiencing a challenge that is at, or just slightly above, your current skill level.

So, too, it goes for executive engagement.

When executives start looking elsewhere for energy–whether it’s falling behind on core work duties or “angel investor” popping up next to their name on LinkedIn–it’s almost always because their role is too challenging, or not challenging enough. The former happens most frequently when an executive remains with a company as their role significantly expands in scope. At some point, they struggle to quickly make the next leadership leap, with a particularly high degree of challenge when moving from managing a team to managing an organization. The latter happens when a company’s pace of improvement is low relative to the company’s capabilities. Note that pace of improvement correlates somewhat weakly with general pace: there are many companies that move quickly without accomplishing too much.

If you determine an executive is overmatched by the role, the playbook is the same as it would be for any other team member: help them identify and address their gaps. Once again, the typical lack of an engaged manager is an obstacle here, and generally improvement is driven by their peers, paid coaches, or informal mentors.

If the executive is undermatched by the role, then it’s an entirely different discussion. It’s about finding ways to engage them in and out of their work. Outside of work, a surprising number of senior leaders are underwater in their personal lives such that they struggle to be present in their work. You can’t solve that for them, but you can help them build awareness of the challenge, and encourage them to become more proactive in managing their time and energy. Life has a way of getting complex as you get older, and it’s easy to glide onward as if it hasn’t. That’s a slow, subtle recipe for exhaustion.

If energy is missing from within their work, it’s much easier to be helpful.

The standard advice is to assign more work. For example, identify an interim assignment supporting an additional team, or assign them a project to drill into a major business issue. Those can be helpful, but I think they subtly miss the diagnosis. Executives disengage from their work when they begin to subtly believe that doing better doesn’t matter much. You won’t resolve that by giving them more work, but instead by paying attention to the work they’re already doing.

Take a month to deliberately engage in their work: make sure they know that you directly care about their and their team’s work. Push into the details just enough that it ensures they in turn are paying attention to their teams work in detail, motivating their teams in turn. In other words, micromanage them, just a bit.

Maybe it’s core work, afterall?

While testing drafts of this essay, one piece of feedback that came up a few times was that angel investing and other “chasing energy” projects can be a core part of an executive’s responsibilities. By investing, you get more exposure to different companies doing different things, which deepens your understanding of the ecosystem you’re operating in. This absolutely can be true, and depends on the details of the project and the executive.

Taking the example of angel investing, my general perspective is that this is a bit less true than many executives hope. You will learn a tremendous amount doing your first ten angel investments, but significantly less on your 20th and 30th investment. If an executive is dipping their toes in to understand the process, get some perspective, and build some connections, then I’d be swayed that this is a high impact use of time. I’d be significantly less convinced that this was their core work, rather than a form of self-energizing, if they continued to invest actively after building an initial portfolio.

Finding the way forward

Executives are human, and each human is energized by certain work. Sometimes your work simply won’t give you the energy you need. If that’s a long-term problem–will you feel this way a year from now?–then you might be in the wrong role. More often than not, this is a temporary challenge, as interesting new problems will pop up in a month or two. Rather than finding a new role, you just need to find a way to stay engaged for the interim gap before something new goes wrong.

In the best case, you’ll find a small project to contribute to until things get energizing again, but stay close to your team. It’s better to micromanage a bit than to disappear, and micromanagement will leave you far better prepared to engage with whatever new problem comes your way. Of course, as you better understand yourself and your role, you will often find better ways to create energy for yourself without disengaging the team. Move to those when you can, but until then, find the energy you need to do the work you have.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/ZJL5RTD

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.