Over the first half of the 1970s, the ecology of computer networking diversified from its original ARPANET ancestry along several dimensions. ARPANET users discovered a new application, electronic mail, which became the dominant activity on the network. Entrepreneurs spun-off their own ARPANET variants to serve commercial customers. And researchers from Hawaii to l’Hexagone developed new types of network to serve needs or rectify problems not addressed by ARPANET.

Almost everyone involved in this process abandoned the ARPANET’s original stated goal of allowing computing hardware and software to be shared among a diverse range of research sites, each with its own specialized resources. Computer networks became primarily a means for people to connect to one another, or to remote systems that acted as sources or sinks for human-readable information, i.e. information databases and printers.

This was a possibility foreseen by Licklider and Robert Taylor, though not what they had intended when they launched their first network experiments. Their 1968 article,”The Computer as a Communication Device” lacks the verve and timeless quality of visionary landmarks in the history of computing such as Vannevar Bush’s “As We May Think” or Turing’s “Computing Machinery and Intelligence.” Nonetheless, it provides a rather prescient glimpse of a social fabric woven together by computer systems. Licklider and Taylor described a not-to-distant future in which1

You will not send a letter or a telegram; you will simply identify the people whose files should be linked to yours and the parts to which they should be linked-and perhaps specify a coefficient of urgency. You will seldom make a telephone call; you will ask the network to link your consoles together.

…Available within the network will be functions and services to which you

subscribe on a regular basis and others that you call for when you need them.

In the former group will be investment guidance, tax counseling, selective

dissemination of information in your field of specialization, announcement of

cultural, sport, and entertainment events that fit your interests, etc.

The first and most important component of this computer-mediated future – electronic mail – spread like a virus across ARPANET in the 1970s, on its way to taking over the world.

To understand how electronic mail developed on ARPANET, you need to first understand an important change that overtook the network’s computer systems in the early 1970s. When ARPANET was first conceived in the mid-1960s, there was almost no commonality among the hardware and operating software running at each ARPA site. Many sites centered on custom, one-off research systems, such Multics at MIT, the TX-2 at Lincoln Labs, and the ILLIAC IV, under construction at the University of Illinois.

By 1973, on the other hand, the landscape of computer systems connected to the network had acquired a great deal of uniformity, thanks to the wild success of Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) in penetrating the academic computing market.2 DEC designed the PDP-10, released in 1968, to provide a rock-solid time-sharing experience for a small organization, with an array of tools and programming languages built-in to aid in customization. This was exactly what academic computing centers and research labs were looking for at the time.

BBN, the company responsible for overseeing the ARPANET, then made the package even more attractive by creating the Tenex operating system, which added paged virtual memory to the PDP-10. This greatly simplified the management and use of the system, by making it less important to exactly match the set of running programs to the available memory space. BBN supplied the Tenex software free-of-charge to other ARPA sites, and it soon became the dominant operating system on the network.

But what does all of this have to do with email? Electronic messaging was already familiar to users of time-sharing systems, most of which offered some kind of mailbox program by the late 1960s. They provided a form of digital inter-office mail; their reach extended only to other users of the same computer system. The first person to take advantage of the network to transfer mail from one machine to another was Ray Tomlinson, a BBN engineer and one of the authors of the Tenex software. He had already written a SNDMSG program for sending mail to other users on a single Tenex system, and a CPYNET program for sending files across the network. It required only a leap of imagination for him to see that he could combine the two to create a networked mail program. Previous mail programs had only required a user name to indicate the recipient, so Tomlinson came up with the idea of combining that local user name and the (local or remote) host name with an @ symbol3, to create an email address that was unique across the entire network.

Tomlinson began testing his new program locally in 1971, and in 1972 his networked version of SNDMSG was bundled into the Tenex release, allowing Tenex mail to break the bonds of a single site and spread across the network. The plurality of machines running Tenex made Tomlinson’s hybrid program available instantly to a large proportion of ARPANET users, and it became an immediate success. It did not take long for ARPA’s leaders to integrate email into the core of their working life. Stephen Lukasik, director of ARPA, was an early adopter, as was Larry Roberts, still head of the agency’s computer science office. The habit inevitably spread to their subordinates, and soon email became a basic fact of life of the culture of ARPANET.

Tomlinson’s mail software spawned a variety of imitations and elaborations from other users looking to improve on its rudimentary functionality. Most of the early innovation focused on the defects of the mail reading program. As email spread beyond a single computer, the volume of mail received by heavy users scaled with the size of the network, and the traditional approach of treating the mailbox as a raw text file was no longer effective. Larry Roberts himself, unable to deal effectively with the deluge of incoming messages, wrote his own software to manage his inbox called RD. By the mid-1970s, however, the most popular program by far was MSG, written by John Vittal of USC. We take for granted the ability to press a single button to fill out the title and recipient of outgoing message based on an incoming one. But it was Vittal’s MSG that first provided this killer “answer” feature in 1975; and it, too, was a Tenex program.

The diversity of efforts led to a need for standards. This marked the first, but far from the last, time that the computer networking community would have to develop ex post facto standards. Unlike the basic protocols for ARPANET, a variety of email practices already existed in the wild prior to any standard setting. The inevitable result was controversy and political struggle, centering around the main email standard documents, RFC 680 and 720. In particular, non-Tenex users expressed a certain prickly resentment about the Tenex-centric assumptions built into the proposals. The conflict never grew terribly hot – everyone on ARPANET in the 1970s was still part of the same, relatively small, academic community and the differences to be reconciled were not large. But it provided a taste of larger struggles to come.

The sudden success of email represented the most important development of the 1970s in the application layer of the network, the level most abstracted from the physical details of the network’s layout. At the same time, however, others had set out to redifine the foundational “link” layer, where bits flowed from machine to machine.

ALOHA

In 1968, Norman Abramson arrived at the University of Hawaii from California to serve a combined appointment as electrical engineering and computer science professor. The University he joined consisted of a main campus in Oahu as well as a secondary Hilo campus, and several other community colleges and research sites spread across Oahu, Kauai, Maui, and Hawaii. In between lay hundreds of miles of water and mountainous terrain. A brawny IBM 360/65 powered computer operations at the main campus, but ordering up an AT&T dedicated line to link a terminal to it from one of the community colleges was not so simple a matter as on the mainland.

Abramson was an expert in radar systems and information theory who did a stint as an engineer for Hughes Aircraft in Los Angeles. This new environment, with all the physical challenges it presented to wireline communications, seems to have inspired Abramson to a new idea – what if radio were actually a better way of connecting computers than the phone system, which after all was designed with the needs of voice, not data, in mind?

Abramson secured funding from Bob Taylor at ARPA to test this idea, with a system he called ALOHAnet. In its initial incarnation, it was not a computer network at all, but rather a medium for connecting remote terminals to a single time-sharing system, designed for the IBM machine at the Oahu campus. Like ARPANET, it had a dedicated minicomputer for processing packets sent and received by the 360/65 – Menehune, the Hawaiian equivalent of the IMP. ALOHAnet, however, dealt away with all the intermediate point-to-point routing used by ARPANET to get packets from one place to another. Instead any terminal wishing to send a message simply broadcast it into the ether in the allotted transmission frequency.

The traditional way for a radio engineer to handle a shared transmission band like this would have been to carve it up into time or frequency-based slots, and assign each terminal to its own slot. But to handle hundreds of terminals in such a scheme would mean limiting each to a small fraction of the available bandwidth, even though only a few might be in active use at any given moment. Instead, Abramson decided to do nothing to prevent more than one terminal from sending at the same time. If two or more messages overlapped they would become garbled, but the central computer would detect this via error-correcting codes, and would not acknowledge those packets. Failing to receive their acknowledgement, the sender(s) would try again after some random interval. Abramson calculated that this simple protocol could sustain up to a few hundred simultaneously active terminals, whose numerous collisions would still leave about 15% of the usable bandwidth. Beyond that, though, his calculations showed that the whole thing would collapse into a chaos of noise.

The Office Of The Future

Abramson’s “packet broadcasting” concept did not make a huge splash, at first. But it found new life a few years later, back on the mainland. The context was Xerox’s new Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), opened in 1970 just across from Stanford University, in a region recently dubbed “Silicon Valley.” Some of Xerox’s core xerography patents stood on the verge of expiration, and the company risked being trapped by its own success, unable or unwilling to adapt to the rise of computing and integrated circuits. Jack Goldman, head of research for Xerox, had convinced the bigwigs back East that a new lab – distanced from the influence of HQ, nestled in an attractive climate, and with premium salaries on offer – would attract the talent needed to keep Xerox’s edge, by designing the information architecture of the future.

PARC certainly succeeded in attracting top computer science talent, due not only to the environment and the generous pay, but also the presence of Robert Taylor, who had set the ARPANET into motion as head of ARPA’s Information Processing Technology Office in 1966. Robert Metcalfe, a prickly and ambitious young engineer and computer scientist from Brooklyn, was one of many wooed to PARC via an ARPA connection. He joined the lab in June 1972 after working part-time for ARPA a a Harvard graduate student, building the interface to connect MIT to the network. Even after joining PARC, he continued to work as an ARPANET ‘facilitator’, traveling around the country to help new sites get started on the network, and on the preparations for ARPA’s coming out party at the 1972 International Conference on Computer Communications.

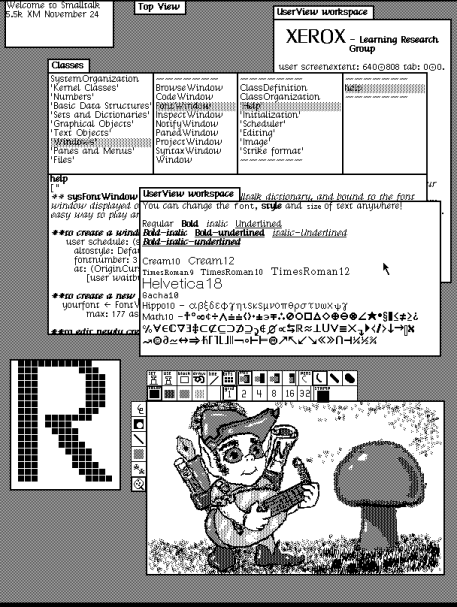

Among the projects percolating at PARC when Metcalfe arrived was a plan by Taylor to link dozens, or even hundreds, of small computers via a local network. Year after year, computers continued to decrease in price and size, as if bending to the indomitable will of Gordon Moore. The forward-looking engineers at PARC foresaw a not-far-distant future when every office worker would have his own computer. To that end, they designed and built a personal computer called Alto, a copy of which would be supplied to every researcher in the lab. Taylor, who had only become more convinced of the value of networking over the previous half-decade, also wanted these computers to be interconnected.

On arriving at PARC, Metcalfe took over the task of connecting up the lab’s PDP-10 clone to ARPANET, and quickly acquired a reputation as the “networking guy”. Therefore when Taylor asked for an Alto network, his peers turned to Metcalfe. Much like the computers on ARPANET, the Altos at PARC didn’t have much to say to one another. The compelling application for the network, once again, was in enabling human communication – in this case in the form of word and images printed by laser.

The core idea behind the laser printer did not originate at PARC, but back East, at the original Xerox research lab in Webster, New York. There a physicist named Gary Starkweather proved that the coherent beam of a laser could be used to deactivate the electrical charge of a xerographic drum, just like the diffuse light used in photocopying up to that point. Properly modulated, the beam could paint a image of arbitrary detail onto the drum, and thus onto paper (since only the uncharged areas of the drum picked up toner). Controlled by a computer, such a machine could produce any combination of images and text that a person might conceive, rather than merely reproducing existing documents like the photocopier. Starkweather received no support for these wild ideas from his colleagues or management in Webster, however, so he got himself transferred to PARC in 1971, where he found a far more receptive audience. The laser printer’s ability to render arbitrary images dot-by-dot provided the perfect mate for the Alto workstation, with its bit-mapped monochrome graphics. With a laser printer, the half-million pixels on a user’s display could be directly rendered onto paper with perfect fidelity.

Within about a year Starkweather, with the help of several other PARC engineers, had overcome the main technical challenges and built a working prototype of a laser printer, based on the chassis of the workhorse Xerox 7000 printer. It produced pages at the same rate – one per second – at 500 dots per linear inch. A character generator attached the printer crafted text from pre-defined fonts. Free-form imagery (other than what could be generated with custom fonts) was not yet supported, so the network did not need to carry the full 25 million bits-per-second or so required to feed the laser; nonetheless, a tremendous of amount of bandwidth would be needed to keep the printer busy at a time when the 50,000 bits-per-second ARPANET represented the state-of-the-art.

The Alto Aloha Network

How would Metcalfe bridge this huge gap in speed? Finally, we come back to ALOHAnet, for it turns out that Metcalfe knew packet broadcasting better than anyone. The previous summer, while staying in Washington with Steve Crocker on ARPA business, Metcalfe had pulled down volume of the proceedings of the Fall Joint Computer Conference, and came across Abramson’s ALOHAnet paper. He immediately realized that the basic idea was brilliant, but the implementation under-baked. With a few tweaks in the algorithm and assumptions – notably having senders listen for a clear channel before trying to broadcast, and exponentially increasing the re-transmission interval in response to congestion – he could achieve a bandwidth utilization of 90%, rather than the 15% calculated by Abramason. Metcalfe took a short leave from PARC to visit Hawaii, where he integrated his ideas about ALOHAnet into a revised version of his PhD thesis, after Harvard had rejected the original due to a lack of theoretical grounding.

Metcalfe originally called his plan to bring packet broadcasting to PARC the “ALTO ALOHA network”. Then, in a memo in May 1973, he rechristened it as Ether Net, invoking the luminiferous ether which nineteenth-century physicists had suposed to carry all electromagnetic radiation. “This will keep things general,” he wrote, “and who knows what other media will prove better than cable for a broadcast network; maybe radio or telephone circuits, or power wiring or frequency-multi-plexed CATV, or microwave environments, or even combinations thereof.”

Starting in June 1973, Metcalfe worked with another PARC engineer, David Boggs, to turn his theoretical concepts for a new high-speed network into a working system. Rather than sending signals over the air like ALOHA, they would bind the radio spectrum within the confines of a coaxial cable, greatly increasing the available bandwidth from the limited radio band allocated to the Menehune. The transmission medium itself was entirely passive, requiring no switching equipment at all for routing messages. It was cheap and easy to connect it hundreds of workstations – PARC engineers just ran coax cable through the building and added taps as needed – and it could handle three million bits per second.

By the fall of 1974, the complete prototype of the office of the future was up and running in Palo Alto, California – the initial batch of thirty altos with drawing, email, and word processing software, Starkweather’s prototype printer, and Ethernet to connect it all together. A central file server for storing data too large for the Alto’s local disk provided the only other shared resource. PARC originally offered the Ethernet controller as an optional accessory on the Alto, but once the system went live it became clear that it was essential, as the coax coursed with a steady flow of messages, many of them emerging from the printer as technical reports, memos, or academic papers.

Simultaneously with the development of the Alto, another PARC project attempted to carry the resource-sharing vision forward in a new direction. The PARC On Line Office System (POLOS), designed and implemented by Bill English and other refugees from Doug Engelbart’s oN-Line System (NLS) project at Stanford Research Institute, consisted of a network of Data General Nova minicomputers. Rather than dedicating each machine to a particular user’s needs, however, POLOS would shuttle work around among them, in order to serve the needs of the system as a whole as efficiently as possible. One machine might be rendering displays for several users, while another handled ARPANET traffic, and yet another ran word processing software. The complexity and coordination overhead of this approach proved unmanageable, and the scheme collapsed under its own weight.

Meanwhile, nothing more clearly showed Taylor’s emphatic rejection of the resource-sharing approach to networking than his embrace of the Alto. Alan Kay, Butler Lampson, and the other minds behind the Alto had brought all the computational power a user might need onto an independent computer at their desk, intended to be shared with no one. The function of the network was not to provide access to a heterogeneous set of computer resources, but to carry messages among these islands, each entire of itself, or perhaps to deposit them on some distant shore – for printing or long-term storage.

While both email and ALOHA developed under the umbrella of ARPA, the emergence of Ethernet was one of several signs in the first half of the 1970s that computer networking had become something too large and diverse for a single organization to dominate, a trend that we’ll continue to follow next time.

Further Reading

Michael Hiltzik, Dealers of Lightning (1999)

James Pelty, The History of Computer Communications, 1968-1988 (2007) [https://ift.tt/1ALMzVD]

M. Mitchell Waldrop, The Dream Machine (2001)

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/328OEPi

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.