About

LPython is a Python compiler that can compile type-annotated Python code to optimized machine code. LPython offers several backends such as LLVM, C, C++, WASM, Julia and x86. LPython features quick compilation and runtime performance, as we show in the benchmarks in this blog. LPython also offers Just-In-Time (JIT) compilation and seamless interoperability with CPython.

We are releasing an alpha version of LPython, meaning it is expected you encounter bugs when you use it (please report them!). You can install it using Conda (conda install -c conda-forge lpython), or build from source.

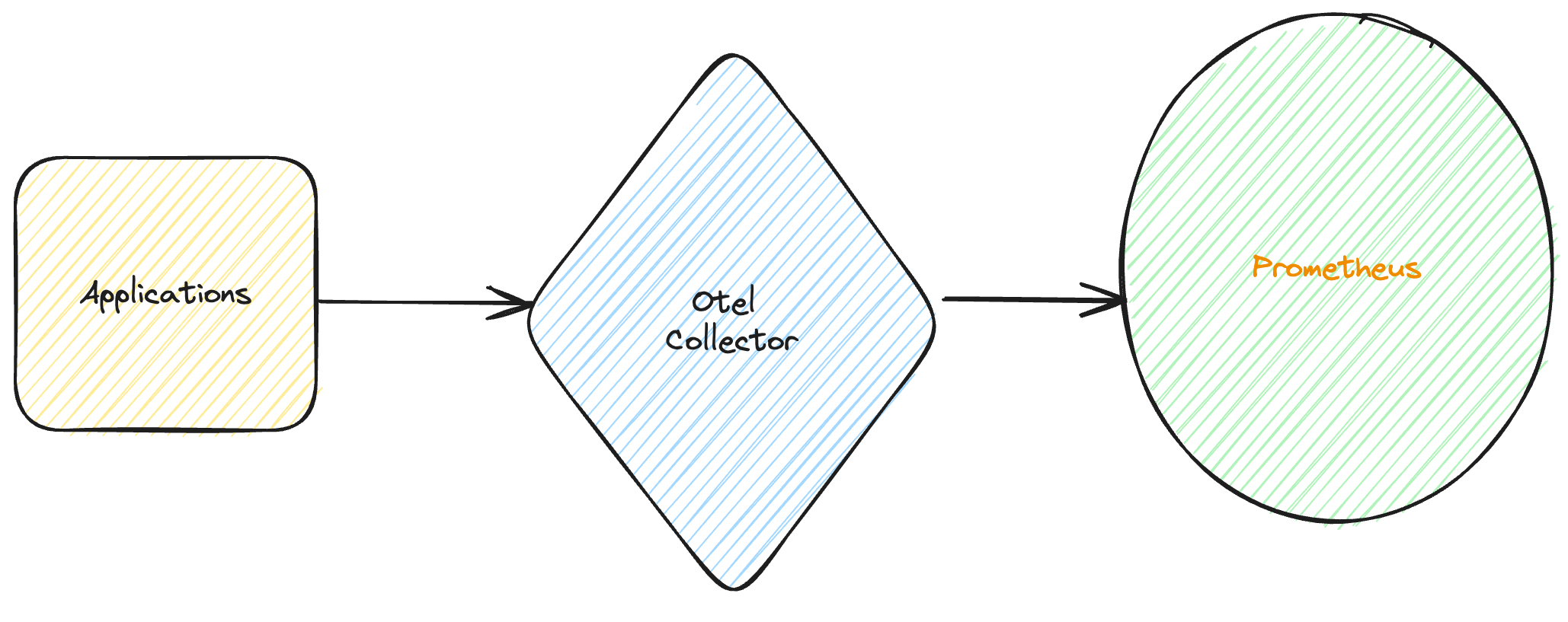

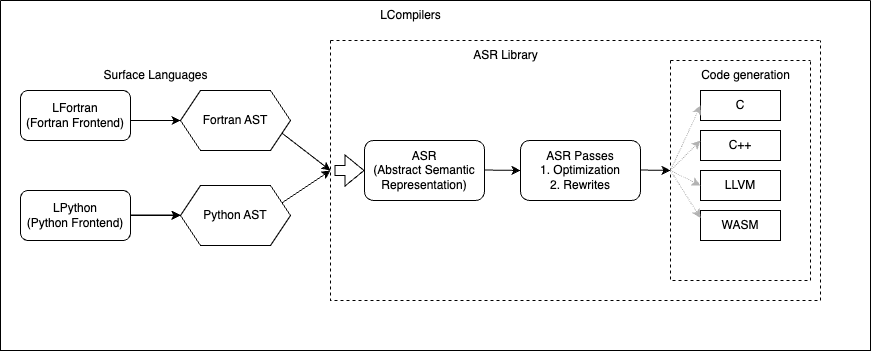

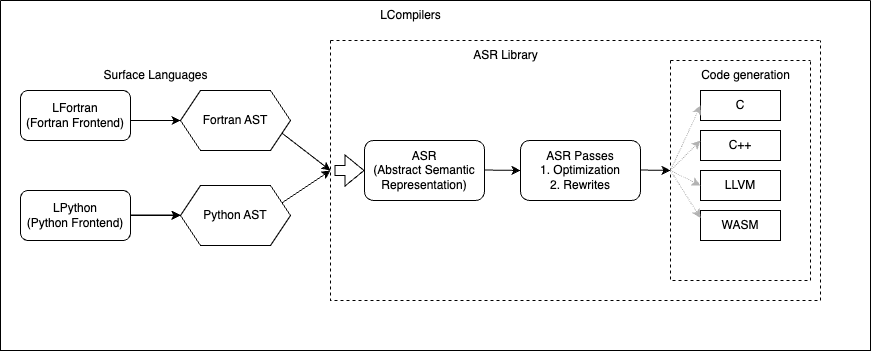

Based on the novel Abstract Semantic Representation (ASR) shared with LFortran, LPython’s intermediate optimizations are independent of the backends and frontends. The two compilers, LPython and LFortran, share all benefits of improvements at the ASR level. “Speed” is the chief tenet of the LPython project. Our objective is to produce a compiler that both runs exceptionally fast and generates exceptionally fast code.

In this blog, we describe features of LPython including Ahead-of-Time (AoT) compilation, JIT compilation, and interoperability with CPython. We also showcase LPython’s performance against its competitors such as Numba and C++ via several benchmarks.

Features of LPython

Backends

LPython ships with the following backends, which emit final translations of the user’s input code:

- LLVM

- C

- C++

- WASM

LPython can simultaneously generate code into multiple backends from its Abstract Semantic Representation (ASR) of user code.

Phases of Compilation

First, input code is transformed into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) using parsers. The AST is then transformed into an Abstract Semantic Representation (ASR), which preserves all semantic information present in the input code. ASR contains all information required by all backends in a form that is not specific to any particular backend. Then, this ASR enjoys several ASR-to-ASR passes, wherein abstract operations are transformed into concrete statements. For example, array addition in the input code denoted, c = a + b. The front end transforms c = a + b into the ASR (Assign c (ArrayAdd a b)) via operator overloading. The array_op ASR-to-ASR pass transforms (Assign c (ArrayAdd a b)) into loops:

for i0 in range(0, length_dim_0):

for i1 in range(0, length_dim_1):

....

....

c[i0, i1, ...] = a[i0, i1, ...] + b[i0, i1, ...]

After applying all the ASR-to-ASR passes, LPython sends the final ASR to the backends selected by the user, via command-line arguments like, --show-c (generates C code), --show-llvm (generates LLVM code).

One can also see the generated C or LLVM code using the following

from lpython import i32

def main():

x: i32

x = (2+3)*5

print(x)

main()

$ lpython examples/expr2.py --show-c

#include <inttypes.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdbool.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <lfortran_intrinsics.h>

void main0();

void __main____global_statements();

// Implementations

void main0()

{

int32_t x;

x = (2 + 3)*5;

printf("%d\n", x);

}

void __main____global_statements()

{

main0();

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

_lpython_set_argv(argc, argv);

__main____global_statements();

return 0;

}

$ lpython examples/expr2.py --show-llvm

; ModuleID = 'LFortran'

source_filename = "LFortran"

@0 = private unnamed_addr constant [2 x i8] c" \00", align 1

@1 = private unnamed_addr constant [2 x i8] c"\0A\00", align 1

@2 = private unnamed_addr constant [5 x i8] c"%d%s\00", align 1

define void @__module___main_____main____global_statements() {

.entry:

call void @__module___main___main0()

br label %return

return: ; preds = %.entry

ret void

}

define void @__module___main___main0() {

.entry:

%x = alloca i32, align 4

store i32 25, i32* %x, align 4

%0 = load i32, i32* %x, align 4

call void (i8*, ...) @_lfortran_printf(i8* getelementptr inbounds ([5 x i8], [5 x i8]* @2, i32 0, i32 0), i32 %0, i8* getelementptr inbounds ([2 x i8], [2 x i8]* @1, i32 0, i32 0))

br label %return

return: ; preds = %.entry

ret void

}

declare void @_lfortran_printf(i8*, ...)

define i32 @main(i32 %0, i8** %1) {

.entry:

call void @_lpython_set_argv(i32 %0, i8** %1)

call void @__module___main_____main____global_statements()

ret i32 0

}

declare void @_lpython_set_argv(i32, i8**)

Machine Independent Code Optimisations

LPython implements several machine-independent optimisations via ASR-to-ASR passes. Some of those are listed below,

- Loop unrolling

- Loop vectorisation

- Dead code removal

- Function call inlining

- Transforming division to multiplication operation

- Fused multiplication and addition

All optimizations are applied via one command-line argument, --fast. To select individual optimizations instead, write a command-line argument like the following:

--pass=inline_function_calls,loop_unroll

Following is an examples of ASR and transformed ASR after applying the optimisations

from lpython import i32

def compute_x() -> i32:

return (2 * 3) ** 1 + 2

def main():

x: i32 = compute_x()

print(x)

main()

$ lpython examples/expr2.py --show-asr

(TranslationUnit

(SymbolTable

1

{

__main__:

(Module

(SymbolTable

2

{

__main____global_statements:

(Function

(SymbolTable

5

{

})

__main____global_statements

(FunctionType

[]

()

Source

Implementation

()

.false.

.false.

.false.

.false.

.false.

[]

[]

.false.

)

[main]

[]

[(SubroutineCall

2 main

()

[]

()

)]

()

Public

.false.

.false.

()

),

compute_x:

(Function

(SymbolTable

3

{

_lpython_return_variable:

(Variable

3

_lpython_return_variable

[]

ReturnVar

()

()

Default

(Integer 4)

()

Source

Public

Required

.false.

)

})

compute_x

(FunctionType

[]

(Integer 4)

Source

Implementation

()

.false.

.false.

.false.

.false.

.false.

[]

[]

.false.

)

[]

[]

[(=

(Var 3 _lpython_return_variable)

(IntegerBinOp

(IntegerBinOp

(IntegerBinOp

(IntegerConstant 2 (Integer 4))

Mul

(IntegerConstant 3 (Integer 4))

(Integer 4)

(IntegerConstant 6 (Integer 4))

)

Pow

(IntegerConstant 1 (Integer 4))

(Integer 4)

(IntegerConstant 6 (Integer 4))

)

Add

(IntegerConstant 2 (Integer 4))

(Integer 4)

(IntegerConstant 8 (Integer 4))

)

()

)

(Return)]

(Var 3 _lpython_return_variable)

Public

.false.

.false.

()

),

main:

(Function

(SymbolTable

4

{

x:

(Variable

4

x

[]

Local

()

()

Default

(Integer 4)

()

Source

Public

Required

.false.

)

})

main

(FunctionType

[]

()

Source

Implementation

()

.false.

.false.

.false.

.false.

.false.

[]

[]

.false.

)

[compute_x]

[]

[(=

(Var 4 x)

(FunctionCall

2 compute_x

()

[]

(Integer 4)

()

()

)

()

)

(Print

()

[(Var 4 x)]

()

()

)]

()

Public

.false.

.false.

()

)

})

__main__

[]

.false.

.false.

),

main_program:

(Program

(SymbolTable

6

{

__main____global_statements:

(ExternalSymbol

6

__main____global_statements

2 __main____global_statements

__main__

[]

__main____global_statements

Public

)

})

main_program

[__main__]

[(SubroutineCall

6 __main____global_statements

2 __main____global_statements

[]

()

)]

)

})

[]

)

$ lpython examples/expr2.py --show-asr --pass=inline_function_calls,unused_functions

(TranslationUnit

(SymbolTable

1

{

__main__:

(Module

(SymbolTable

2

{

__main____global_statements:

(Function

(SymbolTable

5

{

})

__main____global_statements

(FunctionType

[]

()

Source

Implementation

()

.false.

.false.

.false.

.false.

.false.

[]

[]

.false.

)

[main]

[]

[(SubroutineCall

2 main

()

[]

()

)]

()

Public

.false.

.false.

()

),

main:

(Function

(SymbolTable

4

{

_lpython_return_variable_compute_x:

(Variable

4

_lpython_return_variable_compute_x

[]

Local

()

()

Default

(Integer 4)

()

Source

Public

Required

.false.

),

x:

(Variable

4

x

[]

Local

()

()

Default

(Integer 4)

()

Source

Public

Required

.false.

),

~empty_block:

(Block

(SymbolTable

7

{

})

~empty_block

[]

)

})

main

(FunctionType

[]

()

Source

Implementation

()

.false.

.false.

.false.

.false.

.false.

[]

[]

.false.

)

[]

[]

[(=

(Var 4 _lpython_return_variable_compute_x)

(IntegerBinOp

(IntegerBinOp

(IntegerBinOp

(IntegerConstant 2 (Integer 4))

Mul

(IntegerConstant 3 (Integer 4))

(Integer 4)

(IntegerConstant 6 (Integer 4))

)

Pow

(IntegerConstant 1 (Integer 4))

(Integer 4)

(IntegerConstant 6 (Integer 4))

)

Add

(IntegerConstant 2 (Integer 4))

(Integer 4)

(IntegerConstant 8 (Integer 4))

)

()

)

(GoTo

1

__1

)

(BlockCall

1

4 ~empty_block

)

(=

(Var 4 x)

(Var 4 _lpython_return_variable_compute_x)

()

)

(Print

()

[(Var 4 x)]

()

()

)]

()

Public

.false.

.false.

()

)

})

__main__

[]

.false.

.false.

),

main_program:

(Program

(SymbolTable

6

{

__main____global_statements:

(ExternalSymbol

6

__main____global_statements

2 __main____global_statements

__main__

[]

__main____global_statements

Public

)

})

main_program

[__main__]

[(SubroutineCall

6 __main____global_statements

2 __main____global_statements

[]

()

)]

)

})

[]

)

Ahead-of-Time (AoT) compilation

LPython naturally acts as a Python compiler. By default, if no backend is provided it compiles type-annotated user input code to LLVM, which generates binary final output. Consider the following small example:

from lpython import i32, i64

def list_bench(n: i32) -> i64:

x: list[i32]

x = []

i: i32

for i in range(n):

x.append(i)

s: i64 = i64(0)

for i in range(n):

s += i64(x[i])

return s

res: i64 = list_bench(500_000)

print(res)

(lp) 18:58:29:~/lpython_project/lpython % lpython /Users/czgdp1807/lpython_project/debug.py -o a.out

(lp) 18:58:31:~/lpython_project/lpython % time ./a.out

124999750000

./a.out 0.01s user 0.00s system 89% cpu 0.012 total

You can see that it’s very fast. It’s still plenty fast with the C backend via the command-line argument --backend=c:

% time lpython /Users/czgdp1807/lpython_project/debug.py --backend=c

124999750000

lpython /Users/czgdp1807/lpython_project/debug.py --backend=c 0.12s user 0.02s system 100% cpu 0.144 total

Note that time lpython /Users/czgdp1807/lpython_project/debug.py --backend=c includes both the compilation time of LPython and the execution time of the binary. The sum of both is so fast that one can afford to compile on every change to the input files. :D.

Just-In-Time Compilation

Just-in-time compilation in LPython requires only decorating Python function with @lpython. The decorator takes an option for specifying the desired backend, as in, @lpython(backend="c") or @lpython(backend="llvm"). Only C is supported at present; LLVM and others will be added in the near future. The decorator also propagates backend-specific options. For example

@lpython(backend="c",

backend_optimization_flags=["-ffast-math",

"-funroll-loops",

"-O1"])

Note that by default C backend is used without any optimisation flags.

A small example of JIT compilation in LPython (notice the LPython type annotations with the variables),

from lpython import i32, i64, lpython

@lpython(backend="c", backend_optimisation_flags=["-ffast-math", "-funroll-loops", "-O1"])

def list_bench(n: i32) -> i64:

x: list[i32]

x = []

i: i32

for i in range(n):

x.append(i)

s: i64 = i64(0)

for i in range(n):

s += i64(x[i])

return s

res = list_bench(1) # compiles `list_bench` to a shared binary in the first call

res = list_bench(500_000) # calls the compiled `list_bench`

print(res)

(lp) 18:46:33:~/lpython_project/lpython % python /Users/czgdp1807/lpython_project/debug.py

124999750000

We show below in the benchmarks how LPython compares to Numba, which also has JIT compilation.

Inter-operability with CPython

Access any library implemented using CPython, via the @pythoncall decorator. For example,

email_extractor.py

# get_email is implemented in email_extractor_util.py which is intimated to

# LPython by specifiying the file as module in `@pythoncall` decorator

@pythoncall(module="email_extractor_util")

def get_email(text: str) -> str:

pass

def test():

text: str = "Hello, my email id is lpython@lcompilers.org."

print(get_email(text))

test()

email_extractor_util.py

# Implement `get_email` using `re` CPython library

def get_email(text):

import re

# Regular expression patterns

email_pattern = r"\b[A-Za-z0-9._%+-]+@[A-Za-z0-9.-]+\.[A-Za-z]{2,}\b"

# Matching email addresses

email_matches = re.findall(email_pattern, text)

return email_matches[0]

(lp) 18:54:13:~/lpython_project % lpython email_extractor.py --backend=c --enable-cpython

lpython@lcompilers.org

Note: The @pythoncall and @lpython decorators are presently supported with just the C backend but eventually will work with the LLVM backend and that’s work in progress.

Benchmarks and Demos

In this section, we show how LPython performs compares to competitors on each feature LPython offers. We cover JIT compilation, Interoperability with CPython, and AoT compilation.

Just-In-Time (JIT) Compilation

We compare JIT compilation of LPython to Numba on summation of all the elements of a 1-D array, pointwise multiplication of two 1-D arrays, insertion sort on lists, and quadratic-time implementation of the Dijkstra shortest-path algorithm on a fully connected graph.

System Information

| Compiler |

Version |

| Numba |

0.57.1 |

| LPython |

0.19.0 |

| Python |

3.10.4 |

Summation of all the elements of a 1-D array

from numpy import float64, arange, empty

from lpython import i32, f64, lpython

import timeit

from numba import njit

@lpython(backend="c", backend_optimisation_flags=["-ffast-math", "-funroll-loops", "-O3"])

def fast_sum(n: i32, x: f64[:], res: f64[:]) -> f64:

s: f64 = 0.0

res[0] = 0.0

i: i32

for i in range(n):

s += x[i]

res[0] = s

return s

@njit(fastmath=True)

def fast_sum_numba(n, x, res):

s = 0.0

res[0] = 0.0

for i in range(n):

s += x[i]

res[0] = s

return s

def test():

n = 100_000_000

x = arange(n, dtype=float64)

x1 = arange(0, dtype=float64)

res = empty(1, dtype=float64)

res_numba = empty(1, dtype=float64)

print("LPython compilation time:", timeit.timeit(lambda: fast_sum(0, x1, res), number=1))

print("LPython execution time: ", min(timeit.repeat(lambda: fast_sum(n, x, res), repeat=10, number=1)))

assert res[0] == 4999999950000000.0

print("Numba compilation time:", timeit.timeit(lambda: fast_sum_numba(0, x1, res_numba), number=1))

print("Numba execution time:", min(timeit.repeat(lambda: fast_sum_numba(n, x, res_numba), repeat=10, number=1)))

assert res_numba[0] == 4999999950000000.0

test()

| Compiler |

Compilation Time (s) |

System |

Relative |

| Numba |

0.10 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

1.00 |

| LPython |

0.20 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

2.00 |

| Numba |

0.08 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

1.00 |

| LPython |

0.53 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

6.62 |

| Numba |

0.15 |

Apple M1 2020 |

1.00 |

| LPython |

0.40 |

Apple M1 2020 |

2.67 |

| Numba |

0.20 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

1.00 |

| LPython |

0.32 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

1.60 |

| Compiler |

Execution Time (s) |

System |

Relative |

| LPython |

0.013 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

1.00 |

| Numba |

0.024 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

1.84 |

| LPython |

0.013 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

1.00 |

| Numba |

0.023 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

1.77 |

| LPython |

0.014 |

Apple M1 2020 |

1.00 |

| Numba |

0.024 |

Apple M1 2020 |

1.71 |

| LPython |

0.048 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

1.00 |

| Numba |

0.048 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

1.00 |

Pointwise multiplication of two 1-D arrays

from numpy import int64, arange, empty

from lpython import i32, i64, lpython

import timeit

from numba import njit

@lpython(backend="c", backend_optimisation_flags=["-ffast-math", "-funroll-loops", "-O3"])

def multiply_arrays(n: i32, x: i64[:], y: i64[:], z: i64[:]):

i: i32

for i in range(n):

z[i] = x[i] * y[i]

@njit(fastmath=True)

def multiply_arrays_numba(n, x, y, z):

for i in range(n):

z[i] = x[i] * y[i]

def test():

n = 100_000_000

x1 = arange(0, dtype=int64)

y1 = arange(0, dtype=int64)

res1 = arange(0, dtype=int64)

x = arange(n, dtype=int64)

y = arange(n, dtype=int64) + 2

res = empty(n, dtype=int64)

res_numba = empty(n, dtype=int64)

print("LPython compilation time:", timeit.timeit(lambda: multiply_arrays(0, x1, y1, res1), number=1))

print("LPython execution time:", min(timeit.repeat(lambda: multiply_arrays(n, x, y, res), repeat=10, number=1)))

assert sum(res - x * y) == 0

print("Numba compilation time:", timeit.timeit(lambda: multiply_arrays_numba(0, x1, y1, res1), number=1))

print("Numba execution time:", min(timeit.repeat(lambda: multiply_arrays_numba(n, x, y, res_numba), repeat=10, number=1)))

assert sum(res_numba - x * y) == 0

test()

| Compiler |

Compilation Time (s) |

System |

Relative |

| Numba |

0.11 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

1.00 |

| LPython |

0.50 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

4.54 |

| Numba |

0.09 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

1.00 |

| LPython |

0.60 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

6.67 |

| Numba |

0.11 |

Apple M1 2020 |

1.00 |

| LPython |

0.46 |

Apple M1 2020 |

4.18 |

| Numba |

0.21 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

1.00 |

| LPython |

0.31 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

1.48 |

| Compiler |

Execution Time (s) |

System |

Relative |

| Numba |

0.041 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

1.00 |

| LPython |

0.042 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

1.02 |

| Numba |

0.037 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

1.00 |

| LPython |

0.040 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

1.08 |

| Numba |

0.042 |

Apple M1 2020 |

1.00 |

| LPython |

0.042 |

Apple M1 2020 |

1.00 |

| Numba |

0.21 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

1.00 |

| LPython |

0.21 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

1.00 |

Insertion sort on lists

from lpython import i32, lpython

import timeit

from numba import njit

@lpython(backend="c", backend_optimisation_flags=["-ffast-math", "-funroll-loops", "-O3"])

def test_list_sort(size: i32):

i: i32

x: list[i32]

x = []

for i in range(size):

x.append(size - i)

for i in range(1, size):

key: i32 = x[i]

j: i32 = i - 1

while j >= 0 and key < x[j] :

x[j + 1] = x[j]

j -= 1

x[j + 1] = key

for i in range(1, size):

assert x[i - 1] < x[i]

@njit(fastmath=True)

def test_list_sort_numba(size):

x = []

for i in range(size):

x.append(size - i)

for i in range(1, size):

key = x[i]

j = i - 1

while j >= 0 and key < x[j] :

x[j + 1] = x[j]

j -= 1

x[j + 1] = key

for i in range(1, size):

assert x[i - 1] < x[i]

def test():

n = 25000

print("LPython compilation time:", timeit.timeit(lambda: test_list_sort(0), number=1))

print("LPython execution time:", min(timeit.repeat(lambda: test_list_sort(n), repeat=10, number=1)))

print("Numba compilation time:", timeit.timeit(lambda: test_list_sort_numba(0), number=1))

print("Numba execution time:", min(timeit.repeat(lambda: test_list_sort_numba(n), repeat=10, number=1)))

test()

| Compiler |

Compilation Time (s) |

System |

Relative |

| Numba |

0.13 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

1.00 |

| LPython |

0.20 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

1.54 |

| Numba |

0.13 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

1.00 |

| LPython |

0.60 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

4.62 |

| Numba |

0.13 |

Apple M1 2020 |

1.00 |

| LPython |

0.42 |

Apple M1 2020 |

3.23 |

| Numba |

0.35 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

1.00 |

| LPython |

0.37 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

1.06 |

| Compiler |

Execution Time (s) |

System |

Relative |

| LPython |

0.11 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

1.00 |

| Numba |

0.39 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

3.54 |

| LPython |

0.11 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

1.00 |

| Numba |

0.39 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

3.54 |

| LPython |

0.20 |

Apple M1 2020 |

1.00 |

| Numba |

0.39 |

Apple M1 2020 |

1.95 |

| LPython |

0.10 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

1.00 |

| Numba |

0.36 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

3.60 |

Quadratic-time implementation of the Dijkstra shortest-path algorithm on a fully connected graph

from lpython import i32, lpython

from numpy import empty, int32

from numba import njit

import timeit

@lpython(backend="c", backend_optimisation_flags=["-ffast-math", "-funroll-loops", "-O1"])

def dijkstra_shortest_path(n: i32, source: i32, dist_sum: i32[:]):

i: i32; j: i32; v: i32; u: i32; mindist: i32; alt: i32; dummy: i32;

graph: dict[i32, i32] = {}

dist: dict[i32, i32] = {}

prev: dict[i32, i32] = {}

visited: dict[i32, bool] = {}

Q: list[i32] = []

for i in range(n):

for j in range(n):

graph[n * i + j] = abs(i - j)

for v in range(n):

dist[v] = 2147483647

prev[v] = -1

Q.append(v)

visited[v] = False

dist[source] = 0

while len(Q) > 0:

u = -1

mindist = 2147483647

for i in range(len(Q)):

if mindist > dist[Q[i]]:

mindist = dist[Q[i]]

u = Q[i]

Q.remove(u)

visited[u] = True

for v in range(n):

if v != u and not visited[v]:

alt = dist[u] + graph[n * u + v]

if alt < dist[v]:

dist[v] = alt

prev[v] = u

dist_sum[0] = 0

for i in range(n):

dist_sum[0] += dist[i]

@njit(fastmath=True)

def dijkstra_shortest_path_numba(n, source, dist_sum):

graph = {}

dist = {}

prev = {}

visited = {}

Q = []

for i in range(n):

for j in range(n):

graph[n * i + j] = abs(i - j)

for v in range(n):

dist[v] = 2147483647

prev[v] = -1

Q.append(v)

visited[v] = False

dist[source] = 0

while len(Q) > 0:

u = -1

mindist = 2147483647

for i in range(len(Q)):

if mindist > dist[Q[i]]:

mindist = dist[Q[i]]

u = Q[i]

Q.remove(u)

visited[u] = True

for v in range(n):

if v != u and not visited[v]:

alt = dist[u] + graph[n * u + v]

if alt < dist[v]:

dist[v] = alt

prev[v] = u

dist_sum[0] = 0

for i in range(n):

dist_sum[0] += dist[i]

def test():

n: i32 = 4000

dist_sum_array_numba = empty(1, dtype=int32)

dist_sum_array = empty(1, dtype=int32)

print("LPython compilation time: ", timeit.timeit(lambda: dijkstra_shortest_path(0, 0, dist_sum_array), number=1))

print("LPython execution time: ", min(timeit.repeat(lambda: dijkstra_shortest_path(n, 0, dist_sum_array), repeat=5, number=1)))

print(dist_sum_array[0])

assert dist_sum_array[0] == i32(n * (n - 1)/2)

print("Numba compilation time: ", timeit.timeit(lambda: dijkstra_shortest_path_numba(0, 0, dist_sum_array_numba), number=1))

print("Numba execution time: ", min(timeit.repeat(lambda: dijkstra_shortest_path_numba(n, 0, dist_sum_array_numba), repeat=5, number=1)))

print(dist_sum_array_numba[0])

assert dist_sum_array_numba[0] == i32(n * (n - 1)/2)

test()

| Compiler |

Compilation Time (s) |

System |

Relative |

| LPython |

0.35 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

1.00 |

| Numba |

0.81 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

2.31 |

| LPython |

0.69 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

1.00 |

| Numba |

0.73 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

1.05 |

| LPython |

0.21 |

Apple M1 2020 |

1.00 |

| Numba |

0.73 |

Apple M1 2020 |

3.47 |

| LPython |

1.08 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

1.00 |

| Numba |

1.69 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

1.56 |

| Compiler |

Execution Time (s) |

System |

Relative |

| LPython |

0.23 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

1.00 |

| Numba |

1.01 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

4.39 |

| LPython |

0.20 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

1.00 |

| Numba |

0.98 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

4.90 |

| LPython |

0.27 |

Apple M1 2020 |

1.00 |

| Numba |

0.98 |

Apple M1 2020 |

3.63 |

| LPython |

0.87 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

1.00 |

| Numba |

1.95 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

2.24 |

Ahead-of-Time (AoT) Compilation

Next, we see how LPython compares to other AoT compilers and to the standard CPython interpreter. The tasks considered are quadratic-time implementation of the Dijkstra shortest-path algorithm on a fully connected graph, and Floyd-Warshall algorithm on array representation of graphs.

System Information

| Compiler |

Version |

| clang++ |

14.0.3 |

| g++ |

11.3.0 |

| LPython |

0.19.0 |

| Python |

3.10.4 |

Quadratic-time implementation of the Dijkstra shortest-path algorithm on a fully connected graph

from lpython import i32

def dijkstra_shortest_path(n: i32, source: i32) -> i32:

i: i32; j: i32; v: i32; u: i32; mindist: i32; alt: i32; dummy: i32; uidx: i32

dist_sum: i32;

graph: dict[i32, i32] = {}

dist: dict[i32, i32] = {}

prev: dict[i32, i32] = {}

visited: dict[i32, bool] = {}

Q: list[i32] = []

for i in range(n):

for j in range(n):

graph[n * i + j] = abs(i - j)

for v in range(n):

dist[v] = 2147483647

prev[v] = -1

Q.append(v)

visited[v] = False

dist[source] = 0

while len(Q) > 0:

u = -1

mindist = 2147483647

for i in range(len(Q)):

if mindist > dist[Q[i]]:

mindist = dist[Q[i]]

u = Q[i]

uidx = i

dummy = Q.pop(uidx)

visited[u] = True

for v in range(n):

if v != u and not visited[v]:

alt = dist[u] + graph[n * u + v]

if alt < dist[v]:

dist[v] = alt

prev[v] = u

dist_sum = 0

for i in range(n):

dist_sum += dist[i]

return dist_sum

def test():

n: i32 = 4000

print(dijkstra_shortest_path(n, 0))

test()

#include <iostream>

#include <unordered_map>

#include <vector>

int32_t dijkstra_shortest_path(int32_t n, int32_t source) {

int32_t i, j, v, u, mindist, alt, dummy, uidx;

std::unordered_map<int32_t, int32_t> graph, dist, prev;

std::unordered_map<int32_t, bool> visited;

std::vector<int32_t> Q;

for(i = 0; i < n; i++) {

for(j = 0; j < n; j++) {

graph[n * i + j] = std::abs(i - j);

}

}

for(v = 0; v < n; v++) {

dist[v] = 2147483647;

prev[v] = -1;

Q.push_back(v);

visited[v] = false;

}

dist[source] = 0;

while(Q.size() > 0) {

u = -1;

mindist = 2147483647;

for(i = 0; i < Q.size(); i++) {

if( mindist > dist[Q[i]] ) {

mindist = dist[Q[i]];

u = Q[i];

uidx = i;

}

}

Q.erase(Q.begin() + uidx);

visited[u] = true;

for(v = 0; v < n; v++) {

if( v != u and not visited[v] ) {

alt = dist[u] + graph[n * u + v];

if( alt < dist[v] ) {

dist[v] = alt;

prev[v] = u;

}

}

}

}

int32_t dist_sum = 0;

for(i = 0; i < n; i++) {

dist_sum += dist[i];

}

return dist_sum;

}

int main() {

int32_t n = 4000;

int32_t dist_sum = dijkstra_shortest_path(n, 0);

std::cout<<dist_sum<<std::endl;

return 0;

}

| Compiler/Interpreter |

Execution Time (s) |

System |

Relative |

| LPython |

0.167 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

1.00 |

| Clang++ |

0.993 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

5.95 |

| Python |

3.817 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

22.86 |

| LPython |

0.155 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

1.00 |

| Clang++ |

0.685 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

4.41 |

| Python |

3.437 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

22.17 |

| LPython |

0.324 |

Apple M1 2020 |

1.00 |

| Clang++ |

0.709 |

Apple M1 2020 |

2.19 |

| Python |

3.486 |

Apple M1 2020 |

10.76 |

| LPython |

0.613 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

1.00 |

| g++ |

1.358 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

2.21 |

| Python |

7.365 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

12.01 |

Note the optimization flags furnished to each compiler.

| Compiler/Interpreter |

Optimization flags used |

| LPython |

--fast |

| Clang++ |

-ffast-math -funroll-loops -O3 |

| g++ |

-ffast-math -funroll-loops -O3 |

| Python |

- |

Floyd-Warshall algorithm on array representation of graphs

from lpython import i64, i32

from numpy import empty, int64

def floyd_warshall(size: i32) -> i64:

dist: i64[size, size] = empty((size, size), dtype=int64)

u: i32; v: i32

i: i32; j: i32; k: i32

update: i64 = i64(0)

for u in range(size):

for v in range(size):

dist[u, v] = i64(2147483647)

for u in range(size):

for v in range(size):

if u != v and ((u%2 == 0 and v%2 == 1)

or (u%2 == 1 and v%2 == 0)):

dist[u, v] = i64(u + v)

for v in range(size):

dist[v, v] = i64(0)

update = i64(0)

for k in range(size):

for i in range(size):

for j in range(size):

if dist[i, j] > dist[i, k] + dist[k, j]:

update += dist[i, j] - dist[i, k] - dist[k, j]

dist[i, j] = dist[i, k] + dist[k, j]

return update

print(floyd_warshall(1000))

#include <iostream>

int64_t floyd_warshall(int32_t size) {

int64_t dist[size][size];

int32_t u, v, i, j, k;

int64_t update;

for(u = 0; u < size; u++) {

for(v = 0; v < size; v++) {

dist[u][v] = 2147483647;

}

}

for(u = 0; u < size; u++) {

for(v = 0; v < size; v++) {

if( u != v && ((u%2 == 0 and v%2 == 1)

|| (u%2 == 1 and v%2 == 0)) ) {

dist[u][v] = u + v;

}

}

}

for(v = 0; v < size; v++) {

dist[v][v] = 0;

}

update = 0;

for(k = 0; k < size; k++) {

for(i = 0; i < size; i++) {

for(j = 0; j < size; j++) {

if( dist[i][j] > dist[i][k] + dist[k][j] ) {

update += dist[i][j] - dist[i][k] - dist[k][j];

dist[i][j] = dist[i][k] + dist[k][j];

}

}

}

}

return update;

}

int main() {

std::cout<<(floyd_warshall(1000))<<std::endl;

return 0;

}

| Compiler/Interpreter |

Execution Time (s) |

System |

Relative |

| Clang++ |

0.451 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

1.00 |

| LPython |

0.767 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

1.70 |

| Python |

> 11 |

Apple M1 MBP 2020 |

> 24.39 |

| Clang++ |

0.435 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

1.00 |

| LPython |

0.785 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

1.80 |

| Python |

> 11 |

Apple M1 Pro MBP 2021 |

> 25.28 |

| Clang++ |

0.460 |

Apple M1 2020 |

1.00 |

| LPython |

0.995 |

Apple M1 2020 |

2.16 |

| Python |

> 11 |

Apple M1 2020 |

> 23.91 |

| g++ |

0.695 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

1.00 |

| LPython |

2.933 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

4.22 |

| Python |

440.588 |

AMD Ryzen 5 2500U (Ubuntu 22.04) |

633.94 |

Note the optimization flags furnished to each compiler.

| Compiler/Interpreter |

Optimization flags used |

| LPython |

--fast |

| Clang++ |

-ffast-math -funroll-loops -O3 |

| g++ |

-ffast-math -funroll-loops -O3 |

| Python |

- |

Interoperability with CPython

Next we show that LPython can call functions in CPython libraries. This feature permits “break-out” to Numpy, TensorFlow, PyTorch, and even to matplotlib. The break-outs will run at ordinary (slow) Python speeds, but LPython accelerates the mathematical portions to near maximum speed.

Calling NumPy functions via CPython

main.py

from lpython import i32, f64, i64, pythoncall, Const, TypeVar

from numpy import empty, int32, float64

n_1 = TypeVar("n_1")

n_2 = TypeVar("n_2")

n_3 = TypeVar("n_3")

@pythoncall(module = "util")

def cpython_add(n_1: i32, a: i32[:], b: i32[:]) -> i32[n_1]:

pass

@pythoncall(module = "util")

def cpython_multiply(n_1: i32, n_2: i32, a: f64[:], b: f64[:]) -> f64[n_1, n_2]:

pass

def test_1D():

n: Const[i32] = 500_000

a: i32[n] = empty(n, dtype = int32)

b: i32[n] = empty(n, dtype = int32)

i: i32

for i in range(n):

a[i] = 2 * (i+1) * 13

b[i] = a[i] + 2

sum: i32[n]

sum = cpython_add(500_000, a, b)

for i in range(n):

assert sum[i] == a[i] + b[i]

def test_2D():

n: Const[i32] = 1_000

a: f64[n] = empty([n], dtype = float64)

b: f64[n] = empty([n], dtype = float64)

i: i32; j: i32

for i in range(n):

a[i] = f64(i + 13)

b[i] = i * 2 / (i + 1)

product: f64[n, n]

product = cpython_multiply(1_000, 1_000, a, b)

for i in range(n):

assert product[i] == a[i] * b[i]

def test():

test_1D()

test_2D()

test()

util.py

import numpy as np

def cpython_add(n, a, b):

return np.add(a, b)

def cpython_multiply(n, m, a, b):

return np.multiply(a, b)

(lp) 23:02:55:~/lpython_project % lpython main.py --backend=c --link-numpy

(lp) 23:03:10:~/lpython_project % # Works successfully without any asserts failing

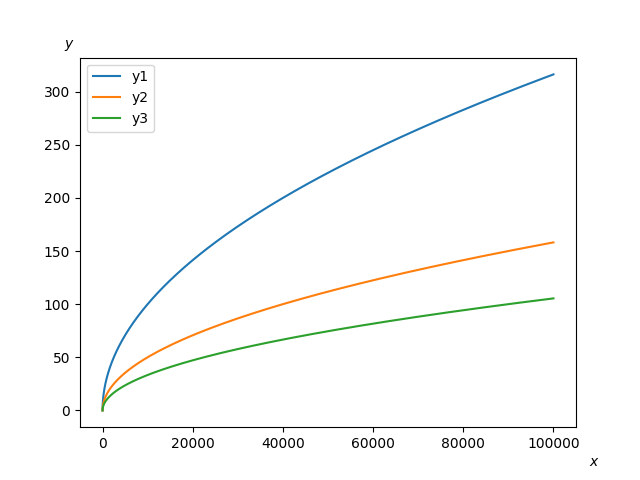

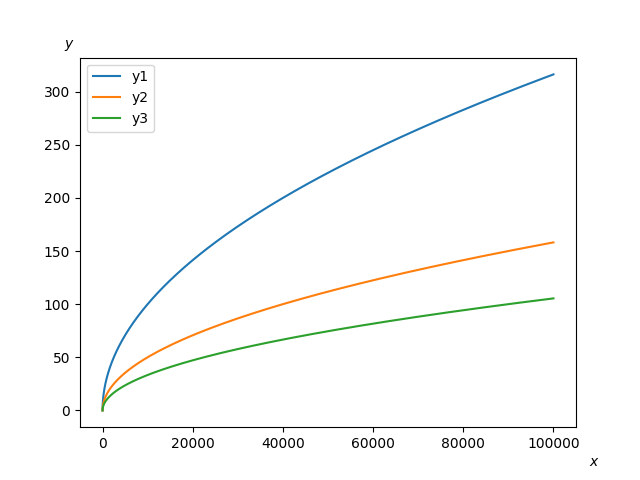

Plotting graphs via Matplotlib

main.py

from lpython import f64, i32, pythoncall, Const

from numpy import empty, float64

@pythoncall(module = "util")

def plot_graph(x: f64[:], y1: f64[:], y2: f64[:], y3: f64[:]):

pass

def f(x: f64, i: f64) -> f64:

return x ** .5 / i

def test():

n: Const[i32] = 100000

x: f64[n] = empty(n, dtype=float64)

y1: f64[n] = empty(n, dtype=float64)

y2: f64[n] = empty(n, dtype=float64)

y3: f64[n] = empty(n, dtype=float64)

i: i32

for i in range(1, n):

x[i] = f64(i)

for i in range(1, n):

y1[i] = f(x[i], 1.)

y2[i] = f(x[i], 2.)

y3[i] = f(x[i], 3.)

plot_graph(x, y1, y2, y3)

test()

util.py

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def plot_graph(x, y1, y2, y3):

plt.figtext(0.92, 0.03, '$x$')

plt.figtext(0.1, 0.9, '$y$')

plt.plot(x, y1, label="y1")

plt.plot(x, y2, label="y2")

plt.plot(x, y3, label="y3")

plt.legend()

plt.savefig('graph.png')

plt.show()

(lp) 23:09:08:~/lpython_project % lpython main.py --backend=c --link-numpy

(lp) 23:10:44:~/lpython_project % # Works see the graph below

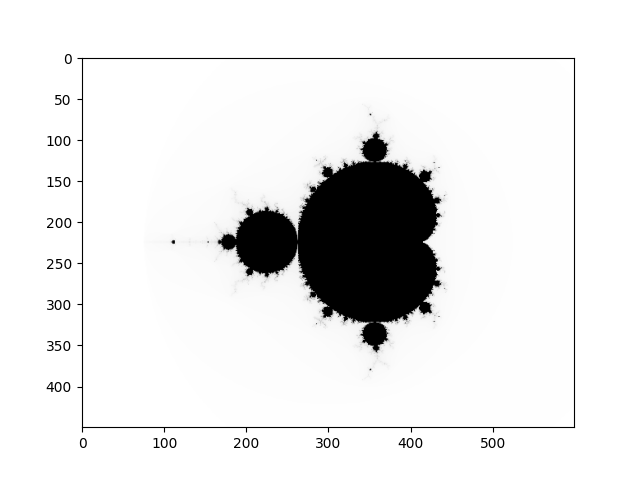

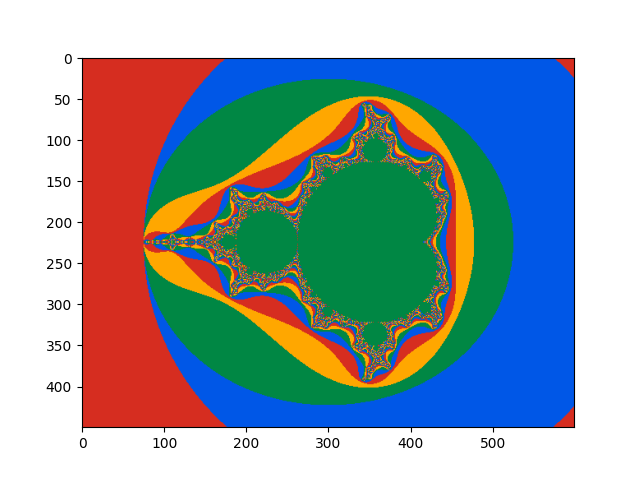

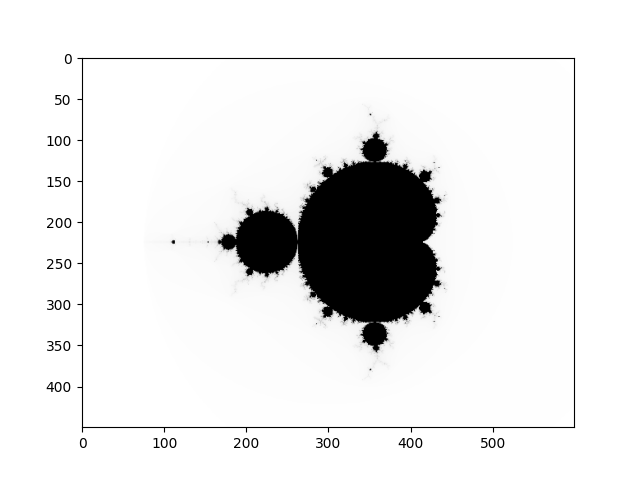

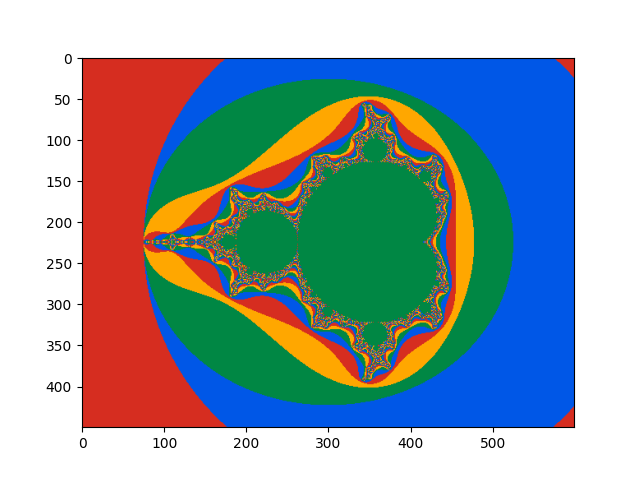

Visualization using Matplotlib: Mandelbrot Set

main.py

from lpython import i32, f64, pythoncall, TypeVar

from numpy import empty, int32

h = TypeVar("h")

w = TypeVar("w")

d = TypeVar("d")

@pythoncall(module="util")

def show_img_gray(w: i32, h: i32, A: i32[h, w]):

pass

@pythoncall(module="util")

def show_img_color(w: i32, h: i32, d: i32, A: i32[h, w, d]):

pass

def main0():

Nx: i32 = 600; Ny: i32 = 450; Nz: i32 = 4; n_max: i32 = 255

xcenter: f64 = f64(-0.5); ycenter: f64 = f64(0.0)

width: f64 = f64(4); height: f64 = f64(3)

dx_di: f64 = width/f64(Nx); dy_dj: f64 = -height/f64(Ny)

x_offset: f64 = xcenter - f64(Nx+1)*dx_di/f64(2.0)

y_offset: f64 = ycenter - f64(Ny+1)*dy_dj/f64(2.0)

i: i32; j: i32; n: i32; idx: i32

x: f64; y: f64; x_0: f64; y_0: f64; x_sqr: f64; y_sqr: f64

image: i32[450, 600] = empty([Ny, Nx], dtype=int32)

image_color: i32[450, 600, 4] = empty([Ny, Nx, Nz], dtype=int32)

palette: i32[4, 3] = empty([4, 3], dtype=int32)

for j in range(Ny):

y_0 = y_offset + dy_dj * f64(j + 1)

for i in range(Nx):

x_0 = x_offset + dx_di * f64(i + 1)

x = 0.0; y = 0.0; n = 0

while(True):

x_sqr = x ** 2.0

y_sqr = y ** 2.0

if (x_sqr + y_sqr > f64(4) or n == n_max):

image[j,i] = 255 - n

break

y = y_0 + f64(2.0) * x * y

x = x_0 + x_sqr - y_sqr

n = n + 1

palette[0,0] = 0; palette[0,1] = 135; palette[0,2] = 68

palette[1,0] = 0; palette[1,1] = 87; palette[1,2] = 231

palette[2,0] = 214; palette[2,1] = 45; palette[2,2] = 32

palette[3,0] = 255; palette[3,1] = 167; palette[3,2] = 0

for j in range(Ny):

for i in range(Nx):

idx = image[j,i] - i32(image[j,i]/4)*4

image_color[j,i,0] = palette[idx,0] # Red

image_color[j,i,1] = palette[idx,1] # Green

image_color[j,i,2] = palette[idx,2] # Blue

image_color[j,i,3] = 255 # Alpha

show_img_gray(Nx, Ny, image)

show_img_color(Nx, Ny, Nz, image_color)

print("Done.")

main0()

util.py

def show_img_gray(w, h, A):

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

plt.imshow(A, cmap='gray')

plt.show()

plt.close()

def show_img_color(w, h, d, A):

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

plt.imshow(A)

plt.show()

plt.close()

$ ls

main.py util.py

$ lpython main.py --backend=c --link-numpy

Done.

Conclusion

The benchmarks support the claim that LPython is competitive with its competitors in all features it offers. In JIT, the execution times of LPython-compiled functions are at least as short as equivalent Numba functions. The speed of JIT compilation, itself, is slow in some cases because it currently depends on a C compiler to generate optimal binary code. For algorithms with rich data structures like dict (hash maps) and list, LPython shows much faster speed than Numba. In AoT compilation for tasks like the Dijkstra algorithm, LPython beats equivalent C++ code very comfortably. For an array-based implementation of the Floyd-Warshall algorithm, LPython generates code almost as fast as C++ does.

The main takeaway is that LPython/LFortran generate fast code by default. Our benchmarks show that it’s straightforward to write high-speed LPython code. We hope to raise expectations that LPython output will be in general at least as fast as the equivalent C++ code. Users love Python because of its many productivity advantages: great tooling, easy syntax, and rich data structures like lists, dicts, sets, and arrays. Because any LPython program is also an ordinary Python program, all the tools – debuggers and profilers, for instance – just work. Then, LPython delivers run-time speeds, even with rich data structures at least as short as alternatives in most cases.