My experience with a pioneering JavaScript framework

Note: I am not currently affiliated, nor have I ever been at any time, with Meteor Development Group, Apollo, or Tiny. These are my own personal thoughts.

If you only got into web development in the past couple years, you might quite possibly have never heard about Meteor.

But when it first came out in 2012 (before React or Vue even existed!) it was the hottest thing around for a while. Not only that, to this day Meteor still does many incredible things that the rest of the ecosystem has yet to catch up with.

And what’s more, even if you’ve never used Meteor I’m willing to bet you’ve used software that was influenced by it, one way or another. So read on to learn more about Meteor’s early rise, why it may have burned too bright, and the lasting impact it had on modern JavaScript development.

Before we move on: this essay is a reflection of my own personal experiences with Meteor and its community, and is not meant to be an exhaustive or impartial history of the project.

2012

Take yourself back to 2012. It’s the aftermath of the financial crisis, but Barack Obama is president of the U.S. and assuring the world that there’s hope. “Call Me Maybe” is topping the charts. And tech founders are to be admired (or at the most made fun of), not yet feared for their over-sized power.

Deep in Silicon Valley, a team of brilliant engineers currently enrolled in YCombinator has a realization: building web apps is too damn hard!

Out of this realization is born Meteor: a unified architecture on top of Node.js that bundles client, server, and database all in one neat little package that you can run (or even deploy for free!) with a single command.

What’s more, it was all reactive and in real-time! Can you imagine never having to write a fetch() or worrying about updating your client data cache? And all that using the same familiar MongoDB API syntax both on the server and client!

Yep, it turns out Meteor was already tackling a huge chunk of the problems of modern web development in 2012.

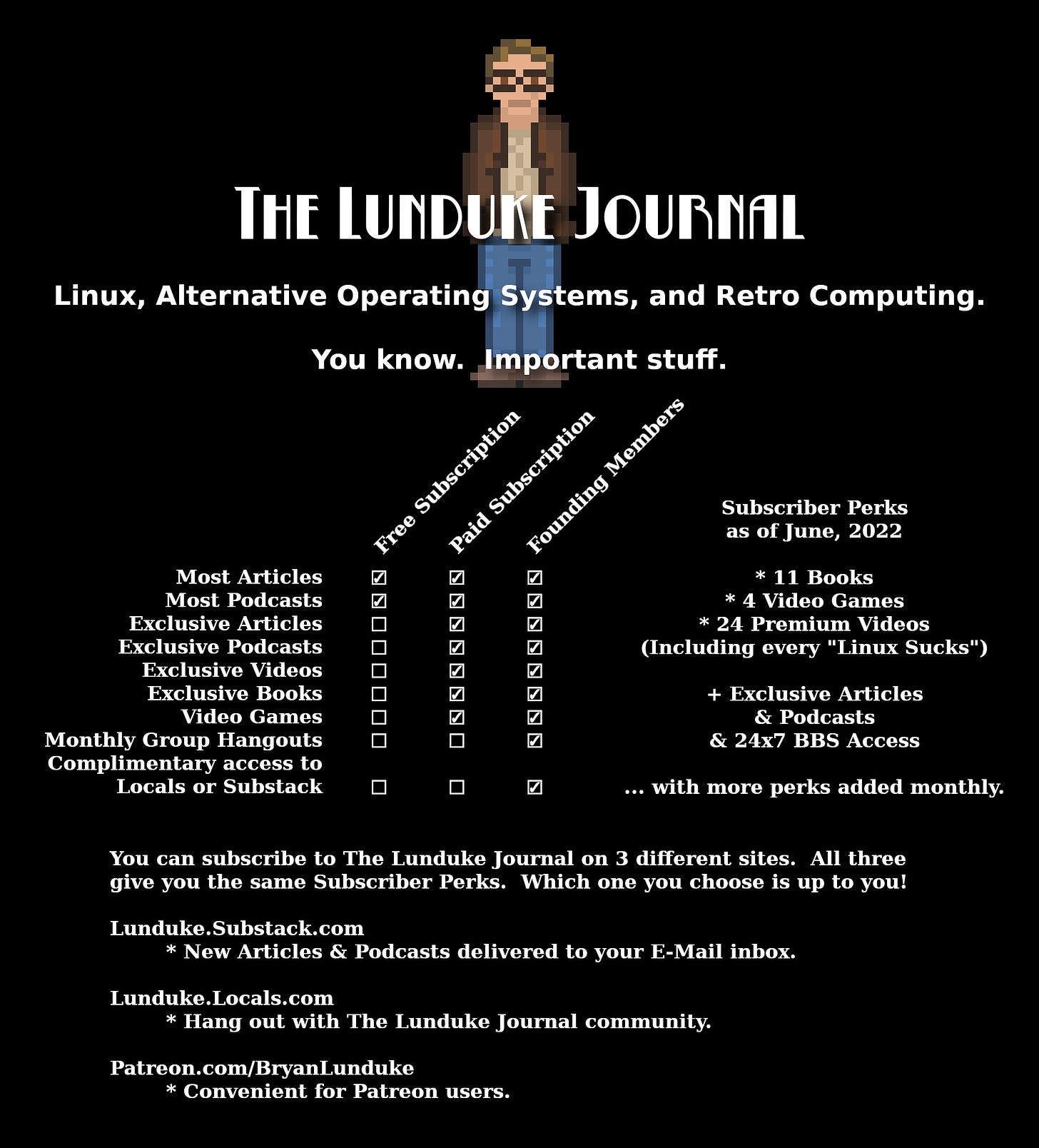

Do you use GraphQL? If you do, and have 15 minutes to spare, please consider taking the first ever State of GraphQL community survey! We just launched it, and we think it’s going to be a huge help to figuring out which GraphQL tools and features people actually enjoy using.

A Lone Pixel-Pusher

Way back in the early ’10s I was earning a living tweaking drop shadows in Photoshop. As strange as it seems today, this was the tool of choice when it came to designing websites. This being the heyday of iPhone-inspired skeuomorphism, your paycheck depended on your ability to simulate a realistic leather texture for that call-to-action button.

Like many other UI designers though, I felt disillusioned that my beautiful creations didn’t always survive the rocky transition from Photoshop to browser in one piece. This, along with a generous dose of Silicon Valley kool-aid (I had just been to the Valley for the first time in the summer of 2011, and it made a huge impression on me), pushed me to try and strike it rich on my own rather than keep playing second fiddle to unappreciative developers.

I wasn’t starting from zero either: long before pushing pixels I had obtained my computer science diploma, even if I wasn’t quite top of my class. For example, I was once suspected of plagiarism because I was incapable of explaining what my own code did (my defense: if I was going to copy somebody else’s code, I would’ve copied something that works!). But web development had to be easier than C and Java, right?

I went through Michael Hartl’s Rails Tutorial but got overwhelmed with too many new concepts at once: routes, models, controllers, views, auth… All this combined with having to learn a new language meant Rails never quite clicked for me.

On the other hand, something that did click was jQuery. It was JavaScript, which was a “normal-looking” programming language compared to Ruby, but with all the weird DoSomethingWithTheDOM() parts massaged into a sensible API.

The first project I built with jQuery was a little tool called Patternify, which still exists to this day! I had a ton of fun, but at some point I started being frustrated once more: playing around in the browser was fine, but to achieve anything big you needed to involve a server and a database at some point.

My first client-side only web app: a pixel pattern drawing app.

So here I was, a designer-slash-front-end-developer who loved JavaScript but was deathly afraid of servers. In other words, the perfect audience for Meteor.

Discovering Meteor

Meteor made a big splash right from the get-go, with one of the biggest Hacker News launches of all time. As one commenter put it:

My first impression of this: wow. If Meteor is all it appears to be, this is nothing short of revolutionary.

And revolutionary it was. Once my friend Sean Grove pointed me to it (he was in the same YCombinator batch as the Meteor guys), Meteor immediately appealed to me.

At the time, I was trying to build a “Hacker News for designers”, something that for whatever reason nobody has ever quite succeeded in doing. With its real-time capabilities, Meteor seemed like the perfect for this kind of web app. I got to work, deciding to make the project open-source in the hopes of attracting unpaid labor like-minded contributors, and Telescope was born.

The default Telescope theme.

Throughout this whole process I got to know the other members of the budding Meteor community, one of which was Tom Coleman, creator of Meteor’s first package manager (Meteor launched without any kind of first-party package manager and only supported regular npm packages much later, which seems hard to imagine today).

Spotlight

Tom founded development agency Percolate Studio with longtime collaborators Dominic Nguyen and Zoltan Olah. Later, the company was acquired by Meteor Development Group, and after that the trio went on to found Chromatic and maintain Storybook, the popular UI testing tool.

I was fresh off writing a somewhat successful design e-book so I approached Tom with a proposal: we’d combine his deep knowledge of Meteor and my design and marketing skills to write a Meteor tutorial book and establish ourselves as the de facto way to learn the framework just as it was taking off.

And guess what: we did exactly that! Discover Meteor launched in 2013 and thanks in no small part to a big boost from the Meteor team quickly became one of the main resources to learn Meteor, just as we had hoped. The book quickly became a big part of both our lives, and was also a big financial success (you can read this Gumroad case study to learn more).

Discover Meteor is no longer maintained and you can now read it for free.

We even had a podcast and a t-shirt, and I’m not sure how many other programming books can say the same. And did I mention Discover Meteor was also translated into dozens of other languages by volunteers (we made all the translations freely available)?

Fun fact: to this day I’ve still only met Tom in person once, for the Discover Meteor launch!

Things Cool Down

At first, it seemed like everything was great in Meteor land. Tom eventually went to work for the Meteor Development Group (the company behind Meteor, also known as MDG) itself, the Meteor community was growing, and the book was doing great.

Spotlight

Arunoda created libraries to address many under-served aspects of early Meteor days including routing, server-side rendering, deployment, and performance monitoring. He went on to create Storybook, and work for Vercel before creating gamedev company GDi4K.

But as the rest of the JavaScript ecosystem kept evolving (this is around the time React was gaining traction), many voices inside the Meteor community started questioning Meteor’s idiosyncratic approach.

It soon became clear that the community was splitting into two camps: those who appreciated Meteor’s clear value proposition of simplifying web development by providing an all-in-one environment, and those who wanted more openness towards the npm ecosystem to avoid being left behind by the rest of the webdev community.

Here’s the catch: the contents of the book clearly targeted the first camp, but we as programmers were firmly in the second. Were we supposed to keep advocating for practices we didn’t follow ourselves? Or should we rewrite the book from scratch to match what we actually did, in the process risking killing the very simplicity that made the book appealing in the first place?

We could never decide, and Discover Meteor slowly got out of date. And once Tom left the Meteor Development Group and stopped using Meteor altogether, it was clear that our adventure had come to an end.

7 Principles, 10 Years Later

Meteor was famous for its “7 Principles”, which made up the core of its philosophy. Let’s look back to see how they hold up 10 years later when applied to the JavaScript apps of today.

1. Data on the Wire. Don’t send HTML over the network. Send data and let the client decide how to render it.

Verdict: 👎

It’s since become apparent that you often do need to send HTML over the network, and things seem to be moving back towards handling as much as possible of your HTML compilation on the server, not on the client.

2. One Language. Write both the client and the server parts of your interface in JavaScript.

Verdict: 👍

It’s now become commonplace to reuse components on both the server and client but that wasn’t the case 10 years ago. And to this day Meteor still handles many aspects of server/client code sharing better than most other frameworks.

3. Database Everywhere. Use the same transparent API to access your database from the client or the server.

Verdict: 👎

The ability to write MongoDB commands (with some security constraints) from your browser was a big innovation at the time, but that paradigm never got popular beyond the borders of the Meteor community.

4. Latency Compensation. On the client, use prefetching and model simulation to make it look like you have a zero-latency connection to the database.

Verdict: 🤷

Also referred to as Optimistic UI, Latency Compensation is the idea of immediately showing the user the result of their actions by simulating the server response. While a nice idea in theory, in practice the complexity of updating the client cache and handling error states often makes it more trouble than it’s worth.

5. Full Stack Reactivity. Make realtime the default. All layers, from database to template, should make an event-driven interface available.

Verdict: 🤷

While many frameworks embraced client-side reactivity (starting with, well, React), Meteor’s full-stack reactivity has never been replicated quite the same way. While invaluable for chat apps, games, and other real-time apps, it can often become a performance-hungry liability for more “traditional” web apps.

6. Embrace the Ecosystem. Meteor is open source and integrates, rather than replaces, existing open source tools and frameworks.

Verdict: 👍

If anything, Meteor didn’t go far enough in this direction, since it still had its own build tool, package manager, etc. Today using the ecosystem is just a no-brainer for any new project.

7. Simplicity Equals Productivity. The best way to make something seem simple is to have it actually be simple. Accomplish this through clean, classically beautiful APIs.

Verdict: 👍

Meteor was, and still is, a pioneer in terms of simplicity and ease of use.

Burning Out

Tom wasn’t the only one who wanted to explore new skies. MDG itself had ventured into the GraphQL space, and soon pivoted to become Apollo, the company responsible for Apollo Client and Apollo Server among many other key building blocks of the GraphQL ecosystem.

Out of Meteor, Apollo was born.

So what went wrong? I’m not privy to any inside information so this is just speculation on my part, but I think the team realized that the amount of work required to make Meteor work on a large enough scale to repay their investors was just too much. As it existed, Meteor could work as a niche tool for a specific kind of project, but it could never establish itself as a dominant force in enterprise software, which is where all the real money is.

Achieving this would not only have required years of additional effort, but also throwing away most of the past five years of work, alienating their current community in the process. So just like there was never a newer, better Discover Meteor 2.0, MDG also never launched a Meteor 2.0 to address its current flaws and instead wisely chose to focus on Apollo and move on.

From Telescope to Vulcan

While others had moved on, I on the other hand wasn’t out of Meteor land by any means.

Right from the start, my goal had been to find a framework that would let me launch web apps quickly and easily with JavaScript (the famed “Rails for JavaScript”, if you will), and although Meteor came close, it wasn’t quite there yet. Things like forms, models, internationalization, permissions, etc. were all missing, and I’d had to handle them myself for Telescope.

But what’s interesting is that although I had intended for Telescope to be a Hacker News clone, people had started using it for all kinds of different community-based apps, tweaking the templates to match their use case. This was such a cool direction that I decided to pivot the project to become a full-fledged general purpose web framework, and thus Vulcan.js was born.

Vulcan.js: a valiant attempt at creating the fabled “Rails for JavaScript”.

Looking back, building Vulcan on top of Meteor instead of starting from scratch was not a good idea to say the least. I was hamstrung by all the same issues that Meteor was plagued with, without any of Meteor’s advantages since I had eschewed the traditional Meteor building blocks in favor of React & co.

I had made the bet that the current Meteor community would see Vulcan as its escape raft towards the larger JavaScript ecosystem, a way to port their pure-Meteor apps to a hybrid Meteor-and-React model. But by then, the people who wanted to abandon Meteor had already long done so, and the remaining community of die-hards used Meteor because they actually liked it.

Then again, there was no way I could’ve built something like Vulcan from scratch without standing on Meteor’s shoulders, so maybe it had to be this way? And despite its relative obscurity, Vulcan has been used by others to build startups, was used at a time by popular community LessWrong, and has been used by myself to build multiple sites, including Sidebar (a design newsletter with over 80,000 subscribers) and an AirBnB-like apartment rental platform.

Today, thanks to the efforts of Eric Burel, the new version of Vulcan runs on Next.js. We’re trying to take the philosophy of Meteor, along with everything we learned in the past 10 years, and port it to the modern JavaScript ecosystem, similar to something like RedwoodJS. The amount of work involved is daunting, and makes me all the more admirative of the original Meteor team, who didn’t have React, Next.js, or GraphQL to leverage.

Meteor Today

In 2019, MDG sold Meteor to Tiny, a Canadian company that also owns Dribbble, Creative Market, and many other companies you probably know.

This marked a turning point for the framework: rather than try to conquer the world, Meteor would now focus on pleasing its existing community and growing at its own pace. This leaves us with a paradox: technically speaking, Meteor is the best and most stable it’s ever been; yet there is little interest in learning it from people who aren’t already using it.

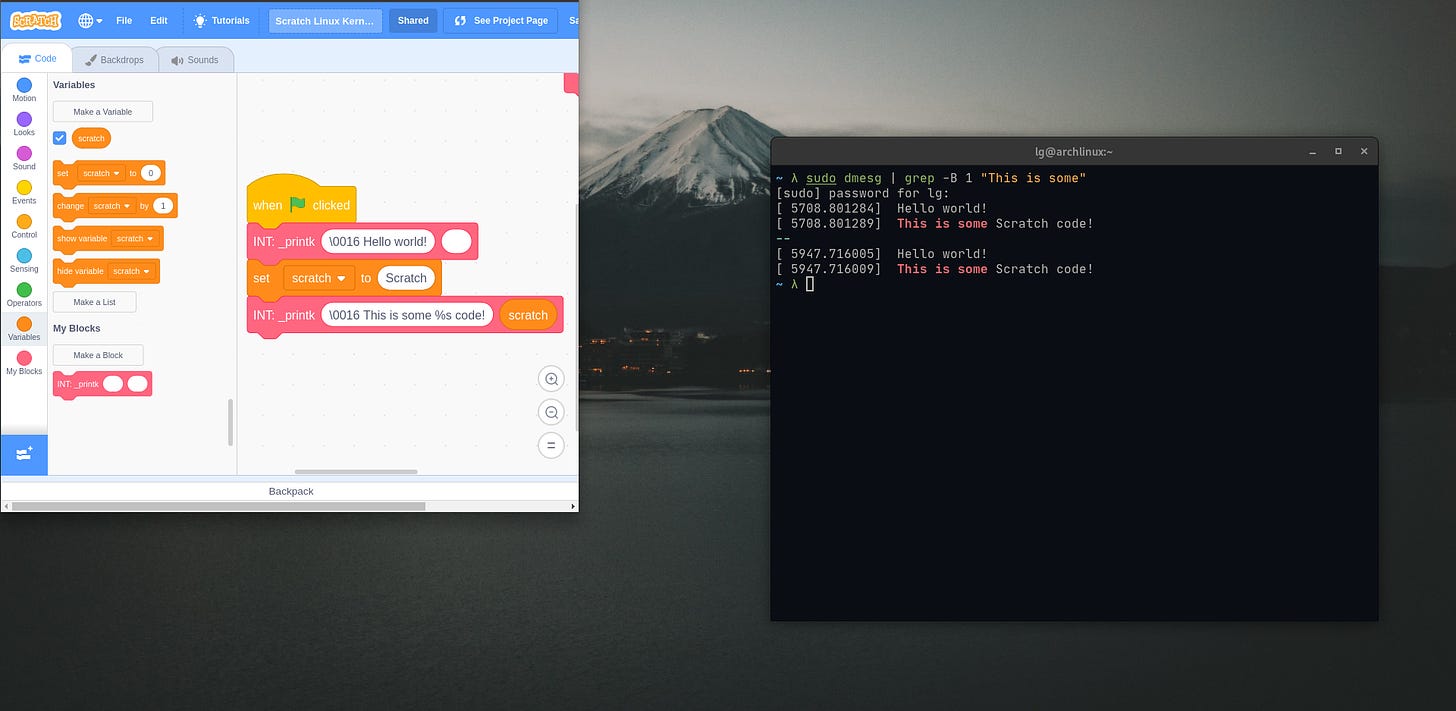

According to the State of JavaScript survey, the percentage of developers interested in learning Meteor (lighter teal bars) has been steadily going down.

And maybe that’s fine. After all, as the creator of a very-niche-but-beloved framework myself, I’m in no position to be casting any stones.

Still… I can’t help but think about what could have been. What if Meteor had taken over the world like we all hoped it would? What if the problems that still plague web development to this day (state management, reactivity, data fetching) had been dealt with once and for all a decade ago?

Meteor today: much improved, but still very niche.

The Meteor Legacy

At this point you might be forgiven for thinking that Meteor burned too bright and fizzled out in the night sky without leaving a trace. But you’d be mistaken. Meteor did make a lasting impact, in more ways than one.

Spotlight

Probably the most famous Meteor alumni, Evan You worked on Meteor’s own Blaze UI framework before going on to revolutionize the front-end space with Vue.js.

One of the new front-end frameworks that quickly outgrew Meteor’s own popularity was Vue, created by Evan You. And where did Evan work before creating Vue? You guessed it, MDG.

Or, you might’ve heard of a tool named Storybook. It was created by Arunoda Susiripala, who was by far the most active open-source Meteor contributor (in fact a running joke was to talk about “the Arunodas”, plural, because his output was too much to be the work of a single individual).

Today, Storybook is maintained by a company called Chromatic, which was co-founded by a certain Tom Coleman. Remember him?

And like I mentioned previously, the original Meteor team itself went on to create Apollo.

And well, I guess there’s also me. Back in 2016 I launched the annual State of JavaScript developer survey. It’s no Vue or Storybook, but it did establish itself over the years as one of the largest independent developer surveys around, and went on to spawn first the State of CSS and now the State of GraphQL surveys. And the whole reason why I launched this survey in the first place was because I was so confused by the JavaScript ecosystem at large, after being coddled by Meteor’s walled garden for so long!

A New Direction for Web Apps?

As I reflect on Meteor, an old debate has come back from the grave to once more rock the web development web: SPAs vs MPAs.

Single-Page Applications are apps that load all their JavaScript with one request, and then function more or less as a self-contained little piece of software from then on. On the other hand, Multi-Page Applications make back-and-forth requests to the server every time you navigate to a new page, thus their name. SPAs tend to have much of their logic run on the client (and also on the server for that first load, if server-side rendering (SSR) is supported), while MPAs have much lighter clients that are less resource-hungry.

Spotlight

Jan is one of the many people that keep the Meteor community alive today thanks to initiatives like the Meteor Impact online conference.

While I’ve always been bothered by the downsides of SPAs, I always thought the gap would be bridged sooner or later, and that performance concerns would eventually vanish thanks to things like code splitting, tree shaking, or SSR. But ten years later, many of these issues remain. Many SPA bundles are still bloated with too many dependencies, hydration is still slow, and content is still duplicated in memory on the client even if it already lives in the DOM.

Yet something might be changing: for whatever reason, it feels like people are finally starting to take note and ask why things have to be this way. Remix has taken the React community by storm by offering a back-to-basic, performance-first approach, while Next.js is embracing React Server Components to solve some of the same issues.

Even tools that are more on the static side of things are evolving, with a new crop of options like Astro, Capri, or Slinkity letting you control which components to hydrate or not.

To say nothing of up-and-coming front-end frameworks like Marko, Qwik, and Solid, which are all about giving you better control over rendering and being more efficient. While over in Deno land, Fresh also embraces so-called “island architecture”.

Ten Years

A lot has changed in 10 years: between political upheavals, a devastating pandemic, and of course worsening climate change, the naive optimism of the early 2010s seems almost quaint. And we’re also more conscious of the fact that access to fast internet connections and modern devices is not always equally distributed throughout the population.

In this new context, Meteor’s all-real-time-all-the-time approach can seem a bit wasteful and excessive.

Don’t get me wrong, I enjoyed pushing the boundaries of the browser and redefining what a web app could be as much as anybody else. But as we enter JavaScript’s third age, maybe it’s time to slow down and build web apps in a more efficient and sustainable manner. All I can hope for is that we still manage to preserve just a tiny bit of that original Meteor magic and simplicity.

After all it’s been 10 years, but there’s yet to be another web framework that burns quite as bright as Meteor did at its zenith.

Webmentions

I attended the Meteor book release party in May 2013. Those truly were inspiring times to be a front end engineer and I thank you and others for the effort you put in those long years ago. Discover Meteor remains one of the finest pieces of tech writing I have ever seen. 👏

https://twitter.com/BradLedford/status/1541973372719902721

Thanks Sachs, what a great write up! Meteor and Discover Meteor had a huge impact on me. They were the perfect tools and environment to learn about full stack. I loved I could easily deploy code and get feedback from friends!

https://twitter.com/ojschwa/status/1541968590928498689