We’ve filed a lawsuit challenging Stable Diffusion, a 21st-century collage tool that violates the rights of artists.

Because AI needs to be fair & ethical for everyone.

January 13, 2023

Hello. This is Matthew Butterick. I’m a writer, designer, programmer, and lawyer. In November 2022, I teamed up with the amazingly excellent class-action litigators Joseph Saveri, Cadio Zirpoli, and Travis Manfredi at the Joseph Saveri Law Firm to file a lawsuit against GitHub Copilot for its “unprecedented open-source software piracy”. (That lawsuit is still in progress.)

Since then, we’ve heard from people all over the world—especially writers, artists, programmers, and other creators—who are concerned about AI systems being trained on vast amounts of copyrighted work with no consent, no credit, and no compensation.

Today, we’re taking another step toward making AI fair & ethical for everyone. On behalf of three wonderful artist plaintiffs—Sarah Andersen, Kelly McKernan, and Karla Ortiz—we’ve filed a class-action lawsuit against Stability AI, DeviantArt, and Midjourney for their use of Stable Diffusion, a 21st-century collage tool that remixes the copyrighted works of millions of artists whose work was used as training data.

Joining as co-counsel are the terrific litigators Brian Clark and Laura Matson of Lockridge Grindal Nauen P.L.L.P.

Today’s filings:

As a lawyer who is also a longtime member of the visual-arts community, it’s an honor to stand up on behalf of fellow artists and continue this vital conversation about how AI will coexist with human culture and creativity.

The image-generator companies have made their views clear.

Now they can hear from artists.

Stable Diffusion is an artificial intelligence (AI) software product, released in August 2022 by a company called Stability AI.

Stable Diffusion contains unauthorized copies of millions—and possibly billions—of copyrighted images. These copies were made without the knowledge or consent of the artists.

Even assuming nominal damages of $1 per image, the value of this misappropriation would be roughly $5 billion. (For comparison, the largest art heist ever was the 1990 theft of 13 artworks from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, with a current estimated value of $500 million.)

Stable Diffusion belongs to a category of AI systems called generative AI. These systems are trained on a certain kind of creative work—for instance text, software code, or images—and then remix these works to derive (or “generate”) more works of the same kind.

Having copied the five billion images—without the consent of the original artists—Stable Diffusion relies on a mathematical process called diffusion to store compressed copies of these training images, which in turn are recombined to derive other images. It is, in short, a 21st-century collage tool.

These resulting images may or may not outwardly resemble the training images. Nevertheless, they are derived from copies of the training images, and compete with them in the marketplace. At minimum, Stable Diffusion’s ability to flood the market with an essentially unlimited number of infringing images will inflict permanent damage on the market for art and artists.

Even Stability AI CEO Emad Mostaque has forecast that “[f]uture [AI] models will be fully licensed”. But Stable Diffusion is not. It is a parasite that, if allowed to proliferate, will make artists extinct.

The diffusion technique was invented in 2015 by AI researchers at Stanford University. The diagram below, taken from the Stanford team’s research, illustrates the two phases of the diffusion process using a spiral as the example training image.

The first phase in diffusion is to take an image and progressively add more visual noise to it in a series of steps. (This process is depicted in the top row of the diagram.) At each step, the AI records how the addition of noise changes the image. By the last step, the image has been “diffused” into essentially random noise.

The second phase is like the first, but in reverse. (This process is depicted in the bottom row of the diagram, which reads right to left.) Having recorded the steps that turn a certain image into noise, the AI can run those steps backwards. Starting with some random noise, the AI applies the steps in reverse. By removing noise (or “denoising”) the data, the AI will emit a copy of the original image.

In the diagram, the reconstructed spiral (in red) has some fuzzy parts in the lower half that the original spiral (in blue) does not. Though the red spiral is plainly a copy of the blue spiral, in computer terms it would be called a lossy copy, meaning some details are lost in translation. This is true of numerous digital data formats, including MP3 and JPEG, that also make highly compressed copies of digital data by omitting small details.

In short, diffusion is a way for an AI program to figure out how to reconstruct a copy of the training data through denoising. Because this is so, in copyright terms it’s no different from an MP3 or JPEG—a way of storing a compressed copy of certain digital data.

In 2020, the diffusion technique was improved by researchers at UC Berkeley in two ways:

-

They showed how a diffusion model could store its training images in a more compressed format without impacting its ability to reconstruct high-fidelity copies. These compressed copies of training images are known as latent images.

-

They found that these latent images could be interpolated—meaning, blended mathematically—to produce new derivative images.

The diagram below, taken from the Berkeley team’s research, shows how this process works.

The image in the red frame has been interpolated from the two “Source” images pixel by pixel. It looks like two translucent face images stacked on top of each other, not a single convincing face.

The image in the green frame has been generated differently. In that case, the two source images have been compressed into latent images. Once these latent images have been interpolated, this newly interpolated latent image has been reconstructed into pixels using the denoising process. Compared to the pixel-by-pixel interpolation, the advantage is apparent: the interpolation based on latent images looks like a single convincing human face, not an overlay of two faces.

Despite the difference in results, in copyright terms, these two modes of interpolation are equivalent: they both generate derivative works by interpolating two source images.

In 2022, the diffusion technique was further improved by researchers in Munich. These researchers figured out how to shape the denoising process with extra information. This process is called conditioning. (One of these researchers, Robin Rombach, is now employed by Stability AI as a developer of Stable Diffusion.)

The most common tool for conditioning is short text descriptions, also known as text prompts, that describe elements of the image, e.g.—“a dog wearing a baseball cap while eating ice cream”. (Result shown at right.) This gave rise to the dominant interface of Stable Diffusion and other AI image generators: converting a text prompt into an image.

The text-prompt interface serves another purpose, however. It creates a layer of magical misdirection that makes it harder for users to coax out obvious copies of the training images (though not impossible). Nevertheless, because all the visual information in the system is derived from the copyrighted training images, the images emitted—regardless of outward appearance—are necessarily works derived from those training images.

Stability AI, founded by Emad Mostaque, is based in London.

Stability AI funded LAION, a German organization that is creating ever-larger image datasets—without consent, credit, or compensation to the original artists—for use by AI companies.

Stability AI is the developer of Stable Diffusion. Stability AI trained Stable Diffusion using the LAION dataset.

Stability AI also released DreamStudio, a paid app that packages Stable Diffusion in a web interface.

DeviantArt was founded in 2000 and has long been one of the largest artist communities on the web.

As shown by Simon Willison and Andy Baio, thousands—and probably closer to millions—of images in LAION were copied from DeviantArt and used to train Stable Diffusion.

Rather than stand up for its community of artists by protecting them against AI training, DeviantArt instead chose to release DreamUp, a paid app built around Stable Diffusion. In turn, a flood of AI-generated art has inundated DeviantArt, crowding out human artists.

When confronted about the ethics and legality of these maneuvers during a live Q&A session in November 2022, members of the DeviantArt management team, including CEO Moti Levy, could not explain why they betrayed their artist community by embracing Stable Diffusion, while intentionally violating their own terms of service and privacy policy.

Midjourney was founded in 2021 by David Holz in San Francisco. Midjourney offers a text-to-image generator through Discord and a web app.

Though holding itself out as a “research lab”, Midjourney has cultivated a large audience of paying customers who use Midjourney’s image generator professionally. Holz has said he wants Midjourney to be “focused toward making everything beautiful and artistic looking.”

To that end, Holz has admitted that Midjourney is trained on “a big scrape of the internet”. Though when asked about the ethics of massive copying of training images, he said—

There are no laws specifically about that.

And when Holz was further asked about allowing artists to opt out of training, he said—

We’re looking at that. The challenge now is finding out what the rules are.

We look forward to helping Mr. Holz find out about the many state and federal laws that protect artists and their work.

Our plaintiffs are wonderful, accomplished artists who have stepped forward to represent a class of thousands—possibly millions—of fellow artists affected by generative AI.

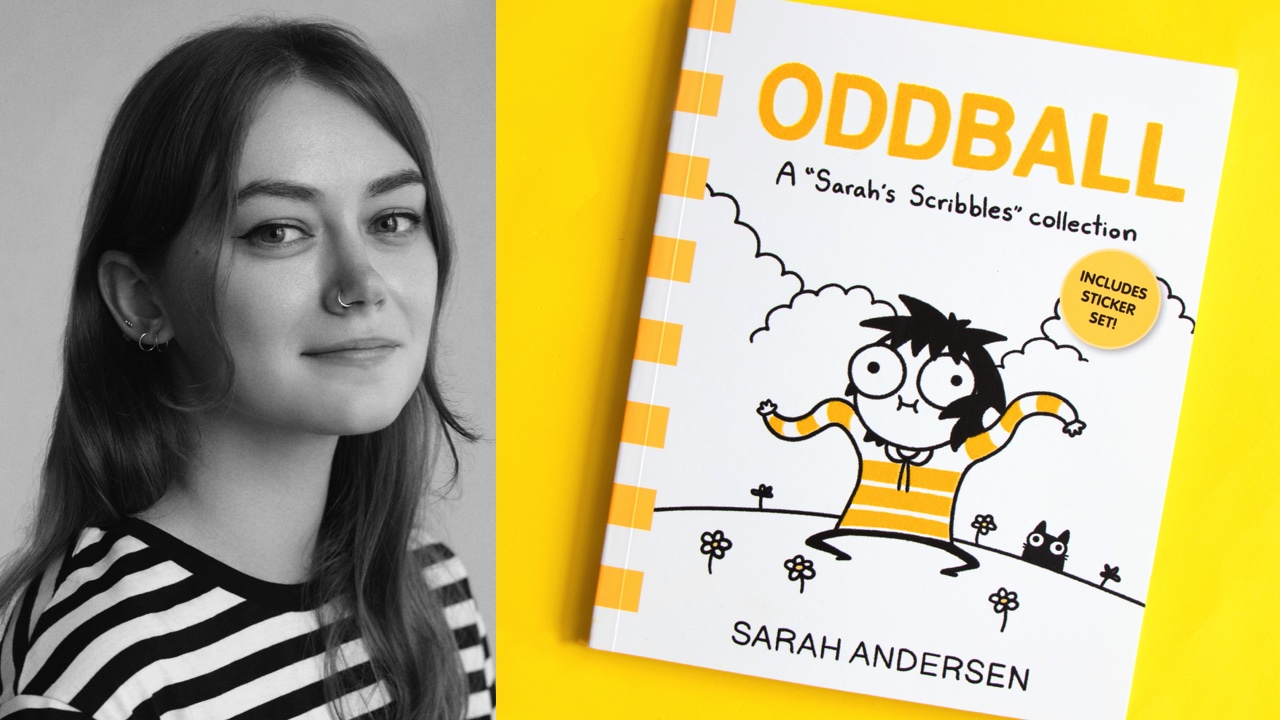

Sarah Andersen is a cartoonist and illustrator. She graduated from the Maryland Institute College of Art in 2014. She currently lives in Portland, Oregon. Her semi-autobiographical comic strip, Sarah’s Scribbles, finds the humor in living as an introvert. Her graphic novel FANGS was nominated for an Eisner Award.

Kelly McKernan is an independent artist based in Nashville. They graduated from Kennesaw State University in 2009 and have been a full-time artist since 2012. Kelly creates original watercolor and acryla gouache paintings for galleries, private commissions, and their online store. In addition to maintaining a large social-media following, Kelly shares tutorials and teaches workshops, travels across the US for events and comic-cons, and also creates illustrations for books, comics, games, and more.

Karla Ortiz is a Puerto Rican, internationally recognized, award-winning artist. With her exceptional design sense, realistic renders, and character-driven narratives, Karla has contributed to many big-budget projects in the film, television and video-game industries. Karla is also a regular illustrator for major publishing and role-playing game companies.

Karla’s figurative and mysterious art has been showcased in notable galleries such as Spoke Art and Hashimoto Contemporary in San Francisco; Nucleus Gallery, Thinkspace, and Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Los Angeles; and Galerie Arludik in Paris. She currently lives in San Francisco with her cat Bady.

If you’re a member of the press or the public with other questions about this case or related topics, contact stablediffusion_inquiries@saverilawfirm.com. (Though please don’t send confidential or privileged information.)

This web page is informational. General principles of law are discussed. But neither Matthew Butterick nor anyone at the Joseph Saveri Law Firm is your lawyer, and nothing here is offered as legal advice. References to copyright pertain to US law. This page will be updated as new information becomes available.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/jLN08yD

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.