A Crash Course on Advanced DLIs

Atari 8-bit Display List Interrupts: An Advanced Tutorial

Revision 1, updated 3 Dec 2019

This is a tutorial on advanced Display List Interrupts (DLIs) for the Atari 8-bit series of computers. In a nutshell, DLIs provide a way to notify your program when a particular scan line is reached, allowing you to make changes mid-screen.

DLIs are an advanced programming technique in the sense that they require knowledge of 6502 assembly language, so this tutorial is going to assume that you are comfortable with that. All the examples here are assembled using the MAC/65-compatible assembler ATasm (and more specifically to this tutorial, the version built-in to Omnivore).

Before diving into DLIs, it is helpful to understand that they are very accurately named: Display List Interrupts literally interrupt the display list – they cause an event that is processed by your program while the ANTIC is drawing the screen. So it is necessary to understand what display lists are before understanding what it means to interrupt one.

See also

Here are some resources for learning more about display list interrupts:

A Crash Course on Displays

A TV screen is drawn by an electron beam tracing a path starting above the visible area, and drawing successive horizontal lines as the beam moves down the screen. Each line is drawn from left-to-right (as you look at the TV screen) and when it reaches the right hand side of the screen, the horizontal retrace starts where the beam is turned off and moved down to the next scan line below whereupon the beam is turned back on and the next line draws. When the full frame has been drawn, the beam is turned off again and the vertical retrace starts (starting the vertical blank interval). Once the beam is repositioned to the top leftmost position, the vertical blank interval ends, the beam is turned back on, and the next frame is started.

On NTSC systems, the Atari draws 262 scan lines per frame, 60 times per second. On PAL systems it draws 312 scan lines per frame, 50 times per second. In either system, it draws scan lines from the top down, and left to right within a scan line.

This simplified description is the mental model we will use to describe the video drawing process.

How Interlacing Works (With Some Hand Waving) and Why We Ignore It

Real TVs are interlaced with 525 scan lines for NTSC and 625 for PAL. Because of reasons, the NTSC vertical refresh interval is not exactly the whole number of 60Hz either, it’s 60/1001 Hz or 59.94Hz. PAL refresh rate is apparently exactly 50Hz.

Every refresh interval, the electron beam draws one field, starting at the top left and drawing every other scan line. When it reaches the bottom, the vertical retrace starts, but this time it positions the electron beam at the first missing scan line. Then it draws the next field, again skipping every other scan line but this time filling in the scan lines it missed.

This drawing is a simplification, seeming to show that there are 524 scan lines. In reality, and there are 525 and each field actually draws 262 and one half scan lines (and not 262 on one field and 263 on another), but this is all very complicated and not necessary for our purposes. However, at the risk of further complicating matters, the Atari produces 262 scan lines for the even field and 262 scan lines for the odd field. In the situation where the Atari is producing an image that is not changing as time goes on, like the computer is sitting at the BASIC language READY prompt and you aren’t typing anything, the scan lines produced for the even field will be exactly the same as the scan lines produced for the odd field.

Practically speaking, you do not need to care that the screen is interlaced with 525 scan lines (for NTSC). Our mental model will be as if the Atari is drawing to a non-interlaced screen with 262 scan lines and a frame rate of 59.94Hz. (For PAL, substitute 625, 312, and 50, respectively.)

How Color Works and There’s More Hand Waving, Isn’t There?

How TVs produce the colors that they display is very complicated and so far outside the scope of this tutorial that it might as well be magic. Suffice it to say that color happens.

On the Atari, a unit called the color clock is the smallest portion of a scan line that can be displayed with an arbitrary color. There are 228 color clocks per scan line, of which about 160 were typically visible on a cathode-ray TV display in the 1970s when the Atari was developed. This corresponds to the 160 pixel horizontal resolution of Antic Modes B through E in the standard width playfield. Antic Mode F (Graphics 8 in BASIC) has 320 addressable pixels, corresponding to half a color clock, and only artifacting color is available.

A Crash Course on Display Lists

ANTIC is the special coprocessor that handles screen drawing for the Atari computers. It is tightly coupled with the 6502 processor, and in fact can be thought of as being the driver of the 6502 because the ANTIC can halt the 6502 when needed. Since only one chip can read memory at any time, ANTIC needs to halt the 6502 when it needs access to memory, so this Direct Memory Access (DMA) can cause 6502 instructions to appear to take more cycles than documented in a 6502 reference. In fact, the amount of time ANTIC “steals” will depend on many factors: the graphics mode, player/missiles being used, playfield size, and more.

Since there are 228 color clocks and 114 machine cycles per scan line, this means that in one machine cycle, two color clocks are drawn on the screen. A typical machine instruction might take 5 machine cycles, so 10 color clocks could pass in the time to process a single instruction! This means we don’t have much time per scan line, so DLIs that attempt to change graphics in the middle of a line will have to be well optimized.

It also means the 6502 is too slow to draw the screen itself, and this is where ANTIC’s special “instruction set” comes in. You program the ANTIC coprocessor using a display list, and ANTIC takes care of building the screen scan line by scan line, without any more intervention from the 6502 code. (Unless you ask for intervention! And that’s what a DLI is.)

The display list is the special sequence of bytes that ANTIC interprets as a list of instruction. Each instruction causes ANTIC to draw a certain number of scan lines in a particular way. A DLI can be set on any ANTIC instruction.

ANTIC supports display lists that produce at most 240 scan lines (even on PAL systems where many more scan lines are available), and the vertical blank interval always starts after 248 scan lines. When drawing scan lines, ANTIC skips 8 scan lines at to top of the display, so the output from the display list starts at the 9th scan line. A standard display list starts with 24 blank lines and 192 scan lines of display data, meaning that the TV will see 32 blank lines (the 8 automatically skipped plus the 24 in a standard display list) followed by 192 scan lines of display, then 24 blank lines, and finally the vertical blank that consumes the remaining 14 scan lines on NTSC (or 64 on PAL).

Display List Instruction Set

An ANTIC display list instruction consists of 1 byte with an optional 2 byte address. There are 3 types of instructions: blank lines, graphics modes, and jump instructions. Instructions are encoded into the byte using a bitmask where low 4 bits encode the graphics mode or feature and the high 4 bits encode the flags that affect that instruction:

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

DLI

LMS

VSCROLL

HSCROLL

Mode

The 4 flags are:

DLI (

$80): enable a display list interrupt when processing this instructionLMS (

$40): trigger a Load Memory Scan, changing where ANTIC looks for screen data, and requires an additional 2 byte address immediately following this instruction byte.VSCROLL (

$20): enable vertical scrolling for this mode lineHSCROLL (

$10): enable horizontal scrolling for this mode line

The 14 available graphics modes are encoded into low 4 bits using values as shown in this table:

|

Mode |

Decimal |

BASIC Mode |

Description |

Scan Lines |

Type |

Colors |

|

2 |

02 |

0 |

40 x 24 |

8 |

text |

2 |

|

3 |

03 |

n/a |

40 x 19 |

10 |

text |

2 |

|

4 |

04 |

n/a |

40 x 24 |

8 |

text |

4 |

|

5 |

05 |

n/a |

40 x 12 |

16 |

text |

4 |

|

6 |

06 |

1 |

20 x 24 |

8 |

text |

5 |

|

7 |

07 |

2 |

20 x 12 |

16 |

text |

5 |

|

8 |

08 |

3 |

40 x 24 |

8 |

bitmap |

4 |

|

9 |

09 |

4 |

80 x 48 |

4 |

bitmap |

2 |

|

A |

10 |

5 |

80 x 48 |

4 |

bitmap |

4 |

|

B |

11 |

6 |

160 x 96 |

2 |

bitmap |

2 |

|

C |

12 |

n/a |

160 x 192 |

1 |

bitmap |

2 |

|

D |

13 |

7 |

160 x 96 |

2 |

bitmap |

4 |

|

E |

14 |

n/a |

160 x 192 |

1 |

bitmap |

4 |

|

F |

15 |

8 |

320 x 192 |

1 |

bitmap* |

2 |

*mode F is also used as the basis for the GTIA modes (BASIC Graphics modes 9, 10, & 11), but this is a topic outside the scope of this tutorial.

Blank lines are encoded as a mode value of zero, the bits 6, 5, and 4 taking the meaning of the number of blank lines rather than LMS, VSCROLL, and HSCROLL. Note that the DLI bit is still available on blank lines, as bit 7 is not co-opted by the blank line instruction.

|

Hex |

Decimal |

Blank Lines |

|

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

10 |

16 |

2 |

|

20 |

32 |

3 |

|

30 |

48 |

4 |

|

40 |

64 |

5 |

|

50 |

80 |

6 |

|

60 |

96 |

7 |

|

70 |

112 |

8 |

Jumps provide the capability to split a display list into multiple parts in different memory locations. They are encoded using a mode value of one, and require an additional 2 byte address where ANTIC will look for the next display list instruction. If bit 6 is also set, it becomes the Jump and wait for Vertical Blank (JVB) instruction, which is how ANTIC knows that the display list is finished. The DLI bit may also be set on a jump instruction, but if set on the JVB instruction it triggers a DLI on every scan line from there until the vertical blank starts on the 249th scan line.

Note

Apart from the $41 JVB instruction, splitting display lists using other jumps like the $01 instruction is not common. It has a side-effect of producing a single blank line in the display list.

The typical method to change the currently active display list is to change the address stored at SDLSTL (in low byte/high byte format in addresses $230 and $231). At the next vertical blank, the hardware display list at DLISTL ($d402 and $d403) will be updated with the values stored here and the screen drawing will commence using the new display list.

See also

More resources about display lists are available:

A Sample Display List

Here is a display list that contains different text modes mixed in a single screen.

dlist .byte $70,$70,$70 ; 24 blank lines .byte $46,$00,$40 ; Mode 6 + LMS, setting screen memory to $4000 .byte 6 ; Mode 6 .byte $70 ; 8 blank lines .byte 7,7,7,7,7 ; 5 lines of Mode 7 .byte $70 ; 8 blank lines .byte 2 ; single line of Mode 2 .byte $70,$70,$70 ; 24 blank lines .byte 2,4 ; Mode 2 followed by mode 4 .byte $70 ; 8 blank lines .byte 2,5 ; Mode 2 followed by mode 5 .byte $41,<dlist,>dlist ; JVB, restart same display list on next frame

Cycle Stealing by ANTIC

The ANTIC coprocessor needs to access memory to perform its functions, and since the 6502 and ANTIC can’t both access at once, ANTIC will pause execution of the 6502 when it needs to read memory. It happens at specific points within the 114 cycles of each scan line, but where it happens (and how many times the 6502 gets paused during the scan line) depends on the graphics mode.

For overhead, ANTIC will typically steal 3 cycles to read the display list, 5 cycles if player/missile graphics are enabled, and 9 cycles for memory refreshing. Scrolling requires additional cycle stealing because ANTIC needs to fetch more memory.

Bitmapped modes (modes 8 - F) have cycles stolen corresponding to the number of bytes per line used in that mode. For example, mode E will use an additional 40 cycles, so in the context of writing a DLI for a game, the typical number of stolen cycles could be 57 out of the 114 cycles per scan line: 17 cycles for ANTIC overhead and 40 for the number of bytes per line.

Text modes require additional cycles over bitmapped graphics modes, because ANTIC must fetch the font glyphs in addition to its other work. The first scan line of a font mode is almost entirely used by ANTIC and only a small number of cycles is available to the 6502. For normal 40-byte wide playfields, the first line of ANTIC modes 2 through 5 will yield at most about 30 cycles and subsequent lines about 60 cycles per scan line.

About the worst-case scenario is one of the best modes for games: ANTIC mode 4. This text mode, combined with scrolling and player/missile graphics and can reduce the available cycles to fewer than 10 on the first line and about 50 on subsequent lines!

A Crash Course on Display List Interrupts

DLIs are non-maskable interrupts (NMIs), meaning they cannot be ignored. When an NMI occurs, the 6502 jumps to the address stored at $fffa, which points to an OS routine that checks the type of interrupt (either a DLI or a VBI) and vectors through the appropriate user vector. The NMI handler takes care of saving the processor status register and sets the interrupt flag, but does not save any processor registers. The user routine is responsible for saving any registers that it uses, restoring them when it is done using them, and must exit using the RTI instruction.

Display list interrupts are not enabled by default. To use a DLI, the address vector at VDLSLT ($200 and $201) must be set to your routine, and then they must be enabled through a write to NMIEN at $d40e.

Warning

You must set the address of your DLI before enabling them, otherwise the DLI could be called and use whatever address is stored at $200.

This initialization code can look like the following, where the constants NMIEN_VBI and NMIEN_DLI are defined as $40 and $80, respectively, in hardware.s in the sample repository. Since NMIEN also controls the vertical blank interrupt, you must make sure that the VBI enable flag is also set.

; load display list interrupt address lda #<dli sta VDSLST lda #>dli sta VDSLST+1 ; activate display list interrupt and vertical blank interrupt lda #NMIEN_DLI | NMIEN_VBI sta NMIEN

If your program has multiple DLIs, it may be necessary to set your DLIs in a vertical blank interrupt to guarantee that ANTIC will process them in the right order. Outside the VBI, your code could be running at an arbitrary scan line, perhaps between display list instructions that have their DLI bits set. In Yaron Nir’s tutorial a different technique is used, one not requiring a vertical blank interrupt but instead using the RTCLOK 3-byte zero page variable to instead infer that a VBI has just occurred. The last of the bytes, location $14, is incremented every vertical blank, so that technique is to wait until location $14 changes, then set NMIEN:

lda RTCLOK+2 ?loop cmp RTCLOK+2 ; will be equal until incremented in VB beq ?loop ; activate display list interrupt and vertical blank interrupt lda #NMIEN_DLI | NMIEN_VBI sta NMIEN

Hardware & Shadow Registers

The Atari is a memory-mapped system, where hardware devices like the ANTIC and GTIA chips are mapped to locations in memory and data is passed back and forth by reading or writing to specific addresses. They are usually either read-only or write-only, and many times an address is used for wildly different features depending on whether the address is read from or written to.

Some of these hardware locations also have shadow registers in low RAM (typically page 2) that are labeled as performing the same function as a hardware register, with two important differences.

First, they can be both read and written to, so (assuming you always use the shadow register to update the hardware register) it is possible to find out the current state of a hardware register by reading its shadow.

Second, the hardware register is only updated once every vertical blank by an operating system routine that copies the shadow value to its hardware counterpart. Note that it does not happen the other way around, so changing a hardware register does not update a shadow register.

The shadow registers are a convenience for development in higher level languages like BASIC where speed is not paramount. But code within a DLI must use hardware registers directly to affect change on a scan line.

The shadow registers can still be useful in DLI development, in that they will automatically reset the hardware registers to the values in the shadow registers every vertical blank. This can be used to reset features like graphics colors and the character set address for the top of the screen at the next frame.

Note

This only works if the operating system’s immediate vertical blank routine has not been replaced (i.e. you are only using the deferred vertical blank VVBLKD at $224 and haven’t replaced the immediate vertical blank rountine VVBLKI at $222).

Some hardware registers have no shadows, like player position and size, so your own code (in the deferred VBI or the final DLI) must reset these to their correct values for the top of the screen.

|

Shadow |

Hex |

Hardware |

Hex |

Description |

|

GPRIOR |

26f |

PRIOR |

d01b |

Player/playfield priority selection register |

|

PCOLR0 |

2c0 |

COLPM0 |

d012 |

Color of player/missile 0 |

|

PCOLR1 |

2c1 |

COLPM1 |

d013 |

Color of player/missile 1 |

|

PCOLR2 |

2c2 |

COLPM2 |

d014 |

Color of player/missile 2 |

|

PCOLR3 |

2c3 |

COLPM3 |

d015 |

Color of player/missile 3 |

|

COLOR0 |

2c4 |

COLPF0 |

d016 |

Color of playfield 0 |

|

COLOR1 |

2c5 |

COLPF1 |

d017 |

Color of playfield 1 |

|

COLOR2 |

2c6 |

COLPF2 |

d018 |

Color of playfield 2 |

|

COLOR3 |

2c7 |

COLPF3 |

d019 |

Color of playfield 3 |

|

COLOR4 |

2c8 |

COLBK |

d01a |

Background color |

|

CHACT |

2f3 |

CHACTL |

d401 |

Character mode (inverse, upside-down characters) |

|

CHBAS |

2f4 |

CHBASE |

d409 |

Character base (page number of font) |

A Simple Example

A common use of display lists is to change colors in the middle of the screen.

Here is our first display list interrupt:

dli pha ; only using A register, so save old value to the stack lda #$7a ; new background color sta COLBK ; store it in the hardware register pla ; restore the A register rti ; always end DLI with RTI!

This is all the code it takes to change the color of the background. The obvious effect is the flickering line in the background, which we will solve in the next section.

Examining the code shows the boilerplate discussed above where DLIs always end with the RTI instruction and any registers used must be saved before your code changes them, and restored upon exit.

The work performed in the interrupt is just two instructions: a load of a color value and a store where it puts it in the hardware register for the background color. Again, as noted above, hardware registers must be used in DLIs, not the shadow registers as shadow registers are ignored until the vertical blank.

A Simple Example with WSYNC

The Atari provides a way to sync with a scan line to avoid the flickering effect of the previous example.

The flickering is avoided by saving some value (any value, the bit pattern is not important) to the WSYNC memory location at $d40a. This causes the 6502 to stop processing instructions until the electron beam nears the end of the scan line, at which point the 6502 will resume executing instructions. Because the electron beam is usually off-screen at this point, it is safe to change color registers for at least the next several instructions without artifacts appearing on screen.

dli pha ; only using A register, so save old value to the stack lda #$7a ; new background color sta WSYNC ; any value saved to WSYNC will trigger the pause sta COLBK ; store it in the hardware register pla ; restore the A register rti ; always end DLI with RTI!

Note

WSYNC (wait for horizontal blank) usually restarts the 6502 on or about cycle 105 out of 114, but there are cases that can delay that. See the Altirra Hardware Reference Manual for more information.

A DLI Can Affect Many Scan Lines

DLIs can really be thought of as a way for your program to be told when a certain display list instruction is reached. Apart from the setup and teardown of the DLI subroutine itself and some timing limitations discussed in the next section, arbitrary amounts of code can be executed in a DLI.

Note

Author’s note: thinking that DLIs had to be short was a great source of confusion to me when trying to figure out how rainbow effects were generated. My thinking was that DLIs could only affect a single line, and for instance I could not figure out how to get a color change in the middle of a text mode. I don’t know why I thought that something bad would happen if a DLI went long, but I did.

This example shows how to have a single DLI affect multiple scan lines, even crossing into subsequent ANTIC mode 4 lines in the display list:

dli pha ; save A & X registers to stack txa pha ldx #16 ; make 16 color changes lda #$a ; initial color sta WSYNC ; first WSYNC gets us to start of scan line we want ?loop sta COLBK ; change background color clc adc #$11 ; change color value, luminance remains the same dex ; update iteration count sta WSYNC ; make it the color change last ... sta WSYNC ; for two scan lines bne ?loop ; sta doesn't affect flags so this still checks result of dex lda #$00 ; reset background color to black sta COLBK pla ; restore X & A registers from stack tax pla rti ; always end DLI with RTI!

It changes background colors 16 times, where each color change lasts 2 scan lines. So 32 scan lines means that it covers 4 display list entries of ANTIC mode 4.

A Crash Course on Display List Interrupts Getting Interrupted

DLIs can be interrupted by other DLIs

DLIs can be interrupted by the vertical blank

a DLI on a JVB instruction will cause interrupts on every scan line until the vertical blank

DLI Interrupting Another DLI

When a DLI is interrupted, its state is saved just as if a normal program was interrupted. The interrupting code is then executed, and upon its completion, the control returns to the DLI at the point where it left off. But at this point, due to the interrupting event, the restored DLI will be resumed some number of scan lines below where it was interrupted, likely resulting in unplanned behavior.

Here’s a similar DLI to the above, except it changes the luminance value instead of the color value to make the effect easier to see. It starts with a bright pink and gets dimmer down to a dark red after 32 scan lines:

dli pha ; save A & X registers to stack txa pha ldx #16 ; make 16 color changes lda #$5f ; initial bright pink color sta WSYNC ; first WSYNC gets us to start of scan line we want ?loop sta COLBK ; change background color sec sbc #1 ; make dimmer by decrementing luminance value dex ; update iteration count sta WSYNC ; make it the color change last ... sta WSYNC ; for two scan lines bne ?loop ; sta doesn't affect processor flags so we are still checking result of dex lda #$00 ; reset background color to black sta COLBK pla ; restore X & A registers from stack tax pla rti ; always end DLI with RTI!

But this time, the display list has two lines that have the DLI bit set:

dlist .byte $70,$70,$70 .byte $44,$00,$40 .byte $c4 ; first DLI triggered on last scan line .byte $44 .byte $c4 ; second DLI triggered on last scan line .byte $44,$44,$44,$44,$44,$44,$44,$44 .byte $44,$44,$44,$44,$44,$44,$44,$44 .byte $44,$44,$44,$44 .byte $41,<dlist,>dlist

Because the VDLSTL pointer is not changed, the same code will be called each time an interrupt occurs.

The first DLI hits and starts with a bright background color on the first scan line of the third line of text. But because this display list takes a long time, the second DLI on the 4th text line gets triggered before the first DLI has hit its RTI instruction. ANTIC interrupts the first DLI and starts the 2nd DLI anyway. This effect is visible in the 5th line of text: the background color is bright again.

But notice another artifact: the effect on the 5th line of text isn’t on its first scan line, but its second:

This is due to the fact that a WSYNC was called on the previous scan line, but the interrupt happened as well. The interrupt takes some cycles to begin, and by the time that happened and ANTIC stole all of its cycles to set up the text mode line, there weren’t enough cycles left for the first WSYNC in the DLI code to happen on the same scan line. This forces that WSYNC to happen on the next line, causing the delay and the appearance of a 3rd scan line of the same color before the second DLI starts its color cycling.

The second DLI completes and performs its RTI, but then it returns control to the first DLI, which is already halfway done with its color cycling. When it resumes control, it is in 9th line of text on the screen, so it has four more color changes before it hits its own RTI.

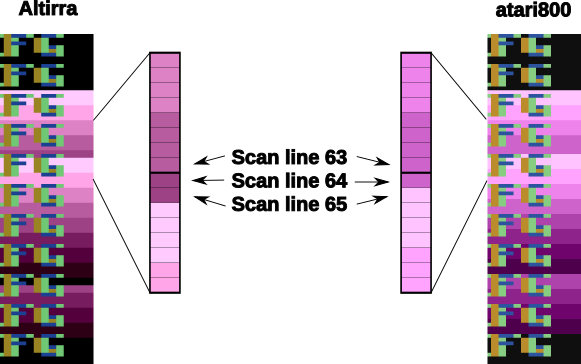

Emulator Differences

The DLI interrupting another DLI is clearly an edge case, and edge cases are always good stress tests for emulators. A difference is clearly visible below when comparing a zoomed in portion of the display generated by the Altirra emulator as compared to the atari800 emulator (standalone or as embedded in Omnivore, they are the same code and produce the same result):

Notice how Altirra gets the color from the first DLI for two scan lines, 64 and 65, before the correct color appears on scan line 66. The output from Altirra shows that the NMI doesn’t happen until between scan line 63 and 64. But clearly, the sta COLBK at scan line 63 is taking effect on scan line 64, because scan line 64 has the background color $57. It appears the store of $5f on scan line 65, started on cycle 1 of that line, isn’t actually executed until much, much later since the sec doesn’t begin until cycle 108. This puts that color change in the horizontal blank period of scan line 65, which would seem to explain why Altirra shows two scan lines with the background color from the first DLI.

This is the CPU history from the Altirra emulator:

60: 3 | A=58 X=09 Y=00 ( I C) | 3030: 8D 0A D4 STA WSYNC 60: 7 | A=58 X=09 Y=00 ( I C) | 3033: 8D 0A D4 STA WSYNC 60:108 | A=58 X=09 Y=00 ( I C) | 3036: D0 F1 BNE $3029 61:107 | A=58 X=09 Y=00 ( I C) | 3029: 8D 1A D0 L3029 STA COLBK 61:111 | A=58 X=09 Y=00 ( I C) | 302C: 38 SEC 61:113 | A=58 X=09 Y=00 ( I C) | 302D: E9 01 SBC #$01 62: 1 | A=57 X=09 Y=00 ( I C) | 302F: CA DEX 62: 3 | A=57 X=08 Y=00 ( I C) | 3030: 8D 0A D4 STA WSYNC 62: 7 | A=57 X=08 Y=00 ( I C) | 3033: 8D 0A D4 STA WSYNC 62:108 | A=57 X=08 Y=00 ( I C) | 3036: D0 F1 BNE $3029 63:107 | A=57 X=08 Y=00 ( I C) | 3029: 8D 1A D0 L3029 STA COLBK - NMI interrupt (DLI) 64: 5 | A=57 X=08 Y=00 ( I C) | E791: 2C 0F D4 LE791 BIT NMIST 64: 11 | A=57 X=08 Y=00 (N I C) | E794: 10 03 BPL $E799 64: 13 | A=57 X=08 Y=00 (N I C) | E796: 6C 00 02 JMP (VDSLST) 64: 19 | A=57 X=08 Y=00 (N I C) | 301F: 48 PHA 64:102 | A=57 X=08 Y=00 (N I C) | 3020: 8A TXA 64:104 | A=08 X=08 Y=00 ( I C) | 3021: 48 PHA 64:107 | A=08 X=08 Y=00 ( I C) | 3022: A2 10 LDX #$10 64:109 | A=08 X=10 Y=00 ( I C) | 3024: A9 5F LDA #$5F 64:111 | A=5F X=10 Y=00 ( I C) | 3026: 8D 0A D4 STA WSYNC 65: 1 | A=5F X=10 Y=00 ( I C) | 3029: 8D 1A D0 L3029 STA COLBK 65:108 | A=5F X=10 Y=00 ( I C) | 302C: 38 SEC 65:110 | A=5F X=10 Y=00 ( I C) | 302D: E9 01 SBC #$01 65:112 | A=5E X=10 Y=00 ( I C) | 302F: CA DEX 66: 0 | A=5E X=0F Y=00 ( I C) | 3030: 8D 0A D4 STA WSYNC 66: 4 | A=5E X=0F Y=00 ( I C) | 3033: 8D 0A D4 STA WSYNC 66:108 | A=5E X=0F Y=00 ( I C) | 3036: D0 F1 BNE $3029 67:107 | A=5E X=0F Y=00 ( I C) | 3029: 8D 1A D0 L3029 STA COLBK

The atari800 emulator hits the DLI two instructions earlier than Altirra, immediately after the two sta WSYNC commands (and therefore before the sta COLBK that causes Altirra to have a new color on scan line 64). In the atari800/Omnivore instruction history below:

<instruction history from omnivore goes here>

the DLI starts late on scan line 63 as (naively) expected and gets to the sta WSYNC early in scan line 64 while there is still time to hit the sta COLBK while still on scan line 64. This changes scan line 65 to be the correct background color for the second DLI.

Note

I’m not sure what’s going on with the differences in the WSYNC behavior between the two emulators. On Altirra, the two WSYNC commands seem to occur on scan line 62, but their effects aren’t felt immediately, so perhaps this is what’s causing the DLI to hit on scan line 64 instead of scan line 63. On atari800, the WSYNC commands cause their effects to be felt immediately, in the next command. I would presume that Altirra is closer to what’s going on with real hardware, as the author of Altirra has written the definitive guide to the internals of the machine, and Altirra has always been the leader in cycle-exact emulation.

I think the takeaway from this section is: don’t let your DLI get interrupted by anything else, or it is likely that you will encounter emulation differences.

VBI Interrupting A DLI

For completeness, here is an example of the vertical blank interrupting a DLI.

The DLI is started at the bottom of the screen, gets interrupted by the VBI, and picks up again when VBI ends. Even though the electron beam is turned off, WSYNC is still called and performs its delay function when the scan line is off screen. The resulting image resumes its color cycling background on the top of the screen, stopping after 128 scan lines even though only a fraction of those are actually visible on screen.

DLI on the JVB Instruction

A DLI on the JVB instruction at the end of the display list is possible, but has an interesting property: it triggers DLIs on every scan line until the vertical blank.

If your DLI is not short enough, it will keep getting interrupted by the DLI on triggered by the next scan line, stacking up interrupts until mercifully the triggering process is stopped by the vertical blank after 248 scan lines have been generated.

Note

As each new frame is generated in an emulator, it will enumerate the scan lines starting from zero. There are 248 scan lines before the vertical blank, which will be displayed as scan lines 0 - 247. The scan line labeled 248 will be the first scan line of the vertical blank.

After the vertical blank routine exits, the stacked-up DLI calls will have to unwind themselves so the most recently interrupted DLI (from scan line 247, the scan line just before the vertical blank) will resume and execute code until its RTI. This will pop data off the stack and return control to the DLI that was interrupted on scan line 246, and so-forth until all the interrupted DLIs have issued their RTI instructions.

On a standard length display list that generates 24 blank lines followed by 192 output lines, the JVB instruction will be on scan line 224. Since the JVB technically generates a single blank line in the display list, the DLI will also be triggered on scan line 224. This case would produce 24 DLIs before the vertical blank.

DLIs in a Nutshell

DLIs provide you with a way to notify your program at a particular vertical location on the screen. They pause (or interrupt) the normal flow of program code, save the state of the machine, call your DLI subroutine, and restore the state of the computer before returning control to the code that was interrupted.

Warning

Here are the requirements for successful use of DLIs:

-

your DLI routine must save any registers it clobbers

-

restore any registers you save before exiting

-

exit with an

RTI -

use

WSYNCif necessary -

be aware of cycles stolen by ANTIC: you could have only 60 cycles per scan line in higher resolution graphics modes, and as few as 10 (!) on the first line of text modes

-

store the address of your routine in

VDSLSTbefore enabling DLIs withNMIEN -

guard against the DLI itself being interrupted

Note that nowhere in that list was the requirement that the DLI be short. It doesn’t have to be, and in fact DLIs that span multiple scan lines are similar to kernels used in Atari 2600 programming. The difference is that ANTIC steals cycles depending on a bunch of factors, so the total cycle counting approach (or Racing the Beam) is usually not possible.

However, most DLIs that you will run across in the wild are short, because they typically don’t do a lot of calculations. Most of the setup work will generally be done outside of the DLI and the DLI itself just handles the result of that work.

Advanced DLI Examples

The following examples are available in both source code form and as XEX files at the dli_tutorial source code repository on github.

They are coded using MAC/65 assembler syntax, but very few assembler-specific features are actually used, so they should be trivially ported to other assemblers.

To get a copy of all the examples and source code, you can download and install git for your platform. Then open a command line prompt on your computer and enter the command: git clone https://github.com/playermissile/dli_tutorial.git to download the complete repository.

You can also download individual assembly source and XEX files from links in each section.

In an attempt to de-clutter the examples as much as possible, most of the boilerplate code (for initialization and setup tasks) has been placed in libraries that are included during the compilation process. These are files like util.s, util_dli.s and so forth, and are available in the source code repository or directly here.

#1: Multiple DLIs

One of the problems with having a single DLI vector is: what do you do when you want to have more than one DLI?

Some techniques that you will see in the wild:

use

VCOUNTto check where you are on screen and branch accordinglyincrement an index value and use that to determine which DLI has been called

change the

VDLSTLvector to point to the next DLI in the chain

Here’s an optimization of the last technique that can save some valuable cycles: put your DLIs in the same page of memory and only change the low byte.

*= (* & $ff00) + 256 ; next page boundary dli pha ; only using A register, so save it to the stack lda #$55 ; new background color sta WSYNC ; first WSYNC gets us to start of scan line we want sta COLBK ; change background color lda #<dli2 ; point to second DLI sta VDSLST pla ; restore A register from stack rti ; always end DLI with RTI! dli2 pha ; only using A register, so save it to the stack lda #$88 ; new background color sta WSYNC ; first WSYNC gets us to start of scan line we want sta COLBK ; change background color pla ; restore A register from stack rti ; always end DLI with RTI! vbi lda #<dli ; set DLI pointer to first in chain sta VDSLST lda #>dli sta VDSLST+1 jmp XITVBV ; always exit deferred VBI with jump here

This is a simplistic example, but keeping the high byte constant inside the DLI saves 6 cycles (by obviating the need for changing the high byte with LDA #>dli2; STA VDLSTL+1). That may be enough for this optimization to be useful.

#2: Moving the DLI Up and Down the Screen

The DLI subroutine itself doesn’t directly know what scan line caused the interrupt because all DLIs are routed through the same vector at VDLSTL. The only trigger is in the display list: the DLI bit on the display list instruction.

The display list can be modified in place to move the DLI to different lines without changing any DLI code. The code to move the DLI should be performed in the vertical blank to prevent the display list from being modified as ANTIC is using it to create the display:

move_dli_line ldx last_dli_line ; get line number on screen of old DLI lda dlist_line_lookup,x ; get offset into display list of that line number tax lda dlist_first,x ; remove DLI bit and #$7f sta dlist_first,x ldx dli_line ; get line number on screen of new DLI stx last_dli_line ; remember lda dlist_line_lookup,x ; get offset into display list of that line number tax lda dlist_first,x ; set DLI bit ora #$80 sta dlist_first,x rts

The example allows the display list to be set on blank lines at the top of the display, and on the last mode 4 line in the display list which displays the background below the last mode 4 line on the screen.

Interlude: A Player/Missile Graphics Refresher

Player/Missile Graphics is the sprite system provided by the GTIA: independently positioned overlays on the playfield graphics that don’t disturb the playfield.

Note

the word sprite in this sense wasn’t in use when the Atari was designed, and several sources claim that it was coined by the designers of the Texas Instruments TI 9918 graphics chip at about the same timeframe.

The GTIA provides 4 players with independent colors (from each other or the playfield) and 4 missiles with colors matching their respective player, or the 4 missiles can be combined into a 5th player with its own color (although this reuses one playfield color). The players are 8 bits wide and can be displayed as one, two, or four color clocks wide per bit. This corresponds a width on screen of 8, 16, and 32 color clocks, respectively. Widths for all players and missiles can be set independently.

Each player and missile can be positioned at an arbitrary horizontal location by setting a hardware register, but vertical positioning requires copying data to particular locations in the memory area reserved for it. Each player spans the height of the screen, and it is only the bit pattern in its storage area that determines what is drawn on a particular scan line.

Missiles are two bits wide each with all 4 missiles packed into a single byte for a particular scan line. Bit masking is required to set data for one missile without affecting the others.

The quick summary for our purposes is that horizontal repositioning of players is fast, it takes only a single store instruction. Vertical repositioning of player image data is slow, it requires copying memory around.

#3: Multiplexing Players Vertically

Reusing players (multiplexing) vertically is straightforward, meaning that a single player can be used to display arbitrary images at different vertical locations on the screen, provided that there is no vertical overlap.

Using the hardware HPOSPn or HPOSMn registers, the DLI will immediately change where ANTIC will draw the player or missile. The next time ANTIC draws the player on a scan line, it will use this new position.

in the appropriate player or missile X position register. This demo uses the page-alignment trick for the second DLI, and changes the position and size of the players at each interrupt.

This demo splits the screen vertically into 3 horizontal bands, A, B & C, with the players extending the full height of the screen and labeled 0 through 3. This example uses the VBI to set the players for band A, the dli routine is the bottom of band A (and the top of band B) and therefore sets the players for band B, and the dli2 routine is the bottom of band B (and the top of band C) and controls the players for band C.

vbi lda #<dli ; set DLI pointer to first in chain sta VDSLST lda #>dli sta VDSLST+1 lda #$40 ; set player positions and sizes ... sta HPOSP0 ; for the top of the screen lda #$60 sta HPOSP1 lda #$80 sta HPOSP2 lda #$a0 sta HPOSP3 lda #0 sta SIZEP0 sta SIZEP1 sta SIZEP2 sta SIZEP3 jmp XITVBV ; always exit deferred VBI with jump here *= (* & $ff00) + 256 ; next page boundary dli pha ; only using A register, so save it to the stack lda #$55 ; new background color sta WSYNC ; first WSYNC gets us to start of scan line we want sta COLBK ; change background color lda #$30 ; change position and sizes of players sta HPOSP0 lda #$40 sta HPOSP1 lda #$50 sta HPOSP2 lda #$60 sta HPOSP3 lda #1 sta SIZEP0 sta SIZEP1 sta SIZEP2 sta SIZEP3 lda #<dli2 ; point to second DLI sta VDSLST pla ; restore A register from stack rti ; always end DLI with RTI! dli2 pha ; only using A register, so save it to the stack lda #$84 ; new background color sta WSYNC ; first WSYNC gets us to start of scan line we want sta COLBK ; change background color lda #$40 ; change position and sizes of players sta HPOSP0 lda #$70 sta HPOSP1 lda #$90 sta HPOSP2 lda #$b0 sta HPOSP3 lda #3 sta SIZEP0 sta SIZEP1 sta SIZEP2 sta SIZEP3 pla ; restore A register from stack rti ; always end DLI with RTI!

In discussing the timing issues that cause errors at the band boundaries, the players in band A are positioned by the VBI, and so are in place from well off the top of the screen and are correctly positioned at the first scan line. Players 0, 1, and 2 are correct at the bottom of the band, but player 3 extends one scan line too far, into band B.

The top of band B shows both position and size errors. When the first DLI hits on the last scan line of the 6th line of text, the background color is changed at the WSYNC and ANTIC moves on to start drawing the first scan line of the 7th line of text (which is the first line of text in band B.) Players 0, 1, and 2 are positioned correctly, which means their horizontal positions were set before ANTIC reached that portion of the scan line. The 3rd player remains in the same position as it was in band A, meaning that its horizontal position wasn’t set in time. ANTIC had stolen enough cycles setting up the mode 4 font that the 6502 didn’t get a chance to process the sta HPOS3 before ANTIC had to draw that portion of the scan line. Since the code sets sizes after the horizontal positions, none of the sizes are set until the 2nd scan line of band B.

The transition to band C with the dli2 routine produces similar results, there just isn’t enough time with the WSYNC used for the color change and all the cycles stolen by ANTIC mode 4 to process the all of the player changes in the first scan line of the band. Players 0, 1, and 2 are moved, player 3 is not, and all 4 players don’t get the correct size until the 2nd scan line of the band.

It’s possible to imagine a scenario where a scan line of a player is not visible at all. For example, if player 3 above had been positioned very far to the right and HPOSP3 was changed to move player 3 to the far left side, it could be possible that ANTIC has already drawn the left side of the screen but hadn’t yet reached the right side where player 3 had been positioned. Because HPOSP3 is now showing that player 3 is on the left side of the screen, ANTIC would not draw it at its old location on the right side of the screen.

It’s also possible, with careful timing, to reuse a player on a single line. However, purposeful use of this would difficult given all the different horizontal locations of ANTIC’s cycle stealing.

Mode 4 was chosen (in all of its cycle-stealing glory) for these examples to get an idea of the worst-case scenerio. Taking out the WSYNC and the color change did allow enough time that both the positions and sizes were changed without visible artifacts:

but this is very simple code and the more real-world example in the next section will show that a buffer zone of several scan lines is necessary to make sure a player isn’t split across a band boundary or, as described above, even duplicating a line of the player or missing a scan line.

#4: Multiplexing With Horizontal Motion

Increasing the number of bands and adding independent player movement within each band requires some data structures and a DLI to control placement in each band.

The approach used in this example is to use a single DLI that uses an index value to determine which band it is operating within. This index value is used as an offset into arrays that hold the sprite X position, size, color, etc.

There are a lot of independently moving objects in this demo: 12 bands, each with 4 players. There are very obvious timing issues in most bands on the first scan line after the DLI as sometimes the hardware registers for a player hasn’t been updated fully until the second scan line.

; same DLI routine is used for each band, the band_dli_index is used to set ; player information for the appropriate band dli_band pha ; using A & X txa pha inc band_dli_index ; increment band index, VBI initialized to $ff, ldx band_dli_index ; so will become 0 for band A ; control band X positions of players lda bandp0_x,x ; x position of player 0 in this band sta HPOSP0 lda bandp0_color,x ; color of player 0 for this band sta COLPM0 lda bandp0_size,x ; size of player 0 for this band sta SIZEP0 lda bandp1_x,x ; as above, but for players 1 - 3 sta HPOSP1 lda bandp1_color,x sta COLPM1 lda bandp1_size,x sta SIZEP1 lda bandp2_x,x sta HPOSP2 lda bandp2_color,x sta COLPM2 lda bandp2_size,x sta SIZEP2 lda bandp3_x,x sta HPOSP3 lda bandp3_color,x sta COLPM3 lda bandp3_size,x sta SIZEP3 ?done pla ; restore A & X tax pla rti ; always end DLI with RTI!

The addreses bandpN_x, bandpN_color, and bandpN_size (where N is the player number) are declared as lists with the number of entries equal to the number of bands. band_dli_index is incremented each time the DLI starts, and uses that index into the lists so it places the players in the correct location for that band.

Notice that is all the DLI does. It does not calculate movement or perform any player logic, it simply puts players on the screen in the appropriate place for that band. All the calculation is done in the vertical blank:

; calculate new positions of players in all bands vbi ldx #0 ?move lda bandp0_x,x ; update X coordinate clc ; by adding velocity. adc bandp0_dx,x ; Note that velocity of $ff sta bandp0_x,x ; is same as -1 cmp #$30 ; check left edge bcs ?right ; if >=, it is still in playfield lda #1 ; nope, <, so make velocity positive sta bandp0_dx,x bne ?cont ?right cmp #$c0 ; check right edge bcc ?cont ; if <, it is still in playfield lda #$ff ; nope, >=, so make velocity negative sta bandp0_dx,x ?cont inx ; next player cpx #num_dli_bands * 4 ; loop through 12 bands * 4 players each bcc ?move lda #$ff ; initialize band index to get ready for band A sta band_dli_index jmp XITVBV ; always exit deferred VBI with jump here

Unlike the simple multiplexing demo in the previous section, this VBI does not set any positions of players. Instead, this demo sets the DLI bit on the last group of 8 blank lines at the beginning of the display list, before any mode 4 lines. This initial DLI will set the players for band A, and as you can see in the demo the players above band A use the same X position and size as band L. The colors are not the same as band L, however, because of the use of the shadow registers to set the initial color in the init_pmg subroutine.

#n: Multiplexing with Arbitrary Motion

Vertical movement within bands requires the moving memory around the player/missile graphics area (pointed to by PMBASE) as in normal usage, with the following limitations:

players must stay within their assigned band, otherwise they will get split across bands when the DLI occurs.

players should avoid the first few scan lines below the top of the band boundary to prevent splitting

when moving a player vertically within a band, only erase data from that band to prevent affecting the multiplexed players in other bands

<example goes here>

#n: Multiplexing With Collision Detection

If it is important to tell in which band a has collided occurred, the DLI that starts a new band will be required to save the collision status registers, which will determine if a collision happened in the previous band. It will then reset the collision registers so the following DLI can check what happened in this band.

If the knowledge of the band is not important, you can just check the collision registers in the vertical blank, which will report if there have been any collisions with anything in any band.

<example goes here>

#n: Multiplexing Players Horizontally

Reusing players on the same scan line is possible, but its usefulness may be limited to mostly static cases.

<example goes here>

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/361GQA7

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.