Pieter Bruegel the Elder was born around 1525 in the southern Netherlands in a tiny village named Bruegel outside the city of Breda, in southern Holland. Judging from the precision and exactitude with which Bruegel painted his pastoral scenes, his life must have been deeply rooted in such rural circumstances. There is only one snag: no such village as Bruegel, or any spot resembling that name, ever existed. And according to his biographer Alexander Wied: “There is, in fact, every reason to think that Pieter Bruegel was a townsman and a highly educated one, on friendly terms with the humanists of his time.” This suggests that Bruegel may in fact have been born in Breda.

Bruegel probably mixed with the educated humanists of Breda, but his biographer Nadine Orenstein insists that “he had not mastered Latin,” which would have been highly unusual amongst such circles. Indeed, she goes as far as to suggest that the Latin inscriptions which appear on some of his paintings were in fact written by another hand.

What is known with more certainty is that the young Bruegel travelled the thirty miles from Breda to Antwerp to begin his five-year apprenticeship in the studio of the artist Pieter Coecke van Aelst, whose paintings of religious scenes exhibited an eclectic blend of Gothic and Italian Renaissance influences. Coecke van Aelst would later be appointed court painter to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, who spent time in Antwerp in his capacity as Lord of the Netherlands and Duke of Burgundy. At the time Antwerp was the great commercial hub of northern Europe, having taken over from Bruges after the waterway linking the port of Bruges to the sea began silting up. Antwerp had a population of 100,000, a tenth of whom were foreign merchants. With Venice in decline after the discovery of the sea route to Asia around the Cape of Good Hope, and trade with the New World concentrated on ports with more direct access to the Atlantic, Antwerp was now the most cosmopolitan city in Europe.

This plunge into the overwhelming world of sophisticated reality had a profound psychological effect on the young Bruegel. Moored up along the quayside he would have seen lateen-sail barques from Portugal, three-masters which had voyaged from ports as far afield as Zanzibar and Stavanger, their cargoes loaded onto barges from Delft or Mosel, barrels being rolled across the cobbles by sailors in ragged and exotic garb, marking them out as Finnish, Scottish, or Moorish. Lined up for sale would have been opened crates of currants from Cyprus, tulip bulbs from Constantinople, reeking salted hides from the eastern Baltic, barrels of sweet wine from Sicily. He would have come across cramped groups of buyers and curious onlookers watching the auction of chained black African slaves, huddles of young mountain girls imported from the Caucasus. Yet all this went deeper than mere impressions and appearances. How could he absorb and express the sheer variety of teeming life he found milling around him amongst the vast cobbled space of the Grote Markt, overlooked by windowed cliffs of many-storied houses, with the great unfinished Gothic tower of the Cathedral of Our Lady reaching into the sky above the rooftops? How could he render such scenes without being overwhelmed by the sheer teeming multiplicity and variety of it all?

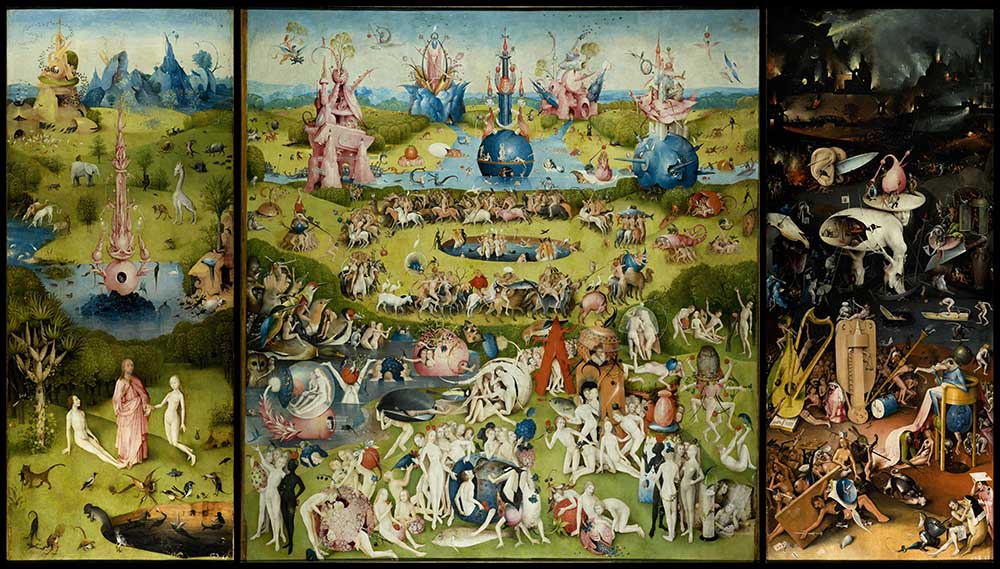

It was now that Bruegel discovered the work of another Dutch artist who seemed to have been similarly overawed by life in much the same way as he himself now felt. Yet somehow this artist, who had died just a decade or so before Bruegel’s birth, had managed to express his feelings—at the same time conveying a facsimile of the jumbled life and the discombobulated spirits of both himself and the souls around him. This artist was Hieronymus Bosch, whose crammed canvases—such as his highly charged and ambiguous triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights—conveyed everything from the carnival-esque to the grotesque, to such an extent that it was frequently difficult to separate the two. Here, in many ways, was Heaven, Purgatory, and Hell—an utterly medieval conception of the afterlife which awaited all souls, yet conveyed in realistic detail; a life in death where reality as we know it has been swirled and sliced into a dreamlike posthumous existence. Here was the world as it would be inhabited in the years to come by the likes of Faust, Frankenstein, Dracula, and their multifarious descendants and dreamers.

The modern analyst Julian Horx captures Bruegel’s conundrum when faced with Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights—the condition which faces us all:

The decision on how to engage with it falls on the observer. The act of engagement allows one to find one’s own narratives, representations of anxieties and occurrences familiar to them. The observer is trusted to navigate the chaos of the painting, and by extension the overwhelming complexity of its source material on their own terms.

Bruegel was initially overwhelmed by Bosch’s vision of chaos, and it would take him many years before he learned how to navigate such overwhelming complexity on his own terms.

Meanwhile, at the age of twenty-six he qualified as a member of the Guild of Saint Luke (the painters’ guild) in Antwerp. He was now a fully-fledged and independent artist. He at once set out on an adventurous journey across Europe, passing through France and crossing the Alps to Italy, where he ventured as far south as Sicily. While in southern Italy he witnessed the devastating effects of a Turkish raid on the city of Reggio Calabria. His drawing of this event captures the city on fire, as seen from a safe distance across the bay, with two tiny figures in the foreground throwing up their hands in horror at what they are witnessing. Bruegel here begins to grasp the full scope of landscape painting.

While in Rome, Bruegel briefly found employment as an assistant to the fifty-three-year-old Croatian artist Giulio Clovio, the finest miniaturist of his time. This enabled him to master the art of detail. And later, while passing through Florence, it seems likely that Bruegel was able to see, or study a copy of, Paolo Uccello’s Battle of San Romano, which he probably completed in the late 1440s. In the foreground, this work depicts lifelike fighting between mounted soldiers. But what seems to have caught Bruegel’s interest was Uccello’s depiction in the far background of a number of small distant figures moving amidst a countryside of hills and fields.

Bruegel was beginning to assemble the ingredients of his mature masterpieces. Alas, when he returned to Antwerp in 1555 after some four years in Italy he seems once again to have fallen under the influence of Bosch. His 1556 etching Big Fish Eat Little Fish depicts a monstrous fish stranded on the shore, spewing from its open mouth a cascade of smaller marine animals that it has swallowed. Meanwhile, a dwarfed human figure in a helmet slashes open its belly with a large serrated knife, causing a cascade of fishy grotesques to pour out onto the sand.

But Bruegel had not entirely forgotten what he learned in Italy. In the background one can see across a wide stretch of water the skyline of a distant city, whose church tower is recognizable as that of Antwerp. And behind the big fish, on the left of the painting, is a fishermen’s hut with large gutted fishes hanging from the branches of a tree. There is also a Bosch-like figure—half-human, half-fish—carrying off a smaller fish in its mouth.

In 1563 Bruegel was engaged to be married to Mayken Coecke, the daughter of his former apprentice-master Pieter. Bruegel now moved to Brussels at the insistence of his future mother-in-law, who had learned that he had formed a liaison with a local servant girl.

However, despite this move, Bruegel would remain in close contact with the Antwerp publisher Hieronymus Cock, who ran the printing presses and distribution network of prints known as Aux Quatre Vents (To the Four Winds). As its name suggests, this firm had widespread international contacts, and would play a major role in disseminating copies of Bruegel’s drawings and etchings throughout northern Europe. More importantly, Bruegel was now entering the period during which he would produce his best-known paintings.

Many of Bruegel’s masterpieces were produced against a background of political turbulence. Antwerp may have been the commercial hub of the Netherlands, but Brussels was the political capital—the center of its regional government within the Holy Roman Empire.

By now the situation in this far-flung Europe-wide empire was beginning to undergo a transformation, largely owing to the declining health of the emperor. Charles V had chosen to establish his main residence in Spain now that his family connections had led to him inheriting the Spanish crown. By this time, the Habsburg family had spread far and wide over Europe, and interbreeding in the family in order to retain dynastic power was beginning to have debilitating genetic effects. Most notably, Charles V had inherited the famous overlapping “Habsburg Jaw.”

Owing to increasing ill-health, Charles V felt obliged to divest himself of some of the territories over which he ruled. In 1555, the emperor appeared at a public ceremony held at the Palace of Coudenberg in Brussels. With tears streaming down his face, and forced to lean on his adviser William the Silent, or William of Orange, for support, Charles V announced what became known as the Abdications of Brussels. This ongoing process gradually divided the Habsburg Empire into the Spanish line and the Austro-German succession. One result of this was that Charles V’s son became King Philip II of Spain and Lord of the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands. Philip II was determined to stamp out Protestantism, which had already taken a strong hold in many parts of the Netherlands, especially in the northern provinces. A rumor spread amongst the Protestants that he was planning to introduce the Spanish Inquisition, which in 1566 provoked a revolt led by the Calvinist William the Silent. The revolt led to the Eighty Years’ War, during which the Protestant northern provinces of the Netherlands gradually separated from the southern provinces. This division would eventually result in the establishment of the Dutch Republic (loosely modern Holland) and the Spanish Netherlands (loosely modern Belgium and Luxembourg). Subsequently, the Dutch Republic would enter its “Golden Age,” during which Dutch traders established an overseas empire from the Americas to Indonesia, while the sciences flourished in the homeland as never before.

Although the ructions of the Eighty Years’ War did not involve continuous fighting—there was even a Twelve Years’ Truce signed in 1609—they provided a troubled background to the later years of Bruegel’s life.

The mature masterpieces which Bruegel would produce during the last years of his life barely hint at the political turmoil unfolding around him. Yet the clues are there if one looks hard enough. His several panoramic winter scenes paint an evocative picture of countryside under snow; these are as spectacular as they are chilling. His scenes of the snow-blanketed countryside may be magnificent in their vision of bleakness, but they do not depict a happy or an easy way of life. (The Little Ice Age, which affected Europe to a more or less degree between 1300 and 1800, was approaching its most severe stage. The depiction of winter scenes became a genre at this time, but the paintings of Bruegel outshone all others in their atmospheric intensity.)

Other paintings by Bruegel during these years depict a wide range of disparate subjects, yet still manage to convey the troubled zeitgeist. Perhaps the most blatant of these is The Blind Leading the Blind, which is a nightmarish scene of medieval misery, yet its peasant faces and the literal helplessness of its subjects are rendered with a Renaissance realism and composition that conveys all too well its proverbial content. Here allegory and actuality are blended with supreme artistry. Even the comparative ease of the recumbent figures in his celebrated The Land of Cockaigne contains ominous Bosch-like images in the background. This is not just a clerk, a peasant and a soldier lying sprawled out in the afternoon countryside, snoozing after a pleasant bibulous lunch. The clerk’s eyes are open, his features frozen in a blank expression. Cockaigne is the mythical land of plenty and these supine figures are gluttons overcome by sloth; it is a vision of spiritual emptiness.

Similarly, Bruegel’s brilliantly realized scene in The Peasant Wedding, for all its witty observation and feasting plenty, is hardly a joyous spectacle. The plethora of superbly characterized individual figures feature mainly dour faces that are all but expressionless.

In the last years of his life Bruegel would paint two versions of The Tower of Babel. These depict vast intricate constructions whose incompleteness enables us to gain an insight into the complex engineering involved, and which were inspired by the ruins of the Colosseum—which Bruegel had seen while in Rome during his twenties. Indeed, he is known to have painted an earlier miniature version of this scene while he was working for the maestro Giulio Clovio, though this is now lost. Even so, the larger versions contain a miniaturist’s eye for detail—from the tiny silhouettes of the builders against the sky at the uppermost level, to the stonemasons bowing in servile reverence at the foot of the tower as they are approached by the visiting king and his entourage.

Pieter and Mayken Bruegel would have two sons, who both became artists. Pieter Brueghel the Younger would grow up to build a successful artistic career copying his father’s style (and in doing so increase his father’s reputation). His other son, Jan Breugel the Elder, would become an important artist in the Flemish Baroque style which flourished during the Dutch Golden Age.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder himself became old before his time. A self-portrait from 1565 when he was in his early forties depicts a somewhat scruffy bearded figure with an old man’s features. He would die just four years later, leaving his mother-in-law Mayken Coecke to instruct his sons in the art of painting. Mayken Coecke, who painted under the name of Mayken Verhulst, is known to have been a highly skilled artist in her own right, though her works have yet to be reliably identified.

And what of Bruegel the Elder’s lasting reputation? The great sixteenth-century Italian historian of the Renaissance, Giorgio Vasari—whose Lives of the Artists bring so much of this period to life—barely acknowledges the northern Renaissance. Though he does find time to denigrate Bruegel as “essentially a comic successor to Hieronymus Bosch.” During Bruegel’s lifetime he achieved renown largely as a genre painter of peasant scenes—for the most part more popular with the emergent merchant class than with connoisseurs and art critics. During the century after his death he influenced a number of less-talented artists who attempted to imitate him; yet at the same time his true talent was recognized by the Austrian Habsburg emperor Rudolf II and the great Baroque artist Peter Paul Rubens (who collected a dozen of his paintings).

Reprinted with permission from The Other Renaissance: From Copernicus to Shakespeare: How the Renaissance in Northern Europe Transformed the World by Paul Strathern, published by Pegasus Books. © 2023 by Paul Strathern. All rights reserved.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/ZmEYizw

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.