Edith Wharton travelled to Morocco in autumn 1917 as a guest of France’s Resident-General Hubert Lyautey. ‘Oh the relief’, she wrote from her hotel in Rabat, ‘of a real holiday.’ For three years, Wharton had immersed herself in wartime work in Paris, where she had set up shelters for Belgian refugees and found work for unemployed seamstresses. She travelled regularly to the Western Front to report on the war for Scribner’s Magazine. Her Moroccan sojourn undoubtedly offered a welcome respite from the discomforts and anxieties of war-torn Europe.

But Wharton’s trip to Morocco was a working holiday. The articles and books that she published about it aimed to convince her American compatriots of the pressing need for a French empire in the Arab world. This year the literary world commemorates the centennial of perhaps Wharton’s most celebrated novel, The Age of Innocence, but 2020 also marks 100 years since the publication of one of Wharton’s lesser-known works, her 1920 travelogue In Morocco.

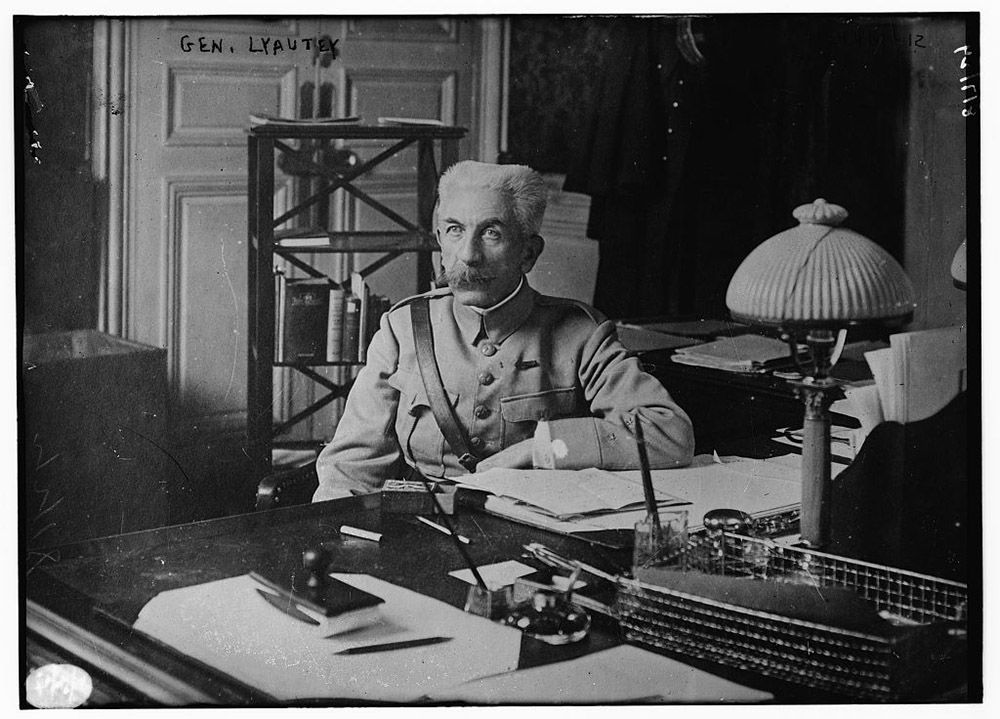

France had appointed Hubert Lyautey as its first Resident-General in Morocco in 1912 after its conquest of the country. Wharton may well have crossed paths with him when he returned to France in early 1917 as Minister of War. Wharton glorified Lyautey. When she stopped in Crévic, Lyautey’s birthplace, she described to her readers how German troops bombed his family home during the Battle of Lorraine. It was an act of revenge, Wharton explained, deeming Lyautey, ‘one of France’s best soldiers, and Germany’s worst enemy in Africa’.

Lyautey understood France’s need for US support. The US had yet to recognise French control over its North African territory when he became Minister of War. Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of State, Robert Lansing, had expressed concern to the French ambassador, Jean Jules Jusserand, that the French Protectorate would negatively affect US commerce. Jusserand refused to provide the US with what were essentially extraterritorial rights in Morocco. This diplomatic foot-dragging sidetracked US entry into the First World War. It was only in January 1917 that Lansing agreed in principle to recognise France’s new Protectorate.

Lyautey’s stint as Minister of War was a short one and he returned to Morocco by April. That year’s Foire de Rabat brought a number of influential public figures to Morocco. Wharton joined a select group of official visitors, political and literary figures who could promote colonial Morocco. She and other guests attended an exhibition where local artisans plied their wares and, in turn, French companies sold modern equipment, from tractors to phonographs. ‘The sight of these rapidly improvised exhibitions’, wrote Wharton, describing Moroccan reactions to the colonial Foire, ‘fascinated their imagination and strengthened their confidence in the country that could find time for such an effort in the midst of a great war’.

Wharton embraced Lyautey’s confident narrative of the benefits of French colonialism. She had long opposed President Wilson, who would soon call for ‘a free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims’. Wharton made no bones about being, in her own words, ‘a rabid imperialist’.

Wharton had an expansive network of influential friends. Jusserand, the diplomat who eventually wrangled US recognition of the Protectorate from President Wilson’s administration, was among them. He had been one of a select list of guests invited to her apartment in Paris when her cousin, Theodore Roosevelt, visited in April 1910. By 1917, the Republican Party seemed poised to nominate Roosevelt as candidate for the presidential election of 1920 (though his death in 1919 precluded his running). As Roosevelt’s cousin and friend, Wharton could garner the attention not just of US readers but also key policymakers.

Wharton arrived in Tangier on 15 September 1917. Situated eight miles from Spain, Tangier was a bustling port city, with milling factories, department stores and a diverse population. Wharton dismissed it as ‘cosmopolitan, frowsy, familiar’. Instead, she sought what her biographer Hermione Lee calls ‘un-Europeanness’.

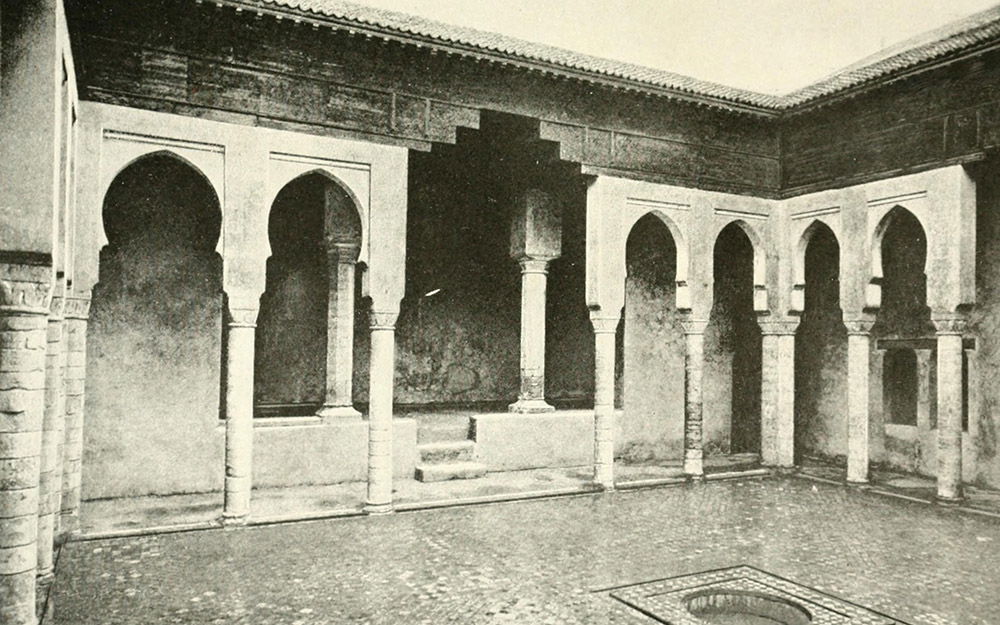

Recognising Wharton’s desire to experience the exotic, French administrators choreographed her trip with care. From Tangier, her handlers drove north to Rabat, where she stayed at the new Hotel La Tour Hassan. Its Moorish keyhole arches, mosaic tiles and sculpted wood evoked the Alhambra in Granada. In Fez and Marrakesh Wharton would stay in the palatial courtyard houses that the French co-opted as local residences, where Lyautey lived and worked.

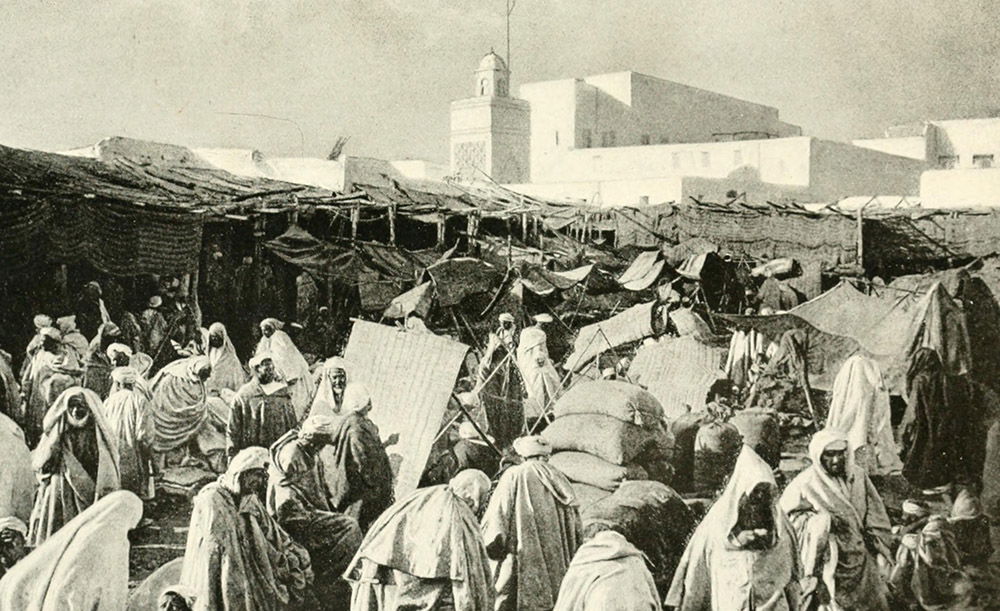

Colonial officers accompanied Wharton to the most ‘un-European’ sites. Her travelogue includes accounts of the ‘barbaric splendor’ of the souks in Marrakesh. She witnessed atavistic religious rites at a mausoleum in Moulay Idriss. She ambled among Roman ruins in Volubulis and visited an old pirate lair in Salé. ‘Even in the new, thriving French Morocco’, she wrote, ‘the outline of a ruin or a look in a pair of eyes shifts the scene, rends the thin veil of European Illusion, and confronts one with the old grey Moslem reality.’

France’s Director of Fine Arts and Historic Monuments, Maurice Tranchant du Lunel, accompanied Wharton for much of her trip. As they walked through the complex street network in the walled medina of Fez, he ranted about the bad taste of Moroccan builders during the era just before colonialism, when Moroccans imported marble and the neoclassical style. Tranchant du Lunel did not perceive urban facelifts in Fez as improvements. Instead, he complained, ‘their architects borrowed European styles that were often boorish’. Clearly, he swayed Wharton, who dismissed ‘the indignity of European improvements’.

Wharton did not wish to see evidence of modernity in Morocco. Her travelogue does not mention her stay in Casablanca, which impressed her travelling companion Walter Berry. President of the American Chamber of Commerce in Paris, Berry described Casablanca as ‘“a boom city” of the Far-West, with its warehouses and factories, its department stores, and its housing developments’. This dynamic city, he concluded, ‘seems to grow while you wait … palpitating with life, a metropolis of a hundred thousand souls, with commerce running into the hundred millions’. Wharton, in contrast, imagined being ‘as remote from Europe as any mediaeval adventurer’.

Scribner’s published In Morocco in October 1920, a month before that year’s presidential election, fought between the Republican Warren Harding and the Democrat James Cox. Reflecting on the global role of the US, Americans considered a variety of questions: should the US engage in activist foreign policies? Should it curb the growing influence of Europe in the Arab provinces of the defunct Ottoman Empire? Or should it retreat from what one historian calls ‘the Wilsonian Moment’? Wharton’s travelogue unabashedly promoted imperialism.

Some reviewers disagreed with her and In Morocco prompted political debate. ‘All the properties of an Arabian Nights tale are here’, wrote Irita Van Doren in the Nation, noting ‘camels and donkeys, white-draped riders, palmetto deserts, camel’s hair tents, and veiled women’. However, she cautioned, Wharton ‘accepts without question the general theory of imperialism’. Wharton did not invent Moroccan clichés, but her high profile and the concurrent growth of US power rendered their use political in a new way. Her descriptions of a backward land called for Western intervention in the Arab world.

Stacy E. Holden is Associate Professor of History at Purdue University and the author of The Politics of Food in Modern Morocco (University Press of Florida, 2015).

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2Ib1o2P

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.