/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/94/2e/942ec9f5-4b0b-44df-a169-3d62d0e9bb8b/harpers_1863_01-_thomas-nast-santa-claus.jpg)

You could call it the face that launched a thousand Christmas letters. Appearing on January 3, 1863, in the illustrated magazine Harper’s Weekly, two images cemented the nation’s obsession with a jolly old elf. The first drawing shows Santa distributing presents in a Union Army camp. Lest any reader question Santa’s allegiance in the Civil War, he wears a jacket patterned with stars and pants colored in stripes. In his hands, he holds a puppet toy with a rope around its neck, its features like those of Confederate president Jefferson Davis.

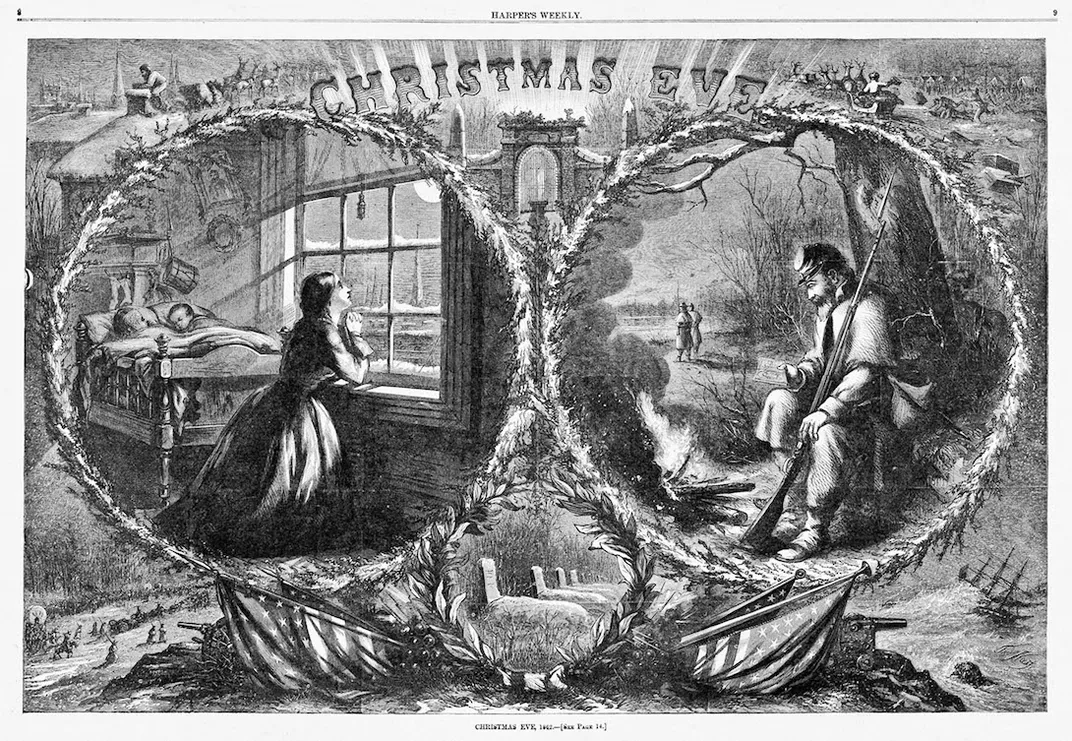

A second illustration features Santa in his sleigh, then going down a chimney, all in the periphery. At the center, divided into separate circles, are a woman praying on her knees and a soldier leaning against a tree. “In these two drawings, Christmas became a Union holiday and Santa a Union local deity,” writes Adam Gopnik in a 1997 issue of the New Yorker. “It gave Christmas to the North—gave to the Union cause an aura of domestic sentiment, and even sentimentality.”

The artist responsible for this coup? A Bavarian immigrant named Thomas Nast, political cartoonist extraordinaire and the person who “did as much as any one man to preserve the Union and bring the war to an end,” according to General Ulysses Grant. But like so many inventors, Nast benefitted from the work of his fellow visionaries in creating the rotund, resplendent figure of Santa Claus. He was a man with the right talents in the right place at the perfect time.

Prior to the early 1800s, Christmas was a religious holiday, plain and simple. Several forces in conjunction transformed it into the commercial fête that we celebrate today. The wealth generated by the Industrial Revolution created a middle class that could afford to buy presents, and factories meant mass-produced goods. Examples of the holiday began to appear in popular literature, from Clement Clarke Moore’s 1823 poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (more commonly known by its first verse, “Twas the night before Christmas”) to Charles Dickens’ book A Christmas Carol, published in 1843. By the mid-1800s, Christmas began to look much more as it does today. “From a season of misrule characterized by drink, of the inversion of social roles in which working men taunted their social superiors, and of a powerful sense of God’s judgment, the holiday had been transformed into a private moment devoted to the heart and home, and particularly to children,” writes Fiona Halloran in Thomas Nast: The Father of Modern Political Cartoons.

This was as true in the United States as it was in England, even with the Civil War raging. Children received homemade gifts due to the scarcity of materials, Union and Confederate soldiers swapped coffee and newspapers on the frontlines, and some did their best to decorate the camp. “In order to make it look as much like Christmas as possible, a small tree was stuck up in front of our tent, decked with hard tack and pork, in lieu of cakes and oranges, etc,” wrote New Jersey Union soldier Alfred Bellard.

It was into this world that the talented artist Thomas Nast arrived in the 1850s. Doing his first sketches as a teenager, he became a staff illustrator for Harper’s Weekly, one of the most popular magazines of the day, in 1862. As Halloran notes, Harper’s Weekly wasn’t just for serious subjects: “It provided political news and commentary on national and international events, but it also offered readers sentimental fiction, humor and cultural news.” What better place for Nast to bring his meticulously detailed image of Santa to life? And so, beginning with the January 1863 drawings, Nast began to immortalize the mythic figure of Santa Claus.

In addition to repurposing the imagery of the Moore poem—reindeer pulling a sleigh, sack full of presents—Nast also found inspiration in his surroundings. He based Santa’s bearded visage and round belly partially on himself and used his wife and children for other characters, says Ryan Hyman, a curator at the Macculloch Hall Historical Museum. Located in Nast’s hometown of Morristown, New Jersey, the museum holds a large collection of his work. “The outside pictures that show rooftops and church spires were all here in Morristown,” Hyman adds.

Though they varied from year to year, Nast’s Santa drawings appeared in Harper’s Weekly until 1886, amounting to 33 illustrations in total. Unsurprisingly, the drawings from the Civil War often fell solidly in the realm of propaganda; Nast staunchly supported abolition, civil rights and the Republicans. But even after the war ended, Nast continued to use Santa Claus to make certain pointed political statements.

Take the 1881 image known as “Merry Old Santa Claus,” probably Nast’s most famous portrait of the Christmas deity. To the casual observer, it looks like Santa, with his bag of toys, wearing his characteristic red suit. But actually, Hyman says, it’s more propaganda, this time related to the government’s indecisiveness over paying higher wages to members of the military. “On his back isn’t a sack full of toys—it’s actually an army backpack from enlisted men.” He’s holding a dress sword and belt buckle to represent the Army, whereas the toy horse is a callback to the Trojan horse, symbolizing the treachery of the government. A pocket watch showing a time of ten ’til midnight indicates the United States Senate has little time left to give fair wages to the men of the Army and Navy.

“Nast was always pro-military,” Hyman says. “The military was up for getting a raise and he knew how hard they worked and how they helped shape the country.”

Even though people may know that Nast gave us the donkey for the Democrats and the elephant for Republicans, and that he took on corrupt New York City politicians, few may realize the role he played in creating Christmas. Hyman and his colleagues hope they can change that, in part through their annual Christmas showcase of Nast’s work. “He created the modern image of Santa Claus,” Hyman says—though we don’t tend to think about Civil War propaganda when we’re opening presents today.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2QLiiZi

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.