I received a lot of support for my recent post on the folly of the University of California’s decision to drop the SAT, as well as a lot of pushback. I’ve done several podcasts in the past week on this question and will share them in this week’s Saturday evening roundup post. I recommend this resource for an exhaustive exploration of the SES-SAT question specifically. I want to take a little time and go through a few dynamics of this conversation that I think are important. I will say that I find this a particularly frustrating debate in large measure because many liberals loudly and confidently repeat “facts” that are in reality empirically indefensible half-truths or out-and-out errors and will not relent when this is brought to their attention. That’s no way to arrive at more equitable and fair college admissions.

Research has found again and again that considering GPA+SAT results in the most accurate predictions of college success.

This paper aggregates three of the most commonly-cited studies performed to answer the question of how best to quantitatively predict college performance. Again and again, we have found that SAT scores explain variance in college GPA and graduation rates not explained by GPA. In other words, they provide useful predictive information that can be utilized to reduce the number of students who are accepted into college who then fail out, a major negative event in a young person’s life due to opportunity cost and taking on student loan debt. The predictive effectiveness of the SAT is inconvenient for liberals who hate the test, but it is about as empirically well-justified as a claim about education can be, so they try to dissemble their way around it. The simple fact of the matter is that, for making the determinations that college admissions departments are meant to make, the SAT is a useful tool. Getting rid of it just makes us dumber.

How well do “holistic” factors predict college success? lol, nobody even pretends they can do that.

The variance attributable to SES is simply not that big.

In statistics we will often make reference to r², which is a metric that tells us how much of the variance in an output variable is explained by an input variable. (Here is a brief explainer.) The theoretical maximum bound for r² is 1.0, in a situation in which the input variable explains all of the variance. In the Sackett et al (2012) dataset that I referred to in my post, with an n of ~150,000 the r² for combined SAT scores and SES is .0625. In Zwick and Green (2007), with an n of ~99,000, the r² is .137 for the SAT Verbal and 0.128 for the SAT Math even when looking at the across-school correlations that result in stronger correlations between SAT and SES. That is, less than 14% of the variance in SAT scores can be explained by SES in two massive and representative samples. And yet liberal critics of the SAT constantly claim that the test “just measures income.” There are a lot of issues in education in which reasonable people can disagree about the interpretation of data. This is not one of them. There is nothing complex or controversial about this kind of analysis and it is simply dishonest to keep pushing the debunked claim here. Stop saying that the SAT is an income test. It is not.

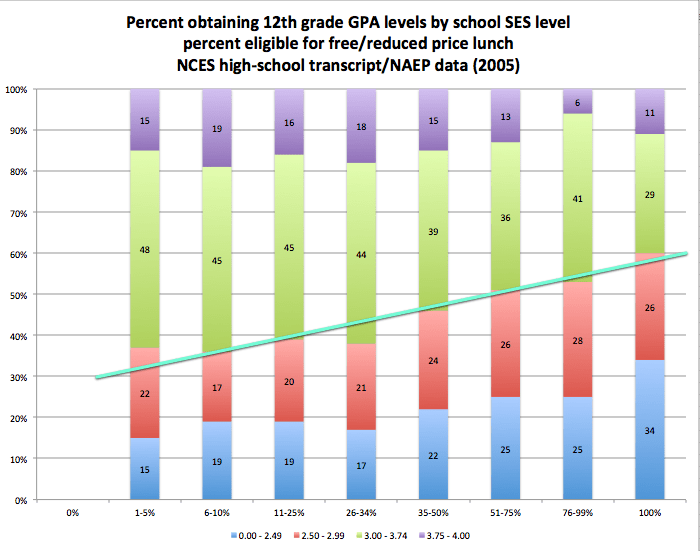

GPA is SES-stratified too.

One of the bizarre elements of this conversation is that critics of the SAT routinely argue for the social value of replacing GPA+SATs with GPA, and criticize the SES effect in SATs while doing so. But GPA is also SES-influenced as well!

In the Zwick and Green study cited above, GPA correlates with SES at .171 - smaller than the SAT correlation, but not much smaller. As with SATs, I would call this a real but ultimately small association. GPA-SES correlations jump around a lot more than SAT-SES correlations do depending on study (and this says not-great things about GPA as a predictor, incidentally) and I invite you to investigate other datasets. But there is no question that GPA is attenuated by SES, a fact SAT critics simply ignore.

This association is real even though GPAs are generally normed, systematically or not, to show a grade distribution through a given school population. That is, educators in specific contexts will tend to assign a distribution of scores throughout their classes even though their classes are non-randomly assembled and represent a skewed performance sample regardless of context. (This means, among other things, that high school GPA is a less objective and consistent predictor, which is precisely the problem the SAT is meant to solve; the SAT’s critics have literally no answer when you point out the inherent subjectivity of GPA to them.) This is why many or most colleges have algorithms that they use to adjust raw reported high school GPAs, which they know they can’t trust - schools will go to great lengths to unduly privilege their students in the college rat race. And there’s every reason to think that the adjustments colleges make to GPA likely deepen the influence of SES. So the criterion that many SAT critics would like to focus on exclusively to the detriment of the SAT replicates or even intensifies their claimed problem with the SAT. It makes no sense. I think people are not doing a lot of thinking here.

The only reason to use graphs or rather than quantitative correlational or regression data is to obscure reality.

A lot of this conversation involves people doing this:

But this is strange: we have statistical tools like Pearson coefficients and regression analyses precisely so that people don’t have to eyeball charts and try to estimate what we know how to represent with quantitative rigor. Yet people throw charts and graphs around in this debate constantly. This Washington Post piece, which I’ve had sent to me as some sort of devastating rejoinder a half-dozen times, asserts that “SAT scores are highly correlated with income” and then proceeds to… not report a correlation coefficient. Why would people do that? Because you can hide from the numerical precision of r² and similar metrics by doing so. The only reason to tweet a graph or chart at someone rather than to report a coefficient of determination is to obfuscate.

We know there are issues here because the SATs are quantitatively transparent.

How do we know that SAT has some correlation with SES? Because SAT scores are quantitative and can thus be quantitatively analyzed for issues of equity and fairness. The “holistic” criteria progressives cling to can’t be thus analyzed. This study, which shows that (whoops) college essays are more SES-influenced than the SATs are, is a noble effort, but it involves the kind of judgment calls about analysis that we’d prefer not to have to make, and this can’t be scaled up the way that you can simply regress a couple figures in a spreadsheet as much as you would like. The broader world of holistic factors is even worse in this regard, and this is precisely why colleges want to use those factors. With no quantitative accountability, colleges will be able to choose whoever they want - such as, I don’t know, wealthy students whose parents will make a lot of donations - and we’ll never know what they’re up to. Does that sound enlightened to you?

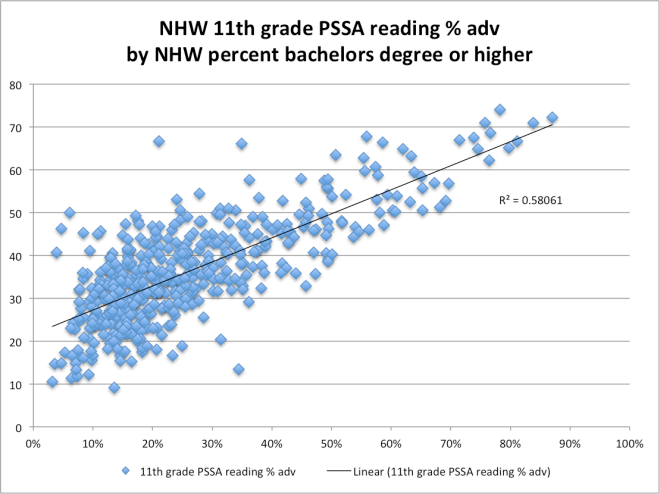

The perceived SES effect in SAT scores is a parental education effect.

From the same researcher as the resource shared at the top, here’s all you need to know. I’m sure some would rush to say “but having educated parents is an advantage the student can’t control too!” Yes, but it is also an advantage that pertains to grades as well, again directly undercutting the preference for a focus on GPA, and the fact that the advantage is in some sense unfair does not mean that it is not real. Children with well-educated parents having better academic outcomes is about as intuitive a finding as I can imagine even if we don’t posit a genetic influence on academic ability. And, as with SES, parent education level also shows up in state tests, IQ tests, the NAEP…. Part of the problem with this conversation is that people assume these correlations are evidence that the tests are faulty. But the SAT’s job is not to determine the legitimacy of the factors that are causing some students to be more college-ready than others. The test’s job is to predict which students will flourish when they get to college. The SAT does that job very well. People are just uncomfortable about the implications of what they predict.

The perceived SES effect is also a race effect.

Income differences don’t explain the race gaps in SAT data. (If you fear that this attitude is an artifact of white supremacy, you might ask if The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education would be peddling such a narrative.) But race explains most of the SES effect. When we talk about building a predictive model, we have an output variable that we’re interested in, here SAT scores, and we have predictors, including interval scale data like income and categorical data like race. As we put things into a model, we can determine what’s more predictive and what’s not. One common outcome is that adding one predictor removes the influence of another - that is, the new predictor better explains the variance previously attributed to the old predictor. (Overlapping sums of squares can be tricky to think through but I believe are essential to grasping multivariate models in frequentist statistics.) These models can be counterintuitive - the order that you put variables into your model matters, which is certainly a bit hard to grok. But what we find, when we consider race, parent’s education, and SES in SAT scores, is that the income effect disappears.

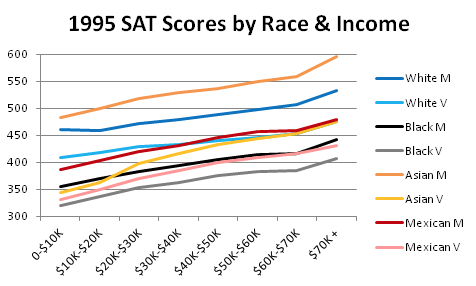

Income steps do, in a very coarse analysis, match SAT steps. And within each racial group, income steps do, again considered coarsely, match SAT steps. But across races this is not true, as can be seen in the graph above. The hierarchy of income in this country goes Asian>White>Hispanic>Black, and the hierarchy of SAT scores goes Asian>White>Hispanic>Black. But there is significantly more predictive power from looking at racial categories than from looking at income steps, which are generally a function of racial group, creating the impression of a stronger income effect than there actually is. In fact on the SAT Math, for example, Asian students from the bottom income quintile outperform Black students from the top income quintile.

Of course, all of this makes people uncomfortable.

Racial gaps in SAT data are perfectly predictable given antiracist beliefs.

It makes people uncomfortable because racial dynamics in education get at some really tense intersections between racist rhetoric and legitimate analysis. What I would like to remind everyone is that the perception of Black and Hispanic students lagging behind in educational metrics like the SAT is perfectly in keeping with the antiracist vision of the world. We are told that Black and Hispanic students face all manner of social and economic and cultural barriers. No doubt this is true - so we should not be at all surprised to find that educational outcomes are stratified along racial lines. The problem is that these inequalities don’t merely result in the appearance of lower preparedness for minority students. They result in the actuality of lower preparedness for minority students. Which means that the problem is not in college admissions, but in the inequalities themselves and the very real gap in academic skills they produce. As in so many cases liberals are trying to skip the hard part here.

The “cultural bias” argument is considered and invoked selectively.

It’s important to remember that the SAT was rewritten three times to try and address the supposed cultural biases of the test. You know how they got rid of the analogies? They did so because those were named as part of the “cultural bias” that was argued to be the source of Black and Hispanic struggles on the test. None of these rewrites closed these race gaps. Again, racial stratification exists in all educational metrics we have, from GPA to NAEP to state standardized tests to graduation rates, so the expectation that the SAT should be different is odd. But about that cultural bias: why would recent Asian immigrant students outperform white students, the second-highest performing racial category and due to their size the effective baseline, if the tests are so culturally biased? I’m supposed to understand that a first generation kid whose parents started their flight from Laos on a raft made from tires are the beneficiaries of the cultural biases of a bunch of ETS employees? A kid who came here from Chengdu when he was 10 and whose parents both work 80 hours a week at their restaurant in order to clear $30,000 in annual profits, he’s benefitting from cultural bias in his favor? It’s insulting. The racial disparities we see in education are complex and the discussion must be had carefully. But I find it very disheartening how progressives routinely dismiss the excellence achieved by Asian students from socioeconomically and ethnically marginalized backgrounds - precisely the type of excellence you would expect them to celebrate.

There is no reason to believe that getting rid of the SATs will increase what people actually mean by “diversity” at elite colleges, and every reason to believe colleges will continue to game these systems.

One of my great frustrations with this conversation is that it typically involves idealizing the college admissions process, which is in reality about the least idealistic process I can think of. This must be drilled into the heads of the liberals who think that eliminating the SAT is the key to getting more poor Black and Hispanic students into elite colleges: we have every reason to believe that colleges and universities are meeting their internal diversity goals by pursuing affluent first-generation and international Black and Hispanic students. Private colleges and universities jealously guard their internal admissions data, which is absurd for several reasons, the biggest of which is that we are handing them massive tax breaks in exchange for a complete lack of transparency in how they choose students. But both research and widespread industry perception tells us that, for many colleges, and particularly elite colleges, slots reserved for Black and Hispanic students are going to wealthy first generation children of affluent African and South American parents or to international students. (The latter are particularly attractive because international students are frequently ineligible for various types of financial aid and thus pay full freight in tuition, plus frequently onerous fees; when I was at Purdue, resident Indiana students paid about $8,000 a year and international undergraduate students paid better than $40,000 a year.)

Jay Caspian Kang summarized the reality in this essential piece on the place of Asian American students in the broader affirmative action context:

… the spirit of affirmative action has been replaced by a largely cosmetic, overly simplified diversity that allows elite institutions to report gains in black and Latino student populations without having to engage in the harder work of undoing systemic inequality. Waters’s question from 2004 has largely gone unaddressed: If you stop random supporters of affirmative action on the street and ask why they believe in it, they will most likely discuss the need to address the harms of historic, institutional racism. They may talk abstractly about a poor, “inner city” or “urban” kid in, say, Detroit and how his test scores, grades and accomplishments should be evaluated in the context of the extraordinary inequality within this country.

The truth at Harvard and other elite private colleges is that the supposed zero-sum game of admissions slots isn’t really between Asian immigrants and the descendants of enslaved people, but rather between Asian immigrants, Latino immigrants and black immigrants. Some inevitable, deeply uncomfortable questions arise: If you compare an Asian-American student raised in poverty by parents who fled Vietnam during the fall of Saigon with the son of Chilean doctors who come from generational wealth and sent their child to 12 years of private school, who is more privileged?… At Harvard and other elite schools, the outlier example is the “inner city” kid from Detroit.

What’s the goal, here? If it’s to increase cardboard-cutout “diversity” by giving schools more leeway to recruit wealthy kids from Argentina and Nigeria, well, cool. It’ll probably work. But for the poor minority students, particularly the descendants of African slaves that most people think of when they think of affirmative action? No. Admissions departments at most colleges are revenue-generation units before they are anything else. While most elite schools would love to pick up a few more brilliant African American students from poor backgrounds, at scale they are not in the business of aggressively recruiting students who need a lot of financial aid and whose parents can’t make donations. They’re in the business of business. I’m sorry if this is injurious to the ideals of people in academia, but you should know this stuff better than I do.

Class-based affirmative action programs would probably result in more acceptances for American-born descendants of African slaves.

If you talk about class-based affirmative action as an alternative to race-based, many people will accuse you of not “centering” race, of failing to take white supremacy seriously, of being a class reductionist…. The irony is that, because of the income dynamics of the United States and the tendency of colleges to use diversity slots to merely choose a different kind of affluent student, class-based affirmative action would probably do more to help the kinds of kids that people think they’re helping when they advocate for diversity programs. Of course, there’s no reason we couldn’t insist on class-and-race-conscious college admissions.

Throwing underprepared students into the deep end is unjust too.

Black college students drop out of college at a rate 22 points higher than white. Again, all of the data (SAT, GPA, NAEP, state tests, graduation rate) is telling us that Black and Hispanic students really are less prepared than their white and Asian peers. Which means that if you’re just looking for ways to crank the spigot and send more of them to school, you’re going to be setting them up to take on student loan debt and then fail out, leaving them in the supremely unfortunate position of trying to pay off that debt without a degree that raises their earning potential. What bothers me most about the liberal attitude towards the SAT is that it’s so indifferent to the bigger picture. Hey, let’s just get rid of the test, and let more Black and Hispanic kids in! And then when those kids drop out at far higher rates, those liberals are nowhere to be found. That’s the opposite of real support.

The path, for me, is simple: race+class-based affirmative action combined with remediation and support. The University of Rhode Island’s Talent Development program is a good start: kids who wouldn’t ordinarily get into URI, most of them Black and Hispanic and almost-universally lower income, get acceptances, but they are on probation for their first several years, have to attend support programs the summers before freshman and sophomore year, and are required (not encouraged) to attend tutoring sessions and submit their work for regular checkups to ensure they’re getting the job done. This is what an actual program to help Black and Hispanic students look like. And the students perform significantly better than demographically-similar students, though still worse than other groups, as I understand it. Problem is, remediation is expensive, so the colleges would have to spend money and do a lot of work. It’s so much easier to just get kids who make the website look more diverse! Of course, in the broader sense, the ultimate support program is large-scale societal change of the type I advocate for in The Cult of Smart. We could do the hard work of addressing the actual systemic problems that college admissions reveal, instead of expecting college admissions to magically solve problems it can’t solve. We could choose to fix those big problems, and you can commit to that effort.

Or you can say “uh, excuse me, the SAT is just an income test!” and act like you’ve just made a devastatingly clever point. That seems to be the point for a lot of you.

In this conversation with C. Derrick Varn, a public school educator who is trained in educational research methods, I dive into some of the broader issues in what we know about education and how we talk about it.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/3p5cpE8

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.