Let’s be honest. When you read this post’s title, you thought it was obvious. Yet, most people don’t follow this simple piece of advice. You know that too, and that’s probably what led you here.

What you don’t know is why so many people won’t finish what they start and how to illustrate and quantify the impact of unfinished work. That’s what I’ll explain in this post.

First, I’ll expound on the reasons why finishing one piece of work before starting the next makes products better, cycle times shorter, and teams more productive.

Then, I’ll expose why some teams choose to work on multiple tasks concurrently despite that approach being suboptimal most of the time. In this section, I’ll also explain when to batch tasks, when not to, and what you should do instead.

Finally, I’ll use a few Monte Carlo simulations and cumulative flow diagrams to demonstrate how unfinished work makes teams unpredictable — statistically speaking.

At the end of this post, I have included a small summary for you to paste on Slack or Microsoft Teams and convince your team to stop starting and start finishing.

If you’re reading on a phone, click images to expand them.

How finishing what you start increases productivity

I like burgers. Do you? I don’t like them when they’re cold, though, and it makes me unhappy to wait too long for one.

When I’m the only person at the burger shop, it’s not a challenge for its cooks to assemble a burger quickly and for waiters to deliver it to me while it’s still hot.

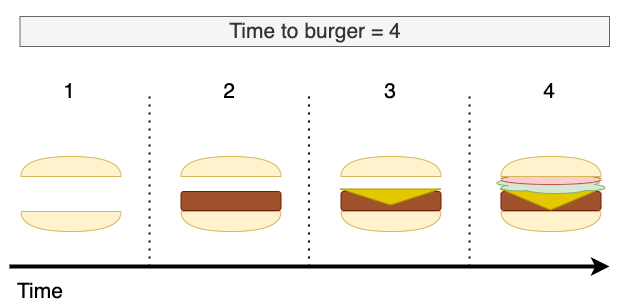

Here’s what happens when I’m the only person in the shop.

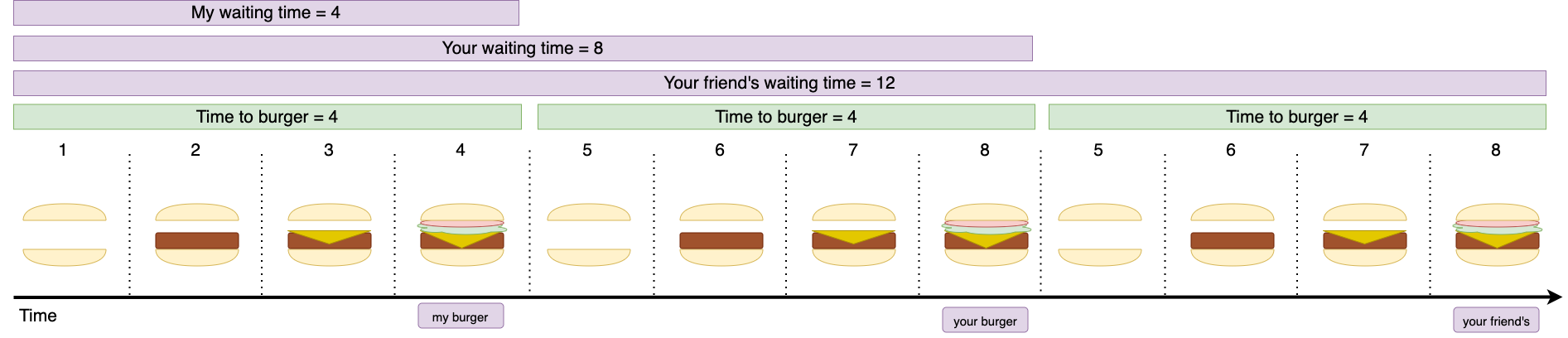

In this case, considering each burger demands four steps of preparation, and each step takes one minute, my burger gets to me in four minutes.

When you arrive at this burger shop, the cook’s job gets a bit more difficult. Now, they have to choose between preparing our burgers concurrently or one at a time (serially).

To illustrate these approaches, I’ll assume there’s a single cook and that they can only prepare one burger at a time. We’ll revisit this assumption later. For now, bear with me.

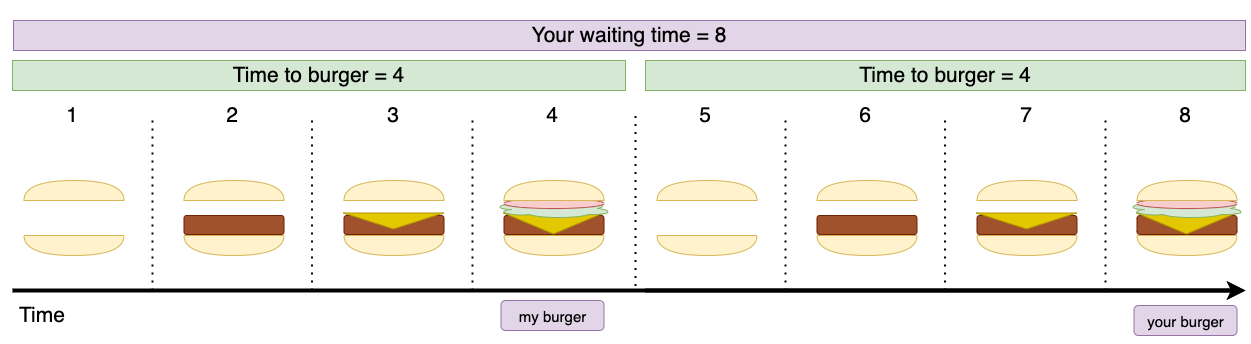

First, let’s see what happens when the cook prepares one burger at a time.

Assuming I ordered only a bit before you, my burger still takes four minutes. Yours, however, takes eight.

Now, let’s compare the serial to the concurrent approach. In the image below, you’ll see what happens when the cook tries to prepare our burgers concurrently.

This time, you still had to wait the same amount of time for your burger, but I’ve had to wait almost twice as long for mine! Outrageous.

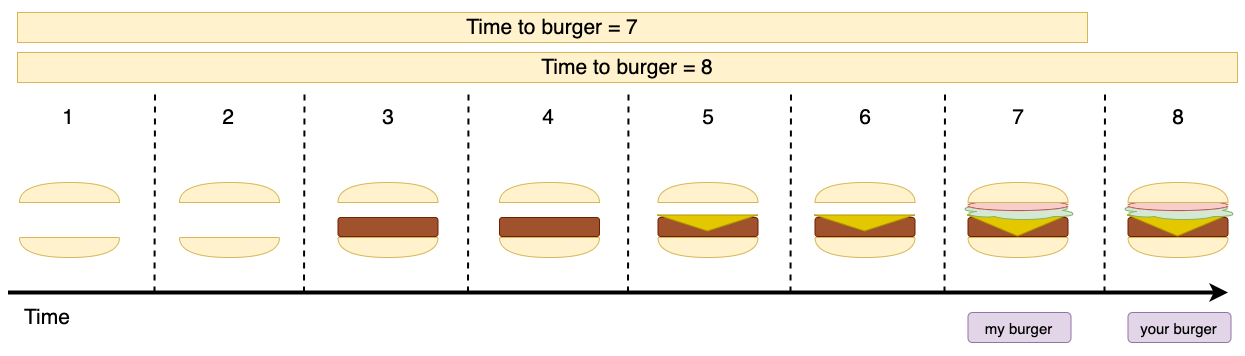

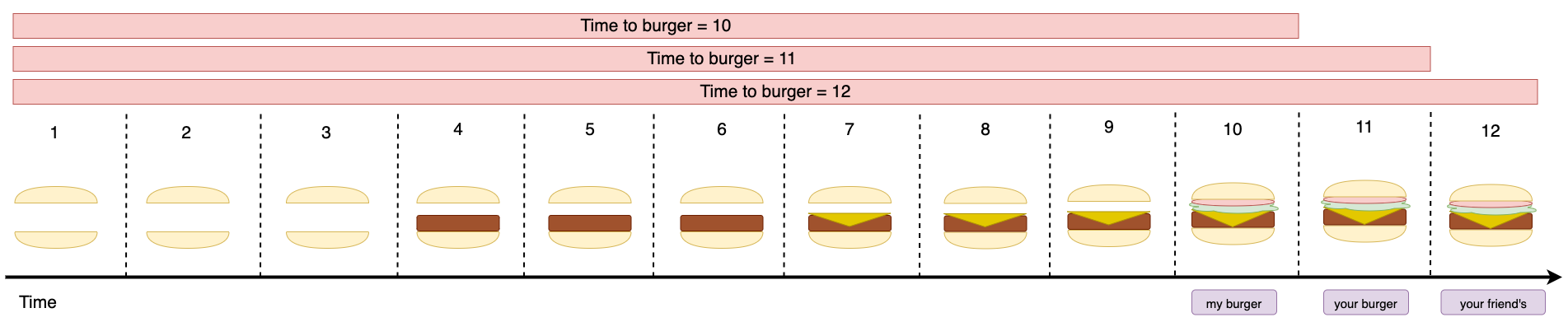

To make matters worse, let me show what happens if a friend of yours comes in, places an order, and the cook decides to take the same shortsighted approach to burger-making.

In this scenario, I took ten minutes to taste my burger, and you took twelve. Thanks to your friend, I had to wait an extra six minutes, and you had to wait for an extra three.

Such a disappointing burger-preparing performance demands vigorous action to be taken.

Personally, I’d prefer to educate the cook rather than kick you and your friend out of the shop because I believe every hard-working engineer deserves a succulent burger on a Friday night.

Here’s what we’ll do. First, we’ll illustrate what would’ve happened had the cook decided to prepare each of our burgers in series. Then, we’ll enter the kitchen, hand them the schematics, and explain the optimal approach.

Come join my table, grab a pen, and let’s get drawing.

As our drawing shows, had the cook prepared our three burgers in series, you and I would have had to wait the same amount of time for our burgers as before — 4 and 8 minutes. Your friend’s burger would still have taken twelve minutes, but that’s what they deserve for being late for dinner.

Now, before showing our drawing to the cook, let’s take a moment to compare burger-making with the equally noble activity of software development.

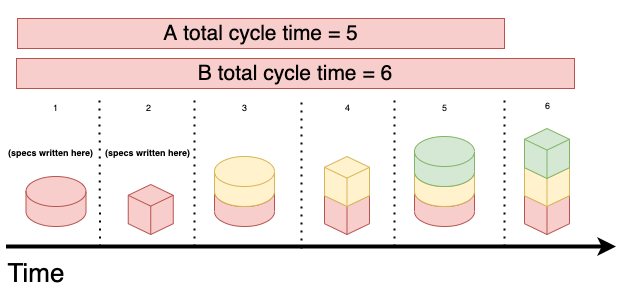

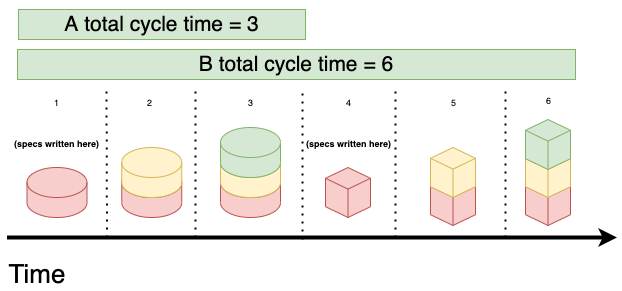

Imagine you have features A and B in your backlog, for example.

If each feature takes three units of time to deliver, working on them in parallel makes A take two units of time longer to deliver than it would have taken had you finished it before starting B.

Furthermore, working on these features concurrently demands B’s specifications to be written earlier than they would have been otherwise.

On the other hand, if you finish A before starting B, you’ll deliver A earlier, and you’ll buy yourself more time to work on B’s specifications. During that time, you can collect more information to boost B’s chance of success.

As you can see, in the software industry, both tasks take longer to deliver whenever you start a new feature before finishing the first. Moreover, the first task will be delivered later than it could have been.

Furthermore, the likelihood of the second feature succeeding is smaller because you were working on top of specifications that were older than they could have been. Had you waited a bit longer, you’d have had more time to digest customer feedback and incorporate new information into the second feature’s specification.

That’s what just-in-time means: instead of starting each feature as early as possible, you start it as late as you can afford to, and incorporate as much feedback and information into the spec in the meantime.

This same effect happens when a critical bug appears. As I’ve previously explained, such urgent work stops you from finishing your current task, delays it, and causes all other tasks in progress to take longer on average.

We can summarise this behaviour using Little’s Law, which, when expressed in terms of throughput (deliveries per unit of time), looks like this:

As I’ve explained using the burger shop example, and as Little’s Law dictates, cycle times elongate when work in progress increases and throughput remains the same. It’s a straightforward mathematical fact. Nonetheless, many managers are unaware of it.

Despite the simple mathematics, when some managers see that work is taking longer to finish, they start more work hoping that starting tasks earlier causes them to finish earlier. This attitude leads to the exact opposite of the result they’d like to achieve: it increases cycle times.

If you wish to keep cycle-times low, you should limit work in progress.

You can argue with me, your team, or your manager as much as you want, but you can’t argue with mathematics. Limit work in progress.

The cost of context switching

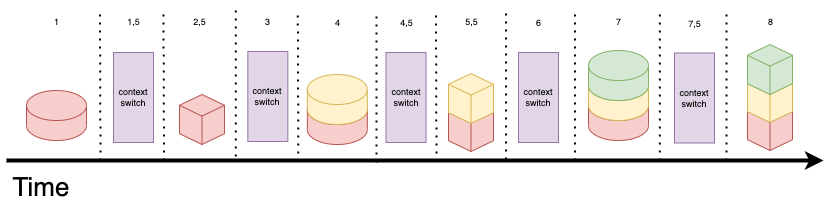

There’s yet a third crucial aspect to consider in the world of software development: the cost of context switching.

When preparing burgers, it’s effortless to shift from working on one burger to another. When writing software, on the other hand, context-switching incurs a high cost.

Working on tasks concurrently delays their cycle times not only because of the interleaving activities but also because every time an engineer has to switch context, they take more time to get back into a “flow state”.

Here’s a more accurate representation of what happens when working on software development tasks concurrently:

Enough talking. Let’s bring our plan into the kitchen.

When to start without having finished

You and I delve into the kitchen with our drawing in our hands, the power of mathematics under our arms and tell the cook:

“Hey, look, here’s why you should prepare one burger at a time” *points to drawing*

The cook seems abhorred and goes on to explain:

No matter how rare you like your patties, they all take significant time to prepare.

It’s quicker for me to prepare them in larger batches than to wait for one patty to be ready before I toss another on the grill.

The cook has a point. Neither you nor I know anything about the craft of burger-making; how could we expect to be right?

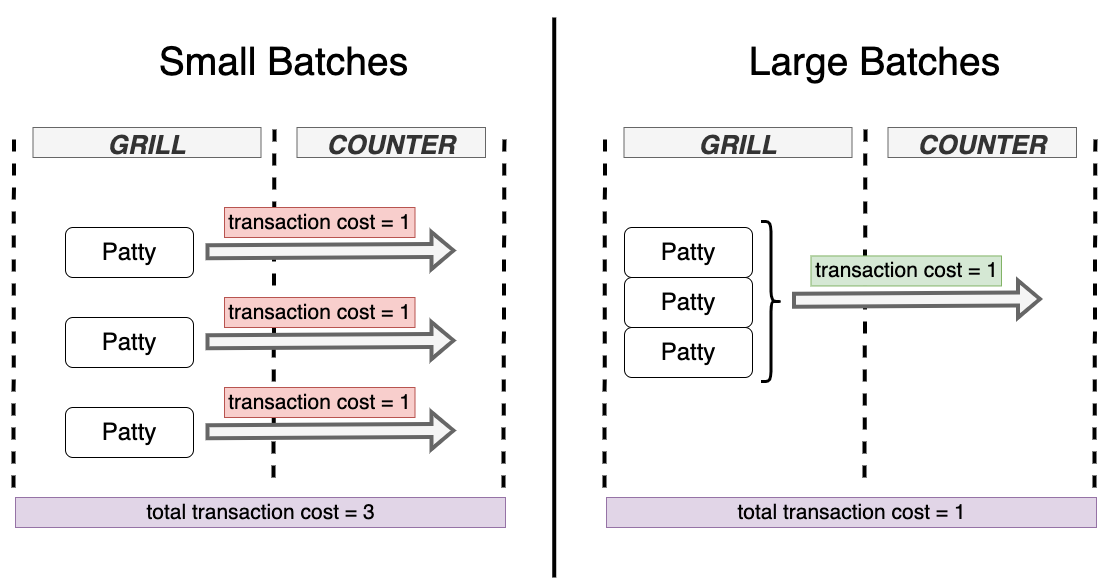

Nevertheless, there’s a lesson to be taught here — one about batch sizes and transaction costs.

Whenever it’s expensive to move a work product, in this case, a patty, from one stage of the production process to the next, that transition will happen less often so that you can pay the transaction cost only once by moving multiple items at a time.

That’s why you don’t buy a single egg whenever you go to the supermarket. Going to the supermarket has a significant transaction cost, so you purchase eggs in larger batches. In fact, the farther from your home the supermarket is, the more likely it is for the batch of eggs you bring home to be larger.

It’s only when the cost of keeping the patties in the grill exceeds the cost of sending them to the counter that the cook will do so.

To summarise: whenever a transaction’s cost goes up, that transaction happens less frequently.

Furthermore, if the cost of holding items at a particular stage of the process is lower than the cost of pushing those items forward, it’s better to hold them.

That’s also the reason why Martin Fowler and Jez Humble advocate that “if something is painful, you should do it more often”, especially when it comes to deploying software. If you’re forced to do something often, you’ll naturally gravitate towards decreasing the cost of doing it.

You can notice the same effect happens with automated tests. If you have to manually test your software for a few hours before you ship it, you’ll hold changes for longer and test larger batches at once.

In the software industry, there are several problems with large batch transferrals:

- They delay feedback because features take longer to get to customers

- They make it more difficult to trace bugs because the delta between each version is larger

- They increase the overhead of change management because they make versioning and automatic rollbacks more difficult to do

These problems exponentially increase the costs of holding software tasks as opposed to pushing them forward.

The reason many people fail to acknowledge and act upon transaction costs in the software industry is that they compare software — a design process — to manufacturing processes.

In manufacturing, the cost of holding pieces in a factory is linear. The holding cost for a piece is just the cost of keeping it in storage multiplied by the number of days it will be there. On the other hand, in software development, when holding a particular piece of work, you’ll experience a negative compounding effect due to the lack of feeback, the larger deltas between versions, and the overall harm to the overall system reliability.

Now that we understand the burger and the software variations of the problem, we can make a recommendation to both cooks and software engineers alike:

Reducing transaction costs enables small batches. Small batches, in turn, reduce average cycle times, diminish risk, and enhance reliability.

You should only start without having finished when transaction costs are high, and it wouldn’t make economic sense to spend time decreasing them, either because you have agreed to a particular delivery date or because you don’t have the capital to invest.

That said, I’d be careful to avoid falling into a situation where “you’re too busy draining the flood to be able to fix the leak”. The earlier you decrease transaction costs, the earlier you’ll be reaping the benefits from having done it.

How finishing what you start makes teams more predictable

Despite coming into the kitchen to offer unsolicited advice, you and I have become good friends with the cook. Now, it’s time for them to teach us a thing or two about how we can deliver software more predictably.

In the burger shop’s kitchen, there’s a limit to how many patties you can put on the grill. Furthermore, zero burgers are in progress at the end of the day. “These constraints allow me to provide burger-eaters with predictable delivery times”, — says the cook.

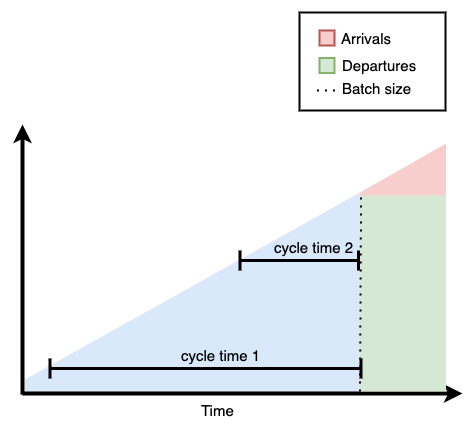

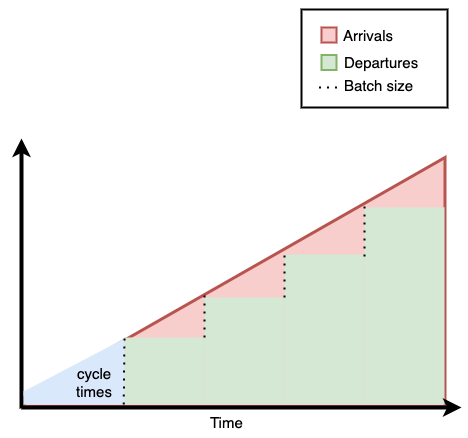

To understand why those constraints help the cook, let’s plot the burger shop’s arrivals and departures using a cumulative flow diagram.

First, let’s plot a cumulative flow diagram illustrating what happens when the cook prepares many burgers at once — a large batch.

As the diagram shows, a customer who arrives early waits for a long time for their burger, while a customer who comes later waits much less. In other words, there’s a significant amount of variability in the time customers have to wait until they get their burger — shown by the area in blue.

Now, let’s see what happens when the cook prepares fewer burgers at a time.

This time, a customer who arrived early doesn’t have to wait much longer than the customer who came later. As shown by the area in blue, there’s less variability in the time it takes for customers to get burgers.

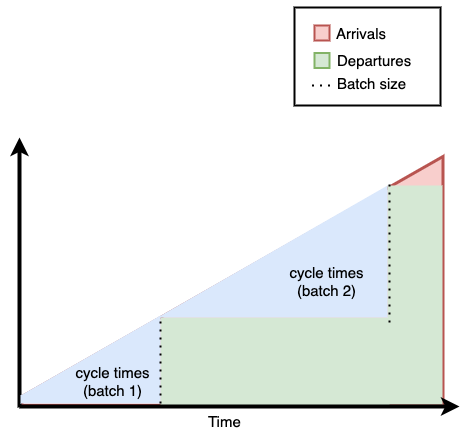

After looking at these two diagrams, we can conclude that the larger the batch size, the more variability there is in waiting times.

Additionally, if batch sizes vary, not only will the waiting time within a particular batch of customers be more variable, but also distinct batches of customers will see different waiting times. Customers who arrive earlier may see cycle times from 1 to 10 minutes, while customers who come later might see their burgers taking anywhere from 1 to 30 minutes, for example.

That’s why the cook mentioned it’s helpful to limit how many burgers they can fit on a grill: it makes batch sizes uniform.

The same principle is valid for software development. The larger your batch sizes — the more tasks you work on in parallel — the more variability in cycle times you will see.

In the software industry, however, we don’t have a “finite grill”. In other words, there’s no physical upper cap on how many tasks can be in progress at a time. Therefore, you must be adamant about creating work in progress limits yourself.

The lower you make WIP limits and stick to them, the less variability you’ll see in cycle times.

Besides making your cycle-times unpredictable, the lack of WIP limits will also impact your ability to do forecasts.

Imagine, for example, that your team tends to work on many tasks concurrently. In that case, most days they’ll split their attention between tasks. Then, there will be a day in which they’ll complete all those tasks, doing a large batch transferral.

Let’s simulate such a team assuming that their throughput over ten days looks like the following:

// Each item represents the number of tasks delivered that day

const TEN_DAY_THROUGHPUT = [ 0, 0, 0, 0, 5, 0, 0, 0, 5, 0 ];

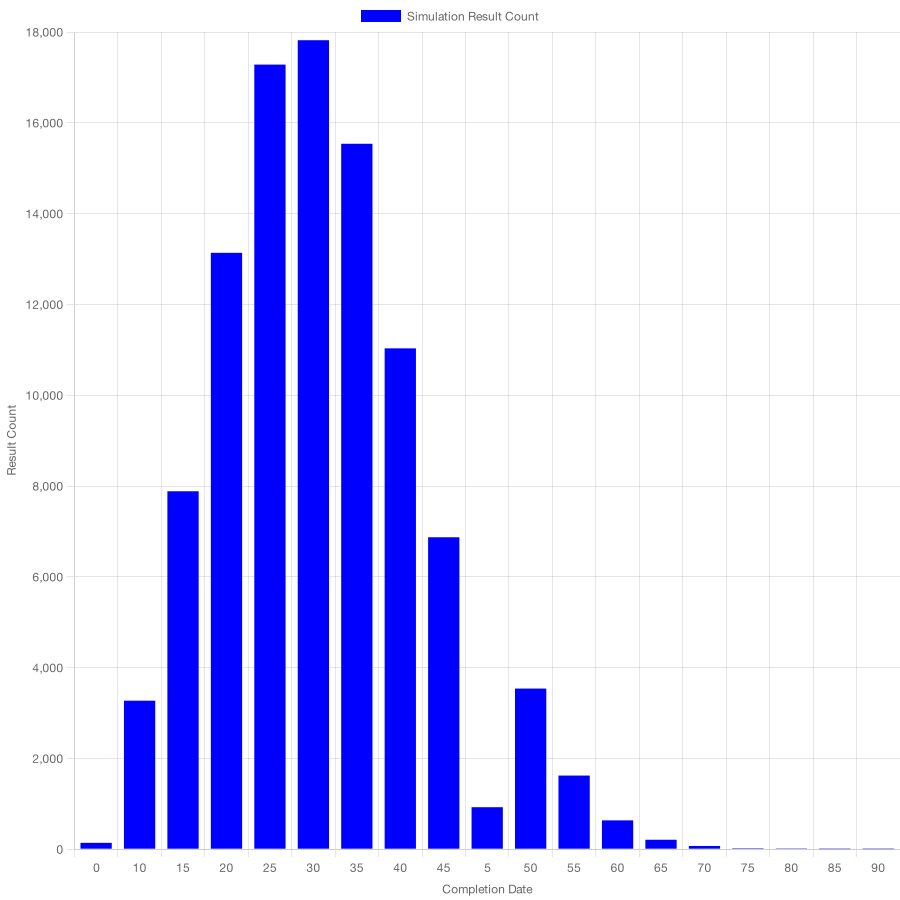

If we go ahead and use a Monte Carlo algorithm to simulate how many tasks this team can deliver in 30 days, we’ll obtain the following histogram.

In this histogram, you can see a significant number of possible outcomes for this team: they may deliver anywhere from 0 to 90 tasks. Furthermore, there are plenty of likely scenarios in this distribution.

Now, let’s change the throughput samples we used in our simulation. This time, we’ll consider the team working on one task at a time, delivering in more regular intervals, instead of working on plenty of tasks in parallel and delivering them all on the same day.

// Each item represents the number of tasks delivered that day

const TEN_DAY_THROUGHPUT = [1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 0, 1, 1, 1];

Please notice that the team still delivered the same amount of tasks in those ten days. The only difference between these teams is that the second delivered tasks more uniformly.

Simulating such a team’s performance yields the histogram below.

If you compare these two histograms, you’ll see that the second histogram’s distribution has fewer possible outcomes — 20 to 41 tasks instead of 0 to 90 —and results are more clustered towards the centre. In other words, its standard deviation is smaller.

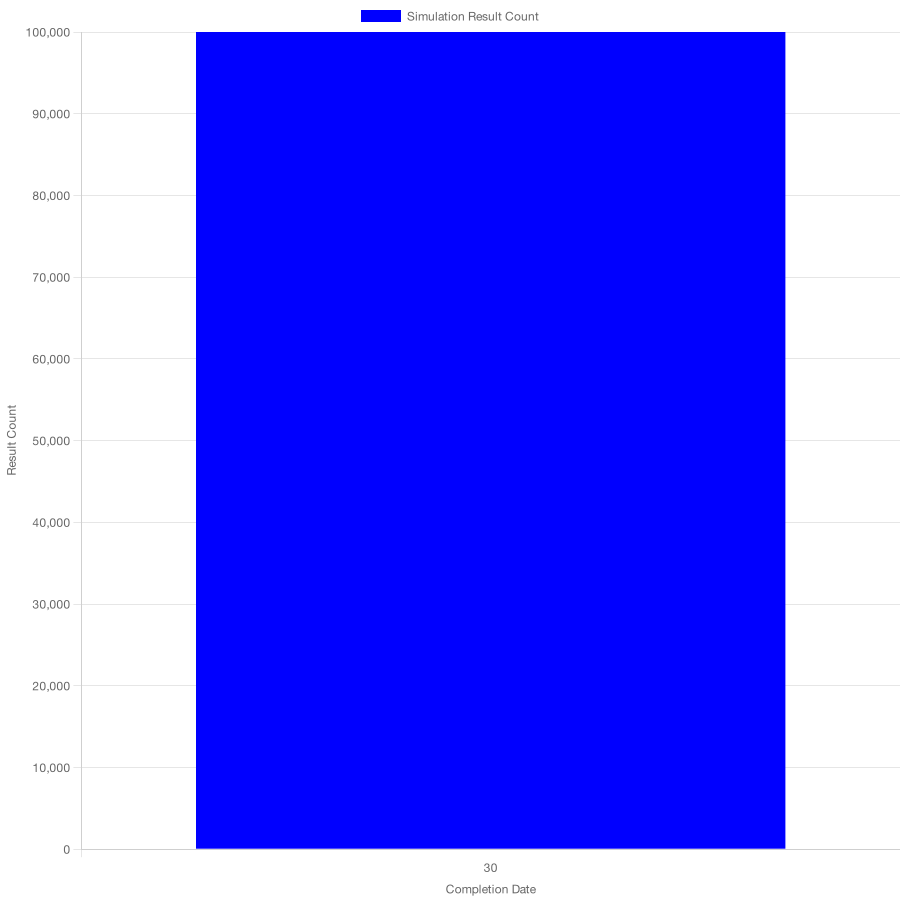

To make my point even more obvious, let’s see what happens if we assume the team always delivers one task each day.

// Each item represents the number of tasks delivered that day

const TEN_DAY_THROUGHPUT = [1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1];

Assuming our team will remain hyper-consistent, there’s only one possible outcome in the next 30 days: they’ll deliver 30 tasks.

The comparison between those three histograms leads to the conclusion that teams which deliver tasks more uniformly are more predictable, even if they deliver the same number of tasks within the period we’re using as the sample for our simulations.

Putting it all together

When you start a new task before finishing the previous, average cycle times will increase. That happens because you’ll increase the number of items in progress but maintain the same throughput.

Little Law illustrates this behaviour by establishing a clear relationship between cycle time, work in progress, and throughput.

Additionally, there’s a cost to context-switching when it comes to software development tasks.

Teams which start tasks earlier than they should must also write specifications earlier. Therefore, they’ll waste an opportunity to gather feedback, digest it, and incorporate it into a feature’s specification, diminishing its chance of success.

Many times, teams will have multiple tasks in progress because moving a task from one stage to the next is costly. Consequently, these teams will attempt to transfer tasks from one stage to another in large batches to pay this high transaction cost only once.

The problem with large batch transferrals in the software industry is that the cost of holding these tasks increases exponentially because their specifications perish, and change deltas increase, making it more difficult to find bugs. This increase in deltas also complicates change management, harming the system’s reliability.

One last benefit of working on smaller batches of tasks at a time is that it makes teams more predictable. Delivering the same number of tasks uniformly is better than delivering multiple tasks at once because it makes cycle times uniform too. In turn, those uniform cycle times help you make better forecasts, as there will be fewer possible outcomes when simulating (or estimating) the team’s performance.

Further reading

I have questions, but I need a burger First

If you have questions or comments, send me a tweet at @thewizardlucas or an email at lucas@lucasfcosta.com.

If you’re in London and need a burger, go for Honest Burgers’ “Tribute” (and don’t forget the rosemary salted chips).

In São Paulo, Brazil, order Tradi’s “oráculo”.

These are all personal recommendations. Probably none of these burger shops know this post even exists.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2IBMUmu

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.