Considering the face-melting, heart-ripping, accelerated aging and giant man-eating ants, the Indiana Jones franchise has always flirted with horror. Some of his adventures dabbled a little more than others; there’s a reason Temple of Doom outraged the PG-13 rating into existence. With the exception of spin-off novels and comics, in which the good Doctor has fought vampires, discovered dinosaurs, defeated an army of gorilla slaves and survived a place literally named Horror Island, Indiana Jones hasn’t tackled an out-and-out horror story on the big screen.

That’s not to say he didn’t come close.

In the summer of 1977, on a beach somewhere in Hawaii, two directors were hiding from the world. Steven Spielberg had barely survived the grueling production of Close Encounters of the Third Kind and George Lucas didn’t want to know how badly his sci-fi gamble Star Wars was bombing. They were musing about other projects when Lucas brought up an idea he’d been toying with for a while, a Saturday matinee James Bond. He told Spielberg he had an entire trilogy planned for his old-fashioned hero and they shook hands on the spot.

That character turned out to be Indiana Jones, and George Lucas turned out to be a liar.

Lucas only had loose concepts for adventures beyond Raiders of the Lost Ark and certainly no plans for a connected trilogy. When success all but demanded a sequel, Lucas pitched two very different, very persistent ideas – a story about the Chinese legend of the Monkey King and another set entirely in a haunted castle. Spielberg vetoed both. The Monkey King idea was too far-fetched and he’d had his fill of ghosts producing 1982’s Poltergeist.

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom opened in the summer of 1984 to an eager, confused public. It was darker, grosser and altogether less family-friendly than its predecessor. It had its fans (and more over time), but plenty of critics and baffled parents considered it an ugly insult to taste. Many compared it unfavorably to another 1984 adventure movie, Romancing the Stone. Despite being written before Raiders, everybody and their extended families called it a rip-off, but that still counted as a compliment considering the gloom of Doom. Regardless of the reception, Indiana Jones’s second adventure became the third-highest grossing movie of 1984. But the real damage, the damage behind-the-scenes, was already done.

Spielberg was hurt. Backlash over the film’s juvenile gags and careless depiction of Indian culture took on a personal sting. He needed to step away from big-budget B-movies, to prove his maturity as a filmmaker. But that didn’t stop George Lucas from working his old sequel ideas with a writer who almost made too much sense.

Diane Thomas was waiting tables in a roadside diner when she sold her script, Romancing the Stone, to Michael Douglas for $250,000. It was the eighth highest-grossing movie of 1984 on a third of Temple of Doom’s budget. The press deemed her a screenwriting “Cinderella.” Lucas took note.

Thomas’s script followed Indiana Jones on a Universal Horror-style adventure into a sprawling, haunted castle as per Lucas’s long-simmering concept. Unfortunately, she only finished the first draft before her untimely death in 1985. Not long after, Spielberg passed with the Poltergeist defense for a second time. But George Lucas wouldn’t abandon his Indiana Van Helsing idea that easily, so he found another writer from a familiar neighborhood.

Chris Columbus, fresh off of Gremlins, the fourth highest-grossing movie of 1984, took Lucas’s other direction and turned out several drafts for “Indiana Jones and the Monkey King.” At least one of these drafts, with the alternate title “Indiana Jones and the Garden of Life,” has since found its way online and provides a startling reminder of how many franchise “rules” were only cemented by Last Crusade. Columbus’s “Monkey King” includes, among other assorted strangeness, adorable pygmy sidekicks, steampunk Nazis with machine gun arms and a scene where Indiana Jones outruns a three-story-tall, one-hundred-foot long tank on the back of a rhino.

The oddest part, however, might be the opening gambit, which manages to squeeze Lucas’s entire haunted castle concept into about ten pages.

The year is 1937. Indiana Jones is on vacation in Scotland and struggling to catch trout when torch-wielding villagers interrupt him. They’re crippled with fear over the latest in series of grisly murders. How grisly, you ask?

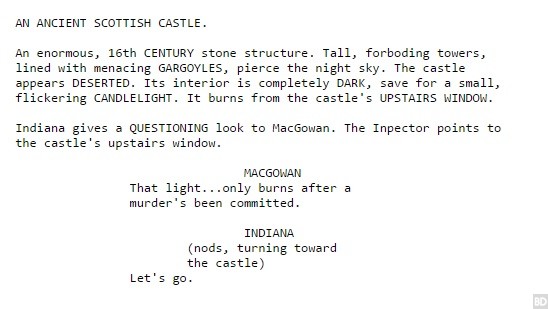

Jones, along with Inspector Scotsman MacStereotype, are enlisted to solve the case once and for all. The villagers can barely even offer ambiguous warnings about the killer not being human before a mysterious light draws the heroes to:

From there, it becomes Indiana Jones and the House of Dracula. Jones follows disembodied laughter down the castle’s labyrinthine halls, through ornate bedrooms covered in cobwebs and macabre detail. The local police get picked off one-by-one, disappearing in a split-second of darkness or, well:

Eventually, after falling through a subterranean crypt and fighting hellhounds, Indiana Jones confronts the allegedly immortal master of the house, Baron Seagrave, only for a pair of seven-foot-tall suits of armors to animate and attack. After he drops a chandelier on them, Jones holds a sword to Seagrave’s cackling throat until the authorities arrive.

Then the script casually confirms the existence of non-divine ghosts in the Indiana Jones universe:

“Indiana Jones and the Monkey King” didn’t pass Steven Spielberg’s muster either. He found it too far-fetched for an Indy adventure and it’s easy to see why. Not long after, Lucas would dig up another old sequel conceit, which Spielberg once dismissed as too spiritual. But this time he’d change his mind on the Holy Grail.

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade was the second biggest box office smash of 1989. And even if it’s not exactly haunted, Lucas finally got his castle…

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/3pKrbiN

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.