I know it is a common stereotype for an old guy to complain about how good the kids have it today. I, however, will take a little different approach: We have it so much better today when it comes to access to information than we did even a few decades ago. Imagine if I asked you the following questions:

- Where can you have a custom Peltier device built?

- What is the safest chemical to use when etching glass?

- What does an LM1812 IC do?

- Who sells AWG 12 wire with Teflon insulation?

You could probably answer all of these trivially with a quick query on your favorite search engine. But it hasn’t always been that way. In the old days, we had to make friends with three key people: the reference librarian, the vendor representative, and the old guy who seemed to know everything. In roughly that order.

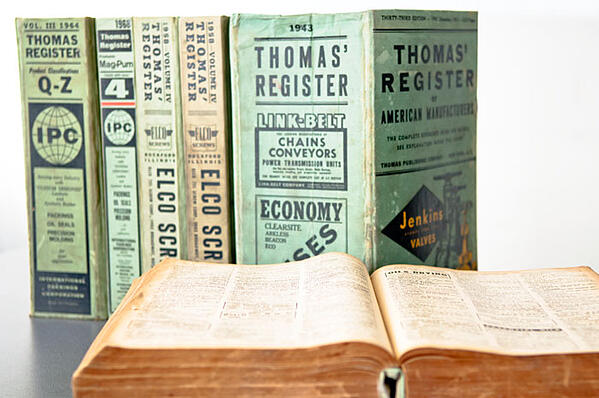

Thomas’ Register

Back in the day, any good library had a tremendous set of green books known as the Thomas’ Register. These sort of still exist, but as a specialized search engine called ThomasNet. The books date back to 1898, but in the 1970s and 1980s, they contained 34 huge volumes. They were essentially a Yellow Pages for industry. If you wanted to know who sold fiber washers, there was a list in the register. Epoxy sealing compounds? Check the big green books.

What always struck me when browsing through the Register is that someone woke up one morning and thought, “I should start a business selling plastic pipe caps.” You can only assume there was some logical progression that led to that decision, but you have to wonder.

Kudos, though, to Thomas for being nimble enough to move to digital even though the company is over a century old.

The Chemical Formulary

The Register was good if you wanted to buy something, but what if you wanted to make something chemically? Then you went looking for The Chemical Formulary, a set of 10 or 11 books that are still available in some form.

For example, suppose you wanted to start building electrolytic capacitors. In the 1940s, those were condensers, and the Formulary shows several compounds along with British patent numbers. Some of the recipes were quite specific. Some, like this electrolyte one, is very brief:

Liquid Dielectric

British Patent 493,961

Chlorinated Diphenyl (60% chlorine) 2 lb.

Trichlorobenzol 2 lb.

Tetrachlorobenzol 1 lb.

There’s no discussion about what the properties of the compound would be or why you’d use it over the other included recipe which called for ethylene glycol, boric acid, and ammonia. Don’t expect a material safety data sheet, either.

Yet some of the formulae are more specific. A rectifier element calls out specific instructions for oxidizing copper plates. Some of the entries aren’t even really compounds. One entry is about detecting forged documents using a few chemicals, but it wasn’t exactly clear how it would indicate a forgery. It is funny how the entries range from highly technical (zinc etching and light-sensitive emulsions) to quite pedestrian (how to remove alcohol spots from polished furniture).

[Styropyro] tested a few of the recipes for things like fireproofing and a reusable match. You can see his video experiments, below. We were suspicious of the contraceptive jelly formula and the compound you were supposed to smoke in a pipe to relieve asthma.

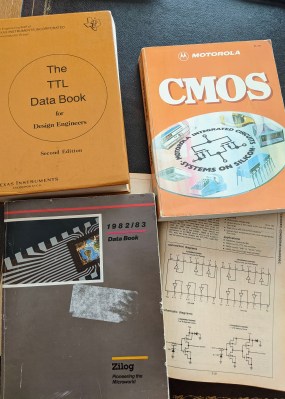

Data Books

If you wanted to find out about a particular IC in the old days, the best thing to do was to find the manufacturer’s data book. If you were in a school or a company, there might be what you wanted in the library. Otherwise, you’d have to beg or borrow a copy from the manufacturer. These were prized possessions and were rarely sent by mail because of the expense.

You’d usually get these from sales reps who wanted to sell you the parts in the book. If you got a new edition of, say, a TI databook, you might generously pass down your old copy to a junior person. It was more common to order from the company just a particular datasheet for a specific part, but that was difficult to browse through if you were just trying to get ideas without a specific part in mind. Some datasheets were works of art, with example circuits and detailed explanations about the device. There were also books for discrete components that would describe characteristics of, say, transistors, and provide cross-reference tables so you could replace one maker’s transistor with another.

You could buy some databooks at stores like Radio Shack which had, at least, some books from TI and National Semiconductor you could purchase. Catalogs were more available, and they had some information, too. However, it was rare for a catalog to have as much data as a proper datasheet or databook. There was also a trend for data to show up on microfiche. If you don’t remember that technology, it was essentially small filmstrip organized in an index card-like format. A reader could magnify the page you wanted to read on a screen.

You could buy some databooks at stores like Radio Shack which had, at least, some books from TI and National Semiconductor you could purchase. Catalogs were more available, and they had some information, too. However, it was rare for a catalog to have as much data as a proper datasheet or databook. There was also a trend for data to show up on microfiche. If you don’t remember that technology, it was essentially small filmstrip organized in an index card-like format. A reader could magnify the page you wanted to read on a screen.

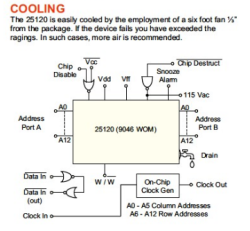

One prized datasheet was for the Signetics 25120 Write Only Memory. This fictitious device had arguably the most famous datasheet of all the spoof datasheets ever created. The schematic diagram showed a faucet as the “sink” just to give you a flavor for how silly it was. There were other spoof sheets, though, including the Zener-enhanced dark-emitting diode.

IC and EE Masters

The problem with data books is they typically covered one vendor. Sure, a TI 7474 was probably just like a National 7474, but there could be small differences. But the real problem was the many parts that only had one or two sources. If you didn’t have the right data book, you’d probably never hear of that part. That’s where the IC Master came in.

If there was ever a book that should have been in volumes, it was the IC Master. The thing was huge like an Oxford English Dictionary. It would contain just about every datasheet from every vendor at the time of its publication. These were not cheap, but they were worth it. The only problem is the vendor’s databook probably included application notes and other information that you might not get in the IC Master. But you still would at least know a part existed and could research it further.

You can find some PDFs of the giant books online. The 1979 edition takes a while to load with nearly 2,400 pages!

For everything other than ICs, there was the EE Master. This was another big book, sometimes in a few volumes, that was like the Thomas’ Register, but only for electronic components. That means it could be more detailed and if you were looking for something even vaguely electronic, this could be your first stop.

The Good Old Days?

Some people fondly remember the good old days. Not me. Give me an internet search any day of the week over poring through out of date books. Even catalogs are better since nearly all the major websites now let you search and filter through components. Many will even point out ways to save money with equivalent parts or by exploiting quantity price breaks.

While I appreciate the feel of a paper book in my hands, I don’t want to go back to those days. It makes you wonder what will be around 50 years from now, though. Will you go to the QuantumMart VR store and tell the AI what you are trying to do and let it produce a design for you? Who knows? But just as we couldn’t imagine replacing our beloved data books, it is difficult to see what will replace the tools we use today.

Photo Credit: Thanks to [Tom N3LLL] for the picture of his fine collection of reference books.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/LKVWPlt

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.