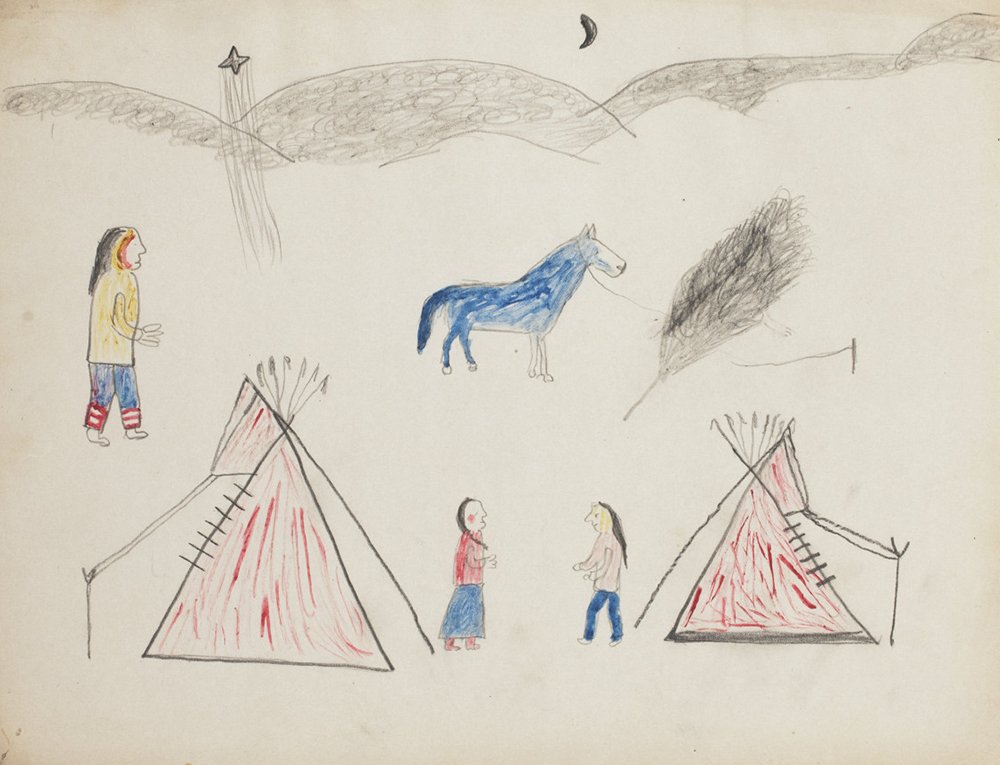

First there was but a speck. From out of the immense flat a figure emerged slowly, as if floating, gleaming white in hot air. The two men on the hill saw that it was a woman and that she was wakȟáŋ, holy, so they waited. As the woman grew larger, they saw that she was carrying a bundle and that her hair covered her body like a robe. One of the men lowered his eyes, but the other kept staring at her. She saw that he desired her and asked him to come near. A cloud concealed them. When it dissolved, the woman stood alone, a pile of bones and snakes at her feet. She turned to the other man and told him to go back to his village and have his people prepare a lodge for her.

When she arrived four days later, the village was ready. She entered a large medicine tipi, singing,

With visible breath I am walking.

A voice I am sending as I walk.

In a sacred manner I am walking.

With visible tracks I am walking.

In a sacred manner I am walking.

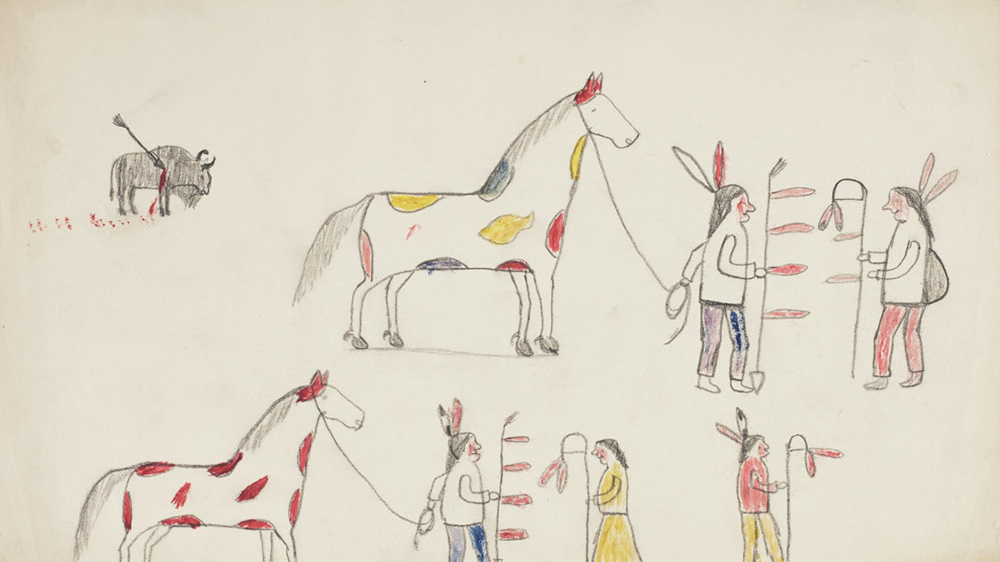

She circled the lodge sunwise and instructed the people to build an altar of red earth with a buffalo skull in the center. She opened her bundle and took out a pipe, holding its bowl with her left hand and the stem with her right. She walked around the lodge four times, evoking the great sun and “the circle without end, the sacred hoop, the road of life.” She lit the pipe. Its red stone bowl, she explained, signified the earth and the buffalo whose four legs stood for the four directions of the universe and the four ages of man. The smoke rising from the bowl was the living breath of Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka, the Great Spirit, and the wooden stem stood for all plants growing on the earth. An attached fan of twelve feathers stood for the eagle and all the birds of the air.

Ptesáŋwiŋ, the White Buffalo Calf Woman, had brought the gift of the sacred Buffalo Calf Pipe, Ptehíŋčala Čhaŋnúŋpa, by which Lakotas would live thereon. With the pipe they would “walk like a living prayer,” their feet resting on the ground and the pipestem reaching to the sky and their bodies “a living bridge between the Sacred Beneath and the Sacred Above.” The pipe, the woman said, was a gift from Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka, who smiled upon them because they had become one with the universe: “earth, sky, all living things, the two-legged, the four-legged, the winged ones, the trees, the grasses. Together with the people, they are all related, one family. The pipe holds them all together.”

It would also hold Lakotas together. The surface of the bowl, the White Buffalo Calf Woman revealed, was marked with seven incised circles, standing for seven ceremonies that would guide Lakotas to live well. She taught them the first, the Sacred Pipe Ceremony, and promised to reveal the others in time. Although she would soon leave, she would return. She would look upon them always. The White Buffalo Calf Woman had come to Lakotas at a time of famine and confusion. The two Lakota men who first met her were hunters, sent out by their chief to find bison for his starving village. Lakotas were starving because their lives had no structure or meaning. “There was nothing sacred before the pipe came,” Left Heron, an Oglala elder, recounted later. “There was no social organization and the people ran around the prairie like so many wild animals.” The pipe changed all that. “With this pipe you will be bound to all your relatives,” the holy woman announced. “By this pipe the tribe shall live.” Instead of as strangers, Lakotas would embrace one another as kin, which would give their lives order. The pipe also established a pact between humans and buffaloes. “I represent the Buffalo tribe,” the woman said. “When you are in need of buffalo meat, smoke this pipe and ask for what you need and it shall be granted you.” When, after several days, it became time for the White Buffalo Calf Woman to leave, she turned herself into a white buffalo calf. She bowed to the four sacred directions and vanished, leaving behind a promise of order and plenty.

The story of the White Buffalo Calf Woman is ancient, reaching back to a time when Lakotas first emerged as a distinct, self-aware people. The story acquired new urgency in the early nineteenth century, when Lakotas made their second concerted push into the West, this time from the Missouri Valley, their home for more than half a century. It marked the beginning of a new phase in their history, a phase that saw their expansion becoming increasingly intertwined with the American expansion. It was a phase that centered to a remarkable degree on the Black Hills.

Lakotas had frequented the Black Hills from their Mníšoše homelands since the late eighteenth century, drawn by the region’s spiritual primacy, unique climate, and reliable bison herds. The White Buffalo Calf Woman appeared to them in Pahá Sápa, the Black Hills, when the buffalo were scarce and people were suffering. But Pahá Sápa became known as North America’s paramount bison hunting range, the place where hunters could find game even when herds were failing everywhere else. This was the gift of the White Buffalo Calf Woman—and of the area’s higher elevation that caught greater rainfall and, consequently, offered more pasture and bison.

Lakotas responded to Pahá Sápa’s seductive pull. Every year they hunted in the western grasslands, following the protective passageways of water and trees toward the Pahá Sápa two hundred miles away. On these western excursions they may have joined forces with Cheyennes who had already made the western plains home and regularly hunted in the Black Hills. Pahá Sápa loomed ever larger for Lakotas as a source of prosperity and rebirth, but they were beyond their control.

The Black Hills had been inhabited since time immemorial, the thousand-year-old rock art on its sandstone boulders a testimony of a deep human connection to the place. People had prayed, hunted, and farmed on the hills, which stood out like a lush island in a dry sea of grass. But in the late eighteenth century, as the horse frontier inched northward across the western plains, the Black Hills became nomads’ domain. Several newly equestrian people vied for control of the region. Slowly, in the early years of the nineteenth century, Cheyennes emerged as the dominant group. Cheyennes formed an alliance with the Arapahos and made the Black Hills theirs.

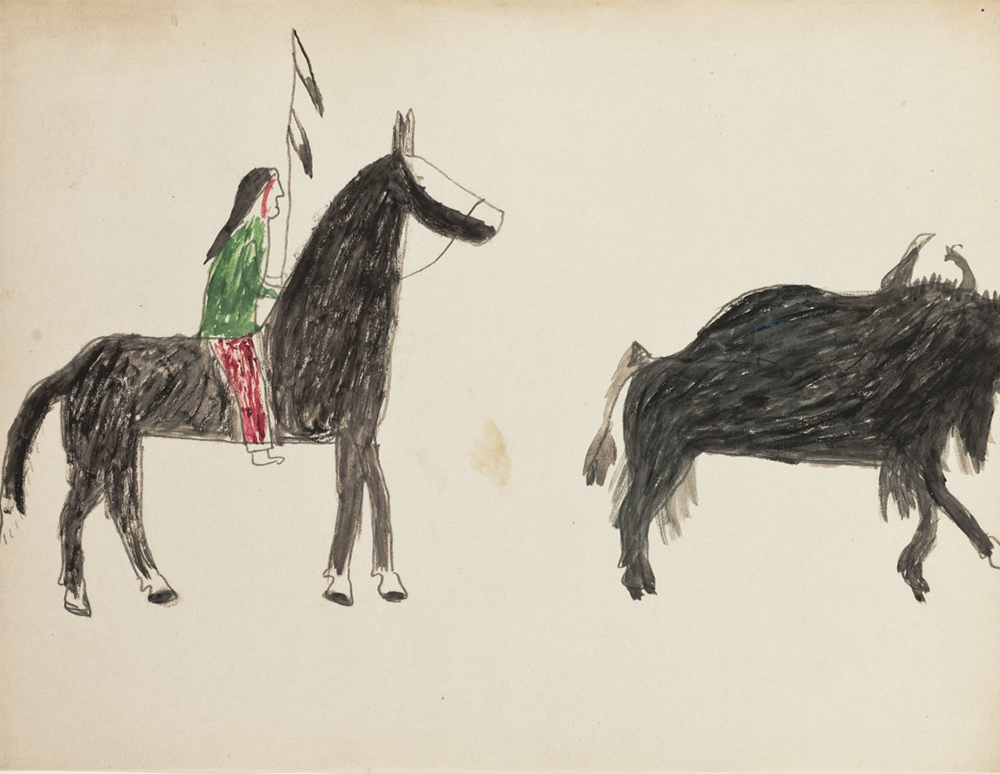

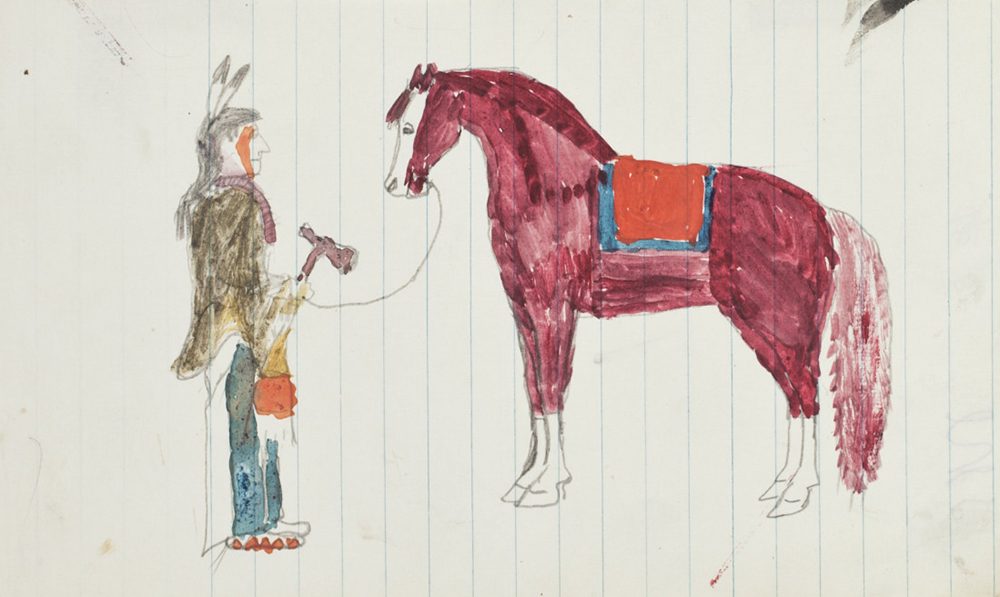

Lakotas had access to Pahá Sápa through their own tightening alliance with Cheyennes, and the hills and the buffalo plains around the Black Hills beckoned them to the West. Getting there was, in the end, an intensely mundane matter of acquiring the necessary technology: procuring horses, tending them, and building up substantial herds. This happened, gradually, in the course of the 1820s and 1830s, when Lakotas amassed enough mounts for large-scale equestrian warfare.

Prince Maximilian, the German explorer-traveler, observed the equestrian takeoff in its early stages, when successful individuals “frequently possess from thirty to forty horses” and could put all their relatives on horseback. Horses translated into mobility and power, fueling western expansion. For decades the Mníšoše had been the home of Lakotas and seat of their power; now it became staging ground for increasingly ambitious western expeditions. Geography itself seemed to invite Lakotas in. From the Mníšoše’s west bank a string of rivers pointed like fingers toward unprecedented animal wealth and spiritual fulfillment beyond the horizon, pulling them in. Eight great tributaries—the White, Bad, Cheyenne, Moreau, Grand, Cannonball, Heart, and Knife—all flush with riparian forests, veined the western plains, providing all the means necessary for a grand leap toward the life-affirming Pahá Sápa.

The eight roads were not activated all at once. Oglalas and Sicangus were the first to turn west, ascending the White and Bad, which offered reliable water and wood, serving as superb passageways. As they inched upriver, they clashed with Kiowas and Crows, pushing the former to the south and the latter to the west. Sicangus joined forces with Cheyennes against the Kiowas, while Oglalas spearheaded campaigns against Crows under the leadership of Bull Bear, whose boldness and resolve seemed to have given their operations particular sharpness. By the late 1820s Crows had retreated from the Black Hills into the Powder River country a hundred miles to the west, and Oglalas and Sicangus established themselves on Pahá Sápa’s eastern side. By that time Sans Arcs, Minneconjous, Two Kettles, Sihasapas, and Hunkpapas had also begun to shift west, establishing the Cheyenne and Grand as entryways.

Lakotas had turned west, decisively, but they remained people of river valleys first and people of the plains second. They ventured into the western grasslands and Pahá Sápa from multiple points along timbered river valleys and moved back regularly along those same valleys to the Mníšoše, which remained vital to their cosmology and economy. Essentially protrusions of the Missourian riparian woodlands, the White, Bad, Cheyenne, and other tributaries provided Lakotas with safe and familiar pathways into the West. When they began pulling away from the Missouri, they were not so much casting themselves loose on the open plains but extending their old riverland world into the West.

This tripartite pattern—a trunk line in the east, an elevated, magnet-like anchor in the west, and a row of arterials in between—formed the core of the Lakota world from the 1830s onward. It was in those three places where Lakotas spent most of their time—cooking, eating, sleeping, socializing, smoking, praying, raising children, tending horses, preparing hides, making clothes, tools, and weapons—and where most of them entered and left this world. This was the homeland Lakotas would defend against invaders and, when needed, expand.

The western tributaries were keys to land and wealth and power, but they were also conduits into a perilous new world, for they carried Lakotas toward greater aridity. The western Great Plains lie in a long rain shadow cast by the Rocky Mountains. Pacific winds pump moist maritime air eastward, but the air sheds much of its moisture while climbing up the Rockies. The shadow effect is strongest in the west, the 98th meridian marking a default line where evaporation exceeds precipitation and the soil starts to go dry. The grass cover reflects this, becoming shorter toward the west. Around the 105th meridian densely tufted blue grama and buffalo grasses become dominant and the plant canopy shrinks down to a few inches. The bison had adapted over the millennia to these semi-arid conditions, thriving on the stunted shortgrasses that retained protein in their dry stalks, making them ideal winter forage. Tens of millions of them lived in the plains, their huge bodies a hunter’s delight.

That was when the Black Hills began to loom large in a material sense. When severe droughts struck the grasslands, the bison tended to seek relief in the high-altitude microclimate around the Black Hills where summers were cooler, rainfall higher, and pasture more lavish. Lakotas did the same. This introduced a new dimension to Pahá Sápa’s allure: it became a sanctuary and a meat pack. Lakotas gathered there to sit out droughts and subsist on buffaloes that seemed to give themselves up—just like the White Buffalo Calf Woman had promised.

The control of Pahá Sápa became a spiritual and material imperative without which nothing in the world was secure—not its unearthly bounties, not the hunt, not the survival of Lakotas as a people. Hand paintings on Pahá Sápa’s rocky planes—red spots marking slain enemies—bespeak of the violent struggle that turned the mountain range into an exclusive domain of Lakotas and their Cheyenne and Arapaho allies. By the late 1820s Lakotas were wintering in Pahá Sápa.

The Black Hills belonged to them.

Excerpted from Lakota America: A New History of Indigenous Power, by Pekka Hämäläinen, published this week by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2019 by Pekka Hämäläinen. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2Wi5Ak5

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.