Alexis Beingessner’s Text Rendering Hates You, published exactly a month ago today, hits very close to my heart.

Back in 2017, I was building a rich text editor in the browser. Unsatisfied with existing libraries that used ContentEditable, I thought to myself “hey, I’ll just reimplement text selection myself! How difficult could it possibly be?” I was young. Naive. I estimated it would take two weeks. In reality, attempting to solve this problem would consume several years of my life, and even landed me a full time job for a year implementing text editing for a new operating system.

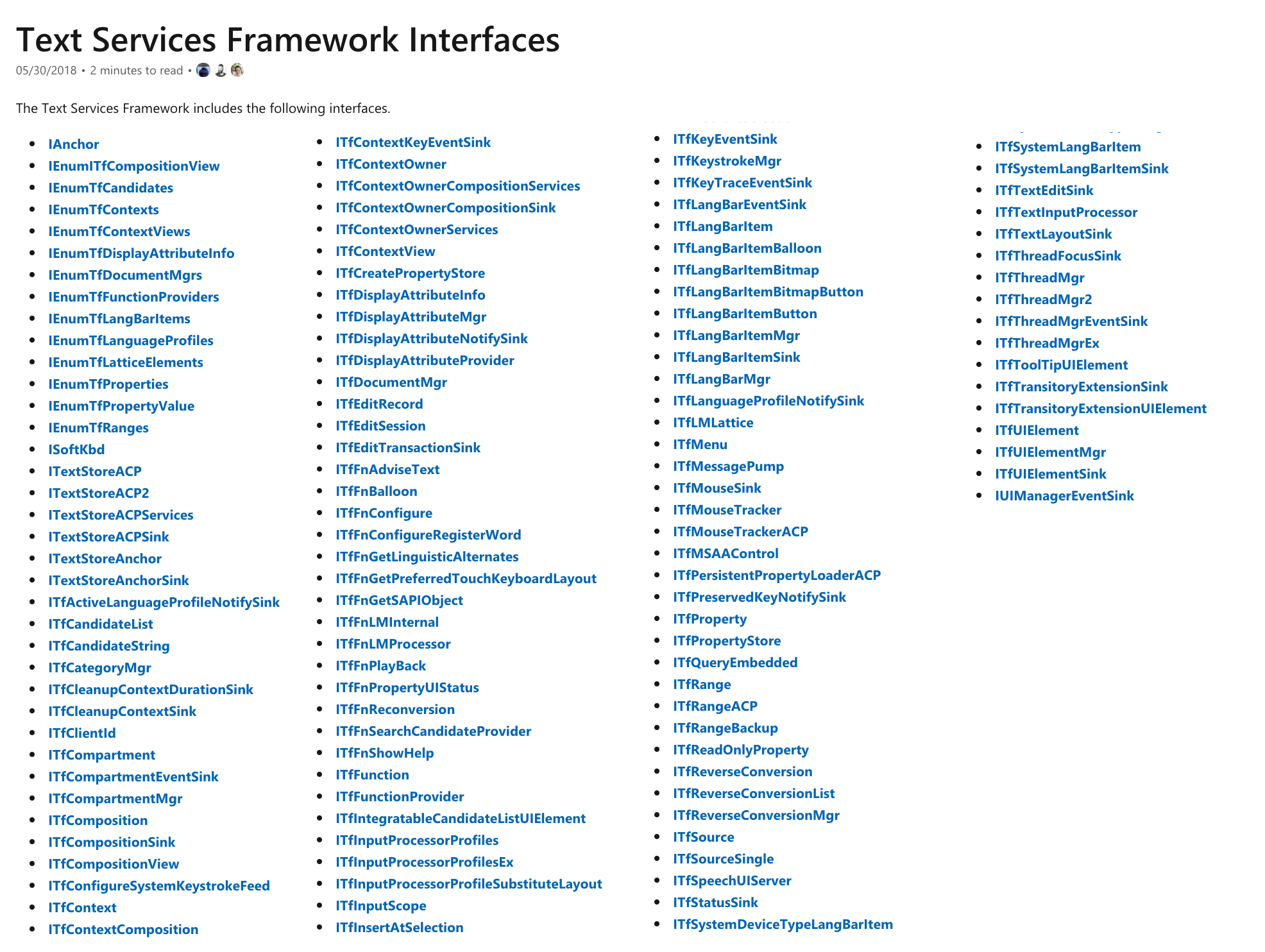

While on the job, I was lucky enough to learn from mentors who had lots of experience in this field. I heard many, many horror stories, including of one person maintaining a Windows application that had a custom text field implementation. They wanted to upgrade from the legacy Windows text input API to a newer version. Let’s look at the interface list for that newer version:

That’s right, the Windows text input APIs contain 128 interfaces. I’m pretty sure there are also eight (8!) different types of locks to fix concurrency issues, although I honestly haven’t read their documentation, so don’t quote me on that. Anyway, this engineer I heard about spent a year and a half (full-time!) attempting the upgrade, and in the end, their efforts ended in failure. They ended up staying on the legacy API.

Text input is difficult.

Alexis already touches on selection in a couple places, but as she mentions in her article, her experience is with working on text rendering. From the perspective of somebody who worked on the editing side of things, I have a few pain points to add.

Vertical Cursor Movement

I already covered it in a previous post, but we can quickly reiterate here.

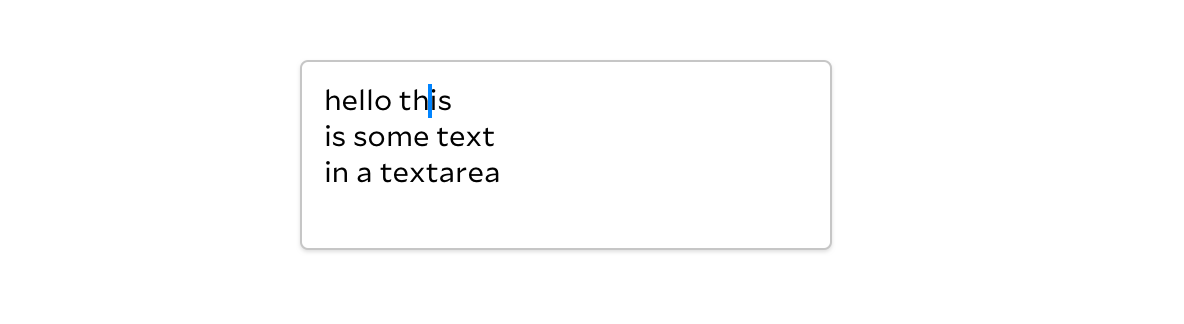

In this example, if the user presses up, the caret will go to the beginning of the line, before “hello”. This is pretty reasonable so far. However, if the user presses up and then down, the caret will first jump before “hello”, and then after the word “some”.

This may seem unintuitive. Why does it jump rightward? Well, each caret remembers an x-position in pixels that is used for vertical movements, and this position is only updated when the user presses left or right, not up and down. This is the same behavior that prevents carets from migrating left when vertically moving past short lines.

Affinity

Ok, so we now know that a text selection has two chunks of state, the byte offsets of its position inside the string and the x-position in pixels mentioned above. Problem solved? Well, no.

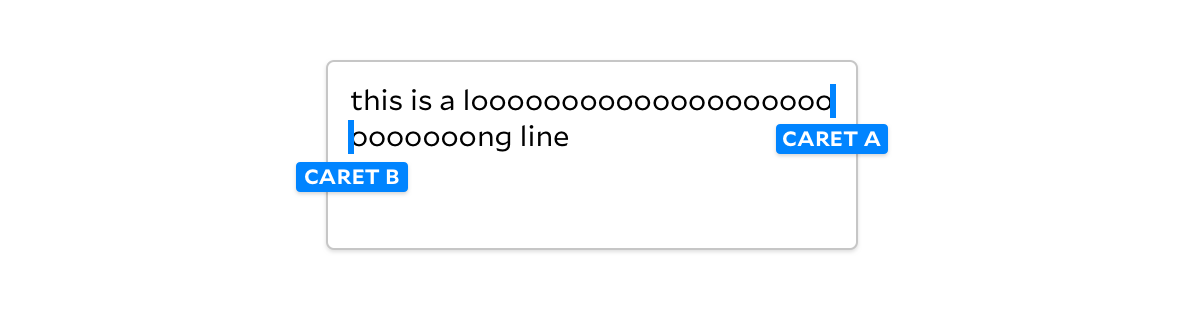

Let’s look at two caret positions on a very long line:

Since “loooooooooong” is a single word, the two caret positions have exactly the same byte offset in the string. There’s no newline character between them, since the line is soft wrapped. Our carets will need an extra bit that tells them which line to tend towards. Most systems call this bit “affinity”. This same bit is also used in mixed bidirectional text, which we’ll get to in a moment.

Emoji Modifiers

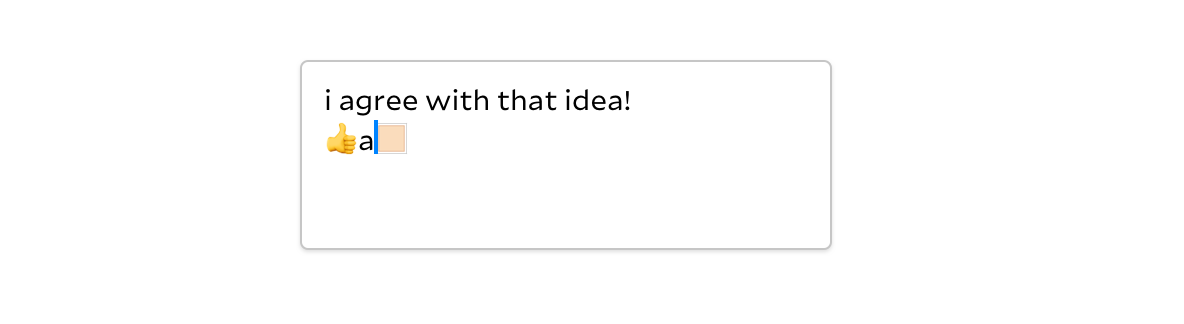

Let’s say I’m sending a message to my friend. To emphasize my excitement, I want to add in a fun lil emoji. I fill a textarea with a thumbs up, the letter a, and an emoji skin tone modifier. It looks like this:

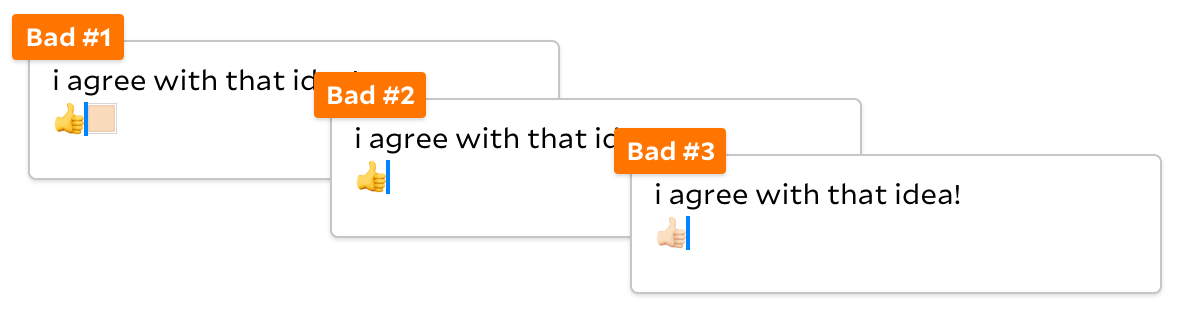

Whoops, I didn’t mean to put the a there. I position the caret after the a and press backspace. What happens? I’ve seen several outcomes, depending on the editor.

- Bad #1 may look correct. But this is what happens in a text editor that has outdated emoji rendering support, like Sublime Text. This is bad because a light skin tone thumbs up emoji is encoded as the yellow thumbs up emoji immediately followed by the light skin tone modifier. Byte-wise, this should be rendered as a single emoji. Even if I copy-pasted one from another application, it would still be rendered incorrectly like this.

- Bad #2 is what Chrome 77 does in the address bar. Not on web pages, just the address bar. This is not a rendering problem, since copy-pasting a emoji with a skin tone works. Instead, Chrome deletes the

a, and then noticing that theais modified by a skin tone, deletes the skin tone too. Whoops. - Bad #3 is “correct” according to the Unicode spec in that the two emoji merge into one. But it’s pretty confusing for users, and bytewise, our caret has to move in order to not be stuck halfway inside a single emoji.

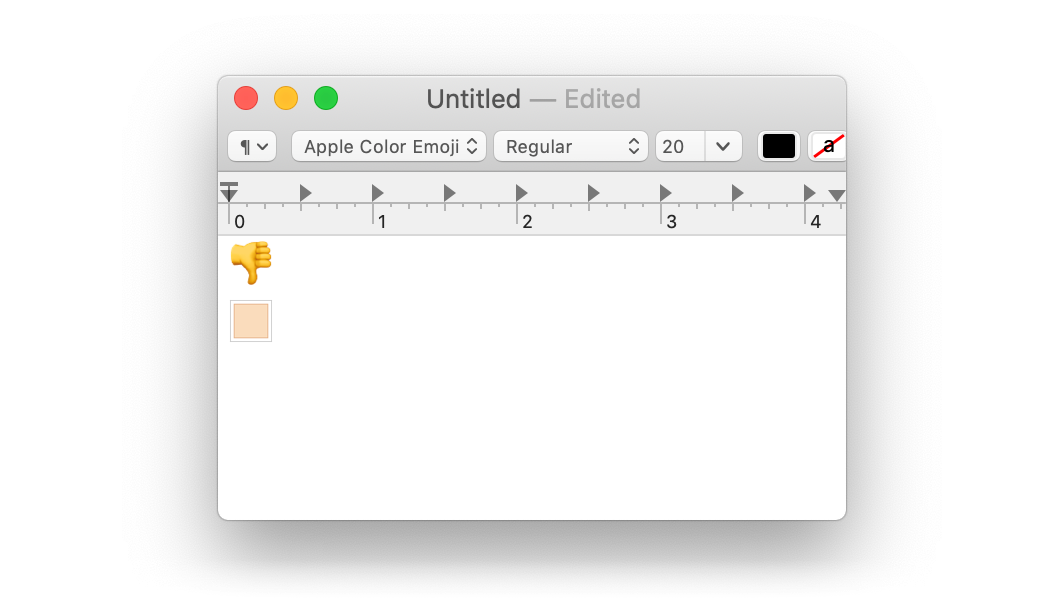

Those options are all bad, so you’re probably hoping there’s some fourth option. There is! Many editors, like TextEdit, won’t even allow us to put a caret after the a, since the skin tone modifier is treated as a single unit with its previous character. This makes sense in the emoji context, and even works alright for this a. However, what happens when the emoji modifier is the first character on a line?

The emoji modifier is now modifying the newline character. TextEdit won’t let us place a caret at the start of the second line! I’d personally consider this solution “also bad”.

You also may have noticed that the thumbs up has switched to a thumbs down. I changed that myself to reflect my feelings about this whole situation.

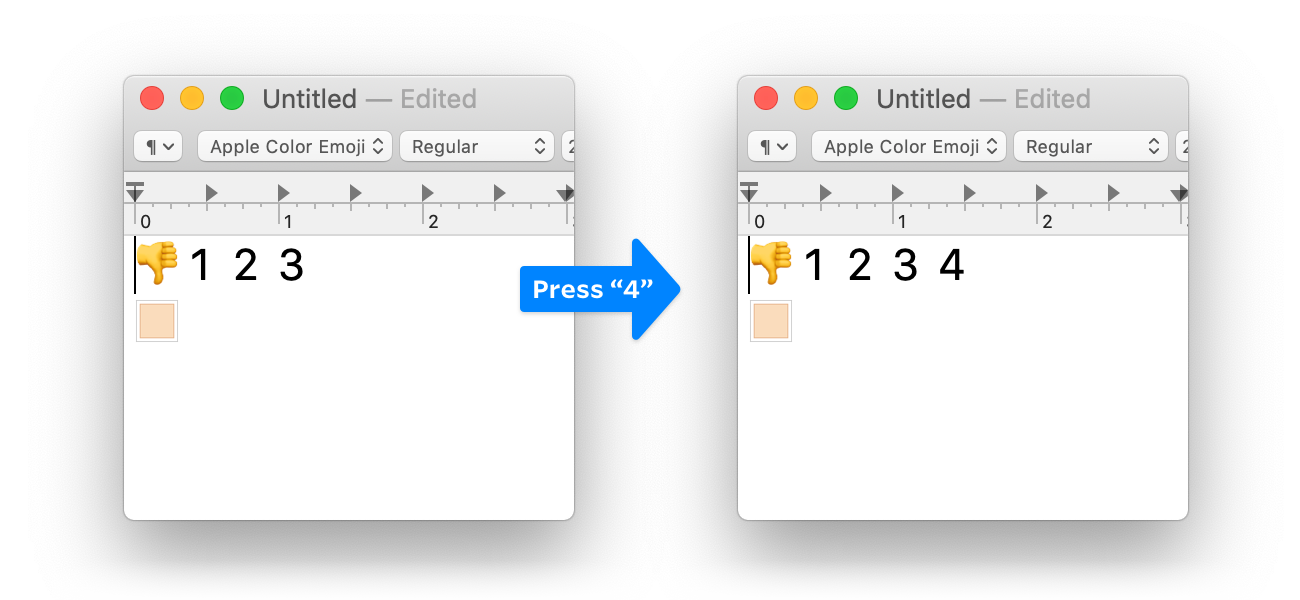

As an aside, TextEdit specifically makes carets on the first line very buggy. For instance, guess what happens if I press 4 here?

Yup. You also may think there are spaces between those numbers. There aren’t.

Bidirectional Text

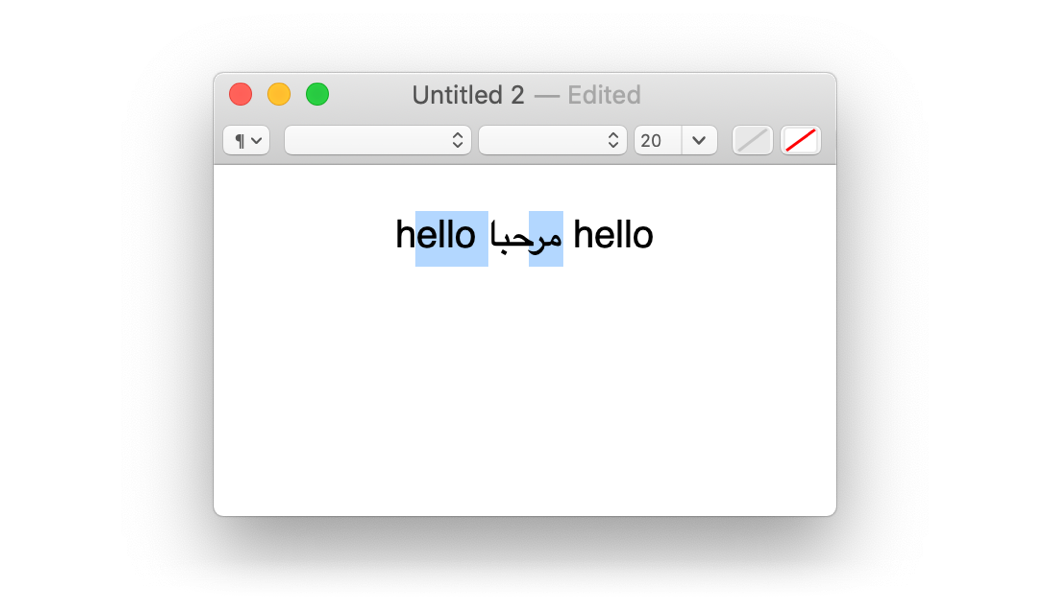

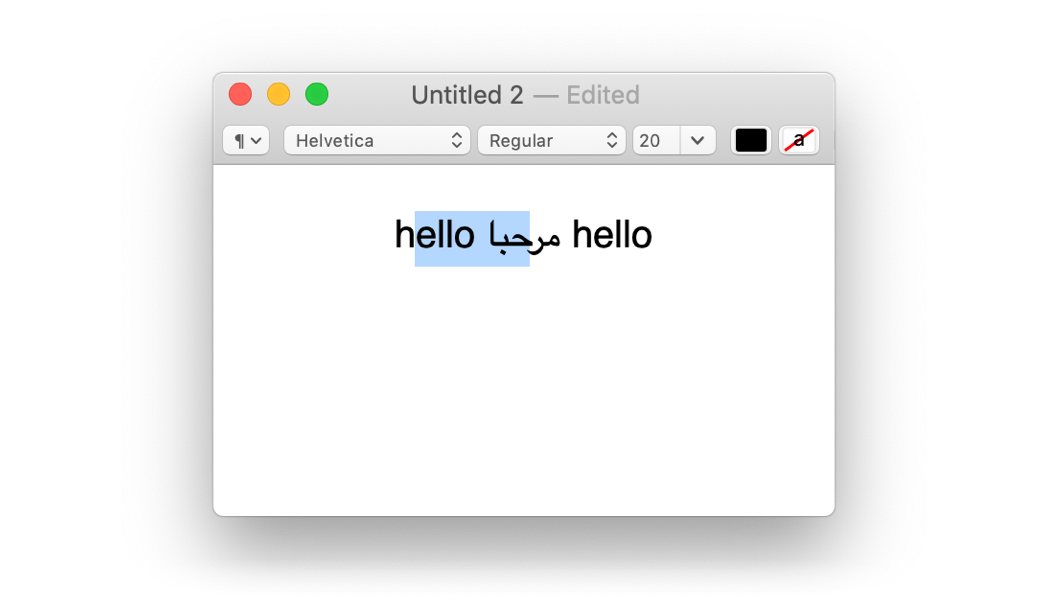

Alexis mentions disconnected selections in mixed bi-directional text, like this example from TextEdit:

This actually makes sense, since Arabic in strings is encoded from right to left, so this selection appears disconnected, but byte-wise represents a contiguous range of the string.

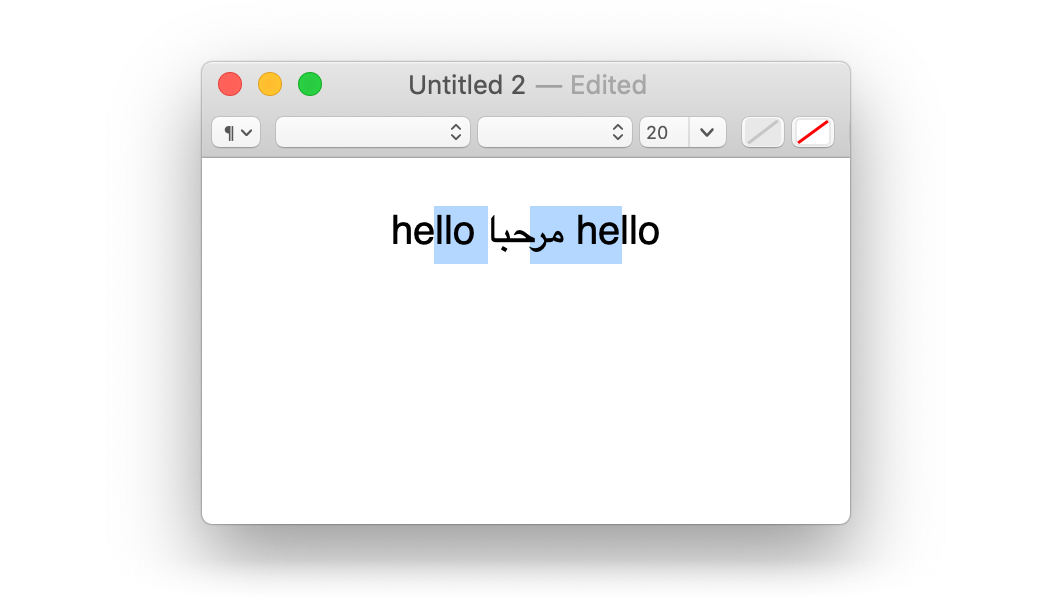

This makes it a little surprising, then, that we can get this selection:

Yes, that is a visually contiguous, byte-wise disconnected selection. Yes, this is bad. Some text editing engines do this when you select with the arrow keys instead of the mouse. The alternative is flipping left/right arrow keys inside the RTL range, which is also bad. There are no good solutions here.

For extra credit, you can try to figure out what’s going on here:

I don’t want to talk about that selection.

Input Methods are a Thing

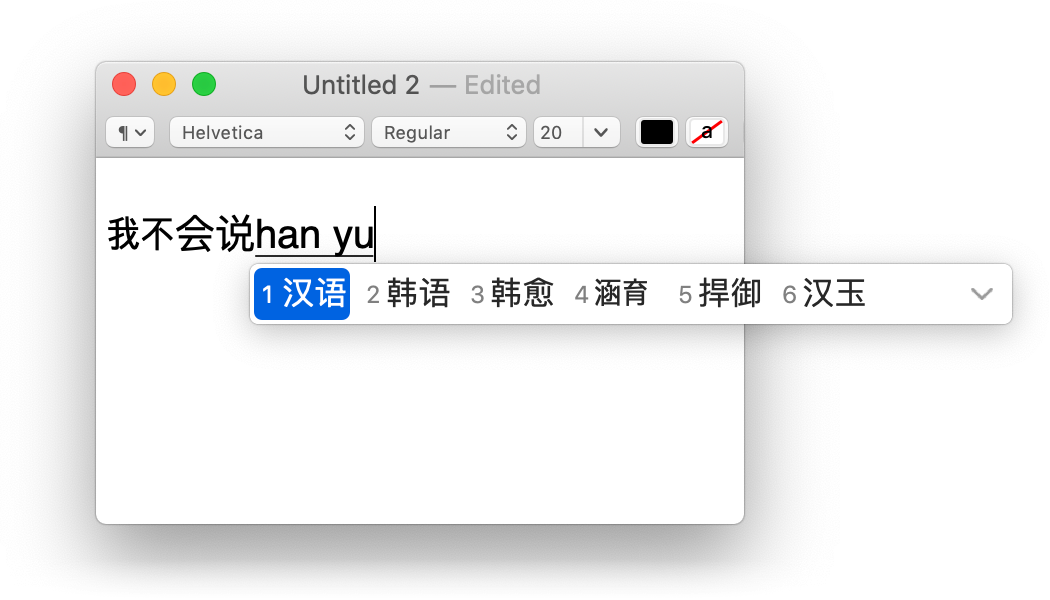

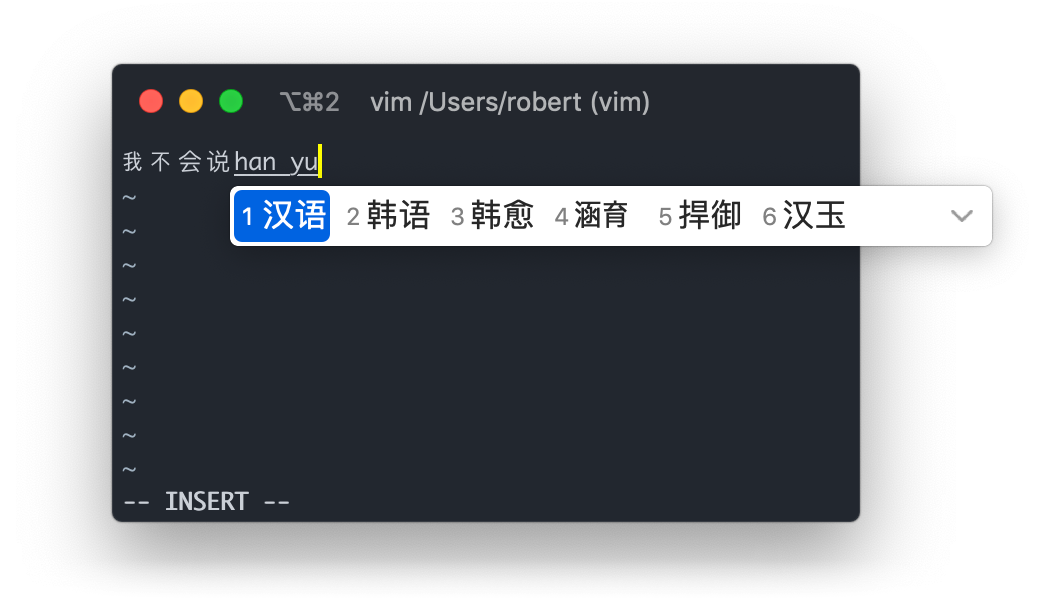

The software that translates keypresses into input is called an “input method” or “input method editor”. For the Latin alphabet used by English speakers, this isn’t terribly interesting software, since each keypress gets directly mapped to inserting a single character. But quite a few languages have too many characters for a single keyboard, and so they need to get creative. For instance, with some Chinese input methods, the user types the pronounciation of what they’re trying to say, and get a list of characters that match phonetically:

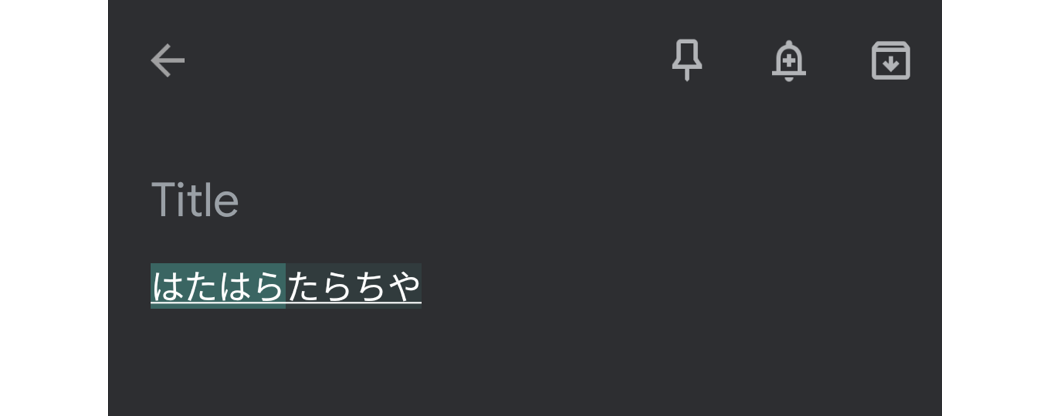

This is sometimes called a composing region, and it often appears as underlined text. Sometimes the input method needs to style this region. This Japanese input method on Android, for example, uses background color to create a split suggestion region:

Do all these various highlight and compose ranges interact with bidirectional text? Let’s not think about that.

Input methods have to work everywhere, even inside a terminal:

Nothing is actually sent to Vim until the Chinese character is selected from the list. You’re probably thinking “but how would that work with Vim’s command mode?” Not very well. This is why, on the web, text input and keypresses are separate events. Terminals conflate these two, causing problems.

You also may have noticed that the input method is a separate process from the application receiving text input, and since both the input method and application can make modifications to the state of the text field, we get concurrent editing problems. Windows solves this with its eight (8!) types of locks. Although holding a lock across process boundaries may sound questionable to you, most other platforms try to use imperfect heuristics to fix concurrency issues. Or they just hope race conditions don’t happen. In my experience, prayers are not a very effective concurrency primitive.

Why is this so complicated??

Jonathan Blow, in a talk about how software is getting worse, points to the example of Ken Thompson’s text editor, which Ken built in a single week. Plenty of the code in this blog post is accidental complexity. Does Windows need 128 interfaces and 8 kinds of locks to provide text input? Absolutely not. Are the bugs we’ve found in TextEdit disappointing, and a result of a complicated editing model? Yes. Are the wealth of bugs in modern programs something we should be worried about? I’m worried, at least.

But at the same time, Ken Thompson’s editor was much, much simpler than what we expect from our text editors today. Unicode supports almost every one of the ~7000 living languages used around the world, and plenty more dead languages too. These use a variety of scripts, directions, and input methods that each impose tricky (and in some cases, unsolved) problems on any editor we’d like to make. Our editor also needs to be usable by vision-impaired folks who use screen readers.

The necessary complexity here is immense. If anything, it’s a miracle of the simplicity of modern programming that we’re able to just slap down a <textarea> on a web page and instantly provide a text input for every internet user around the globe.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/32VrxrM

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.