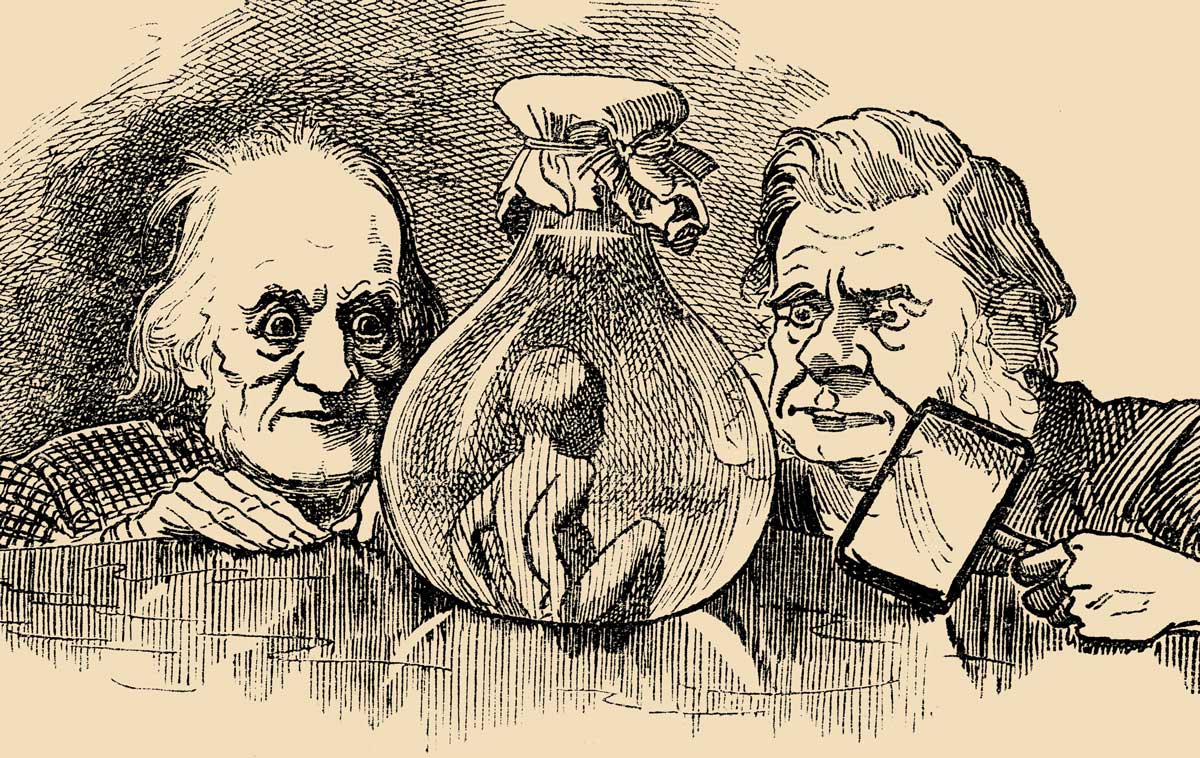

Born into an illustrious scientific family, the future biologist Julian Huxley was a precocious child. At the age of five he came across a caricature by the eminent illustrator Linley Sambourne in the enormously successful children’s fairytale, The Water-Babies, written by Charles Kingsley. First published in 1863 with only two plates, it had sold so well that Sambourne was commissioned to produce a lavish new edition. The central character is an ill-treated chimney sweep called Tom, who falls into a river and is transformed into a water baby. During a long series of encounters with other children and teachers living beneath the surface, he eventually learns to follow the codes of Christian morality – the book’s major theme. In the illustration Julian recognised his square-jawed grandfather, Thomas Henry Huxley, brandishing a magnifying glass as he peers at a small naked boy imprisoned in a flask of liquid. Next to him is a balding scientist in a check jacket – Huxley’s arch rival, Richard Owen, an obstinate man renowned for nurturing enmities. A museum-based expert on fossils, Owen coined the word dinosaur, yet adamantly refused to accept that human beings had evolved from apes.

‘Dear Grandpater’, Julian wrote, ‘Have you seen a Waterbaby? Did you put it in a bottle? Did it wonder if it could get out? Could I see it some day?’ The elderly scientist replied diplomatically but enigmatically to these questions: posed innocently, they nevertheless went right to the core of the scientific quandaries addressed by Kingsley in his book.

Science and religion

As in previous centuries, there was no straightforward, black-and-white opposition between religion and science. Kingsley was a cleric and a naturalist who endorsed evolution by natural selection, while Owen was an eminent scientist who opposed Darwinism yet believed that God superintended the development of the living world. Some of his most famous discoveries were of extinct creatures, even though, according to his strict interpretations of the Bible, God initially created the living world just as it is now.

Sambourne and Kingsley both knew Huxley, Charles Darwin’s self-appointed publicity agent who is now best known for confronting Bishop ‘Soapy Sam’ Wilberforce during a fierce debate at Oxford about Darwinian evolution. Wilberforce had reportedly asked sarcastically whether Huxley had descended from an ape on his grandmother’s or grandfather’s side. Still only an undergraduate, his victim promptly retorted that he would rather be related to an ape than to an intellectually dishonest man.

In his long allegorical narrative, Kingsley imagined his own small son voicing similar concerns to Julian Huxley’s. The fictionalised boy argued that, if Tom – the water baby of Kingsley’s title – really had been found, surely someone would have ‘put it into spirits [or] cut it into two halves, poor dear little thing, and sent one to Professor Owen, and one to Professor Huxley, to see what they would each say about it’. Kingsley reassured his young readers that Huxley was ‘a very kind old gentleman’, who would have kept Tom alive and petted him. Nevertheless, in The Water-Babies he fondly parodied Huxley as the foolish Professor Ptthmllnsprts – Put-them-all-in-spirits – who believed that anatomical analysis would yield the secrets of life.

Kingsley and Huxley admired each other’s intellect but were fundamentally opposed on the subject of religion. Whereas Kingsley was a devout Anglican clergyman, Huxley invented the term agnosticism to cover his own position, maintaining that, without definitive evidence, he lacked the certainty to be either an atheist or a Christian. After Huxley’s son died of scarlet fever Kingsley was his friend’s main source of comfort. He never convinced the grieving man to put his faith in God.

In The Water-Babies, Kingsley derides the value of Huxley’s logical rationality for solving the world’s mysteries. At one level a fairy story, the book is laced with multiple themes, although Kingsley stated his central message clearly: ‘Your soul makes your body, just as a snail makes its shell.’ Much as he appreciated the value of objective scientific research, Kingsley attached great significance to nature’s wonder, creating his book to refute the materialist view that life can exist independently of a spiritual God.

A celebrated cleric

When he wrote The Water-Babies, Kingsley was Regius Professor of History at Cambridge, but – as is apparent from his evocative accounts of the creatures and landscapes Tom encounters – he was also a keen geologist and zoologist. Uniquely among theologians, Kingsley immediately supported the theory of evolution by natural selection when it was proposed by Darwin in On the Origin of Species in 1859. Gratified but surprised, Darwin opportunistically incorporated his approving comments in all future editions of the book, anonymising Kingsley as a ‘celebrated cleric’. According to Kingsley’s singular interpretation, Darwin’s theory relied on the noble concept of a deity who had ‘created primal forms capable of self development’. This far-seeing God had made living beings that could improve themselves, so there was no need for repeated divine interventions to fill in the gaps between different types of living creature.

Victorian families often read books aloud to one another and Kingsley evidently assumed that helpful adults would be on hand to clarify the obscurer points of his topical jokes. In an aside to his young readers he points out that, as a logical rationalist, Professor Ptthmllnsprts should recognise the inherent impossibility of proving a universal negative. How can you be sure that some strange creature does not exist just because you have never seen it? As the learned professor wanders along a rocky shore with Tom’s subaquatic friend Ellie, she asks the professor how he can possibly know that there is no such thing as a water baby. Forced into a logical cul-de-sac, Ptthmllnsprts resorts to a most unsatisfactory reply: ‘Because there ain’t.’ Turning away, he begins angrily poking among the weeds, but is horrified to see that Tom has become tangled up in his net. Instead of welcoming the living proof he has demanded, he retreats into outright denial and throws the water baby back into the water, ignoring the children’s protests.

Of moas and men

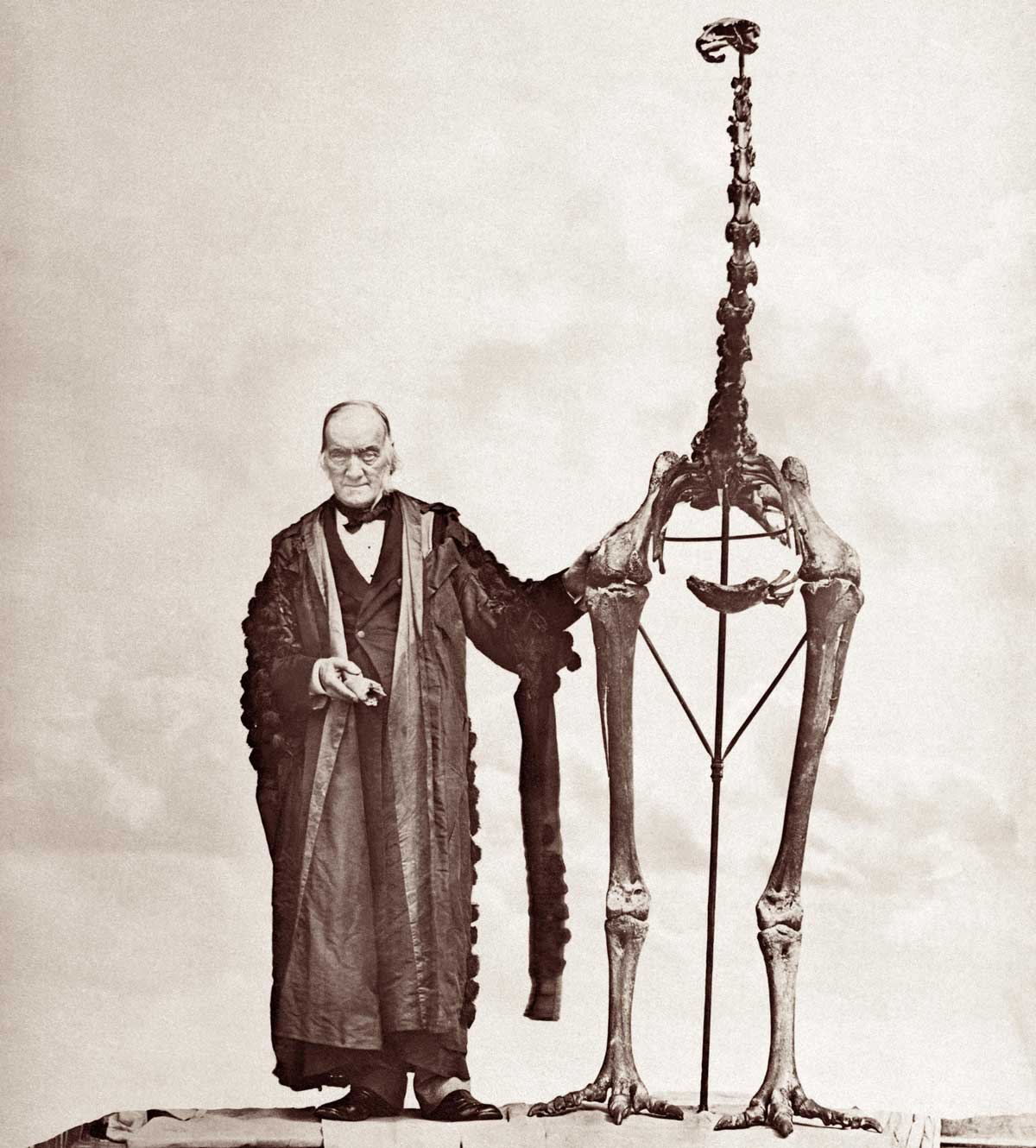

Although he refused to accept that people had evolved from apes, Owen was a renowned fossil expert, celebrated for his ability to reconstruct an entire extinct creature from a small fragment. In 1839, as a young unknown anatomist, he concluded that the broken shaft of a thigh bone sent to him from New Zealand had originally belonged to a sluggish struthious bird (the technical term for ‘ostrich-like’). Despite scathing criticisms Owen persevered, distributing 100 copies of his article to rouse interest among naturalists. Within a few years, he had been sent so many bones that he was able to identify more than a dozen species of vanished moa birds. In a striking photograph a massive skeleton dwarfs, yet strangely mirrors, its human discoverer with his concave face, large eyes and thin, stooped body.

Owen was the first to provide definitive evidence that these giant birds had once existed in New Zealand and he became fondly known as ‘Old Bones’. According to Maori tradition, moas had brightly coloured necks, sported a crest on their heads and devoured unsuspecting forest travellers. Even though there was no confirmed report of a European sighting, before the islands had been thoroughly explored it was tempting to imagine that a few might survive in remote regions. It seemed that these giant birds had only very recently become extinct. Owen later bought for the British Museum a specimen from New Zealand bearing skin, ligaments and grayish-brown feathers. Some moa bones bear marks that might have been made with iron blades; he blamed human beings for hunting the birds so heavily that they could not survive. European travellers may well have been the last people to dine on moa.

By coining the word dinosaur, Owen helped to bolster an evolutionary theory in which he did not believe. Infuriatingly for him, it was his arch-rival Gideon Mantell who had been the first to unearth a few mysterious teeth in a quarry in 1822, which he claimed belonged to exceptionally large relatives of iguanas (subsequently called iguanadons to incorporate the Greek word for ‘tooth’). Two years later William Buckland – a clergyman and palaeontologist based in Oxford – made a still more momentous discovery of some gigantic fossil bones and so became the first person to describe what is now known as a dinosaur. But it was Owen who later supplied the label. Interpreted charitably, Owen was trying to make sense of all the fossil reptiles that had so far been dug up by bracketing them within a single group of dinosaurs. Viewed more cynically, he was an ambitious young career scientist keen to attack Mantell, an older doctor who worked on fossils in his spare time.

Champion chomper

Buckland never did get the opportunity to sample moa flesh, but he was an extremely adventurous Victorian gourmet who chomped his way through an extraordinary variety of animals. Although after one of these gastronomic experiments he refused to eat mole again, he regularly served his guests with delicacies such as panther steaks and mice on toast. Then, after the meal, he would reveal that the strange oval objects set inside the glass tabletop were sliced coprolites (fossilised dinosaur faeces).

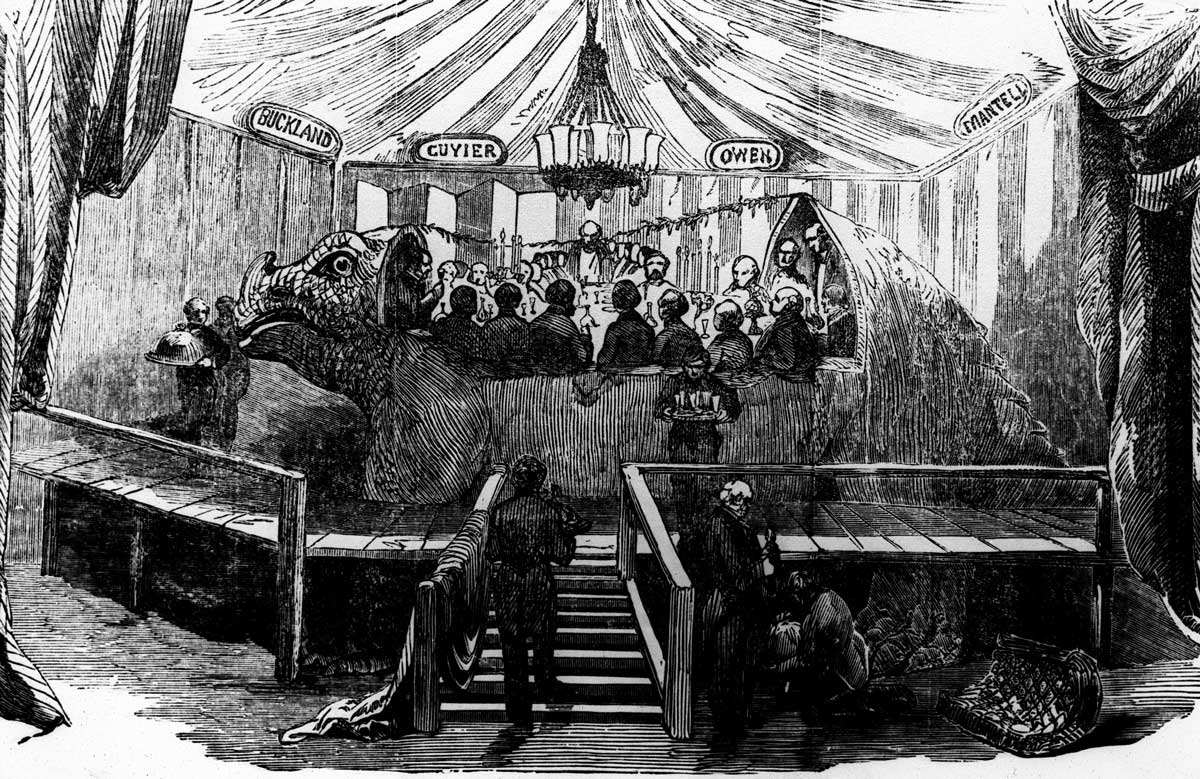

A more orthodox menu was supplied for a bizarre seven-course dinner party held as a publicity stunt to celebrate the New Year of 1854. This banquet took place at Crystal Palace inside the mould that was being prepared to produce a model iguanodon. Owen took his place at the head of a table with some 20 guests surrounded by pink and white drapery. When completed, the iguanodon contained 600 bricks and 100 feet of iron hooping, as well as tiles, stone and 38 casks of cement, although Owen – who had been excluded from the decision-making – repeatedly and tactlessly stressed that there was no evidence for the prominent horn on its snout. During the next half a century over a million visitors a year came to admire this massive beast and its 32 antediluvian companions, a supposedly realistic group assembled in Crystal Palace Park on the outskirts of London, where they can still be admired today.

Hippopotamus on the brain

Over many years Huxley and Owen confronted each other in savage debates that were fuelled by personal animosity, but which also represented contrasting approaches to the processes of evolution. Symbolically, their protracted row hinged on one tiny anatomical feature – a fold in the layers at the base of the brain called the hippocampus minor. With his reputation for inferring big conclusions from minute scraps of bony evidence, Owen insisted that this feature was found only in human brains. For him, the hippocampus minor provided clinching evidence against human beings having primate ancestors. But many other scientists were reluctant to dismiss evolution by natural selection on such an apparently flimsy basis. Huxley repeatedly accused him of ‘lying & shuffling’ and of dishonestly ignoring a host of other observed features.

In The Water-Babies, Kingsley parodied Owen’s position succinctly but ruthlessly. Your appearance and your behaviour are irrelevant, he sarcastically informed his Victorian audience; ‘the one true, certain, final and all-important difference between you and an ape is, that you have a hippopotamus major in your brain, and it has none’. But he also mocked Huxley’s avatar, Professor Ptthmllnsprts, for adopting a similarly narrow-minded approach and seeking to prove Owen wrong by focusing on anatomic features of non-human primates. Other differences are more important, Kingsley argued, ‘such as being able to speak, and make machines, and know right from wrong, and say your prayers …’.

Charles Darwin must have felt both disconcerted and delighted to find this theological naturalist in his camp. The subtleties of The Water-Babies may have been beyond the grasp of many children, but – as Julian Huxley exemplifies – the book and its illustrations provided a wonderfully effective piece of propaganda for the subversive doctrines of Darwinism.

Patricia Fara is an Emeritus Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge. Her latest book is Life after Gravity: The London Career of Isaac Newton (Oxford University Press, 2021).

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/FMHupJr

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.