This essay will hopefully be the first post in a series covering some of the basics of how things in the past, particularly in the ancient world, were made. This isn’t a how-to guide (we’re not going to go into that much depth) but instead intended as a window into the many tasks that made a pre-modern society work, tasks that are so often left out of the modern imagination of the past. Throughout, I want to highlight not only the jobs, but also the people who did them and the human landscapes they created.

Each entry in this series is likely to come in multiple parts – as you will soon see, almost everything worth making has to be made in quite a few steps and each step is often complex enough to occupy its own weekly post. I think this series will run in four parts (possibly with a fifth part addendum), but no plan survives contact with my tendency to overwrite. I wanted to start with farming instead of something more flashy and exciting like iron production (where I know there is quite a lot of interest in how one goes from reddish rock to polished sword), for the simple reason that agriculture sits at the foundation of every other form of production. Every person in an agrarian society whose job – mining, smithing, tanning, timber-cutting, trading, tailoring, everything – doesn’t involve primary food production is subsisting off of the food production of others, typically (as we’ll see) many others.

That said, this post is mostly about farmers more than farming (we will talk about the mechanics of farming, just not right away!). One thing I want to highlight in this series are the many different jobs and occupations and the people who did them who tend to lurk in the background of our imagination of the past, where they appear at all. And in the case of farming in much of the pre-modern world, the survival strategies of subsistence farmers exert a very strong shaping influence on the countryside and life for non-farmers (terminology note: ‘subsistence’ farming refers to farming directed primarily towards the survival of the farmers and their families; in much of the pre-modern world, there was a fairly sharp divide between most farmers who farmed on a subsistence basis and the largest market-oriented estates of the wealthy, who will be our focus next week).

As a final caveat before we dive in, I specialize in the economy of the ancient Mediterranean, so my observations here are going to tend (where not otherwise noted) to be most true in the Mediterranean world, in that period (c. 650 BC – 450 AD). Where I know there are major exceptions, I’ll try to note them, but it’s simply not possible to know every production permutation everywhere and at every time. For this series, we’re going to focus on wheat production, with a bit of a Mediterranean bias (but I’ve tried to pull in some evidence from North China as well; by and large I’ve found that wheat cultivation seems to create similar patterns everywhere, but there is local variation).

As always, if you like what you are reading here, please share it; if you really like it, you can support me on Patreon. And if you want updates whenever a new post appears, you can click below for email updates or follow me on twitter (@BretDevereaux) for updates as to new posts as well as my occasional ancient history, foreign policy or military history musings.

Bibliography note at the outset: for the sake of keeping these posts readable, especially since I don’t have an easy footnote function here, I am not going to laboriously cite everything at each point of reference, but I’ll include a bibliography note up front for the whole series. My information for the ancient Mediterranean is drawn from a number of sources, the most important of which are P. Erdkamp, The Grain Market in the Roman Empire (2005); N. Rosenstein, Rome at War: Farms, Families and Death in the Middle Republic (2004); Foxhall and Forbes, “Σιτομετρεία: The Role of Grain as a Staple Food in Classical Antiquity,” Chiron 12 (1982) and Foxhall, “The Dependent Tenant” JRS 80 (1990), and just reading a pile of Greek and Roman agricultural writers (Columella, Cato, Pliny the Elder, Xenophon, etc).

Note also C. Fischer-Bovet, Army and Society in Ptolemaic Egypt (2014), W. Scheidel, Death on the Nile (2001) and R. Bagnall and B. Frier, The Demography of Roman Egypt (1994) for the Egyptian demographic modeling. Egypt is an important reference for demographic data because relatively more records survive there due to the arid conditions preserving papyrus.

I am less well read on Medieval European agriculture, but I should note some reliance here on M. Bloch, La Société Féodale (1940; available trans. Manyon, 1962) and E.L.R. Ladurie, Les Paysans de Languedoc (1966; available trans. J. Day, 1976). Also relevant on general features and broad continuity, J. Landers, The Field and the Forge (2003); for the military history minded, Landers (and Rosenstein) are more focused on the connection between agriculture and military activity.

My references to Chinese agriculture are from Cho-yun Hsu, Han Agriculture: The Formation of Early Chinese Agrarian Economy (1980).

Why Bread?

From the outset I want to note that agriculture, especially subsistence agriculture, typically is not planting simple mono-cultures of a single crop. I opted to focus in this series on bread because it is usefully simple for a number of reasons. It lets us focus on wheat and barley, which are relatively simple crops to talk about but also (in the broad sweep of Eurasia where they were the primary crop) provided the majority of calories for the vast majority of people. Vegetables, fruit, meat, other animal products (along with sauces and things derived from them) were in the ancient Mediterranean generally expensive things, used by most normal people (read: the not-super-rich) to flavor a meal that still consisted mostly of bread, when they were available at all. That’s because (as we’ll see) wheat and barley were efficient and cheap to grow at scale.

That doesn’t mean that people only ate bread, to be clear. The Mediterranean diet is built on a triad of grapes, grains and olives; animal products were also in the diet. Grains don’t have a broad enough range of nutrients to really subsist someone forever; you need proteins and vitamins and so on. But when we are looking at the bulk of what was eaten any way we measure it – calories, volume, weight, labor intensity, economic scale – cheap, mass-available grains just dominate, so that’s where we start. When scholars model ancient agriculture and food habits, they build a nutritional model centered on grains and then supplement with other things as necessary (which as an aside is also how the Greeks and Romans actually talk about food – rations that we are quite sure included meat and vegetables are typically given as grain allowances, e.g. Thuc 4.16.1; Plut. Lyc. 12.2; Plb. 6.39.13; Cato, de Agr. 56).

Finally, a terminology note: when I say wheat I mean genus triticum and its subspecies; when I say barley I mean Hordeum vulgare. I am going to use ‘grain’ or ‘grains’ to refer to both crops together (although there are many other grains). The British frequently use the word ‘corn’ to refer to wheat; this causes no end of confusion in Americans, for whom ‘corn’ means maize. I do not know that I will reference maize, but if I do, I will call it maize and to avoid confusion, I am not going to use corn at all as a term. Apologies to my British readers whose usage is, I should note, older but also more confusing.

To start with, we need to start not with our crops, but with our farm and farmers.

The Farming Household

Looking at our peasant household, what we generally have are large families on small farms. The households in these farms were not generally nuclear households, but extended ones. Pre-Han Chinese documents assume a household to include three generations: two elderly parents, their son, his wife, and their four children (eight individuals total). Ptolemaic and Roman census data reveal a bewildering array of composite families, including multi-generational homes, but also households composed of multiple nuclear families of siblings (so a man, his wife, his brother and then brother’s wife and their children, for instance), and so on. Normal family units tended to be around eight individuals, but with wide variation (for comparison, the average household size in the United States for a family is 3.14).

At the same time that households were large (by modern standards), the farms they tilled were, by modern standards, very small. The normal size of a Roman household small farm is generally estimated between 5 and 8 iugera (a Roman measurement of land, roughly 3 to 5 acres); in pre-Han Northern China (where wheat and millet, not rice, were the staple crops), the figure was “one hundred mu (4.764 acres)” – essentially the same. In Languedoc, a study of Saint-Thibery in 1460 showed 118 households (out of 189) on farms of less than 20 setérée (12 acres or so; the setérée appears to be an inexact unit of measurement); 96 of them were on less than 10 setérée (about 6 acres). So while there is a lot of variation, by and large it seems like the largest cluster of household farms tend to be around 3 to 8 acres or so; 5 acre farms are a good ‘average’ small farm.

This coincidence of normal farm size and family size is not an accident, but essentially represents multi-generational family units occupying the smallest possible farms which could support them. The pressures that produce this result are not hard to grasp: families with multiple children and a farm large enough to split between them might do so, while families without enough land to split are likely to cluster around the farm they have. Pre-modern societies typically have only limited opportunities for wage labor (which are often lower status and worse in conditions than peasant farming!), so if the extended family unit can cluster on a single farm too small to split up, it will (with exception for the occasional adventurous type who sets off for high-risk occupations like soldier or bandit).

Now to be clear that doesn’t mean the farm sizes are uniform, because they aren’t. There is tremendous variation and obviously the difference between a 10 acre small farm and a 5 acre small farm is half of the farm. Moreover, in most of the communities you will have significant gaps between the poor peasants (whose farms are often very small, even by these measures), the average peasant farmer, and ‘rich peasants’ who might have a somewhat (but often not massively so) larger farm and access to more farming capital (particularly draft animals). We’ll deal with the truly big farmers – the landholding aristocrats and gentry – next week. Nevertheless, what I want to stress is that these fairly small – 3-8 acres of so – farms with an extended family unit on it make up the vast majority of farming households and most of the rural population, even if they do not control most of the land (for instance in that Languedoc village, more than half of the land was held by households with more than 20 setérée a piece, so a handful of those ‘rich peasants’ with larger accumulations effectively dominated the village’s landholding; again, we’ll talk about how a larger farm might differ next week).

This is our workforce and we’re going to spend this entire essay talking about them. Why? Because these folks – these farmers – make up the majority of the population of basically all agrarian societies in the pre-modern period. And when I say ‘the majority’ I mean the vast majority, on the order of 80-90% in many cases (I am including in that number non-free agricultural workers, who we’ll discuss more next time).

There is a second thing to note here with our fairly large families on fairly small farms: these farmers are inefficiently distributed as units of labor. Exactly how you estimate things vary, but as a ballpark figure, a household with two adult males could cultivate close to 20 acres of land (assuming the women and children of the household assisted with the high labor demand period, which is the harvest) – but they are likely to be on a farm a quarter of that size. Now as we’ll get to later in the series, there are still ways for them to use that surplus labor! But as an economic unit, the problem is that they have too many mouths and not enough land – for maximum efficiency, they ought to stretch the same number of people over more land.

Of course our farmers don’t care about maximum efficiency (because that means for maximum efficiency of people who aren’t the farmers eating the surplus). They care about marrying, having families, raising children, keeping friends, staying close to loved ones and so on. Farmers, after all, are people, not mere tools of agricultural production (we will talk about non-free farmers next time) and so they do not serve their farmers, their farms serve the needs of their families.

(I feel the need to note as an aside that in this series we’ll be very focused on these families as units of agricultural production, but that isn’t the whole of their output. In most cases, the majority of the agricultural labor in these households seems to have been done by men, with women coming into the fields mostly only at the periods of highest labor need (planting, harvest) or during periods of labor shortage (war, for instance). That is not to say the women are idle! They are not! In most cases, they are engaged with other essential household tasks, particularly household textile production, a topic that will get its own series a little later down the line. So if you see less of our female peasants than you might like, worry not – we are going to come back to them!)

The Farming Cycle

As you might imagine, time in agriculture is governed by the seasons. Crops must be planted at particular times, harvested at particular times. In most ancient societies, the keeping of the calendar was a religious obligation, a job for educated priests (either a professional priestly class as in the Near East, or local notables serving as amateurs, as in Greece and Rome).

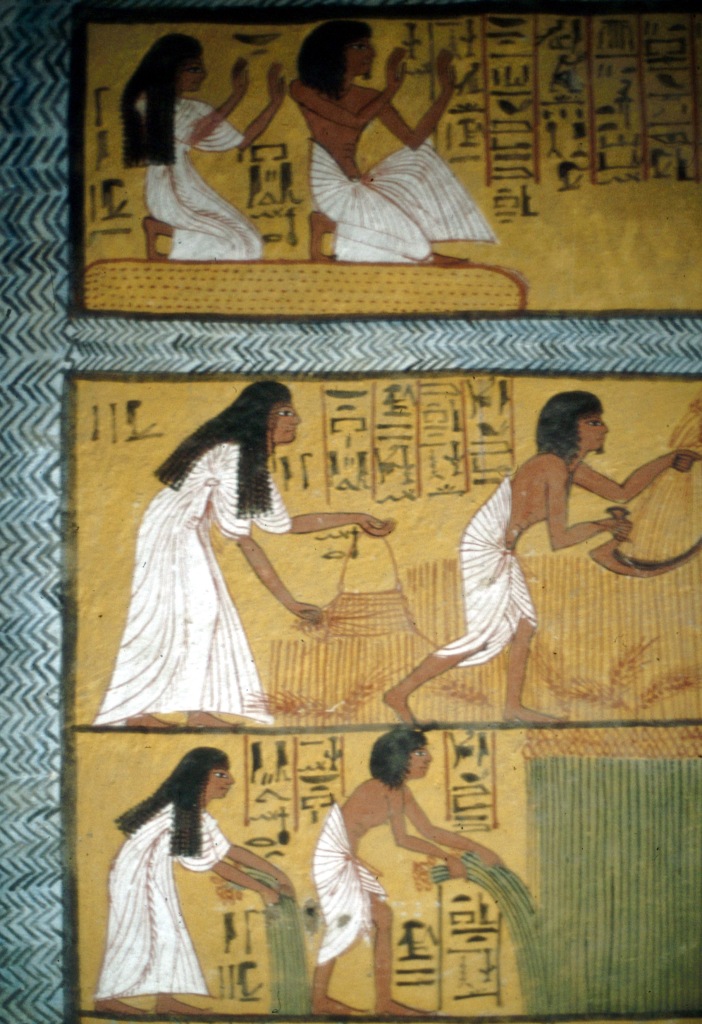

The seasonal patterns vary a bit depending on the conditions and the sort of wheat being sown. In much of the Mediterranean, where the main concern was preserving a full year’s moisture for the crop, planting was done in autumn (November or October) and the crop was harvested in early summer (typically July or August). In contrast, the Han agricultural calendar for wheat planted in the spring, weeded over the summer and harvested in fall. The Romans generally kept to the autumn-planting schedule, except our sources note that on land which was rich enough (and wet enough) to be continuously cropped year after year (without a fallow), the crop was sown in spring; this might also be done in desperation if the autumn crop had failed. In Egypt, sowing was done as the Nile’s flood waters subsided at the beginning of Peret (in January), with the harvest taking place in Shemu (summer or early fall).

(As an aside on the seasons: we think in terms of four seasons, but many Mediterranean peoples thought in terms of three, presumably because Mediterranean winters are so mild. Thus the Greeks have three goddesses of the seasons initially, the Horae (spring, summer and fall) and Demeter’s grief divides the year into thirds not fourths in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter. In ancient Egypt, there were three seasons: Akhet (Flood); Peret (Emergence [of fertile lands as the waters recede]) and Shemu (Low Water). The perception of the seasons depended on local climate and local cycles of agriculture.)

Note how the grain is rather taller than our modern varieties of modern dwarf wheat. Regular wheats can collapse when they grow tall under the influence of fertilizer and waste a lot of those nutrients getting tall (to compete for sunlight), so dwarf wheats are mostly used today for their thicker, more resilient stalks and greater efficiency.

This brings us to the most fundamental fact of rural life in the pre-modern world: the grain is harvested once a year, but the family eats every day. Of course that means the grain must be stored and only slowly consumed over the entire year (with some left over to be used as seed-grain in the following planting). That creates the first cycle in agricultural life: after the harvest, food is generally plentiful and prices for it are low (we’ll deal with the impact this has on trade and markets a little later). As the year goes on, food becomes scarcer and the prices for it rise as each family ‘eats down’ their stockpile.

That has more than just economic impacts because the family unit becomes more vulnerable as that food stockpile dwindles. Malnutrition brings on a host of other threats: elevated risk of death from injury or disease most notably. Repeated malnutrition also has devastating long-term effects on young children (a point we’ll come back to). Consequently, we see seasonal mortality patterns in agricultural communities which tend to follow harvest cycles; when the harvest is poor, the family starts to run low on food before the next harvest, which leads to rationing the remaining food, which leads to malnutrition. That malnutrition is not evenly distributed though: the working age adults need to be strong enough to bring in the next harvest when it comes (or to be doing additional non-farming labor to supplement the family), so the short rations are going to go to the children and the elderly. Which in turn means that ‘lean’ years are marked by increased mortality especially among the children and the elderly, the former of which is how the rural population ‘regulates’ to its food production in the absence of modern birth control (but, as an aside: this doesn’t lead to pure Malthusian dynamics – a lot more influences the food production ceiling than just available land. You can have low-equilibrium or high-equilibrium systems, especially when looking at the availability of certain sorts of farming capital or access to trade at distance. I cannot stress this enough: Malthus was wrong; yes, interestingly, usefully wrong – but still wrong. The big plagues sometimes pointed to as evidence of Malthusian crises have as much if not more to do with rising trade interconnectedness than declining nutritional standards). This creates yearly cycles of plenty and vulnerability; we’ll talk about the strategies these fellows employ to avoid that problem in just a moment.

Next to that little cycle, we also have a ‘big’ cycle of generations. The ratio of labor-to-food-requirements varies as generations are born, age and die; it isn’t constant. The family is at its peak labor effectiveness at the point when the youngest generation is physically mature but hasn’t yet begun having children (the exact age-range there is going to vary by nuptial patterns, see below) and at its most vulnerable when the youngest generation is immature. By way of example, let’s imagine a family (I’m going to use Roman names because they make gender very clear, but this is a completely made-up family): we have Gaius (M, 45), his wife, Cornelia (39, F), his mother Tullia (64, F) and their children Gaius (21, M), Secundus (19, M), Julia1 (16, F) and Julia2 (14, F). That family has three male laborers, three female laborers (Tullia being in her twilight years, we don’t count), all effectively adults in that sense, against 7 mouths to feed. But let’s fast-forward fifteen years. Gaius is now 60 and slowing down, Cornelia is 54; Tullia, we may assume has passed. But Gaius now 36 is married to Clodia (20, F; welcome to Roman marriage patterns), with two children Gaius (3, M) and Julia3 (1, F); Julia1 and Julia2 are married and now in different households and Secundus, recognizing that the family’s financial situation is never going to allow him to marry and set up a household has left for the Big City. So we now have the labor of two women and a man-and-a-half (since Gaius the Elder is quite old) against six mouths and the situation is likely to get worse in the following years as Gaius-the-Younger and Clodia have more children and Gaius-the-Elder gets older. The point of all of this is to note that just as risk and vulnerability peak and subside on a yearly basis in cycles, they also do this on a generational basis in cycles.

(An aside: the exact structure of these generational patterns follow on marriage patterns which differ somewhat culture to culture. In just about every subsistence farming culture I’ve seen, women marry young (by modern standards) often in their mid-to-late teens, or early twenties; that doesn’t vary much (marriage ages tend to be younger, paradoxically, for wealthier people in these societies, by the by). But marriage-ages for men vary quite a lot, from societies where men’s age at first marriage is in the early 20s to societies like Roman and Greece where it is in the late 20s to mid-thirties. At Rome during the Republic, the expectation seems to have been that a Roman man would complete the bulk of their military service – in their twenties and possibly early thirties – before starting a household; something with implications for Roman household vulnerability. Check out Rosenstein, op. cit. on this).

On top of these cycles of vulnerability, you have truly unpredictable risk. Crops can fail in so many ways. In areas without irrigated rivers, a dry spell at the wrong time is enough; for places with rivers, flooding becomes a concern because the fields have to be set close to the water-table. Pests and crop blights are also a potential risk factor, as of course is conflict.

So instead of imagining a farm with a ‘standard’ yield, imagine a farm with a standard grain consumption. Most years, the farm’s production (bolstered by other activities like sharecropping that we’ll talk about later) exceed that consumption, with the remainder being surplus available for sale, trade or as gifts to neighbors and friends. Some years, the farm’s production falls short, creating that shortfall. Meanwhile families tend to grow to the size the farm can support, rather than to the labor needs the farm has, which tends to mean too many hands (and mouths) and not enough land. Which in turn causes the family to ride a line of fairly high risk in many cases.

All of this is to stress that these farmers are looking to manage risk through cycles of vulnerability. Which leads to:

Risk Control

I led in with all of that risk and vulnerability because without it just about nothing these farmers do makes a lot of sense; once you understand that they are managing risk, everything falls into place.

Most modern folks think in terms of profit maximization; we take for granted that we will still be alive tomorrow and instead ask how we can maximize how much money we have then (this is, admittedly, a lot less true for the least fortunate among us). We thus tend to favor efficient systems, even if they are vulnerable. From this perspective, ancient farmers – as we’ll see – look very silly, but this is a trap, albeit one that even some very august ancient scholars have fallen into. These are not irrational, unthinking people; they are poor, not stupid – those are not the same things.

But because these households wobble on the edge of disaster continually, that changes the calculus. These small subsistence farmers generally seek to minimize risk, rather than maximize profits. After all, improving yields by 5% doesn’t mean much if everyone starves to death in the third year because of a tail-risk that wasn’t mitigated. Moreover, for most of these farmers, working harder and farming more generally doesn’t offer a route out of the small farming class – these societies typically lack that kind of mobility (and also generally lack the massive wealth-creation potential of industrial power which powers that kind of mobility). Consequently, there is little gain to taking risks and much to lose. So as we’ll see, these farmers generally sacrifice efficiency for greater margins of safety, every time.

Avoiding risk for these farmers comes in two main forms: there are strategies to reduce the risk of failure within the annual cycle and then strategies to prepare for failure by ‘banking’ the gains of a good cycle against the losses of a bad cycle.

Let’s start with the first sort of risk mitigation: reducing the risk of failure. We can actually detect a lot of these strategies by looking for deviations in farming patterns from obvious efficiency. Modern farms are built for efficiency – they typically focus on a single major crop (whatever brings the best returns for the land and market situation) because focusing on a single crop lets you maximize the value of equipment and minimize other costs. They rely on other businesses to provide everything else. Such farms tend to be geographically concentrated – all the fields together – to minimize transit time.

Subsistence farmers generally do not do this. Remember, the goal is not to maximize profit, but to avoid family destruction through starvation. If you only farm one crop (the ‘best’ one) and you get too little rain or too much, or the temperature is wrong – that crop fails and the family starves. But if you farm several different crops, that mitigates the risk of any particular crop failing due to climate conditions, or blight (for the Romans, the standard combination seems to have been a mix of wheat, barley and beans, often with grapes or olives besides; there might also be a small garden space. Orchards might double as grazing-space for a small herd of animals, like pigs). By switching up crops like this and farming a bit of everything, the family is less profitable (and less engaged with markets, more on that in a bit), but much safer because the climate conditions that cause one crop to fail may not impact the others. A good example is actually wheat and barley – wheat is more nutritious and more valuable, but barley is more resistant to bad weather and dry-spells; if the rains don’t come, the wheat might be devastated, but the barley should make it and the family survives. On the flip side, if it rains too much, well the barley is likely to be on high-ground (because it likes the drier ground up there anyway) and so survives; that’d make for a hard year for the family, but a survivable one.

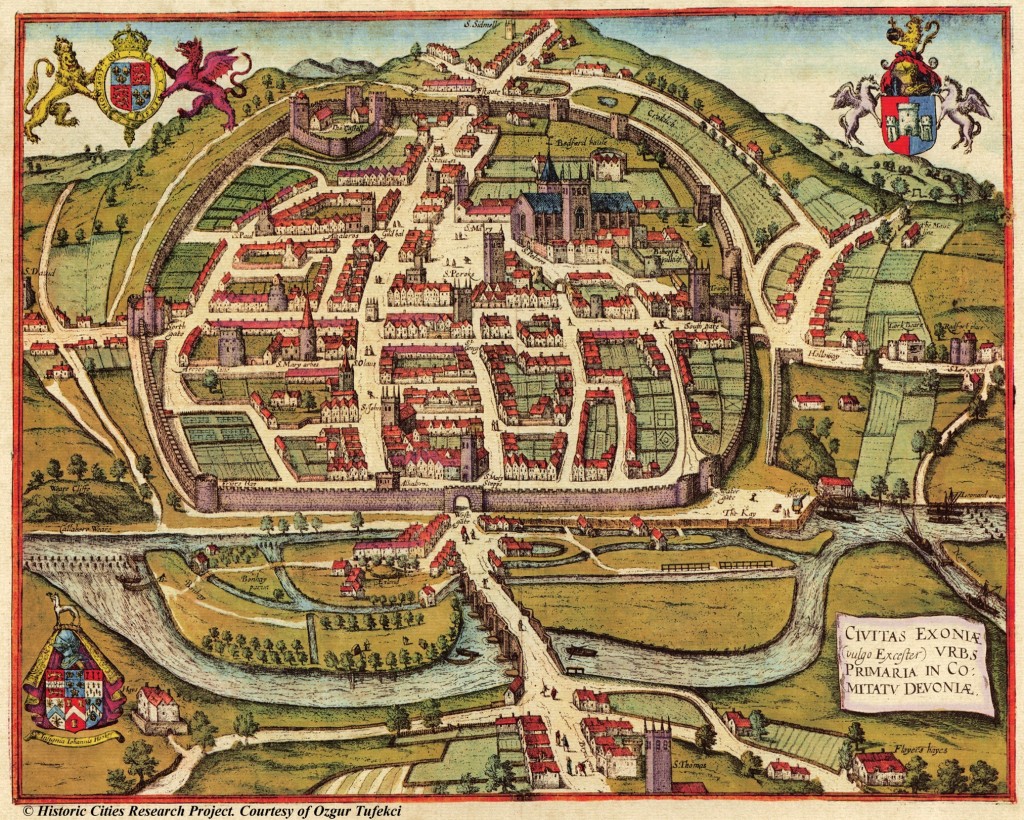

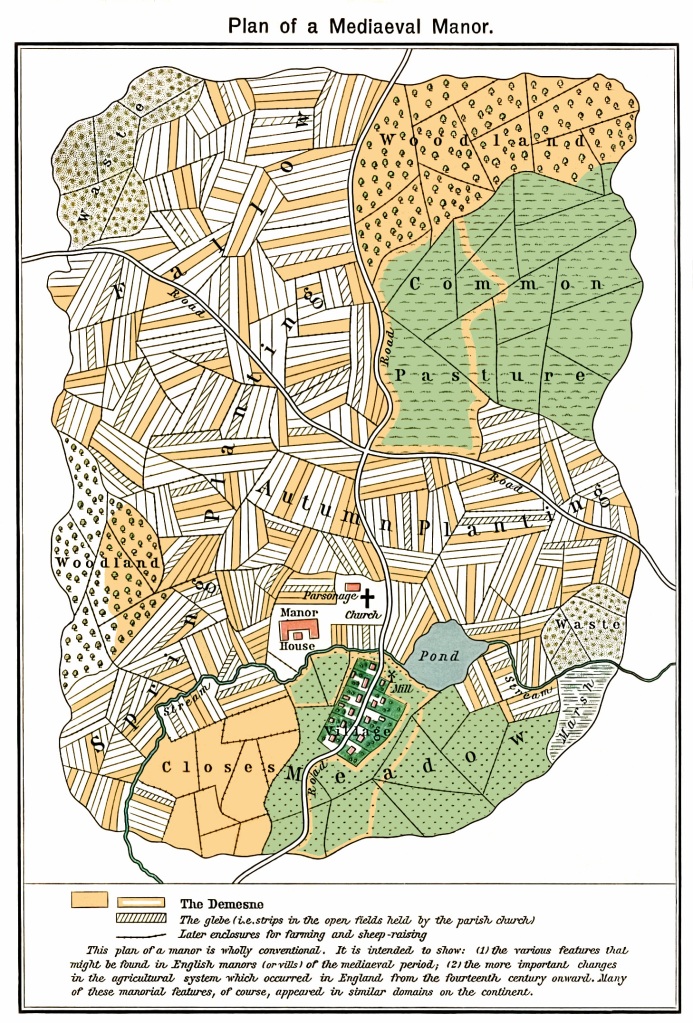

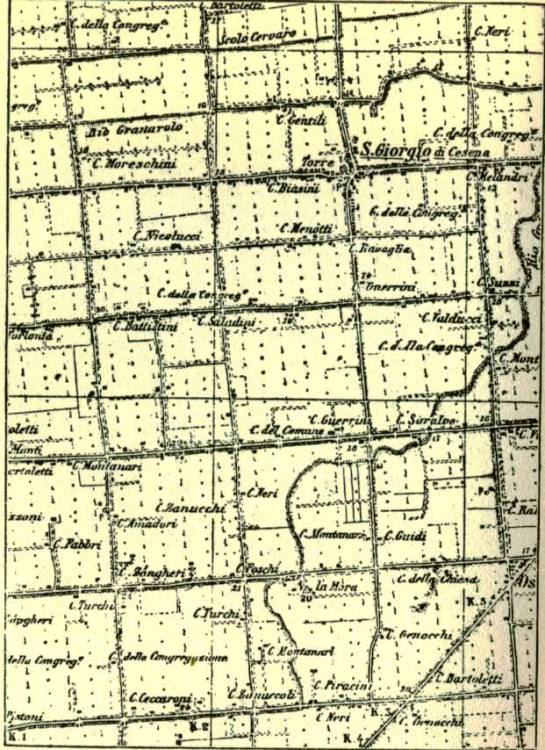

Likewise – as that example implies – our small farmers want to spread out their plots. And indeed, when you look at land-use maps of villages of subsistence farmers, what you often find is that each household farms many small plots which are geographically distributed (this is somewhat less true of the Romans, by the by). Farming, especially in the Mediterranean (but more generally as well) is very much a matter of micro-climates, especially when it comes to rainfall and moisture conditions (something that is less true on the vast flat of the American Great Plains, by the by). It is frequently the case that this side of the hill is dry while that side of the hill gets plenty of rain in a year and so on. Consequently, spreading plots out so that each family has say, a little bit of the valley, a little bit of the flat ground, a little bit of the hilly area, and so on shields each family from catastrophe is one of those micro-climates should completely fail (say, the valley floods, or the rain doesn’t fall and the hills are too dry for anything to grow).

All of this serves to make our farmers less efficient. More travel time to spread out plots means less labor time (and as we’ll see next week, labor is a key input, even on small farms), while splitting between different crops squanders some of any comparative advantage a region may have in any particular crop and prevents efficiencies of scale within the household besides. But, the attentive reader may ask, why not compensate against risk by farming efficiently and then banking the good years to cover the bad years?

Banking the Yields

Of course our pre-modern subsistence farmers do not have access to modern banking systems or really any banking systems. Now debt-lenders exist in many of these societies – quite a lot of them. We even see joint-venture capitalized lending operations (read: banks) in more economically complex ancient societies. But what you do not have is a savings account, which is what our farmers could really use: a place to safely store the value of the good years, against the threat of the bad years (although, for reasons we’ll get to in a moment, money itself is not a perfect vehicle for this). And saving accounts like that simply do not exist for our farmers. More to the point, a government that can mint or print money and is willing to vouchsafe savings accounts does not exist – modern banking didn’t help poor farmers in the crash of 1929 because all of their banks went under (thus, in the United States, the later institution of the FDIC). So savings accounts don’t exist and even if they did exist they wouldn’t work for our farmers who couldn’t count on the bank to still be solvent in a bad year.

Why not store the yield itself? The short answer is that our farmers are doing this, to a degree, all the time. After all, the harvest comes in once a year, but must be eaten all year, which demands storage; moreover, some of the harvest must be kept for seed in the following year. But in terms of banking yields against future bad harvests, we run into storage problems. The first is storage space. Grain is a bulk commodity, after all. In my own research, I’ve done some calculations working out the food requirements for a Roman family of five to around 200 modii (a Roman unit of grain measurement by volume) of grain, which comes to 1,746 liters (1.74 cubic meters); once you’ve divided that into containers and put it on shelves, it’s enough to fill a small cellar. Doubling that storage capacity is a significant capital improvement – of course granaries existed in the ancient world, but they tended to serve communities and weren’t designed for storage over multiple years.

But while the storage problems could be surmounted with difficulty, spoilage problems largely cannot. Estimating how long grain can be stored is tricky – much depends on conditions and the rate of loss (called spoilage) is not linear, but rather accelerates over time. In practice, for the first year of storage, assuming the grain is stored in a cool, dry space not exposed to sunlight or accessible to other animals, the spoilage rate is acceptably low. But the longer that grain is stored the more pests and the spoilage process multiplies and accelerates. That puts a cap on how long the grain can be stored under the sort of conditions a pre-modern society could provide; much beyond a year, the usability of the grain was at best a question mark. Attempting to store that much of a surplus over multiple years would be a wasteful non-starter.

Ok, so why not sell the grain and store something less perishable, like money? Sure, you can’t put it in a bank, but you can just keep it. And indeed, our ancients do this – remember the Penates, who guard the family’s storeroom (fun aside: the actual box or basket the family’s valuables were kept in was known by the Romans as the fiscus from where we get our word fiscal; in the first century it came to mean a part of the imperial treasury). But money shares a problem with grain: it can be stolen. While we have mostly focused on the threat of bad harvests, that’s not the only risk farmers are trying to insulate against. Villages might be vulnerable to bandits. Little different, armies moving over the countryside are likely to seize whatever grain (or funds!) they need. And subsistence farmers are generally powerless before state extraction too: money can be taxed – often extortionately so. In short, the very portability of money is a potential detriment here.

Money also has one problem that grain does not, which is bound up in the way prices work in agricultural societies. The risks the farming family most wants to insulate themselves against, whether caused by war or harvest failure, are risks that involve a contracting food supply. The thing is, as the food supply contracts, the price of food rises and the ability to buy it with money shrinks (often accelerated by food hoarding by the wealthy cities, which are often in a position to back that up with force as the administrative centers of states). Consequently, for the family, money is likely to become useless the moment it is needed most. So while keeping some cash around against an emergency (or simply for market transactions – more on that later) might be a good idea, keeping nearly a year’s worth of expenses to make it through a bad harvest was not practical.

So how is a farmer to use good years as a way to cushion bad years?

Banqueting the Yields

The answer was often to invest in relationships rather than in money. There are two key categories here: horizontal relationships (with other subsistence farmers) and vertical relationships (with wealthy large landowners). We’ll finish out this section dealing with the former and turn to the many impacts of the large landowners next week.

The most immediate of these are the horizontal relationships: friends, family, marriage ties and neighbors. While some high-risk disasters are likely to strike an entire village at once (like a large raid or a general drought), most of the disasters that might befall one farming family (an essential worker being conscripted, harvest failure, robbery and so on) would just strike that one household. So farmers tended to build these reciprocal relationships with each other: I help you when things are bad for you, so you help me when things are bad for me. But those relationships don’t stop merely when there is a disaster, because – for the relationship to work – both parties need to spend the good times signalling their commitment to the relationship, so that they can trust that the social safety net will be there when they need it.

So what do our farmers do during a good harvest to prepare for a bad one? They banquet their neighbors, contribute to village festivals, marry off their sons and daughters with the best dowry they can manage, and try to pay back any favors they called in from friends recently. I stress these not merely because they are survival strategies (though they are) but because these sorts of activities end up (along with market days and the seasonal cycles) defining a great deal of life in these villages. But these events also built that social capital which can be ‘cashed out’ in an emergency. And they are a good survival strategy. Grain rots and money can be stolen, but your neighbor is far likelier to still be your neighbor in a year, especially because these relationships are (if maintained) almost always heritable and apply to entire households rather than individuals, making them able to endure deaths and the cycles of generations.

So this strategy of banqueting your neighbor in the good times is essential for our subsistence farmer to survive the unpredictability of agricultural life. But it has some other impacts too. These networks of relationships can – and do – absolutely save these households in a crisis, but they also diffuse capital. This phenomenon is not, by the way, restricted to ancient farmers, but is a well documented pattern among individuals with limited access to financial capital in modern societies. We’ll deal more with farming capital next week, but I want to note this impact now, because it will help explain some things then.

Conclusions

Now there is a lot to unpack here and so much more we could go into. We’re going to deal with the mechanics of farming and how the Big Farmers – the large estate holders – fit in later in this series (and don’t worry, that will bring us back to our subsistence farmers, who are really the stars of our show here). But I want to close out this section by noting one major non-obvious effect of all of this.

There is a ton of food in this countryside (nearly everyone is producing it) but hardly any surplus. There are a number of factors that lead to this outcome. First, our small farmers aren’t producing for maximum efficiency, but for minimum risk (spread out fields, multi-crop strategies) which lowers total production compared to monocropping the most calorie or market-efficient crop. Second, our farming families – lacking effective birth control – tend to grow to the size their farm will support. If the option is available, they may then fission (or members may go to cities in search of jobs), but they’re not likely to do this until the family is decidedly too large for the farm. People like family and families tend to stick together, after all (and leaving that carefully constructed safety net of social capital without much in the way of financial resources or legal protection is terrifying, as you may imagine). Finally, when our farmers do have a surplus, rather than investing it into capital improvements, they’re likely to rapidly spend it on restoring their social capital safety net by gifting it to their neighbors in the forms of marriage dowries, banquets, bailing out a friend in trouble and so on.

And finally, just to point out the obvious: farming labor is hard. It is back-breaking, uncomfortable stuff. And for these small farmers for whom upward social mobility is often very literally impossible (often prevented as a matter of law and custom, but also – as we’ll get to next week and after – made very difficult by economic and social structures), there isn’t a whole lot of incentive to aim higher than, as Paul Erdkamp puts it, “subsistence – and a little bit more.” Exactly how much more is subject to a lot of social variation though. We’ve met one cause already: the expected cost of maintaining those key social relations is going to be layered on top of subsistence and if that is higher, our farmers will aim higher to reach it in order to remain ‘respectable.’ That said, there is still an upper limit to this and our farmers aren’t likely to work past it. This isn’t because they are ‘lazy’ – the ‘lazy peasant’ (or poor worker generally) is a standard hypocrisy of the literature of the leisured aristocratic class towards poor farmers, today and in the past – but because they have priorities which are simply not served by labor maximization. For these families, the marginal value of working harder to produce a little bit more which they cannot eat and will likely be taken from them anyway is minimal; they focus on the goals they have. Why should these peasants break their backs so that leisured aristocrats can have more economic activity to tax? Remember: these people were poor, not stupid – they are not the same thing.

(You may note so far I have been blurring the line between money that can be spent and agriculture surplus which is not money. Don’t worry – we’ll start drawing that line with more distinction when we get to market interactions. For right now, a pile of wheat and a (much, much smaller) pile of shiny coins represent much the same thing: both accumulated value through labor but also a fungible commodity which can be spent.)

On the one hand, all of this makes the peasantry really resilient to all sorts of shocks, as they are already minimizing the impact of risk and then their social networks naturally tend to redistribute survival resources to heavily impacted households. On the other hand, imagine the situation from the perspective of a tax collector or a merchant looking to acquire surplus food from the countryside (the former by force, the latter by trade). There simply isn’t much surplus to acquire. Now we’ll see, when we get to market interaction, all of the ways that non-farmers, particularly that tax collector, use to try not just to extract surplus from these farmers but to try to force them to produce a surplus that can be extracted, but for now there isn’t much.

Consequently even in cases where farming yields (that is, seed-in to food-out or yield-by-land) seem high enough to produce a robust surplus, the very structure of the households of subsistence farmers will tend to consume and redistribute that surplus, trapping it in the countryside, leaving only a tiny fraction (something like 10% is a normal back-of-the-envelope estimate) for the cities of non-farmers.

We’ll see that problem compound a bit when we look at the distribution of farming capital – valuable things like land, animals, equipment and yes – manure. Next week, we’ll look at the role big farms play in the countryside.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2ZVKiwc

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.