The status of dance in American culture is deeply paradoxical. Concert dance is one of the most elite art forms imaginable. The demands placed on professional dancers are so punishing that those of us who live outside this spartan vocation may struggle to understand the labor involved. Dancers are, in the words of the choreographer William Forsythe, “Olympic-level athletes” whose aim is a perfect synthesis of athletics and artistry. This takes years of training and enormous sacrifice—and for what? An audience composed of a sliver of the urban intelligentsia; a career butterfly-like in its brevity, inevitably cut short by age or injury.

And yet: Dance is also spontaneous, elemental, universal. Cave paintings show that humans have been dancing since at least the Stone Age. Some scientists, having observed that chimpanzees occasionally sway and clap while listening to piano music, believe that the desire to dance predates humanity. Psychologists have argued that group dance supports social bonding. Anthropologists, meanwhile, have found expressive or ecstatic movement at the core of many religious rituals: healing rites, initiation ceremonies, funerals, weddings, preparations for war. Dance returns us to the earliest mysteries of human creation. It is one of our fundamental arts.

Much contemporary choreography emphasizes virtuosity and difficulty, incorporating aerial or acrobatic movement or feats of physical daring. (The choreographer Elizabeth Streb’s 1995 piece Breakthru, for example, requires a dancer to leap through a pane of glass.) But today’s artists are also keenly interested in integrating everyday movements into dance. Some choreographers have turned to amateurs instead of trained performers. Others have highlighted such mundane actions as walking, skipping, kneeling, or toe-tapping in their works. Such performances narrow the distinction between offstage and onstage movement, reminding us that dance is ordinary and ubiquitous. By making dance resemble life, they show us how life, in turn, resembles dance.

Annie-B Parson’s new book, The Choreography of Everyday Life, makes a more radical claim, rejecting the distinction between dance and life altogether. Parson, an acclaimed choreographer best known for her genre-bending work combining dance with theater, offers an exuberant, if lightly sketched, conception of human life as a collective dance, winding and unspooling in endless variations as we move through time and space. For her, dance is not a rarefied form. It is more like the natural, everyday motion of strolling down the street, which, after all, involves considerations of line, space, and tempo. City life, especially, requires dancelike coordination: Strangers streaming down the sidewalk must find a “group rhythm.”

If we look at the world through Parson’s eyes, we find that dance is all around us, in people stretching or hugging or standing in line. We are all “natural choreographers,” continually navigating through space. Such a blissfully aesthetic attitude may strike us as Pollyannaish: life as a cabaret. But even the most committed melancholics have found in dance a model for life lived in time, bound to constraints but offering chances for creative response. No less pessimistic a poet than W. B. Yeats selected dance as his image of how human beings express themselves through action: “O body swayed to music, O brightening glance, / How can we know the dancer from the dance?”

Choreographers often describe dance as a language. It works its effects in part through what the critic John Martin called “kinesthetic sympathy”: The viewer, in a kind of “inner mimicry,” imagines what it would feel like to carry out the movements she sees. (This concept explains why some of us wince at contortionists.) Bypassing speech to hit the body, dance can elicit a muscular as well as an emotional response, conveying ideas and feelings that resist language, even predate it.

Read: Why the dancing makes ‘This Is America’ so uncomfortable to watch

For the legendary American dancer and choreographer Martha Graham, what defined the language of dance was truthfulness. “Movement never lies,” she regularly said. An arresting speaker with a flair for gnomic utterance, Graham never rejected verbal communication; she read constantly, especially poetry. But dance was her “letter to the world,” the mode in which she communicated her ideas, perceptions, fears, and longings. Graham’s achievement, as Neil Baldwin details in his new biography, Martha Graham: When Dance Became Modern, was to take the language of classical dance and explode it, discovering new expressive possibilities by introducing movements that many viewers found grotesque or disturbing. The result was the making of modern dance.

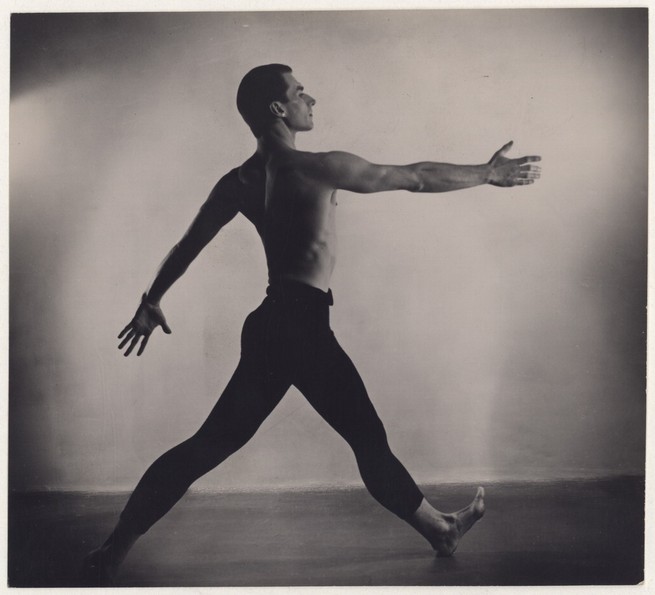

Baldwin follows other dance critics in affirming Graham’s place at the vanguard of a new kind of dance. Before Graham, the critic Joan Acocella writes, “there was basically one kind of concert dance in America: ballet.” After Graham, there were two: ballet and modern dance. Bristling against what she saw as the artificial prettiness and mannered constraints of ballet, Graham developed a movement vocabulary that was harsh, angular, percussive. Ballet specializes in soaring leaps and curved, symmetrical movement. Graham’s style, Baldwin shows, was earthbound and visibly effortful, involving falls and floorwork performed from seated, twisted, or supine positions. By developing new ways for dancers to move, Graham allowed them to say new things with their bodies.

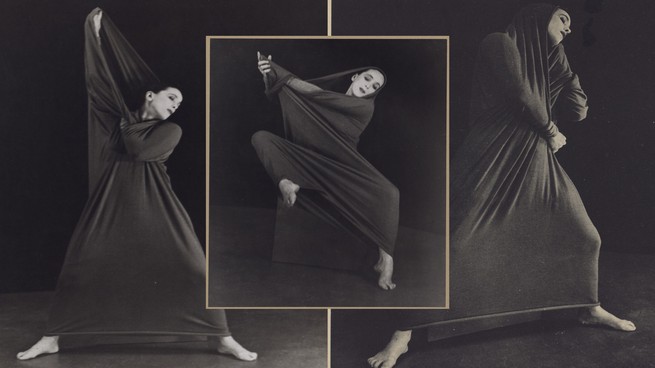

In her 1930 solo piece Lamentation, for example, the dancer is sheathed from head to ankles in taut purple fabric, creating diagonal lines of tension by pushing against the cloth, as if trying to escape from the folds that envelop her. Graham’s program note described Lamentation as “the personification of grief.” Much like the dancer twisting and elongating the purple tube garment, Graham expanded the boundaries of dance to include raw psychological material. Sometimes, these difficult topics were political. In her breakthrough piece, Heretic, Graham is dressed in white and rebuffed and rebuked by a group of 12 women dressed in black: the punishment of the nonconformist. More often, they were erotic, even outrageously so. In Night Journey, her 1947 adaptation of Oedipus, Graham, as Jocasta, ensnares Oedipus in a rope evoking an umbilical cord. She brought dance closer to ordinary experience by admitting onto the stage certain dark corners of the soul that ballet had leaped over.

Even while Graham made dance more responsive to grief, eroticism, and other elements of real life, she also moved hard toward abstraction. Baldwin notes that early in Graham’s career, on seeing a Kandinsky painting for the first time, she reportedly marveled at his expressionist bursts of color, the streak of red crossing the canvas. “I will do that someday,” she pronounced. “I will make a dance like that.” This story may be apocryphal; Baldwin gives us reasons to doubt it. What is beyond doubt is Graham’s affinity with nonrepresentational art, aimed not at telling a story but at conveying deep emotions and fundamental truths. Dance, for Graham, was a universal language.

Parson, too, sees dance as a powerful form of communication—and a way of speaking on a level deeper than language. One of dance’s key functions, according to Parson, is its role in political assembly. Marches, lie-ins, sit-ins—“These acts of protest,” she argues, “are choreographies: the body in space has intentional directives agreed upon by the performers.”

Read: The company working to make dance more inclusive

Parson’s insights are a welcome reminder of the political value of dance, which has long served as a powerful aid to protest, its expressive beauty lending eloquence to public demonstrations of outrage or sorrow. The Oakland dance crew Turf Feinz, for example, attracted wide admiration for a 2009 video recorded on a rainy street corner, mourning the death of a dancer’s half brother. Gliding across the rain-slicked asphalt, the dancers spin, pop, and lunge, incorporating elements of ballet and boogaloo. One dancer, in red, holds a pose outside the crosswalk, his arm and leg thrust back in sharp diagonals, forcing a passing car to maneuver around him. This defiant claiming of space is a common feature of protest dance. More recently, the dancer Jo’Artis Ratti approached police officers during a protest in Santa Monica following the murder of George Floyd and began krumping, his rippling, jabbing movements becoming a poignant expression of anger and despair. Such moments, Parson might argue, show the urgent possibilities of dance, while also illustrating Graham’s insight that the body says what words cannot.

As the American composer John Cage once remarked, formal theater exists to remind us that theater is already happening all around us. So it is with dance, which pays tribute to the rhythms we share—inhale and exhale, systole and diastole—as we move together through time. T. S. Eliot in Four Quartets, which the choreographer Pam Tanowitz stunningly adapted into one of American dance’s most important recent works, states the matter well. “At the still point of the turning world … there the dance is.”

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/3XgsSdT

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.