I.

Kaj Sotala has an outstanding review of Unlocking The Emotional Brain; I read the book, and Kaj’s review is better.

He begins:

UtEB’s premise is that much if not most of our behavior is driven by emotional learning. Intense emotions generate unconscious predictive models of how the world functions and what caused those emotions to occur. The brain then uses those models to guide our future behavior. Emotional issues and seemingly irrational behaviors are generated from implicit world-models (schemas) which have been formed in response to various external challenges. Each schema contains memories relating to times when the challenge has been encountered and mental structures describing both the problem and a solution to it.

So in one of the book’s example cases, a man named Richard sought help for trouble speaking up at work. He would have good ideas during meetings, but felt inexplicably afraid to voice them. During therapy, he described his narcissistic father, who was always mouthing off about everything. Everyone hated his father for being a fool who wouldn’t shut up. The therapist conjectured that young Richard observed this and formed a predictive model, something like “talking makes people hate you”. This was overly general: talking only makes people hate you if you talk incessantly about really stupid things. But when you’re a kid you don’t have much data, so you end up generalizing a lot from the few examples you have.

When Richard started therapy, he didn’t consciously understand any of this. He just felt emotions (anxiety) at the thought of voicing his opinion. The predictive model output the anxiety, using reasoning like “if you talk, people will hate you, and the prospect of being hated should make you anxious – therefore, anxiety”, but not any of the intermediate steps. The therapist helped Richard tease out the underlying model, and at the end of the session Richard agreed that his symptoms were related to his experience of his father. But knowing this changed nothing; Richard felt as anxious as ever.

Predictions like “speaking up leads to being hated” are special kinds of emotional memory. You can rationally understand that the prediction is no longer useful, but that doesn’t really help; the emotional memory is still there, guiding your unconscious predictions. What should the therapist do?

Here UtEB dives into the science on memory reconsolidation.

Scientists have known for a while that giving rats the protein synthesis inhibitor anisomycin prevents them from forming emotional memories. You can usually give a rat noise-phobia by pairing a certain noise with electric shocks, but this doesn’t work if the rats are on anisomycin first. Probably this means that some kind of protein synthesis is involved in memory. So far, so plausible.

A 2000 study found that anisomycin could also erase existing phobias in a very specific situation. You had to “activate” the phobia – get the rats thinking about it really hard, maybe by playing the scary noise all the time – and then give them the anisomycin. This suggested that when the memory got activated, it somehow “came loose”, and the brain needed to do some protein synthesis to put it back together again.

Thus the idea of memory reconsolidation: you form a consolidated memory, but every time you activate it, you need to reconsolidate it. If the reconsolidation fails, you lose the memory, or you get a slightly different memory, or something like that. If you could disrupt emotional memories like “speaking out makes you hated” while they’re still reconsolidating, maybe you could do something about this.

Anisomycin is pretty toxic, so that’s out. Other protein synthesis inhibitors are also toxic – it turns out proteins are kind of important for life – so they’re out too. Electroconvulsive therapy actually seems to work pretty well for this – the shock disrupts protein formation very effectively (and the more I think about this, the more implications it seems to have). But we can’t do ECT on everybody who wants to be able to speak up at work more, so that’s also out. And the simplest solution – activating a memory and then reminding the patient that they don’t rationally believe it’s true – doesn’t seem to help; the emotional brain doesn’t speak Rationalese.

The authors of UtEB claim to have found a therapy-based method that works, which goes like this:

First, they tease out the exact predictive model and emotional memory behind the symptom (in Richard’s case, the narrative where his father talked too much and ended up universally hated, and so if Richard talks at all, he too will be universally hated). Then they try to get this as far into conscious awareness as possible (or, if you prefer, have consciousness dig as deep into the emotional schema as possible). They call this “the pro-symptom position” – giving the symptom as much room as possible to state its case without rejecting it. So for example, Richard’s therapist tried to get Richard to explain his unconscious pro-symptom reasoning as convincingly as possible: “My father was really into talking, and everybody hated him. This proves that if I speak up at work, people will hate me too.” She even asked Richard to put this statement on an index card, review it every day, and bask in its compellingness. She asked Richard to imagine getting up to speak, and feeling exactly how anxious it made him, while reviewing to himself that the anxiety felt justified given what happened with his father. The goal was to establish a wide, well-trod road from consciousness to the emotional memory.

Next, they try to find a lived and felt experience that contradicts the model. Again, Rationalese doesn’t work; the emotional brain will just ignore it. But it will listen to experiences. For Richard, this was a time when he was at a meeting, had a great idea, but didn’t speak up. A coworker had the same idea, mentioned it, and everyone agreed it was great, and congratulated the other person for having such an amazing idea that would transform their business. Again, there’s this same process of trying to get as much in that moment as possible, bring the relevant feelings back again and again, create as wide and smooth a road from consciousness to the experience as possible.

Finally, the therapist activates the disruptive emotional schema, and before it can reconsolidate, smashes it into the new experience. So Richard’s therapist makes use of the big wide road Richard built that let him fully experience his fear of speaking up, and asks Richard to get into that frame of mind (activate the fear-of-speaking schema). Then she asks him, while keeping the fear-of-speaking schema in mind, to remember the contradictory experience (coworker speaks up and is praised). Then the therapist vividly describes the juxtaposition while Richard tries to hold both in his mind at once.

And then Richard was instantly cured, and never had any problems speaking up at work again. His coworkers all applauded, and became psychotherapists that very day. An eagle named “Psychodynamic Approach” flew into the clinic and perched atop the APA logo and shed a single tear. Coherence Therapy: Practice Manual And Training Guide was read several times, and God Himself showed up and enacted PsyD prescribing across the country. All the cognitive-behavioralists died of schizophrenia and were thrown in the lake of fire for all eternity.

This is, after all, a therapy book.

II.

I like UtEB because it reframes historical/purposeful accounts of symptoms as aspects of a predictive model. We already know the brain has an unconscious predictive model that it uses to figure out how to respond to various situations and which actions have which consequences. In retrospect, this framing perfectly fits the idea of traumatic experiences having outsized effects. Tack on a bit about how the model is more easily updated in childhood (because you’ve seen fewer other things, so your priors are weaker), and you’ve gone a lot of the way to traditional models of therapy.

But I also like it because it helps me think about the idea of separation/noncoherence in the brain. Richard had his schema about how speaking up makes people hate you. He also had lots of evidence that this wasn’t true, both rationally (his understanding that his symptoms were counterproductive) and experientially (his story about a coworker proposing an idea and being accepted). But the evidence failed to naturally propagate; it didn’t connect to the schema that it should have updated. Only after the therapist forced the connection did the information go through. Again, all of this should have been obvious – of course evidence doesn’t propagate through the brain, I was writing posts ten years ago about how even a person who knows ghosts don’t exist will be afraid to stay in an old supposedly-haunted mansion at night with the lights off. But UtEB’s framework helps snap some of this into place.

UtEB’s brain is a mountainous landscape, with fertile valleys separated by towering peaks. Some memories (or pieces of your predictive model, or whatever) live in each valley. But they can’t talk to each other. The passes are narrow and treacherous. They go on believing their own thing, unconstrained by conclusions reached elsewhere.

Consciousness is a capital city on a wide plain. When it needs the information stored in a particular valley, it sends messengers over the passes. These messengers are good enough, but they carry letters, not weighty tomes. Their bandwidth is atrocious; often they can only convey what the valley-dwellers think, and not why. And if a valley gets something wrong, lapses into heresy, as often as not the messengers can’t bring the kind of information that might change their mind.

Links between the capital and the valleys may be tenuous, but valley-to-valley trade is almost non-existent. You can have two valleys full of people working on the same problem, for years, and they will basically never talk.

Sometimes, when it’s very important, the king can order a road built. The passes get cleared out, high-bandwidth communication to a particular communication becomes possible. If he does this to two valleys at once, then they may even be able to share notes directly, each passing through the capital to get to each other. But it isn’t the norm. You have to really be trying.

This ended out a little more flowery than I expected, but I didn’t start thinking this way because it was poetic. I started thinking this way because of this:

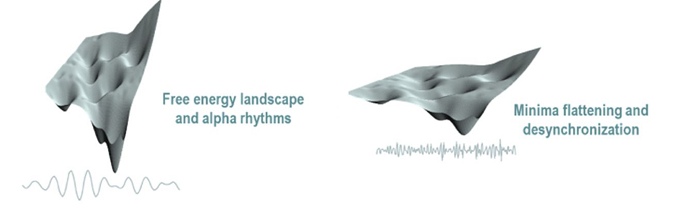

Frequent SSC readers will recognize this as from Figure 1 of Friston and Carhart-Harris’ REBUS And The Anarchic Brain: Toward A Unified Model Of The Brain Action Of Psychedelics, which I review here. The paper describes it as “the curvature of the free-energy landscape that contains neuronal dynamics. Effectively, this can be thought of as a flattening of local minima, enabling neuronal dynamics to escape their basins of attraction and—when in flat minima—express long-range correlations and desynchronized activity.”

Moving back a step: the paper is trying to explain what psychedelics do to the brain. It theorizes that they weaken high-level priors (in this case, you can think of these as the tendency to fit everything to an existing narrative), allowing things to be seen more as they are:

A corollary of relaxing high-level priors or beliefs under psychedelics is that ascending prediction errors from lower levels of the system (that are ordinarily unable to update beliefs due to the top-down suppressive influence of heavily-weighted priors) can find freer register in conscious experience, by reaching and impressing on higher levels of the hierarchy. In this work, we propose that this straightforward model can account for the full breadth of subjective phenomena associated with the psychedelic experience.

These ascending prediction errors (ie noticing that you’re wrong about something) can then correct the high-level priors (ie change the narratives you tell about your life):

The ideal result of the process of belief relaxation and revision is a recalibration of the relevant beliefs so that they may better align or harmonize with other levels of the system and with bottom-up information—whether originating from within (e.g., via lower-level intrinsic systems and related interoception) or, at lower doses, outside the individual (i.e., via sensory input or extroception). Such functional harmony or realignment may look like a system better able to guide thought and behavior in an open, unguarded way (Watts et al., 2017; Carhart-Harris et al., 2018b).

This makes psychedelics a potent tool for psychotherapy:

Consistent with the model presented in this work, overweighted high-level priors can be all consuming, exerting excessive influence throughout the mind and brain’s (deep) hierarchy. The negative cognitive bias in depression is a good example of this (Beck, 1972), as are fixed delusions in psychosis (Sterzer et al., 2018).25 In this paper, we propose that psychedelics can be therapeutically effective, precisely because they target the high levels of the brain’s functional hierarchy, primarily affecting the precision weighting of high-level priors or beliefs. More specifically, we propose that psychedelics dose-dependently relax the precision weighting of high-level priors (instantiated by high-level cortex), and in so doing, open them up to an upsurge of previously suppressed bottom-up signaling (e.g., stemming from limbic circuitry). We further propose that this sensitization of high-level priors means that more information can impress on them, potentially inspiring shifts in perspective, felt as insight. One might ask whether relaxation followed by revision of high-level priors or beliefs via psychedelic therapy is easy to see with functional (and anatomic) brain imaging. We presume that it must be detectable, if the right questions are asked in the right way.

Am I imagining this, or are Friston + Carhart-Harris and Unlocking The Emotional Brain getting at the same thing?

Both start with a piece of a predictive model (= high-level prior) telling you something that doesn’t fit the current situation. Both also assume you have enough evidence to convince a rational person that the high-level prior is wrong, or doesn’t apply. But you don’t automatically smash the prior and the evidence together and perform an update. In UtEB‘s model, the update doesn’t happen until you forge conscious links to both pieces of information and try to hold them in consciousness at the same time. In F+CH’s model, the update doesn’t happen until you take psychedelics which make the high-level prior lose some of its convincingness. UtEB is trying to laboriously build roads through mountains; F+CH are trying to cast a magic spell that makes the mountains temporarily vanish. Either way, you get communication between areas that couldn’t communicate before.

III.

Why would mental mountains exist? If we keep trying to get rid of them, through therapy or psychedelics, or whatever, then why not just avoid them in the first place?

Maybe generalization is just hard (thanks to MC for this idea). Suppose Goofus is mean to you. You learn Goofus is mean; if this is your first social experience, maybe you also learn that the world is mean and people have it out for you. Then one day you meet Gallant, who is nice to you. Hopefully the system generalizes to “Gallant is nice, Goofus is still mean, people in general can go either way”.

But suppose one time Gallant is just having a terrible day, and curses at you, and that time he happens to be wearing a red shirt. You don’t want to overfit and conclude “Gallant wearing a red shirt is mean, Gallant wearing a blue shirt is nice”. You want to conclude “Gallant is generally nice, but sometimes slips and is mean.”

But any algorithm that gets too good at resisting the temptation to separate out red-shirt-Gallant and blue-shirt-Gallant risks falling into the opposite failure mode where it doesn’t separate out Gallant and Goofus. It would just average them out, and conclude that people (including both Goofus and Gallant) are medium-niceness.

And suppose Gallant has brown eyes, and Goofus green eyes. You don’t want your algorithm to overgeneralize to “all brown-eyed people are nice, and all green-eyed people are mean”. But suppose the Huns attack you. You do want to generalize to “All Huns are dangerous, even though I can keep treating non-Huns as generally safe”. And you want to do this as quickly as possible, definitely before you meet any more Huns. And the quicker you are to generalize about Huns, the more likely you are to attribute false significance to Gallant’s eye color.

The end result is a predictive model which is a giant mess, made up of constant “This space here generalizes from this example, except this subregion, which generalizes from this other example, except over here, where it doesn’t, and definitely don’t ever try to apply any of those examples over here.” Somehow this all works shockingly well. For example, I spent a few years in Japan, and developed a good model for how to behave in Japanese culture. When I came back to the United States, I effortlessly dropped all of that and went back to having America-appropriate predictions and reflexive actions (except for an embarrassing habit of bowing whenever someone hands me an object, which I still haven’t totally eradicated).

In this model, mental mountains are just the context-dependence that tells me not to use my Japanese predictive model in America, and which prevents evidence that makes me update my Japanese model (like “I notice subways are always on time”) from contaminating my American model as well. Or which prevent things I learn about Gallant (like “always trust him”) from also contaminating my model of Goofus.

There’s actually a real-world equivalent of the “red-shirt-Gallant is bad, blue-shirt-Gallant is good” failure mode. It’s called “splitting”, and you can find it in any psychology textbook. Wikipedia defines it as “the failure in a person’s thinking to bring together the dichotomy of both positive and negative qualities of the self and others into a cohesive, realistic whole.”

In the classic example, a patient is in a mental hospital. He likes his doctor. He praises the doctor to all the other patients, says he’s going to nominate her for an award when he gets out.

Then the doctor offends the patient in some way – maybe refuses one of his requests. All of a sudden, the doctor is abusive, worse than Hitler, worse than Mengele. When he gets out he will report her to the authorities and sue her for everything she owns.

Then the doctor does something right, and it’s back to praise and love again.

The patient has failed to integrate his judgments about the doctor into a coherent whole, “doctor who sometimes does good things but other times does bad things”. It’s as if there’s two predictive models, one of Good Doctor and one of Bad Doctor, and even though both of them refer to the same real-world person, the patient can only use one at a time.

Splitting is most common in borderline personality disorder. The DSM criteria for borderline includes splitting (there defined as “a pattern of unstable and intense interpersonal relationships characterized by alternating between extremes of idealization and devaluation”). They also include things like “markedly and persistently unstable self-image or sense of self”, and “affective instability due to a marked reactivity of mood”, which seem relevant here too.

Some therapists view borderline as a disorder of integration. Nobody is great at having all their different schemas talk to each other, but borderlines are atrocious at it. Their mountains are so high that even different thoughts about the same doctor can’t necessarily talk to each other and coordinate on a coherent position. The capital only has enough messengers to talk to one valley at a time. If tribesmen from the Anger Valley are advising the capital today, the patient becomes truly angry, a kind of anger that utterly refuses to listen to any counterevidence, an anger pure beyond your imagination. If they are happy, they are purely happy, and so on.

About 70% of people diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder (previously known as multiple personality disorder) have borderline personality disorder. The numbers are so high that some researchers are not even convinced that these are two different conditions; maybe DID is just one manifestation of borderline, or especially severe borderline. Considering borderline as a failure of integration, this makes sense; DID is total failure of integration. People in the furthest mountain valleys, frustrated by inability to communicate meaningfully with the capital, secede and set up their own alternative provincial government, pulling nearby valleys into their new coalition. I don’t want to overemphasize this; most popular perceptions of DID are overblown, and at least some cases seem to be at least partly iatrogenic. But if you are bad enough at integrating yourself, it seems to be the sort of thing that can happen.

In his review, Kaj relates this to Internal Family Systems, a weird form of therapy where you imagine your feelings as people/entities and have discussions with them. I’ve always been skeptical of this, because feelings are not, in fact, people/entities, and it’s unclear why you should expect them to answer you when you ask them questions. And in my attempts to self-test the therapy, indeed nobody responded to my questions and I was left feeling kind of silly. But Kaj says:

As many readers know, I have been writing a sequence of posts on multi-agent models of mind. In Building up to an Internal Family Systems model, I suggested that the human mind might contain something like subagents which try to ensure that past catastrophes do not repeat. In subagents, coherence, and akrasia in humans, I suggested that behaviors such as procrastination, indecision, and seemingly inconsistent behavior result from different subagents having disagreements over what to do.

As I already mentioned, my post on integrating disagreeing subagents took the model in the direction of interpreting disagreeing subagents as conflicting beliefs or models within a person’s brain. Subagents, trauma and rationality further suggested that the appearance of drastically different personalities within a single person might result from unintegrated memory networks, which resist integration due to various traumatic experiences.

This post has discussed UtEB’s model of conflicting emotional schemas in a way which further equates “subagents” with beliefs – in this case, the various schemas seem closely related to what e.g. Internal Family Systems calls “parts”. In many situations, it is probably fair to say that this is what subagents are.

This is a model I can get behind. My guess is that in different people, the degree to which mental mountains form a barrier will cause the disconnectedness of valleys to manifest as anything from “multiple personalities”, to IFS-findable “subagents”, to UtEB-style psychiatric symptoms, to “ordinary” beliefs that don’t cause overt problems but might not be very consistent with each other.

IV.

This last category forms the crucial problem of rationality.

One can imagine an alien species whose ability to find truth was a simple function of their education and IQ. Everyone who knows the right facts about the economy and is smart enough to put them together will agree on economic policy.

But we don’t work that way. Smart, well-educated people believe all kinds of things, even when they should know better. We call these people biased, a catch-all term meaning something that prevents them from having true beliefs they ought to be able to figure out. I believe most people who don’t believe in anthropogenic climate change are probably biased. Many of them are very smart. Many of them have read a lot on the subject (empirically, reading more about climate change will usually just make everyone more convinced of their current position, whatever it is). Many of them have enough evidence that they should know better. But they don’t.

(again, this is my opinion, sorry to those of you I’m offending. I’m sure you think the same of me. Please bear with me for the space of this example.)

Compare this to Richard, the example patient mentioned above. Richard had enough evidence to realize that companies don’t hate everyone who speaks up at meetings. But he still felt, on a deep level, like speaking up at meetings would get him in trouble. The evidence failed to connect to the emotional schema, the part of him that made the real decisions. Is this the same problem as the global warming case? Where there’s evidence, but it doesn’t connect to people’s real feelings?

(maybe not: Richard might be able to say “I know people won’t hate me for speaking, but for some reason I can’t make myself speak”, whereas I’ve never heard someone say “I know climate change is real, but for some reason I can’t make myself vote to prevent it.” I’m not sure how seriously to take this discrepancy.)

In Crisis of Faith, Eliezer Yudkowsky writes:

Many in this world retain beliefs whose flaws a ten-year-old could point out, if that ten-year-old were hearing the beliefs for the first time. These are not subtle errors we’re talking about. They would be child’s play for an unattached mind to relinquish, if the skepticism of a ten-year-old were applied without evasion…we change our minds less often than we think.

This should scare you down to the marrow of your bones. It means you can be a world-class scientist and conversant with Bayesian mathematics and still fail to reject a belief whose absurdity a fresh-eyed ten-year-old could see. It shows the invincible defensive position which a belief can create for itself, if it has long festered in your mind.

What does it take to defeat an error that has built itself a fortress?

He goes on to describe how hard this is, to discuss the “convulsive, wrenching effort to be rational” that he thinks this requires, the “all-out [war] against yourself”. Some of the techniques he mentions explicitly come from psychotherapy, others seem to share a convergent evolution with it.

The authors of UtEB stress that all forms of therapy involve their process of reconsolidating emotional memories one way or another, whether they know it or not. Eliezer’s work on crisis of faith feels like an ad hoc form of epistemic therapy, one with a similar goal.

Here, too, there is a suggestive psychedelic connection. I can’t count how many stories I’ve heard along the lines of “I was in a bad relationship, I kept telling myself that it was okay and making excuses, and then I took LSD and realized that it obviously wasn’t, and got out.” Certainly many people change religions and politics after a psychedelic experience, though it’s hard to tell exactly what part of the psychedelic experience does this, and enough people end up believing various forms of woo that I hesitate to say it’s all about getting more rational beliefs. But just going off anecdote, this sometimes works.

Rationalists wasted years worrying about various named biases, like the conjunction fallacy or the planning fallacy. But most of the problems we really care about aren’t any of those. They’re more like whatever makes the global warming skeptic fail to connect with all the evidence for global warming.

If the model in Unlocking The Emotional Brain is accurate, it offers a starting point for understanding this kind of bias, and maybe for figuring out ways to counteract it.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2Dm487G

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.