By Douglas Hunter – Published May 23, 2013

On June 19, 1606, John Knight ran out of options.

Several days of jousting with contrary winds, waves and shifting ice floes in the Labrador Sea in his little ship, the Hopewell, had forced him onto the Labrador shore, somewhere north of present-day Nain. Anchored in an uncharted bay, the Hopewell was soon battered by ice. The hull was holed, the rudder unshipped. Only by settling on the bottom, her hold filling with water, did the Hopewell not actually sink altogether.

The single-ship Hopewell expedition was the first English effort to investigate a possible Northwest Passage to Asia since George Waymouth’s Discovery voyage of 1602. Waymouth claimed to have sailed 100 leagues—some 300 nautical miles—beyond the tide-ripped entrance to a strait between northern Labrador and Baffin Island that John Davis in his 1587 voyage journal had described as “a mighty overfal, and roring, and with divers circular motions like whirlepooles, in such sort as forcible streames passe thorow the arches of bridges.” This entrance became known as the Furious Overfall. Knight had fallen short of gaining it by about 250 nautical miles, and was in danger of losing both ship and crew.

On June 25 Knight sent a party out in the ship’s boat under command of his mate, Edward Gorrell, to see if there was a safer anchorage at an island about a mile away, where he could move the Hopewell for further repairs—provided he could first refloat her. But the ice was so thick that Gorrell could make no headway. The next morning, Knight wrote “Thursday the 26, beinge faire wether,” and that was all. He paused in the midst of writing and decided to investigate the nearby island himself. He assembled a party consisting of Gorrell, his own brother Gabriel, and three other men. In addition to navigational instruments, Knight took along an arsenal of weapons: four pistols, three muskets, five swords and two half pikes.

The ice pack had eased enough to allow Knight’s party to reach the island at ten o’clock in the morning. He ordered a trumpeter and another crewmember named Oliver Browne to remain with the boat while he led the rest on a reconnaissance.

Knight and his companions walked over the island’s rise and vanished without a sound.

I. Boatman of the Underworld

Northern European mariners were determined to prove a route to the riches of eastern Asia that was shorter than the proven one around Africa, and the history of their search for a northern passage to Asia is full of disappearances. The vanishing of John Knight and his three companions is one of the less celebrated, overshadowed by the destruction of the Franklin expedition’s Erebus and Terror and their entire crews in the late 1840s.

Yet Knight’s loss remains compelling as part of a chain of disappearances and appearances. Some northern passage seekers seemed to disappear and yet somehow did not, their lives refloating, like the Hopewell, to sail again.

The best explanation for the disappearance of John Knight’s party was that they were surprised by a group of Inuit, who abducted or killed them before the Englishmen could fire a single volley. Soon after Knight failed to return to the ship’s boat, the Hopewell was attacked by a group of “very little people, tawnie coloured, thin or no bear[d]s, and flat nosed,” that was repelled with musket fire. The ten remaining crewmembers managed to refloat the ship and limp to a fishing station at Fogo Bay in Newfoundland, where the Hopewell was rendered sufficiently shipshape to return to England. There, the Hopewell was placed in the hands of a new name in polar passage-seeking: Henry Hudson.

Nothing is known about Hudson’s nautical career before that moment. He effectively stepped into the historical record when John Knight took his leave of it, and he used Knight’s Hopewell on two northern voyages. The first, in 1607, attempted and failed to scout a route to Asia directly over the North Pole. The second, in 1608, attempted and failed to prove a route to Asia by the Northeast Passage, over the top of Russia. On a quixotic third voyage in the employ of the Dutch East India Company, Hudson defied his sailing instructions. After again failing to prove the Northeast Passage, the task for which he had been hired, he took the ship all the way to eastern North America, where he became the first European known to have explored the river that now bears his name.

For his fourth voyage, Hudson was back in the employ of English interests, and they gave him the Discovery, which was most likely the same Discovery used by George Waymouth in 1602. They sent him back to complete the task that John Knight could not, resuming Waymouth’s investigations beyond the Furious Overfall. He was even given Waymouth’s mate, William Cobreth. Hudson ditched him before clearing the Thames and replaced him with a favourite, Robert Juet. That set the stage for Hudson’s own vanishing, cast away in a ship’s boat in James Bay with his son and seven other luckless men by mutineers—whose ringleaders included Juet—in June 1611.

Long before Hudson was dispatched to his unknowable fate, the Hopewell, then Knight’s ship, lay dashed on the Labrador shore in 1606. The pen that John Knight had set down after writing the word weather was next taken up by Oliver Browne, one of the two men he had left behind in the ship’s boat as he and his companions marched over the island’s rise into whatever otherness consumed them. Browne completed the account of the voyage and answered to the investors when the Hopewell finally regained England. There was good reason to suspect that Knight might have been abandoned by a crew who were tired of the fearful struggle to reach the Furious Overfall and only wanted to go home.

The truth as to Knight’s disappearance is a mystery that haunts any researcher—but his immediate successor’s identity is just as puzzling. I could learn nothing about Oliver Browne’s existence, before or after that voyage, as I researched my book God’s Mercies. But I was nagged by the fact that, as Clements R. Markham noted of Samuel Purchas’s account of the Knight expedition in Purchas His Pilgrimes (1625), “There is a mark like the beginning of an l, followed by the e in Browne…” Purchas’s rendering of his name as something like Brownle was terribly close to Oliver Brownel, which was how the English rendered the name Olivier Brunel, a Fleming who made several attempts to prove the Northeast Passage route to Asia. Word was that Brunel had drowned in 1585 on the coast of northern Russia when his ship’s boat capsized. That may well have been the case. But who was this Oliver Browne, who had left Knight behind on that island, never attempting to look for him, and had then guided the Hopewell home?

Was Oliver Browne in fact Oliver Brownel, who was in fact Olivier Brunel? If so, Brunel first would have made himself disappear, to avoid unhappy backers when his last voyage ended in failure and financial loss. He would have then placed himself and his rare expertise in high-latitude sailing at the service of English merchant adventurers, who assigned him to the Knight expedition. It thus became Brunel/Brownel/Browne’s misfortune (or opportunity) to usher John Knight and his companions out of existence.

There is yet another way to envision Oliver Browne: as a spectral figure, a boatman of the underworld. Brunel, who had drowned when his ship’s boat capsized, had emerged from his watery grave to row Knight to his own demise. He then linked Knight to Hudson via the resurrected Hopewell—a ship raised from a watery grave, just as Brunel was—before disappearing again. And Hudson, just like Knight, would go to an unknown grave.

II. Strangeness Visible

The history of Arctic exploration is full of cul de sacs, of narrow channels in ice fields, of straits that turn out to be bays, and of illusions that appeared to be opportunities. Some adventurers hesitated and missed breakthroughs of discovery. Others rushed in and found their retreats cut off by enclosing pack ice that ground their ships to flinders. Islands also appeared where none existed: cloudbanks and enormous ice fields masqueraded as solid ground. People saw things that were not there—or that we insist could never have been there.

Writing the history of Arctic exploration involves its own mirages. As historians, we mirror the anxieties of our subjects in where we choose to steer our own research. Possibilities tantalize, and one either pencils cautious question marks on the chart or follows them, hoping they lead somewhere. It can be a disorienting field in which to work, especially where the early voyages are concerned. Evidence is thin, and the smallest clues (a single name, a few words in a journal), can open grand vistas—or at least promise to do so.

Sometimes, as in the case of a riddle like Brunel/Brownel/Browne, you embrace caution as the better part of valor. I never wrote about who Browne might have been, whether living or dead, natural or supernatural, in God’s Mercies. That was an opening in the ice field I would not permit myself to probe, a lonely figure on a hilltop ridge whose beckoning I declined to follow.

But we nevertheless should recognize how metaphor can organize fact without doing violence to rationalism. With our Arctic passage makers, ideas of transformation, of appearance and disappearance, of replication, resonate. And there are openings in these intertwined stories that do need to be entered.

In the search for a northern passage to Cathay and the Indies that began in the late sixteenth century and proceeded in fits and starts for several hundred years, voyages replicated previous ones in part because observations were so unreliable. Confirmation demanded repetition, and the limited supply of seafarers with sufficient skill and daring lived out versions of past lives. They were given the ships of previous adventurers, sometimes some of their crew, and they took hold of their predecessors’ journals, logs and charts in hope of experiencing and thus affirming what those predecessors had. Sometimes they re-experienced more than they bargained for, and they also perpetuated their delusions.

Although their methodology was rational, they sailed from and into a world that cannot always be bent to satisfy our own rationality. There may not be room in conventional history for Olivier Brunel/Oliver Browne as a boatman of the underworld, but I doubt that the sixteenth-century polymath John Dee, who did more than anyone in the court of Elizabeth I to advance the scientific search for a northern passage to ‘the Indies,’ would give this much argument. Dee consulted archangels via a crystal sphere. James VI of Scotland, who ascended the English throne as James I in 1603, wrote a learned treatise on witches. Brunel as Arctic specter may not have given either Dee or James much pause.

Moreover, the seas these expeditions sailed teemed with strangeness. George Waymouth’s description of the Furious Overfall verged on hallucinatory: the water, he said, was black, different from the blue of the rest of the ocean, and flowed “thicke as puddle [pudding].” Henry Hudson confidently reported on his second voyage in the Hopewell that his crew spotted a pair of mermaids. Of one, Hudson wrote:

from the navill upward, her backe and breasts were like a woman’s, as they say that saw her; her body as big as one of us; her skin very white; and long haire hanging down behinde, of colour blacke; in her going downe they saw her tayle, which was like the tayle of a porposse, and speckled like a macrell.

It’s no use trying to communicate across the centuries and tell Hudson and his men that they actually saw seals or walruses. They knew perfectly well what those were. They would laugh us straight back into the hyper-rational future for doubting their mermaids.

The geography of their passage search was a tangle of false sightings, mistaken identity, and cartographic creativity. In the estimation of Martin Frobisher, who came to eastern Baffin Island in the late 1570s to mine fruitlessly for precious metal, what John Davis would call the Furious Overfall was a dead end. Frobisher’s cartography further compounded the confusion by arguing that the bay at the eastern end of Baffin Island was a strait. So confusing was the late sixteenth-century perception of the eastern Arctic of North America that Davis didn’t realize he was at Frobisher Bay when he traversed its mouth in 1587, and instead named it Lumley’s Inlet. When England’s leading cartographic minds helped mathematician Emery Molyneux create the country’s first terrestrial globe (actually a pair) in 1592, they were sufficiently mystified by these conflicting bays and straits that they located Frobisher Strait 600 miles to the east, bisecting Greenland—an interpretation further codified by Edward Wright in his world map of 1599.

Henry Hudson went looking for the entrance to Frobisher Strait on the east coast of Greenland on his fourth and final voyage. He showed every confidence he was in its vicinity when he remarked in his journal on June 9, 1610 that “we were off Frobishers Streights.” Already Hudson had tried to find Busse Island along latitude 57 North, west of Ireland, which the crew of one of Frobisher’s ships, the Busse of Bridgewater, insisted on having sighted in 1578. The nonexistent landfall was so tenaciously affixed to charts that the British Admiralty would downgrade it to a submerged seamount before giving up on it altogether in the nineteenth century. Earlier on the same passage home, the Busse’s crew reported seeing Friesland, an enormous island south of Greenland that existed only in the fourteenth-century fantasies of the Zeno brothers of Venice, thus helping ensure that their fictions continued to clutter sea charts into Hudson’s time. Hudson also reported sailing along the coast of Desolation, an island John Davis placed on the west side of Greenland that may have been a vast field of sea ice when Davis noted it.

The topography of the passage search was complicated by the limited accuracy of navigation instruments and a highly imperfect understanding of the compass’s workings. Many navigators in Hudson’s time understood there was a difference between magnetic north—the direction to the north magnetic pole, at which the compass needle pointed—and geographic north—the direction to the north geographic pole, which marked the earth’s rotational axis and was key to the scheme of latitude and longitude. But they didn’t know why. Hudson’s right-hand-man, Robert Juet, adhered to the idea William Gilbert proposed in De Magnete in 1600 that there was no such thing as a magnetic pole, that observed directional differences were localized and due to changes in the height of the earth such as mountains and ocean depths. No one even realized until the 1630s that the magnetic pole’s location wandered over time.

Approaching the Furious Overfall, the difference in bearing between the magnetic and geographic poles neared and then rapidly exceeded twenty degrees, a profound challenge to anyone trying both to find their way and to compare what they saw with what their predecessors had recorded.

In 1610 Henry Hudson nevertheless entered the strait beyond the Furious Overfall that now bears his name. He sailed some 300 miles west over the course of a difficult month, before encountering a vast expanse of water to the south. He steered into it, for reasons he never explained or any crewmember understood.

I believe he was looking for a passage Edward Wright had affixed to his 1599 map that was supposed to lead from such a deep bay to a protean concept of the Great Lakes, called Lake Tadouac. That lake in turn was connected by the St. Lawrence River to the Atlantic Ocean, in Wright’s assessment. But in late 1603 or early 1604 the French explorer Samuel de Champlain had argued in his book Des Sauvages that the St. Lawrence drained a series of lakes that were connected by a passage to the Pacific Ocean. Champlain’s book assuredly was known in England. Henry Hudson probably hoped that a passage promised by Wright leading south from what we now call Hudson Bay and James Bay would, via the group of lakes Champlain posited, connect with the passage to the Pacific that Champlain further assured his readers existed.

Hudson’s gamble led him into the greatest cul de sac of any passage venture. He was trapped physically, forced to spend a winter in a corner of James Bay at the south end of Hudson Bay. But he was also isolated psychologically, incapable of confiding in any of his crew what had led him to this point. Even after Hudson agreed in June 1611 to take the Discovery home, enough of the crew decided to seize command, and to consign Hudson and his companions to their unknowable fate.

Mutiny was part of the Discovery’s past. George Waymouth had experienced one on her deck in 1602, as everyone from the master’s mate to the supercargo refused to follow him any further in his adventures beyond the Furious Overfall. Waymouth’s life, however, was spared. The mutineers aboard the Discovery in 1611 were infinitely less generous, as they staged a reenactment not of Waymouth’s bloodless overthrow but rather of another insurrection that had occurred far to the south, at the Virginia colony of Jamestown, in September 1607. That uprising had involved Hudson’s own friend, Captain John Smith, and it overthrew the command of Sir Edward Maria Wingfield.

The record of the Hudson mutiny, in particular the depositions by the survivors—only eight of the original crew of twenty-three made it home—reveals a fascinating episode of repetition. This had nothing to do with confirming the location of a particular bay or an unresolved strait. Instead, the mutineers made every effort to shape the insurrection around a legally defensible precedent. The ringleaders must have been aware of the details of the notorious Wingfield episode. As no one was ever punished for Wingfield’s overthrow, and as Hudson’s voyage shared many leading investors with the Virginia colony, the mutineers did their best to mimic it. The same charges (doubtful in Hudson’s case) that were hurled against Wingfield—of hoarding food while others starved, and playing favorites—were trotted out. Just as mutineers had placed Wingfield in a vessel in the river James while they searched his lodgings for evidence, so Hudson and his associates were persuaded to take to the ship’s boat while the same search was made of Hudson’s cabin aboard the Discovery.

But where Wingfield was allowed back ashore and ultimately returned safely to England, Hudson received no such mercy. The search for evidence hadn’t even begun when the tow-rope was cut, and Hudson and his eight companions were left astern as the Discovery’s sails unfurled. The repeatable became the unimaginable.

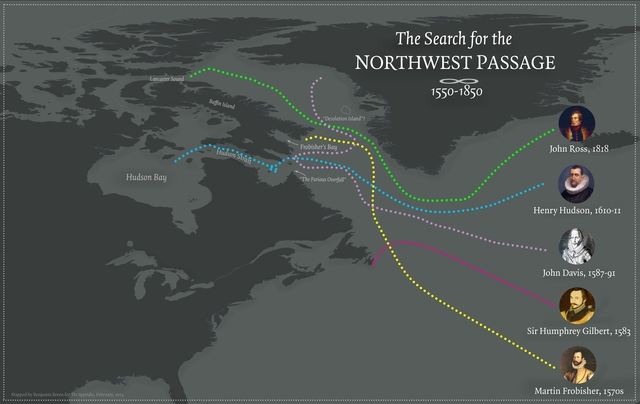

A rough map of the routes sailed by Northwest Passage adventurers mentioned in the text. Benjamin Breen

III. Moving Mountains

Replication and delusion did not end with Henry Hudson. In 1818, John Ross guided a two-ship British Admiralty expedition into Lancaster Sound on the north side of Baffin Island. The search for a Northwest Passage was being reinvigorated; Ross had set out to probe for a passage entrance and survey Baffin Bay, described by William Baffin in 1616. As his partner Baffin had a Hudson crew member, Robert Bylot, whose complicity in the 1611 mutiny remains unresolved but suspicious.

What little survived from that remarkably intrepid 1616 Baffin voyage—a journal version that may not be infallible, a second-hand map—had led some early nineteenth-century critics to question Baffin’s honesty and navigation skills. John Ross was conscious of his role in an act of replication and restoration. With his own explorations, Ross was affirming Baffin’s reliability and skill. This came to a head at Lancaster Sound, so named by Baffin in July 1616. Baffin had not devoted any time to investigating the sound, concluding that it was another hopeless Arctic cul de sac in the search for a Northwest Passage. “How many of the best sort of men haue set their whole endeauoures to prooue a passage that wayes?” Baffin lamented to a backer, Sir John Wolstenholme, on his return. It was Baffin’s last Arctic voyage, and with the passage search temporarily out of momentum, a legal pursuit of Robert Bylot and other survivors of the 1610-11 Hudson voyage resumed. Bylot and three others were tried for murder in 1618. (Mutiny at the time did not exist as a legal concept in commercial voyages.) All were found not guilty, and none were ever heard from again.

John Ross entered Lancaster Sound on August 30, 1818 with two ships, the flagship Isabella and a smaller consort, the Alexander. Ross would observe that because the entrance “exactly answered to the latitude given by Baffin of Lancaster Sound, I have no doubt it was the same, and I consider it a most remarkable instance of the accuracy of that able navigator.” Lieutenant Edward William Parry, who commanded the Alexander, wrote in his journal that day:

Here, Baffin’s hopes of a passage began to be less, every day more than another; here on the contrary, mine begin to grow strong. I think there is something in his account, which gives cause to suspect he did not see the bottom of Lancaster Sound, i.e., whether it were really a sound or a strait, nor have we yet seen the bottom of it.

Yet with tantalizing open water before him, Ross concluded, as Baffin had, that there was no way through. Imagining what he called ‘Croker’s Mountains’ blocking their way, Ross ordered the ships to turn back. Some junior officers were incredulous, and they expressed their misgivings back in England. The following year, Parry returned to Lancaster Sound to prove that the mountains Ross had erected in their path the previous summer were at best a mirage, at worst a delusion. Lancaster Sound led into what Parry labeled Barrow Strait, which he used to sail clear across the Arctic archipelago, some 600 nautical miles west to Melville Island. While sea ice would prevent Parry completing the passage to the Bering Strait that way, Lancaster Sound ultimately proved to be the entrance to the Northwest Passage everyone had been searching for since the late sixteenth century. Baffin, on the brink of a breakthrough, had been wrong not to investigate it, and 200 years later so had Ross.

Who knows how much John Ross was influenced in his 1818 decision at Lancaster Sound by an awareness that he was sailing in William Baffin’s wake, and in the process was either refloating or sinking Baffin’s reputation. Ross’s admiration for what Baffin had accomplished in a far more primitive age of navigation may have produced its own psychological cul de sac: Ross could not deny the ancient navigator his wisdom, and he could not imagine a way into the high-Arctic archipelago beyond the perimeter of Baffin’s experience. His expedition had become fundamentally concerned with salvaging the credibility of Baffin, a fellow Scot. In the process, Ross nearly sank his own.

John Ross returned to the Arctic with a private venture in 1829, now determined to prove the passage and salvage his reputation. He entered Lancaster Sound and turned south down the west side of Baffin Island into the Gulf of Boothia (so named for his backer, the gin distiller Sir Felix Booth). It was another dead end in the passage search’s often tragic history. His ship, an experimental steam-powered vessel called the Victory, became trapped in ice and finally sank. Ross and his men endured four incredible years in this white tomb, aided at crucial times by the Inuit.

In 1833 the survivors made a desperate bid to reach safety in an open boat. Back on Lancaster Sound, Ross confronted an apparition from his misguided past: the Isabella, the ship he had commanded in 1818 when he had decided this very sea passage did not exist. Now a whaler, the Isabella gathered up the Victory’s men and sailed Ross back through the mirage of Croker’s Mountains that he had once spied from her very deck. The impossible had become the implausible.

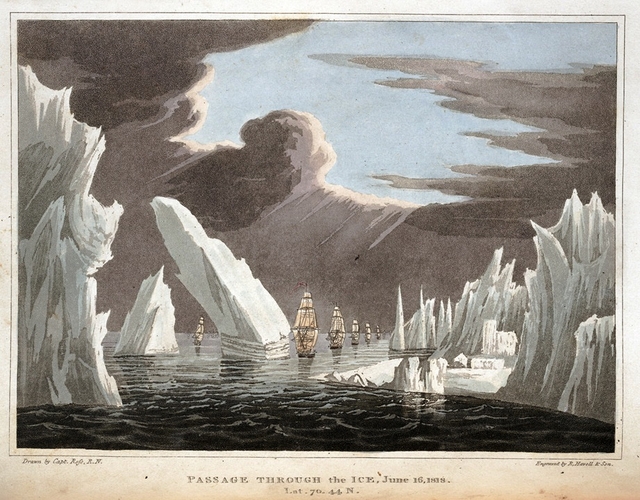

“There is something in his account, which gives cause to suspect… we have not yet seen the bottom of it.” Benjamin Breen, 2013, after Friedrich

IV. The Matter of the Carpenter and the Boy

I will leave you with two of the more curious narrative threads of the Hudson mutiny that speak to appearance, disappearance, and reappearance. The first involved Henry Hudson’s son, John.

In 1613, John Hudson became the object of a rescue attempt by the French explorer Champlain, whose book Des Sauvages may have led Henry Hudson into the cul de sac that claimed him. Champlain had been told by a young Frenchman, Nicolas de Vignau, an interpreter trainee who had been living with the Kichesipirini, an Algonkian-speaking people of the Ottawa River, that he had made a journey with them to the Northern Sea. He had seen the wreckage of an English vessel, and had learned that a neighboring nation of the Kichesipirini, the Nebicerini, were holding an English boy captive from that wreck and wanted to make a gift of him to Champlain. The story made sense from what little was known back in France about the Hudson mutiny of 1611. With de Vignau as a guide, Champlain set out to collect the English boy and hopefully reach the Northern Sea himself.

That venture ended in terror and confusion in the Kichesipirini summer camp on the Ottawa River. Accused by the Kichesipirini of lying about the existence of the English boy and of ever having been to the Northern Sea, Nicolas de Vignau barely escaped with his life, although Champlain then abandoned him to “the mercy of God” and an unknown fate at present-day Montreal. The fate of the English boy too remained unresolved: Champlain couldn’t seem to decide whether what de Vignau had told him was the truth, a lie, or something in between.

Also lingering in the background of John Hudson’s cryptic fate is whatever became of the ship’s carpenter, Philip Staffe.

The mutineers had wanted Staffe to stay aboard the Discovery, to help ensure the ship endured the difficult voyage home, but once it was clear that the men who had been coaxed into the ship’s boat would not be allowed back aboard, Staffe would not hear of remaining. One survivor, Bennet Mathew, attested that Staffe threatened to jump on the first ice floe that passed by if the mutineers made him stay. The mutineers obligingly assigned Staffe to the boat, a large open craft called a shallop, allowing him his chest of personal belongings, along with other supplies.

The admiralty court’s questioning of survivors in 1617 revealed an unusual suspicion as to the fate of Staffe. Robert Bylot avowed that the carpenter had gone into the boat “of his own accord, without any compulsion; whether he be dead or alive, or what has become of him, he knoweth not.” The voyage’s supercargo, Abacuck (Habakkuk) Prickett, was also asked to address Staffe’s fate. His recorded reply: “he sayth he doth not knowe whether the shipp carpenter be deade or alive, ffor as he sayth he never sawe him since he was putt out of the shipp into the shallopp.” Still the court persisted in this line of questioning. Another survivor, Francis Clement insisted that Staffe was among those committed to the boat and that he had no idea whether Staffe was dead or alive.

The admiralty court seemed to be pressing survivors for evidence that Staffe was actually alive—as if the carpenter, against all odds, had been spotted strolling the streets of his native Ipswich. The court may have been suspicious of the fact that Staffe’s chest was the only one belonging to a castaway that hadn’t returned with the Discovery when she regained London.

When writing God’s Mercies I stared into the opening that this strange pattern of interrogation seemed to create: Staffe was neither an official victim nor an official survivor. Perhaps he had made a deal with the mutineers. He would stay aboard and help them get the Discovery home, but would be off the ship at the first opportunity, and no one was to be the wiser. Staffe was supposed to have been deeply loyal to Hudson, but Hudson had been so angered by Staffe’s initial refusal to build a shelter for the overwintering in James Bay that he had threatened to hang him. And so perhaps Staffe had made his bargain and slipped away when the Discovery first reached England, at Plymouth, taking his chest with him, before the ship moved on to its final destination of London. The survivors had been good to their word and insisted he had last been seen far astern of the Discovery with Henry and John Hudson and the rest in an ice-strewn James Bay.

That opening, that possibility of a living dead man, remains unexplored. You are welcome to see where it leads.

Further Reading

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2SwU7iB

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.