Europe was a new land, and one ripe for conquest, and a warm reception on the northern shores of the Mediterranean further strengthened the bond between human and feline . . . or so we thought. Centuries of adoration had left us blind to what was to come. This new land would later bring us to our greatest despair, as it was there that we met with the treachery of man, and thereafter struggled to survive against cruelty of a kind no other species has ever suffered. But we will leave the dark days for later in our tale. For now, sail on through bright skies, being the brilliant blue that hung over the Greek docks—where the Phoenician sailors were unloading their marvelous cargo.

We were seen as a living miracle when the first ships carrying us arrived. This was some seven or eight centuries before the common era, and the Greeks were still a crude people who knew only of roughand-tumble wildcats. The domestic variant appeared to them as wondrous. They were entranced by the softness of our fur and amazed by our gentle personalities. Why, we were amenable to the touch, and even—well, depending—allowed humans to hold us in their arms! “But they are so much more than novelties,” the traders exulted, “for these cats are also useful!” They explained how we were far superior to the mousers the Greeks had previously relied upon. Oh, sure, weasels and martens could kill vermin, but they were wild creatures, indiscriminate hunters who might eat your chickens too.

But these were genuine Egyptian felines, domesticated animals who could be relied on (well, in theory) to kill only the desired rodents. The Phoenicians were nothing if not brilliant pitchmen, and it took little convincing before the Greeks were sold. They even agreed to pay added premiums for black cats—they were the most effective hunters of all, the merchants claimed, since their dark coloring made them invisible to their prey! Is that so? Ha, no! Mice have highly refined senses of smell and hearing, which they rely upon in the darkness instead of sight, thus making the color of the cat entirely irrelevant. Yes, a sucker is born every minute, but in the excitement, no one seemed to be bothered by such details.

The people of the northern Mediterranean were rank amateurs when it came to cats back then. But they had expertise in another field, and it was there that they offered their most important contribution to our history: words. Initially, the Greeks called us galê, being a catchall for small mammals and the same word they used for weasels, since at first we were all considered to be in the same category. Hmph! But by the fifth century BC, new words were evolving, and they are still with us today. Feles came into use first, eventually being replaced by feline, and this was followed by catta, from which the modern English cat, as well as chat, gato, katze, and all the other similar-sounding variations in the many human tongues are derived.

A popular legend also gave birth to another—albeit less pleasant—word. The story involved a cat named Aielouros. The name was derived from the words aiolos, meaning “to move,” and ouros, meaning “tail”—in effect, the “tail wagger.” The loveliest of all felines, she was transformed into a human woman of such beauty that she rivaled no less than Aphrodite, so as punishment, the spiteful goddess transformed her back into her original form. The story itself was hokey and marked the predictable presumption of your kind (what makes any of you think we would prefer to be human than feline?), but from it the term “ailurophobe,” being a person with an irrational fear or hatred of cats, was born.

The domestic variant appeared to them as wondrous. They were entranced by the softness of our fur and amazed by our gentle personalities.This was still the golden age, however, and other than cranky Aphrodite, there were scarcely any ailurophobes to be found in what was rapidly becoming a country of ailurophiles—the word for cat lover. Eager to share their newfound wonders, the Greeks picked up where the Phoenicians had left off, carting us even further afield as their own power and prestige grew. Cats were again on the move, and oh how far we traveled! Greek colonists brought us to outposts in the Balkans and along the Black Sea, and to their settlement in Massalia—perhaps you know it better as Marseille, France? From there, it was an easy cruise with local traders up the Rhone River into Germany.

Italy was also introduced to cats through the Greeks, who brought us to their colonies in Sicily, from whence we made our way up the Italian peninsula. And by the time we got to Rome, well . . . what Caesar saw, Caesar conquered, and we followed in his wake. We had been entreated to join his armies in order to protect Roman stores from vermin, and, locked in step with the Imperial Legions, we marched all the way to Britannia.

“Hardly such a triumph!” the skeptics will scoff. “Were you not taken into servitude and carried about the continent as nothing more than forced labor?” I will not deny that we were introduced to Europe as humble mousers, but we knew the winning formula that had been passed down since the days of little Felis: through diligent work safeguarding the supplies of humans, we once again earned a place in even the most hardened of hearts. And if you trust not my word, consider the fondness of the Roman soldiers for us, as they were the first to adopt the domestic cat as a heraldic animal. Why, not even the Egyptians had gone so far, their army preferring the lion-headed Sekhmet. But the Roman Ordines Augusti marked their shields with the image of a green cat, and the Felices Seniores with one in red.

Of course, up north, many of Caesar’s soldiers were mercenaries rather than being Roman by birth, and this provided a further boon to our conquest. The cats who had traveled with the legions were assigned to fortresses and would not typically have been seen outside of them. Had the soldiers been entirely Roman, we would have remained a secret, but locals serving among them had a chance to learn firsthand of our virtues. And so it was that even as the power of the empire ebbed, ours grew greater still. When the great battlements were abandoned, we returned not to the Eternal City, but were claimed as prizes by men-at-arms hired from nearby villages, who took us with them to their homes.

And as we prospered in these new communities, our triumph in the end turned out to be even greater than the mighty Caesar’s. It’s true, my friends! I don’t wish to embarrass the Imperial Throne too badly, but it was left to Rome’s felines to complete the conquest of which Trajan had only dreamed; consider that his army was stopped by warring tribes and never succeeded in breaching Scotland . . . but we did. And by cuddles and purrs, rather than blood and steel. But we pressed on further still, forging boldly ahead on merchant ships toward Scandinavia, to those rugged northern climes from which the mighty Vikings would emerge.

The Greeks were quick to accept the sacred nature of cats and declared us to be companions of Artemis, and the Romans followed suit with Diana.To other humans, these fearsome Norsemen were nothing less than a terror. Ah, but to us they fell meekly. Their strong, calloused hands, marked by the scars of battle and stained with blood, became for us soft palms as they put aside their axes in exchange for the simple joy of stroking warm feline fur on frostbitten nights. Why, they were so enamored that they specially bred us to serve on their ships, this heritage being preserved in the modern Norwegian Forest cats. So shall we end a debate right here and now? Should any among you think there is an effeminate stigma about being a “cat guy,” well, feel free to take the matter up with a Viking.

As the pagan world was ever sympathetic to our kind, our newfound human friends continued the tradition of sharing their spiritual lives with us. The Greeks were quick to accept the sacred nature of cats and declared us to be companions of Artemis, and the Romans followed suit with Diana. Both of these goddesses possessed the ability to take on feline form, and Artemis in particular was so closely associated with domestic cats that it became a staple of Greek lore that it was she who had created us.

And we had not arrived in Europe with empty paws, having brought the feline archetype constructed by the Egyptians to further augment the powers of our new patron deities. Artemis and Diana became protectors of the domestic realm, guarantors of well-being, and champions of fertility. And carrying on the Egyptian tradition of associating felines with lunar deities, both also became patrons of the moon. We even accompanied Artemis as she rode upon her chariot each evening to pull its great silver disk up into the night sky, a phalanx of cats following in her wake to gobble up the mice of twilight.

But as estimable as those goddesses were, they did not completely meet our needs. What of the feline’s affinity for magic? The Greeks and Romans likewise sensed it, and for this reason gave us union with Hecate. Enduring goddess of mystery, she ruled over those arcane things which humans could sense but not see. Her powers were wielded over the underworld, liminal spaces, dreams, and magical practice, and it was she who was invoked by all of the famed enchantresses of the classical world, including Circe, Medea, and the Witches of Thessaly. I’m sure it will come as no surprise to learn that her shrines were often populated by cats, and once again black ones in particular, since a shared affinity for night gave them a natural connection to the goddess.

Hecate even took in a troubled stray as a companion—and giving credit where credit is due, history’s first recorded rescue cat was thus a product of Greek mythology. Her name was Galinthias, and she had formerly been a human maid of Alcmene, the woman whom Zeus had impregnated as the mother of Hercules. Hera was furious over this act of infidelity, and endeavored to stay the birth. But clever Galinthias distracted the goddess long enough that her grip was loosened. In retaliation, Hera changed Galinthias’s form to that of a cat. Hecate in turn took her in, having recognized in Galinthias’s sacrifice a perfect example of feline loyalty. A precedent was thereby set, and Hecate’s priestesses were spurred to seek out their own feline confidants, thus giving birth to the tradition of sorceresses owning cats—and not as “witches’ familiars,” mind you, but as ideal spiritual companions!

Anywhere you looked in pagan Europe, it was the same. As far away as the northern realms, the Vikings also considered us as spiritual beings. They declared us consorts of the flaxen-haired Freya, yet another goddess associated with domestic bliss and fertility, and she and her cats were inseparable. Why, they even provided her locomotion by pulling her carriage through the sky as she traveled the land to bless the harvest. Ah, perhaps there is some confusion among my readers. But Baba, wasn’t Freya the fierce warrior goddess who led the Valkyries to battle? Yes, one and the same!

__________________________________

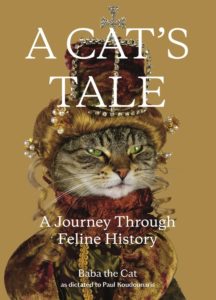

From A Cat’s Tale by Paul Koudounaris and Baba the Cat. Used with the permission of Henry Holt & Company. Copyright © 2020 by Paul Koudounaris.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/3npbWdB

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.