The area that was once home to the notorious St Gile’s Rookery is today home to one of the most expensive shopping areas in London, and is identified with indulgent displays of wealth. The New Oxford street road runs through what was once a vast triangle of poverty, deprivation and crime, and though now lost, it was an infamous London landmark for centuries.

The area of St Giles-in-the-fields took its namesake from the chapel and hospital that was built in the 12th century by Queen Matilda, who founded the building for sufferers of leprosy. St Giles is the patron saint of lepers, but he is also considered to be patron of outcasts, vagabonds, cripples and the like, which became synonymous with this area too (Peter Ackroyd, 2000, p.131). There had always been connotations of uncleanliness and ill health with St Giles, and it was widely thought that the first victims of the Great Plague lived in the parish.

The area had seen some wealth in the 17th century, however the locality of the area was an attraction for poor foreigners fleeing safety and unrest in their own countries, which lead to an influx of Irish, French, and other nationalities which saw an increase in the already growing population. The district had become divided by wealth, and the next century saw the wealthy move further up west and the poor congregating into small, congested communities, and living in dire poverty. One outcome of this deprivation the under classes experienced was The Rookery.

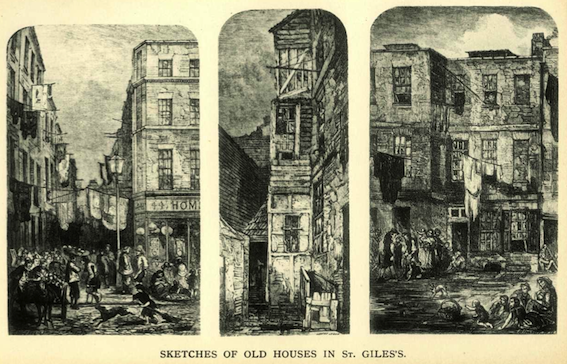

The Rookery was a maze of streets, lanes and alleys and with the principal area being “enclosed by Great Russell Street, Charlotte Street, Broad Street, and High street” and “within this space were George street, Carrier Street, Maynard Street and Church street” (Henry Mayhew, 1860). It was a “endless intracity of courts and yards”, and was home to pubs, lodging houses and the livelihoods of the impoverished (Henry Mayhew 1860).

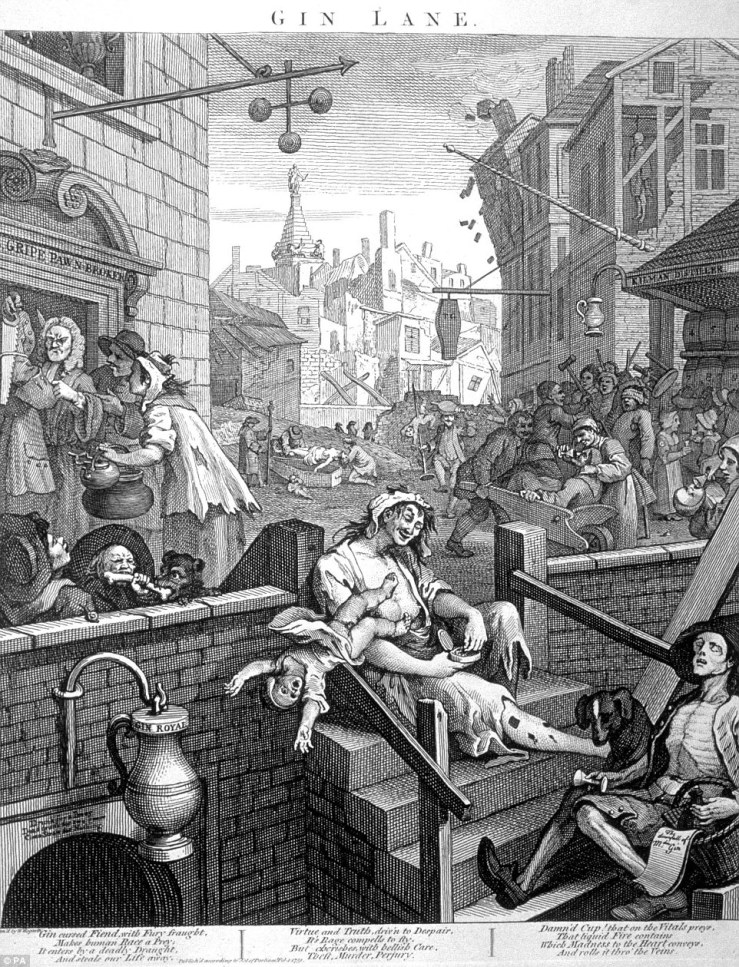

In the 18th century the Rookery was a home to the “Irish and aliens, beggars and dissolute and depraved characters”, and William Hogarth created a series of prints with inspiration garnered from the residents of ‘Little Ireland’ or ‘The Holy Land’ as it was known. Gin Lane is a representation of the poor from this slum, and drink was deemed the root cause of their problems. Peter Ackroyd calls Hogarth ‘uncannily prophetic’ of what The Rookery would become, and the levels of squalor in the slum showed no signs of slowing down(Peter Ackroyd, 2000, p.133). The residents in these slums were not seen as victims as we would sympathise today, but seen as victims of themselves; they had succumbed and created the destitution and deprivation they had found themselves in, and the genuine poor were viewed no differently to the criminals they shared the streets with.

In 1771 ‘The New London Spy’ was published, and its author went on a tour of St Giles due to its poor reputation, from Covent Garden to Seven Dials . It’s a sensationalist account, but it gives us a valuable insight into how the Rookery, its residents and the poor in general were received in the 18th century. The narrator enters the slum with “as much glee as a country man does a booth in Bartholomew Square”, and comments how “theft, whoredom, homicide and blasphemy were legible in every face” (Richard King Esq, 1771, p144). The understanding of the residents was one that came from fear and disdain, they were almost an attraction to visit and were seen separate from other parts of London society; they were essentially viewed as a mob, or in his companion’s words;

“A corporation of whores, coiners, sweaters, highway men, bawds, pickpockets and house breakers… In search of opportunities to exercise their villany”. (Richard King Esq, 1771, p.145)

The Rookery was seen as its own district, as the law enforcers wouldn’t venture into a deep maze of courts and tenements with little or no knowledge how to navigate its alleys and gateways. This mob mentality was partly true, due to gangs forming in the Rookery and operating in the close upmarket West end, and then retreating to safety in the courts and alleys. Catherine Lineham, a 17 year old thief, a member of an Irish gang run by Redman Keogh, took a house in the streets of the Rookery, purposefully to use as a place to rob victims after they had been pressed to drink themselves into a stupor. She talked of “biting the culls of their scouts” and also robbing a “Rum Fem”; robbing people of their watches and a diamond ring to you and me (Old Bailey Proceedings, July 1741, Catherine Lineham, (OA17410731). These terms may well have been a part of the vernacular known as ‘St Giles Greek’, slang vernacular unique to the area and its residents, and was particularly helpful evading any law enforcers finding out people’s illegal activities.

The turn of the next century led to crime, prostitution and filth reaching new heights in The Rookery, and special houses called ‘Cadging Houses’ were being let out, which were essentially Vagabond houses. An exploration into the area in 1835 called Dens of London, considered itself the first expose on these houses and its inhabitants. These houses had gathered more prominence as the poverty raged on, and in what Duncombe calls ‘modern Sodom’, he investigates what these houses that were so common were (John Duncombe, 1835, p.22). Thieves, prostitutes and ‘trampers’, (one night lodgers), rented out rooms in these houses, and they were viewed to breed criminality. Duncombe meets one youth who ‘Hogarth or Joe Lisle..might have taken this youth for the very Son of Idleness’, insinuating Hogarth’s prints had finally come to life, and this youth by his own admission tells of how St Giles and prostitutes were the ruining of him, and it’s made clear in The Rookery you couldn’t get one without the other (John Duncombe, 1835, p.33). A fellow called Charles Dickens also visits the Rookery in this period, and he records ‘scenes of a most repulsive nature’, and how the residents suffer ‘forms bloated by disease and faces rendered hideous by habitual drunkenness’ (Charles Dickens, 1836, p.16).

The Rookery had always been notorious but in the 19th century, it was raising social and moral questions, such as class divide, wealth distribution and exploitation from landlords and this started to gain attention, but it was the slums proximity to the west end that shocked the London City council into action. One such action was in 1847 the inner part of the Rookery was cleared for the New Oxford road, and displaced many residents, who simply crowded into the remaining streets such as Church Lane.

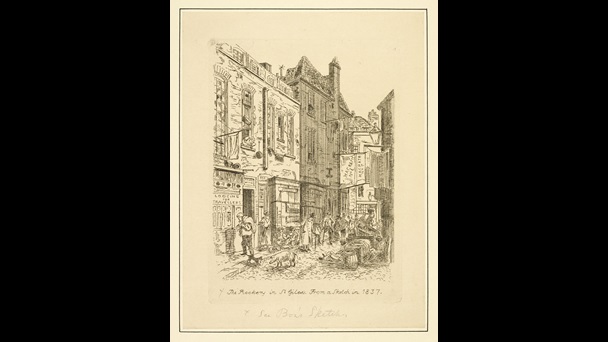

Thomas Beames in 1852 published his visit to St Giles in The Rookeries of London , which he visited after the demolition and was outraged that people thought the issue of the poverty was solved, and seethed;

‘The Rookery is no more! A spacious street is in its stead; but will you tell us that any poor man has gained by the change; that any section of the working class has reaped an advantage….’

Beames calculated that in Church Lane over 1000 people were crammed into one street, and he realised that the ‘plague spots from that colony’ still very much existed; this poverty and deprivation couldn’t be solved by simply eradicating the Rookery (Thomas Beames, 1851, p.30-41).

Nothing survives of the Rookery today, only a few street names would be still recognisable to the dwellers that lived in its maze, but its memory is a testament to just how divided London can be for the social classes and it wouldn’t be so hard to imagine in modern times how a group of people could be so disaffected and disadvantaged by society that they would have to resort to slum living to survive; one only has to look across the channel to places such as Calais to realise this.

____________________________________________________

Bibliography:

Books:

Charles Dickens, Sunday Under Three Heads, J. W. Jarvis & Son, 1836

Henry Mayhew, London Labour and the London Poor, OUP Oxford, 14 Oct 2010

John Duncombe, The Dens of London, 1835

Peter Ackroyd, London; the Biography, Chatto & Windus, 2000

Richard King, The New London Spy: Or, a Twenty-four Hours Ramble Through the Bills of Mortality. Containing a True Picture of Modern High and Low Life; … The Whole Exhibiting a Striking Portrait of London, as it Appears in the Present Year, J.Cooke, 1771

Thomas Beames, The Rookeries of London: Past, Present, and Perspective, T.Bosworth, 1852

Online:

Old Bailey Proceedings Online, (https://ift.tt/Q3ujxs, version 7.2, 06 December 2017) Ordinary of Newgate Account, July 1741, (OA17410731)

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/3i5AIg7

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.