Omar Casimire dreamed of a flood a year before Hurricane Katrina arrived. The day after the levies broke, as he paddled a salvaged boat through the deluge burying New Orleans East, using a broken board as an oar, the vision resurfaced as déjà vu.

With a small digital camera, he photographed the dreamscape that now appeared in the world before him: familiar street signs barely clearing unfamiliar reservoirs. He took pictures as he watched the waters rise from a room in the Super 8 Hotel on Chef Menteur Highway, east of the city’s Industrial Canal and south of Lake Pontchartrain—both breached—where he’d needed to sign a liability waiver to stay. As he told it in a poem he wrote later, “The Super 8 roof started to peel like a Plaquemines Parish orange.”

The need to preserve what he saw followed him like a phantom. He took photographs as he sought refuge in the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center—a shelter of last resort, like the infamous Superdome—where an estimated twenty-five thousand people awaited supplies and evacuation, languishing for days. He documented a baby’s first steps amid the exhausted crowd; National Guardsmen resting in wheelchairs on a nearby street, rifles between their legs.

One morning in late January last year, the plastic-sheathed pages of what Omar calls his Katrina List sat in an open binder in my lap, like a holy book. It was one volume of a collection of thousands of names, phone numbers, and signatures of survivors of the storm and its aftermath. I was seated in the front room of his home on the ground floor of a two-story shotgun house on Cleveland Avenue, a notoriously flood-prone area of Mid-City that, on one rainy day in 2017, had left Omar knee-deep in water inside.

We were surrounded by a maze of folding tables, chairs, and couches draped in kente cloth. In the center of the room sat a four-by-four-foot metal cage that had been used by a search and rescue team to airlift people from the roofs of inundated houses after Katrina. Every inch of the wall space around us was occupied, covered with artwork depicting the storm’s ravages, and with Omar’s photos. On one wall hung a large tarp affixed with handwritten accounts by survivors and aid workers: Triaging a nursing home patient who handed me a wet plastic grocery store bag & said “This is everything I have left.”

Omar, a spry seventy-one, and dressed in white slacks and a white button-down, called this place the Katrina National Memorial Foundation. It was a house museum, as spaces like this are known in New Orleans—an installation of local and personal memory, sometimes art and culture, in a private home, open to the public and most often run by a black elder.

I came to the house museums through my friend Don Edwards, a gray-bearded griot who, on most days, could be found spinning tales in front of Flora café in the Marigny, where I first met him nine years ago. I lived in Louisiana as a teenager, and am now a seasonal resident of New Orleans, returning in the sweltering summers and fickle winters. Whenever I’m in town, I find Don at Flora, under the banana leaves, smoking the Pyramid cigarettes he’ll only buy at a certain liquor store in Chalmette, a suburb to the east. And he always greets me by saying, “I got someone I want you to meet.” Soon we’re on our way in his white utility van, its mysterious contents rattling and rolling in the back as we fly over potholes. It was Don who introduced me to Omar, and to many other house museum proprietors—mostly men like him: charismatic and black, over seventy, and prone to winding stories.

Each time I come back to New Orleans, I become more aware of the responsibilities of memory work. In the past two years, several of the house museum proprietors have died. I returned this time to document the house museums while they still existed, and to see the curators who remained, men who had become my friends—to listen to the stories of elders who had survived Katrina, the COVID-19 pandemic, the difficult years long before, and the precarious years in between.

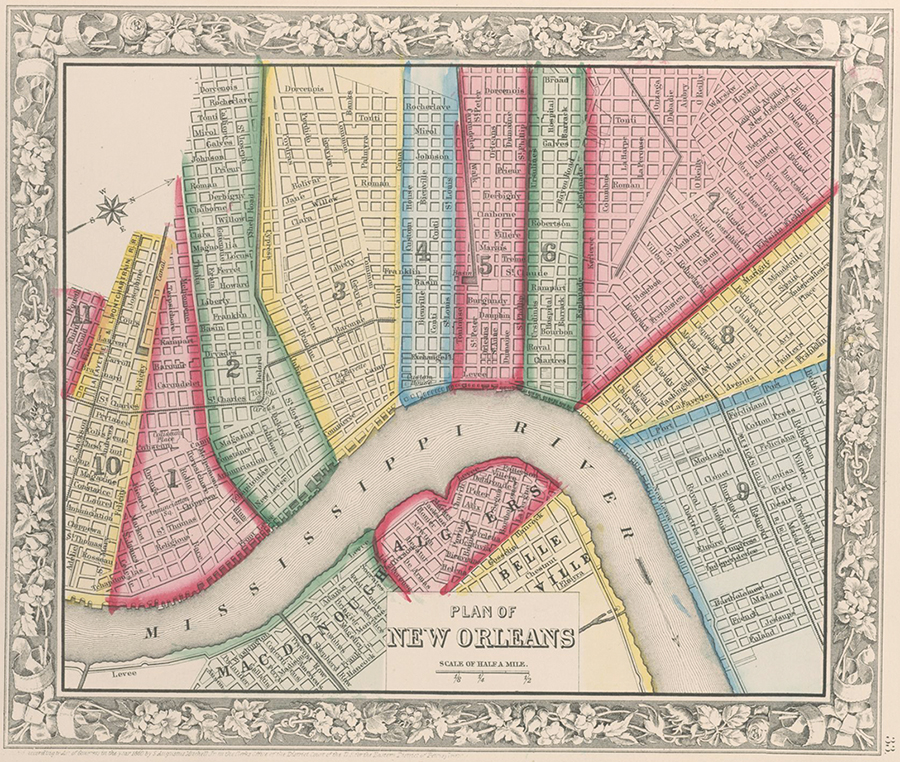

A map of New Orleans, 1863. Courtesy New York Public Library

Omar’s museum, divided from his living space by a curtain of wooden beads, is dedicated to the storm and to the dream of a future, grander memorial for its victims. Spread along one wall were blueprints, plans drawn up by his ex-wife, an architect, for the shrine of twisting glass and steel he aspires to build, its footprint the shape of a spinning hurricane. Less than two miles down the road, on Canal Street, was the city’s $1.2 million official memorial for the nearly twelve hundred Louisiana residents who died in the storm—a series of marble mausoleums containing the remains of the unknown dead, and engraved with the names of the known. “All that money, and you can barely even read the names on those big old stones,” Omar said. “And they stole my design!” The monument’s walkway resembles a cyclone from above. Omar had sent a cease and desist letter to the mayor when it was constructed in 2008—he handed me a hefty three-ring binder to show me a copy. “I call this my Blood Book,” he said. Inside were dozens of missives: sent to the IRS, and to New Orleans city planners, citing sundry broken promises, especially regarding the city’s sites of public history.

Omar flitted around the crowded room like a hummingbird, conjuring more documents and photo albums from overflowing drawers and shelves crammed with books about the storm—titles like 1 Dead in Attic, and Not Just the Levees Broke. The inauguration of Joe Biden played quietly on a television perched amid the papers on his desk. “Do you remember Barack Obama’s inauguration?” he asked wistfully. “I was there!” He’d arrived a week early and stayed in what he called his “executive suite”—a van parked at a rest stop outside of D.C. He handed me a commemorative talking pen, still in its plastic cover, that blasted a line from Obama’s 2008 election night acceptance speech: “Change has come to America!” I remembered it of course—the feeling that things would be different.

Omar told me that he’d planned to use his Katrina List to sue the government. “They abandoned us,” he said. Like many of the tens of thousands of people evacuated from New Orleans after the storm, he was flown out of state with no choice as to where he might be sent, and he arrived at Fort Chaffee, a military base in Arkansas that had housed Vietnamese refugees in the Seventies and Cuban refugees in the Eighties. “Some people don’t like to be called refugees,” he said. “But I tell them, ‘You was a refugee.’ They treated us like cattle.” He spent his days at Fort Chaffee watching news coverage of the flood and searching the internet for information on his home and his family. That was how he discovered that his mother, Louise Thecla Jones-Casimire, had died after being moved out of her nursing home, which had lost power. A colorized photograph of Louise as a young woman in the Forties sat on a table nearby, her lips and cheeks the same powder pink.

After Katrina, traumas like Omar’s became one of the most recognizable elements of New Orleans identity, alongside jazz and Bourbon Street, and the city was met with a wave of appetite for black suffering. Local tour companies, which had long offered “ghost tours” of the French Quarter and shepherded visitors around the grand homes of the Garden District, added “Katrina tours,” delivering out-of-towners to hard-hit neighborhoods to gawk at the destruction from the safety of air-conditioned buses. This hunger for devastation has remained and in part remade the city. It’s there in the shops on Decatur Street selling T-shirts that read new orleans: you have to be tough to live here over an image of the Superdome and a handgun. It’s there in the eyes of tourists when they ask what exactly happened during the flood.

That’s a question Omar never answers directly. He speaks circuitously, often recounting the history of New Orleans, its three hundred years of European, African, and Asian migration. “Napoleon needed the money,” he told me, explaining the Louisiana Purchase, “ ’cause he was fighting our grandparents in Haiti, and he didn’t know they could fight.” Omar had figured out the Caribbean origins of my last name, and determined that we were likely cousins. “You know who this is?” he asked, pointing to a pin in the top button of his shirt, a tiny photograph of a light-skinned woman with thick black hair. I recognized her as Henriette Delille, a nineteenth-century New Orleanian nun, and the first black American woman to be considered for sainthood by the Catholic Church. “That’s my great-great-great-aunt by marriage,” he said proudly, producing yet another binder, this one full of marriage licenses, death certificates, and other records printed from the Louisiana State Archives and Ancestry.com.

Omar had long sought formal recognition of his place in New Orleanian, Louisianan, and American sagas, especially through entrée into historical societies, and he pulled the Blood Book out again to show me letters documenting his battles. He’d recently proved that his seventh great-grandfather was a Frenchman who fought alongside the American colonists in the war for independence, earning Omar a place as the only black member of the New Orleans chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution. But over the past three years he’d twice been denied membership in the General Society of the War of 1812. He turned the book’s pages to certified copies of the records he’d sent the organization, substantiating that nine of his ancestors had fought in the war. He believed that the majority-white group would rather not acknowledge his heritage. “They don’t want me to join because they know I’m kin to some of them,” he said. As he waited for a response to his most recent appeal, he’d started an alternative association: the Free People of Color Battle of New Orleans War of 1812 Society. So far, he was the only member.

By the end of the visit, I was left holding everything Omar had thrust into my hands—the Katrina List, the photo albums, the Blood Book, the talking Obama pen. I didn’t want to set any of it down, for fear of implying that any piece was unimportant.

As I balanced these items in my arms, Omar led me to an altar, tucked away in a far corner of the room. On a cloth-covered table sat Hindu prayer cards, a brass bell, a peacock feather, a small bottle of Barefoot wine, and photos of spirits related and unrelated: famous yogis, an aunt who’d passed away the year before, and Omar’s youngest daughter, Asha, who’d passed in 2007 at twenty years old. “She had a weak heart,” he said. A note written just days before she died rested against her wedding portrait: I pray for health, wealth, happiness, and love now and forever for myself and the world.

The altar was like the museum—or rather, the museum like the altar. It had the same accretive logic, the same impulse to collect material shards left behind, and to say, “This was life.” Or, this is life. “What do you think?” Omar asked. “Does it need anything?”

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/Aw7e6j8

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.