Author's Note: This full-length excerpt comes from Beneath a Starless Sky, a Shacknews Long Read that explores the making of Obsidian Entertainment's Pillars of Eternity franchise and classic RPGs such as Baldur's Gate, Planescape: Torment, and Fallout 1 and 2. You can read Shacknews Long Reads for free right here at Shacknews, download them as epubs by subscribing to Shacknews Mercury for as little as $1 per month, or--in a limited exclusive--purchase StoryBundle's Fall Ball Game bundle, which includes Beneath a Starless Sky and eight more DRM-free ebooks about game development and culture. We're incredibly proud of what Shacknews Long Reads bring to games journalism, and hope you enjoy this feature and many more. -David L. Craddock, Shacknews Long Reads Editor

War. War never changes. Neither do the fundamentals of game development.

In March 2015, Obsidian released Pillars of Eternity as a love letter to the lineage of Infinity Engine roleplaying games of the late ‘90s and early 2000s. Technically, Fallout and its sequel do not belong in that lineage, but the post-apocalyptic franchise’s influence on Baldur’s Gate and its ilk is inarguable. Many developers who worked on Baldur's Gate, Planescape: Torment, Icewind Dale, and Pillars of Eternity had worked on Fallout and Fallout 2 first, bringing what they learned to bear on those later projects.

That makes the Fallout games distant relations of the Infinity Engine RPGs, and worthy of closer examination. What follows is an oral history straight from the mouths of several of the pioneers who entered a veritable wasteland of computer RPG (CRPG) development and made that fallow ground fertile once again.

By Gamers, For Gamers

Brian Fargo founded Interplay Productions on the foundation of a simple yet powerful creed: That the people he hired should be as passionate about making games as they were about playing them.

Background, experience, accolades—none of those mattered in Interplay’s early, most humble days. Fargo created a workplace that blurred the line between office and home. Anyone who wasn’t writing code or pushing pixels could be found holed up in an office or in an open area playing a board game. Interplay’s culture was a siren’s song answered by developers who, like Fargo, were eager to make their mark.

BRIAN FARGO [founder of Interplay Productions]

When I was in junior high school, they had a mainframe computer. People talk about the cloud now, but everything was in "the cloud" back then. You just had a dumb terminal talking to a mainframe. I was fascinated by computers even though there wasn't much in terms of games. The coin-op business had just gotten to the point where games like Pong and Space Invaders were emerging, and it was those games that first got me interested.

Then my parents got me an Apple II in high school, and that really opened my eyes to how you can make games, how I could go beyond just playing them. I played a lot of the older titles. I remember there were some old strategy titles where you would make a move and the computer would take two to three hours to process its turn. You'd go crazy when a game crashed halfway through because that meant you just lost three days of playing.

So I really discovered games through those means. I always had a background in reading a lot of fiction: comics, Heavy Metal magazine. Playing Dungeons & Dragons was a big part of high school for me. But the thing that I think led me to create games, which I think most people would give the same answer to, was, I looked at what was out there and thought, You know, I could do better. That's what sent me down my course.

CHRIS TAYLOR [designer at Interplay, lead designer on Fallout]

I met some people working at Egghead Software who played Dungeons & Dragons. I was looking for a roleplaying game, so I hooked up with them to play. One of the players worked for Interplay. After a few months, he told me they had a job opening, so I went down and applied.

BRIAN FARGO

One of my high school buddies was Michael Cranford. His parents wouldn't get him a computer, so he used to borrow mine. We made this little adventure game. I'd give him the computer over the weekend, he'd write code for a section, then he'd give it back and I'd try to finish his section and do my part, then he'd go through mine. We'd go back and forth. We did this all summer. We made this little game called the Labyrinth of Martagon. We actually put it in some baggies and probably sold five copies. That would be a very obscure, technically speaking, first game. But one that really got into distribution would be The Demon's Forge.

I was a big fan of adventure games. I loved all the [adventure games developed by] Scott Adams, all the Sierra adventures. I also liked Ultima and Wizardry, but from a coding perspective I wasn't strong enough to do that stuff, but I thought I could do an adventure game. It was a category I liked, and I liked medieval settings. As far as attracting attention, I had a budget of $5,000 for everything. My one ad in Soft Talk [magazine] cost me about 2,500 bucks, so 50 percent of my money went into a single ad.

One of the things I did was I would call retailers on a different phone and say, "Hey, I'm trying to find this game called Demon's Forge. Do you guys have a copy?" They said, "No," and I said, "Oh, I just saw it in Soft Talk. It looks good. They said, "We'll look into it." A few minutes later my other line would ring and the retailer would place an order. That was my guerrilla marketing. I was selling to individual chains of stores. There were two distributors at the time that would help you get into the mom-and-pop places. It was a store-by-store, shelf-by-shelf fight.

CHRIS TAYLOR

I interviewed well, I guess—well enough—and I beat out one other guy because I had a pickup truck, and they needed someone to take packages and stuff like that. So, I got the job because of my pickup truck and my love for D&D. I started in customer service and technical support.

BRIAN FARGO

There were some Stanford graduates who wanted to get into the video game industry, and they bought my company [Saber Software]. They paid off my debt and I made a few bucks, nothing much to brag about. They made me the vice president and I started doing work for them. It became one of those things where there were too many chiefs and not enough Indians, and I was doing all the work. I was with them for about a year when I quit and started Interplay in order to do things my way. I'd gotten used to running development, so that seemed like the next natural step.

With Interplay, I wanted to take [development] beyond one- or two-man teams. That sounds like an obvious idea now, but to hire an artist to do the art, a musician to do the music, a writer to do the writing, all opposed as just the one man show doing everything, was novel. Even with Demon's Forge, I had my buddy Michael do all the art, but I had to trace it all in and put it in the computer, and that lost a certain something. And because I didn't know a musician or sound guy, it had no music or sound. I did the writing, but I don't think that's my strong point. So really, [Interplay was] set up to say, "Let's take a team approach and bring in specialists."

FEARGUS URQUHART [producer at Interplay Productions, co-founder of Obsidian Entertainment]

Eric DeMilt and I went to high school together. We met when we were freshmen. It turned out Eric was a computer gamer. He had a Commodore 64, like I did, and he would play roleplaying games and stuff like that, but he wasn't as much of what we'd call the hot RPG scene of Tustin High in 1984. I mean, you know... girls. Yes.

ERIC DeMILT [producer at Interplay Productions and Obsidian Entertainment]

Feargus and I met in 1984, so I've known him for thirty-four years. I've known one of our testers here [at Obsidian] since the first grade, and my first memory of him involves Doug [QA tester at Obsidian] and a guy in a Darth Vader silverware. Anyway.

Feargus and I would write and read comic books, play games together. I think the first PC game I ever got super hooked on was a game called Wasteland which, as it turned out, was developed by Interplay Productions. Fast forward a few years, and Feargus was at University of California, Riverside, I think, and was coming back on holidays and weekends. We were still friends, and he'd gotten a job through another high school friend of ours at Interplay Productions as a tester.

I'm like, "Seriously? They'll pay you to test games?" It was super-nerdy stuff. They had the Lord of the Rings license. They were doing Battle Chess [games]. They had the Star Trek: 25th Anniversary license at the time, so it was nerd heaven for me. I said, "Dude, get me a job." That was in '92 or so.

FEARGUS URQUHART

I met a lot of people who I still know to this day and hang out with: Chris Taylor, who ended up being lead designer on Fallout; Chris Benson, who runs our IT here at Obsidian. I got a job at Interplay through Chris Taylor as a tester. Chris, Eric, and my other friend, Steve, were like, "We want to be testers." They needed testers, so I said, "Hey, these two guys are looking for jobs." They said they needed more people, so they got hired. I think that was in '92, which was the second year I was a tester.

BRIAN FARGO

I had a lot of diverse friends. I was big into track and field, I played football, so I had those friends, then I had friends from the chess club, the programming club, and a Dungeons & Dragons club. Michael [Cranford] was from that side. I always thought he was a pretty bright guy and one of the better dungeon masters. We played a lot of Dungeons & Dragons. We always tried to focus on setting up dungeons that would test people's character as opposed to just making them fight bigger and [tougher] monsters. We'd do things like separate the party and have one half just getting slaughtered by a bunch of vampires and see who would jump in to help them. But it wasn't really happening. It was all an illusion, but we'd test them.

I always got a kick out of the more mental side of things, and Michael was a pretty decent artist, a pretty good writer. He was my Dungeons & Dragons buddy, but then he went off to Berkeley, and I started [Interplay]. He did a product for Human Engineering Software, but then I said, "Hey, let's do a Dungeons & Dragons-style title together. Wouldn't that be great?" That's really how the game came about. He moved back down to Southern California, and I think we actually started when he was still up north. But then we worked on Bard's Tale together, kind of bringing back the Dungeons & Dragons experiences we both enjoyed in high school.

ERIC DeMILT

I started part-time as a tester, testing Game Boy games and PC games. The industry was in its infancy. The company that would go on to become Blizzard was a sub-contractor of Interplay’s [called Silicon & Synapse]. I would come in, and there'd be a build of some random game on a PC with a sheet of paper telling me what to do. I'd break the game and leave a sheet of paper with notes for my boss, who I'd see once or twice a week.

It was the wild west.

SCOTT EVERTS [technical designer at Interplay Productions and Obsidian Entertainment]

I originally wanted to get into the TV-and-movie-effects field. I went to Cal State Fullerton and got a degree in radio, TV, and film, with a focus on film. I did a little bit of Hollywood stuff. I was a production intern on MacGyver during Season 6, and [almost] got a job as a production assistant on Star Trek: The Next Generation, Season 4. I was the third choice out of two. That was in 1991. I had a bunch of friends who worked at Interplay Productions. I worked at a software store and was [almost ready to] graduate. I said, "I don't want to work in software. I want to find something else."

A friend of mine said, "We're doing a Star Trek computer game. Do you want to come and play-test it?" I said, "Okay!" I went over, and I knew about half a dozen people who worked at Interplay, and there were only forty or so people there. I used to play D&D with them and video games with them; we had our little group. I went over there as a QA guy and worked on Star Trek: 25th Anniversary. CD-ROM was becoming a thing, so we did a CD-ROM version, and they needed a designer to flesh out some scenarios.

ROB NESLER [art director, Interplay Productions and Obsidian Entertainment]

When I was fourteen or fifteen, for some reason I had a Popular Science magazine with an article about home computers. I must have read that article a dozen times, dreaming about computers. They had little screenshots of games, and that started me on my way. From then on, I thought, I want to be able to draw on a computer.

I got a TRS-80 model three a year or so later, which had pixels the size of corn kernels. I immediately tried to figure out how to program on it with the goal of drawing lines and circles, making houses, spaceships, dragons.

TIM CAIN [lead programmer on Fallout, co-game director at Obsidian Entertainment]

I started playing Dungeons & Dragons when I was fourteen. My mom actually got me into it. She worked at an office in D.C. with a bunch of Navy admirals and stuff. A few of the "boys" played Dungeons & Dragons, so we went over to their house one weekend and played it, and I really got into it. She had five kids; I was the youngest. When we turned sixteen, she would give us a few hundred dollars and say, "You can buy whatever you want." I bought an Atari 800 and taught myself how to code. I got a job at a game company that was making a bridge game for Electronic Arts when I was sixteen. That's how I got into games, but I really wanted to make RPGs.

Some of my friends had an Apple II. I thought it was really amazing. The Atari 400 and 800 had way better graphics. They were way better than the Apple II, and they were also way better than PCs at the time. Part of the reason I got my job at that game company was because I knew all the graphics modes, especially all of these undocumented, special graphics modes called the Plus Threes: if you added +3 to a graphics mode, it would [display] without a text window at the bottom. This company was making games for a cable company, and they needed an art tool written. Their resolution was too high for a PC at the time, but an Atari 800 could just do it. None of their programmers knew it.

BRIAN FARGO

I found the original design document for Bard's Tale, and it wasn't even called Bard's Tale. It was called Shadow Snare. The direction wasn't different, but maybe the bard ended up getting tuned up a bit. One of the people there who has gone on to great success, Bing Gordon, was our marketing guy on that. He very much jumped on the bard [character] aspect of it.

At the time, the gold standard was Wizardry for that type of game. There was Ultima, but that was a different experience, a top-down view, and not really as party based. Sir-Tech was kind of saying, "Who needs color? Who needs music? Who needs sound effects?" But my attitude was, "We want to find a way to use all those things. What better than to have a main character who uses music as part of who he is?"5

LEONARD BOYARSKY [art director on Fallout, co-game director at Obsidian Entertainment]

I think when you're five years old, everyone loves to draw. Most people give it up. I never did.

SCOTT EVERTS

I moved from QA to design and helped on the CD-ROM version. It had a short scenario at the end that we expanded. I did some production work [after that]. I worked on Star Trek: Academy, and several [products] that never got finished. We were going to do Star Trek: Battle Chess, just Battle Chess with a Star Trek theme. That one got cancelled because it was really expensive; the artwork was costing a lot of money.

We were also going to do a Stark Trek chess game with a 3D chess board, but we didn't do it because no one could figure out how to play it. There were no rules for it. It was just a visual thing for TV shows. Some fans made rules, and we found out it was impossible to play. I know there are real rules now, but at the time we decided [to table it].

LEONARD BOYARSKY

I had this crazy idea that I was going to be an artist, and I never wavered from that. I pursued that all through school, and then I was having trouble getting work as a freelance illustrator at the time. That's how I found my way into the videogame industry. I was just looking for work until my illustration career took off. It didn't quite work out.

A bunch of people I went to school with were a semester ahead of me, and they were all hired by Buena Vista Software, which was a new division that Disney was starting to try and do something a little different. I was having trouble getting work, I called one of my friends who had that job and said, "Are there any jobs there?" Basically, they were freelance, but they were freelance directly for [Disney]. But there was this other project they were doing through Quicksilver Software that they hired me to work on, because I went up and I showed the art director my portfolio. I had only ever worked on Macs before, except for a basic class I'd taken in high school. So, I had no idea how to do anything on PC at that point.

That project lasted about two and a half months, I think, before it got cancelled.

TIM CAIN

One of the programmers they'd hired was a friend of mine who was three years older and had already graduated high school. He gave them my name. I just came in for an afternoon, and this was before I had a driver's license. I think my mother had to drive me out there. In a two-hour session I coded up a basic framework for the art tool they needed. You used a joystick that you plugged into the front of the Atari 800. They had an artist come in, and he said, "Yeah, I can use this, but there are a whole bunch of other features I need." I said, "Well, I can't do that right now." They asked me if I could start working after school. I did that two or three days a week. I'd do that two or three days a week, and then I'd drive there. I'd drive along the Beltway, which was crazy. My junior and senior year, two or three days a week, I'd drive out there after school.

The bridge game paid for college. I was in Virginia, and I came out here to California to go to graduate school. A few years into that, I didn't like it. I sent my resume out, and Interplay was literally three or four miles away. They were making the Bard's Tale Construction Set. I found out later that [the job was between] me and someone else, and I got the job because I had worked on a game before, and because I knew the Dungeons & Dragons rules. The questions came down to, they asked us both what THAC0 was, and the other programmer didn't know.

ROB NESLER

Some years later, I graduated high school and went into college as a graphic design major, thinking I would be able to do some illustrations on computers there. The school did not have any, so I found a program outside of the school to learn how to make art on a computer. They had some Apple Macintosh IIs, which had 19-inch displays and 256 colors. That's when I started to make art. It was graphic design, but the computer did have a 3D program that I got to play with. I built some spaceships in 3D.

From there I got a job working for an ad agency but didn't really enjoy doing logos and ads for perfumes, lady's shoes, and stuff like that, so I got a job working for CompUSA. I worked in the software department selling software. On the backs of game [boxes] in those days, the late '80s, all the publishers put their addresses on the backs of boxes. The publishers were often the developers, and I just started sending artwork to whoever would open up the envelope.

Eventually somebody at Interplay got my work. It was color bitmaps of space scenes, of robot tanks fighting, of warriors riding winged beasts, that kind of stuff. I think I had a vampire in there as well. That was all it took back then.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

Buena Vista had another project on the line, which was called Unnatural Selection. We ended up cutting out claymation dinosaurs, or stop-motion, clay dinosaurs out of backgrounds. It was a really cool little project. I ended up working with one other guy on it. I'd just go to this guy's house in L.A., and we'd work in a little studio he had there.

After that was done, the thing I missed was that when I was working for Quicksilver, most of the stuff they did was for Interplay, but for some reason they had this other project that I got put on that they were doing for Buena Vista. So, through them, I had a couple of interactions with the art director at Interplay. I called him up when I couldn't find work after Unnatural Selection.

When I got hired at Interplay, I was working under the direction of Rob Nesler, who's the art director at Obsidian now. I did a month's work of work in a week, I think, so he started giving me different things to do. Eventually, I worked my way up from being a grunt artist to being a lead artist on Stonekeep. That morphed into being the art director on Fallout.

Work. Play. At Interplay, it was impossible to tell where one ended and the other began. Developers channeled their passion for gaming into their creations, and conducted that excitement back into their favorite hobby.

ROB NESLER

It was a little bit like the wild west, though not as bad as what you've heard about Atari. It was a little more conservative than that, but we still had our fun.

CHRIS TAYLOR

I came in right at an expansion time where they staffed up heavily and took on a bunch more projects. I was a kid still making my way through college. I'd worked a couple of hourly job, so for me, this was the coolest thing in the world.

We did things together. We didn't go home. We stayed until 2:00 a.m. in the morning playing games, talking games. It all revolved around games. It was a very exciting time.

TIM CAIN

When I started, I was employee forty-two. It was a very small company. They had that logo: "By Gamers, For Gamers." It was really true. Everybody there played video games. Fargo played games. People would go home at night to play games, or sometimes you'd just say there. You'd work all day, and then you'd go to the conference room to see if anybody had a board game out.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

I was just happy to be working as an artist. I had played Zork and Wizardry. I thought those games were really fantastic because you had so much imagination involved. You would buy into the games. You could easily look at Wizardry, for example, and say, "These are just hallways drawn with simple lines. What is this? This is nothing," you know? But if you bought into it and imagined you were playing D&D, it was this really fun thing.

CHRIS TAYLOR

There were a lot of people at the office who were into Bomberman, so we'd have Bomberman nights. We'd have Atari Lynx nights.

TIM CAIN

The Atari Lynx came out, if you remember the little handheld Atari console. It was like a Switch back in '92. So many people there bought Lynxes that we would have waiting lists for people. We'd say, "We're going to start this eight-player game, then after an hour these other people can join in." It was just wonderful. Everybody there was a gamer, so it was a great place to work.

CHRIS TAYLOR

We played a lot of multiplayer games, and Tim [Cain] was definitely part of that crowd, and people like Scott Everts, all these people who ended up working on Fallout. We played games together and were all friends with each other, so it was natural for us to get together and talk.

TIM DONLEY [artist, Interplay Productions and Black Isle Studios]

It was a very loud, fun place. People wandered in at all times of the day. By five or six o'clock, someone would say, “We're going to play Descent 2. Everybody get on the LAN.” We'd all log in and start up a bunch of games and play for hours.

We had one giant room where we could all gather. It was called the rec room. I was considered quite loud. I would laugh loudly and make all this noise. Every day at six o'clock we'd play XMEN Vs. Street Fighter, or some of us would play Quake. I would scream so loud that people from the other side of the building would walk in and go, “Is that Tim? He's so freaking loud I can hear him through the walls.”

CHRIS PARKER [producer, Interplay Productions and Black Isle Studios; co-founder, Obsidian Entertainment]

It was a really fun environment. You're talking about a company where the average age was probably around twenty-seven or something like that; it was really, really young. People like Brian Fargo were... I think he was forty, and he seemed ancient to me.

I say that and I'm going to be forty-six in a couple of days.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

It was really relaxed. It was a very small, though I didn't think of it as very small at the time, but looking back on it, it was. I was employee number eight-eight or something like that. I was just amazed that people were paying us to come in there and do this stuff. The job I had was a little bit of a grind because it was just cutting stuff out of backgrounds, but I was really happy to have a job.

Once I got to start doing real artwork, it was extremely thrilling. But the early Interplay had this really creative, non-corporate, just excitement about making games to it.

CHRIS TAYLOR

One time when I was working on the Lord of the Rings game for Super Nintendo, they needed someone to play the orc. I dressed in underwear and ran around with a trashcan lid as a shield, and a toy sword. They took photographs of me walking and running up and down the corridor, swinging my sword.

I got the negatives, and I destroyed them, because there was no way. There might have been some tequila involved. Perhaps. I can't quite remember the fact. No, those photographs will never see the light of day.

TIM DONLEY

For that period, the '90s of Interplay, it was such a fun experience. Interplay felt like it was a family: A bunch of people who knew and liked each other. Whether I was under Brian Fargo, or Feargus, or whoever the management was, they just expected and encouraged a lot of game playing.

Designing games made by gamers was one of Brian Fargo’s founding pillars. Another was to diversify . Historically, programmers had done it all: written code, pushed pixels, programmed in music notes, produced and shipped product. Fargo aimed to create and then fill more specialized roles to facilitate better development.

SCOTT EVERTS

Interplay had programmers, designers, and artists, but "designer" was an all-encompassing thing. Sometimes we would do scripting, and there weren't scripters. When I was working on Star Trek for Super Nintendo, we were doing scripting. We had a scripting language, and we were writing code in the scripting language to make the missions work. Sometimes we straddled programming a bit, although we did eventually hire scripters.

FEARGUS URQUHART

I never actually asked the people who promoted us out of testing why they did [made us producers]. I think that we were more organized, and had more of an ability to communicate. We were pretty good at communication, and we were pretty organized, and a lot of the reason why we went out of QA and became producers was because people vouched for us and said, "They're good guys."

CHRIS PARKER

I was twenty-four, twenty-five, and I've been made an associate producer. I've been given responsibility over titles that cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. I barely know what I'm doing, yet I'm telling developers what they should be doing.

That was actually quite common. If you were a warm body and knew how to use a computer, you could get a job in the videogame industry doing something.

CHRIS TAYLOR

There's a lot of different types of designers, and we've become a lot more formal about it. At the time at Interplay, a designer was someone who wasn't a programmer or an artist, but who helped make the game. I wrote dialogue, I laid out maps on paper that artists would then convert into actual levels. I designed characters and systems.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

It was this transition period where you had to know something about art. You could do all this stuff with it that you couldn't do before, and I felt like I had a lot of knowledge and experience, even just from stuff I'd learned at school, that I could bring to it, but I was relegated to this grunt position of cutting things out of backgrounds. I worked really hard at it, and part of my incentive was, "If I get through cutting all these characters out, I'm getting something else to do."

Once I'd done all the characters, at least as many as I knew of at the time, they came back to me and they said, "Um, we made a mistake. We did these wrong. We have to redo all of them." I said, "I did everything I was supposed to do." They said, "Yeah, it was our fault, completely, 100 percent, but you have to redo them." That just frustrated me to no end. I went home after work and I started a new portfolio. I was like, "I have to get out of here. I can't do this anymore." I made a bunch of paintings and started shopping them around, and I was unsuccessful, luckily.

SCOTT EVERTS

On Star Trek: 25th Anniversary, I think I was credited as an assistant or junior designer because we were writing dialogue in QA. A lot of the scripts were written by out-of-house people, and they didn't encompass all situations. Since I was incredibly familiar with Star Trek... One of the reasons I got hired was because I had the entire original series on Laserdisc. I brought my set in so people could watch it. We'd sit around and watch Star Trek episodes, and I got pretty good at writing dialogue for [the game] because I was such a Star Trek geek. I knew the material and characters so well.

One of the things I did on Star Trek: Judgment Rites was I became the liaison to Paramount Pictures, which was frustrating because I felt like I knew more about Star Trek than they did. Sometimes we'd get into... Well, I wouldn't get into arguments because you couldn't really argue with whatever they said. I would disagree with some of their conclusions, things they wanted to change.

ROB NESLER

My first game that I got to work on the Bard's Tale Construction Set. I created artwork for all the dungeons and, ultimately, all the monster-encounter portraits as well. On RPM Racing, I did the tile sets, and Jay Patel, one of the programmers, and I came up with a mechanism for capturing cars so that we could create in-game models. We'd put models of cars into this little armature and take some pictures with a video camera.

David Mosher was an artist involved in welding the armature together. We captured footage of a whole bunch of cars, and a whole bunch of other artists and I hand-edited them until they looked okay.

One of the guys said, "You know, I could have just drawn all these." He might have been exaggerating. We were always optimistic about how easy it would be for us to get something done once we'd done it.

ERIC DeMILT

One of the producers came to me one day and said, "Hey, I need an assistant. You wanna do this job?" I said, "All right, I'm in. That's super cool." That involved rotoscoping [models] for games like Clay Fighter. We were doing super-early, super-ghetto chroma key for Stonekeep: taking live actors and depositing them into scenes.

We were working out how to do all that. It was super home brew.

FEARGUS URQUHART

How do you submit a Super Nintendo game? You learn. Basically, "Here's a big packet, here's a checklist. Go figure it out." I think what it was, was I liked everything about making games. If there was anything I could have become, it would have been a programmer, but I was just interested in games as a whole. I liked having the ability to do whatever, and back then as a producer, you could do whatever.

CHRIS TAYLOR

One of the first big games I worked on was Stonekeep, and we needed to know how the game needed to react when a player swung the sword. One of my jobs was deciding, "This is how much damage a sword does, and here's a bunch of swords, and here's all the stats and skills that go into sword swings." I also did data entry. I did the timing for certain animations and sound effects.

SCOTT EVERTS

Eventually my title became "technical designer." That meant I was an in-between for art and design. I would do some of the basic art. One thing I did on Fallout and Fallout 2, more so, was little pieces of art for junctions. Like, "We need this corner." I'd go into Photoshop, and everything was sprites, so I'd take two pieces, join them together, clean them up, and make a new [corner] piece. They might say, "We need a different corner here," or "We need this piece flipped." I would do light artwork.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

I did a lot of inventory art, just stuff here and there. Then we had these 3D machines, SGI machines, that were running this [software] called PowerAnimator, which was the precursor to Maya. Interplay, in its infinite wisdom, had spent around $30,000 per machine. Or maybe it was $30,000 for the software.

They spent all this money on machines and software, and then they realized that the only people who knew how to use those machines and that software worked in the film industry, and they were making a lot more than artists in the games industry were making at that time. We had these machines sitting in this room, that no one was using. I was so frustrated that I started coming in after work and I taught myself how to use the 3D software.

There was no Internet, no YouTube help at the time. It was me, in a room. We didn't have Internet at Interplay at the time. It was me, in a room, with these manuals, trying to make heads or tails out of what I was going to do and how I was going to make it.

ERIC DeMILT

The first Interplay logo was made before 3D programs had particle systems, so we actually lit a sparkler, videotaped it, then cut out the frames of the sparkler's particles. If you look at an old-school Interplay game, there's a piece of marble that flies through space, and this laser etches the Interplay logo into it. That was a piece of marble left over from Brian Fargo's mansion remodel or something. He brought in a piece of green marble and said, "I want to laser-cut things into this."

So, I held a sparkler in my hand and videotaped it, and we had to cut out every particle. Then we got a 3D programmer who did the laser-and-molten-gold effect.

ROB NESLER

When we worked on the [Super] Nintendo games, there was this editor, and it was horrible. You had to create a palette, and creating that palette involved a lot of entering RGB [red-green-blue] values initially. Then you had special rules, such as the tile size, and the tool was per-pixel editing. There was no brush [to paint wide swathes of pixels]. It was torture to build a tile set with that program.

I look back on that and remember that we were so stuck on Deluxe Paint and Deluxe Paint Animator for DOS. Those were our tools. The idea of using a workstation with 3D software on it hadn't yet occurred to us, even though I had used it before on another company, but that was on a Mac and we [Interplay] did use Macs.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

I made a little character as a proof of concept, to show that I could do it. They said, "Okay, you can make this tentacle temple creature for the game." I designed it myself. I started from scratch again. I became this 3D artist who did a bunch of characters, did some scenery work. I kept doing some of the pixel stuff, and every now and then I had to go back and cut out some more creatures.

FEARGUS URQUHART

On Shattered Steel, which was the first game I worked on with BioWare, I wrote the VO [voiceover] script. I mean, who am I to write a VO script for a game? A stupid, twenty-five-year-old without a college degree? But that's what I liked about being a producer. I liked being involved with how it was all going to come together, putting that puzzle together.

CHRIS TAYLOR

It was really a team effort. I was just happy making games. If they said, "Hey, we need someone to enter all these stats," well, sure, I'll sit down and do that. That seems okay to me.

ROB NESLER

As the company grew, your knowledge of all the people and the processes elevated you into a leadership position almost naturally. I was an artist for a few years, but I think maybe in the case of Interplay, there was some growth that happened pretty quickly, and perhaps I was advanced into the art director leadership position a little quicker in an effort to meet those growth needs.

CHRIS PARKER

A lot of those people didn't really know what the heck they were doing, or why. That resulted in a lot of things that were really well-organized and smartly done, but also in things that were chaotic. You kind of had to—very intelligently and in a politically nice way—push your agenda through. If you were really smart about it, and you could do that, you could get a lot of stuff done.

ERIC DeMILT

I think the ability to make decisions quickly without an obvious right answer [in sight] is important. A lot of what we do is invent new things: new systems, new content, new techniques for making that content. It's easy to get bogged down and paralyzed. "Do we need this new thing?" Sometimes there's no right answer, and maybe it would make the project ten percent better, or maybe it wouldn't. You've got a lot of super-smart people: brilliant designers who are passionate about what they're doing, talented programmers who can tell you technically why A or B should or should not happen.

You've got to be able to take all of that and, while knowing less than they do about any particular subject, be willing to make a decision just to move things forward.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

I had started work on Fallout with Tim. There's a weird gray area there, because I feel like I'd been assigned to Tim's project but hadn't actually started working on it. Then I saw the credits with Stonekeep, when I was working on the intro movie. I saw the credits, and found out I was now a lead artist. I was like, "Great. I'm a lead artist."

I went from there to be the lead artist on Fallout, and I felt like I was doing much more than art directing. I was almost a creative director on there. So, I just promoted myself. No one at Interplay ever said, "Yes, you're the art director," or "You can be the art director." No one ever said anything, so that's how I became an art director on Fallout.

After Hours

At five p.m., office drones punch a clock and head home. Interplay’s developers left the office as well, but only to grab a bite to eat. Those in the middle of crunch—an industry term for overtime in order to meet a project deadline—came back to work through the night. Most of their peers joined them, but not to work. They were there to throw dice.

ERIC DeMILT

Tim and I are good friends. A bunch of us would go over to his house and play Wiz-War, so we were always talking about different games. Wiz-War was this cool Steve Jackson tabletop game. It's fun! Look it up. Play it.

TIM CAIN

When I was at UCI [University of California, Irvine], I used to introduce grad students to different gaming systems. We played Dungeons & Dragons, Torg, GURPS, Spelljammers, a bunch of different things. I got to Interplay and was really excited because there were a bunch of people there who wanted to play. I didn't even have to ask. Someone said, "Yeah, if you want to run any game sessions, we're looking [game masters]."

Everyone wanted to play, no one wanted to run. They were looking for basically DM-type people. So, I started running GURPS sessions after hours.

CHRIS PARKER

There were social events you could do on any given night of the week. There were tons of games happening all over the company, Dungeons & Dragons games and stuff like that. It was a really work-hard-play-hard environment.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

I think it was the first Advanced D&D, if not the original D&D. The reason I don't know is because I had the box and I had all this stuff, but I didn't know anybody who played D&D.

TIM CAIN

I liked GURPS because it was generic. We could play whatever genre we wanted. We tried a whole bunch of different things. We tried GURPS in space, we played GURPS time travel. We did one called GURPS Everything, where I said, "You can make a character using any abilities from any book you want." That was a crazy, crazy session.

The storyline was a bunch of people attending a funeral. So, nobody knew anybody. The players didn't know each other, and they didn't know who died. They just got an invitation: "Hey, this person named you in their will so you have to show up." We had people using GURPS psionics, GURPS high-tech, GURPS space. There was one person there who made their character literally insane. They were literally insane. They thought they were a time traveler and they weren't. They were an escaped mental patient.

We had so much fun with that game because nobody knew where it was going to go, where it could go. Then we tried another one called GURPS Nothing, where I said, "You can't use anything. No supplements. Just use the basic set." That was fun, too.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

I tried to get my friends to play. We'd read all the instructions, and you can't start playing D&D that way. You need to learn the game from somebody who's actually played. We'd spend days making characters and then we'd die within five minutes.

We said, "This sucks. We don't know how to do this."

TIM CAIN

I made a little dungeon once: it was six, seven rooms. I would play a different group through it every night. It was in GURPS Conan. Every group had a completely different experience in it. One group never made it past the second room. They started in-fighting and killed themselves.

Another group made it out, but they had to sacrifice one of their people to do so. Basically, a monster was bearing down on all of them, and they're like, "Well, if we let it catch Scottie [Everts], maybe it'll stop to eat him and the rest of us can make it out." That's what they did. Other groups had this big battle with it and they died; others had a big battle, and they lived. It was this really amazing thing.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

I went to Interplay and started playing GURPS with Tim and some of the other people who ended up on the Fallout team. Tim was the GM. That was my first experience actually playing pen-and-paper games. It was really fun.

TIM CAIN

One thing Leonard said to me was, "I can't believe it's always so different." And I said, "It's different because you're all different." He played one session, then he came the next night and just watched. I said, "It's the same rooms, with the same GM, using the same rules, but because the players are so different, using different abilities and making different decisions, it will come out entirely differently."

He said, "Why don't we do that in computer RPGs?" I said, "I don't know. We should do that in ours." That was the genesis of, we want to make sure we track what the player does so that the game will be different for people who want to play differently, are acting differently, and are playing different types of characters.

Late-night GURPS sessions led organically to an idea: Why not build a roleplaying game from the ground up? It would be original, featuring a unique world and characters, and it would run on a known rules system licensed by Interplay.

CHRIS TAYLOR

The thing was that Interplay had been known for doing some really cool RPGs in the past. Brian Fargo wanted to do another RPG, so he sent out an email to the company and said, "We want to make an RPG. Here are three IPs we could license." One was Vampire: The Masquerade, which, you know, cool license.

The last one GURPS, and GURPS isn't so much a setting as it is a system, but it's a system that I liked to play, and a bunch of Interplay people liked to play, like Tim Cain. It was Tim Cain's go-to RPG system, and it was mine. We had ongoing GURPS games.

BRIAN FARGO

Of course, you only know about the games that were green-lit. You can imagine the games that were turned down: Hundreds of them. Sometimes people would come in and pitch me, and it just wouldn't grab me. I wouldn't like it, and sometimes I couldn't even put my finger on it.

TIM CAIN

Some of the other producers had complained that I was talking to their [teams] while they were trying to work.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

Tim sent out this email saying, "Whoever wants to design this game and talk about what this game could be, come after work," because he couldn't recruit people [away from other projects] to help him.

TIM CAIN

Since everybody could technically go home at six, I sent out an email saying, "I'm going to be in Conference Room 3 with a couple pepperonis and a cheese pizza at six. If you want to talk about developing a new game, I've got the engine partially written. I can show you what the features are. I can kind of show you how the scripting is going to work. Come by and we can talk about what genres you like."

I hadn't even picked that out. There was no art, no genre.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

Only five or six people showed up. Which, to me, was shocking. Even if you didn't want to design a game from scratch—and I couldn't believe people didn't want to be involved in that—there was free pizza! If you don't care about one, I'd think you'd care about the other.

TIM CAIN

I remember what was surprising at the time was how few people showed up. I expected there to be twenty or thirty people packed into that conference room because, hey, we can make whatever game we want! Instead there were maybe eight, ten.

Leonard Boyarsky, Chris Taylor, Scott Everts, Chris Jones, Jason Taylor, and Scott Campbell grabbed a slice and commenced brainstorming. That meeting, and that pizza, was the first of many.

CHRIS TAYLOR

I have to say, the thing that more than anything else made Fallout, Fallout, was those Coco—which is a restaurant in California—meetings. They have really tasty pancake dinners, so we would go there and eat sugar for dinner, and then throw out ideas. I'm sure Fallout came somewhere out of there.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

We all talked about it. It didn't matter what your job was; it didn't matter whether you were on a team or not; it didn't matter what you were doing on that team. We all sat together, and we talked about what we wanted our game to be at a very high level.

The conversations about the game were 100 percent after work. We knew we were going to make a GURPS game. Tim had convinced Brian Fargo to get the GURPS license, and GURPS is a generic system, so we had to figure out everything about it. We just knew what the system was going to be. Nothing about the narrative, nothing about the setting.

SCOTT EVERTS

I was working on Kingdom II: Shadoan at the time. Shadoan was our first 16-bit, color game. It was [based on a movie].

BRIAN FARGO

I was wearing my marketing hat, thinking, I'm filling a hole in the marketplace. For example, Blizzard is very brilliant at that. They're creative. When they did WarCraft, they said, "Everybody loves Dune. Let's do a [fantasy-themed] strategy game." That's as high-concept as you get. There was only one real-time strategy game of any notoriety [Dune II], I would say.

That was a very smart business decision: To look at a category. Sometimes I would look at things that way. Other times I'd look at them purely from a gamer's perspective, but one of the two had to intrigue me.

TIM CAIN

Chris Taylor was lead designer on Stonekeep, and that producer would not let him go. Chris Taylor was only allowed to talk to us after hours. We would meet. We would talk about all different genres. I said, "I don't want to make any decisions. I just want to talk about stuff." We talked about sci-fi games, horror games.

CHRIS TAYLOR

Tim was very inclusive. I had a huge GURPS collection, and I had a fairly good memory at the time. I don't now, but I could recall certain things from all the GURPS books that I owned. So, I would go [to meetings], and they would say, "We want to make two-headed cows. What are the rules for two-headed cows?" I'd remember there were rules in some book, so I'd say them. I was just kind of making myself helpful.

The team was in accord: They would make a roleplaying game. But what type? And what setting? The particulars were up for debate.

CHRIS TAYLOR

The very first iteration of the game was kind of a traditional fantasy game, just because we had some of those assets and were easy to [plug] in there. But they knew they didn't want to do a fantasy game.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

I just felt like everybody was doing that. If you're making an RPG, you're making an epic-fantasy game. I've always wanted to do stuff that no one else would have done. That's why when Tim, Jason, and I decided to make a fantasy RPG I said, "No, it should be a fantasy game, but after an industrial revolution. The technology and world should have kept moving after the fourteenth century.

I always want to see something different. I want to see something that other people haven't done in terms of setting. I wouldn't want our game to be confused with anybody else's. It's just a weird [stance] I've always had, and I didn't even realize it until I looked back on the projects I've done and the things I was interested in.

TIM CAIN

At one point it was post-apocalyptic, but aliens had caused [the end of the world], and humans were living on reservations. It was a whole bunch of crazy stuff.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

We started talking about a time-travel game. We had this whole story worked out and all these details about it. But it was a game you could just never make.

CHRIS TAYLOR

We would go to dinner at Coco's and throw out random game ideas about using the GURPS system to make multi-dimensional travel game where you started in a sci-fi world, went to a fantasy world, and there were cops and robbers, noir detective stories—all using the same system, but the settings would be different. Then someone sat down and budgeted how much art that would cost, and said, "Well, maybe we shouldn't do that."

TIM CAIN

We had a whole story written about time travel. It was going to be a film noir, detective adventure. We had it all written out and partially storyboarded. And then... I forget who—it might have been Michael Quarles on Stonekeep—he looked at it and said, "This is insanely complicated."

LEONARD BOYARSKY

There wouldn't be a lot of reuse of tiles. Fallout was a tile-based game. If you look at it, you can see it's built out of repeating tiles. It could have been made; anything could be made, within reason. But we would have had to make so many different tile sets. If you're going from time period to time period, there wouldn't be a lot of reuse between the areas you could build. It was simple economics.

And the story was pretty insane, from what I remember. It was this haphazard thing.

CHRIS TAYLOR

It was a multi-dimensional travel game that would have been really cool, because you had one character, and it took you through all these different worlds. Kind of like The Number of the Beast from [fantasy author Robert] Heinlein. Or Sliders, the TV show. It took you to all these variant worlds, and the rules would remain the same, but the settings would be different. Some of them would be serious, others would be more comical.

Tim had one little world where the bad guy broke the fourth wall: He knew he was in a computer game, so every time you defeated him, he would reload your save-game, and you had to steal the save-game disk before you could beat him permanently. Stuff like that that was really just super creative.

TIM CAIN

It had, like, thirty or forty main acts. To put it in perspective, Fallout had three. We threw it out.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

You can imagine: It was a bunch of guys in their mid to late twenties, sitting around a table, eating pizzas, talking about games they'd like to make. Somebody would say an idea, and somebody else would run with it. It would morph over time into something completely different. We threw out a bunch of ideas.

CHRIS TAYLOR

Another concept was going to be a sci-fi game set on a generation ship. We were actively trying to find ways of melding genres because of the strength of the GURPS system: Being able to incorporate all these different genres with one, unified rule system.

Tim even designed the game so that there was a game engine, and then there was the actual game. They were two separate things. All the content was separated from the underlying engine for how things attacked and all that stuff.

Tim Cain's notion to divide his engine into modules seemed prudent. Other trends that struck him as appealing at first ended up slowing down progress. The team rolled with punches, viewing technical and resource limitations as puzzles to solve.

TIM CAIN

3D was becoming popular, but 3D cards hadn't come out yet, so everything was software rendered. I made a 3D software renderer, and it was horrible. Really slow. I was talking with the guy making Star Trek: Starfleet Academy, and he had a 3D [software] renderer. I said, "Why is yours so fast and why is mine so slow?"

He goes, "Because I'm in space. I'm only rendering a ship. You're trying to render people wearing all this complicated gear, all this terrain, all these buildings." I said, "Well... shoot."

LEONARD BOYARSKY

Tim was really great in that a lot of people, when they're given control of a project, are just like, "I know everything about everything, and this is how everything is going to work. This is my creative vision; you do what I tell you to do." I think in one of the first conversations I had with Tim, he said, "I don't know anything about art, so you guys just make sure the art looks cool."

That was pretty much his artistic input. He loved what we were doing. If he didn't, he probably would have been more concerned with what was going on.

TIM CAIN

I switched to voxels, which are, like, two-and-a-half-D. They're pixels with height. I made all this really cool stuff, but the only thing that really worked was the islands.

ERIC DeMILT

Originally there was some disagreement over the wondrous abilities in a windowing system that one Interplay programmer had written. Tim was frustrated by that. This was back in the day when you had to write everything from scratch, so he wrote the framework for this thing that would later be used in a ton of Interplay products.

He was writing this framework, and was doing different things with it. He did a height field voxel renderer in it, just experimenting with different things.

TIM CAIN

Leonard was laughing because we were talking about this the other day. I said, "Remember I made that voxel-island game?" He said, "Yeah! Too bad we weren't making a game where you lived on islands."

LEONARD BOYARSKY

We were going to make it 3D in that we were going to use 3D programs to do the art. We talked about it being a first-person or third-person game. This might have been right around [the release of] Tomb Raider. Being somebody who was really involved in the art, not just in terms of [Fallout] but in terms of making stuff that I'd slaved over for years, I wanted to make sure it looked as good as possible.

TIM CAIN

I ended up playing with a 2D engine because Crusader: No Remorse was out, and I really liked the look. I got Jason [Anderson], who was newly hired, to make me a little knight walking around. I made the ground texture, with props on it, and the knight. That got me animation, sprites, a primitive UI with a mouse and some clicking.

I was so proud of that, that if you have an original Fallout 1 disc, there's a demo folder, and there's a demo.exe in there. It's that little game. It's not even really a game. It's you walking around a field full of boulders and flowers as a knight.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

We'd talked briefly about other 3D views, and I said, "Nope. We're not going to do them. You can't make the art look good enough." For me, the only way to do art that could have the kind of detail [in] characters was to say, "We're using 3D programs to make 2D sprites."

Fantasy and time travel were out. A post-apocalyptic setting featuring a unique blend of starkness and irreverence was more alluring, and shared much in common with an earlier Interplay-made RPG that had gone over well with players.

TIM CAIN

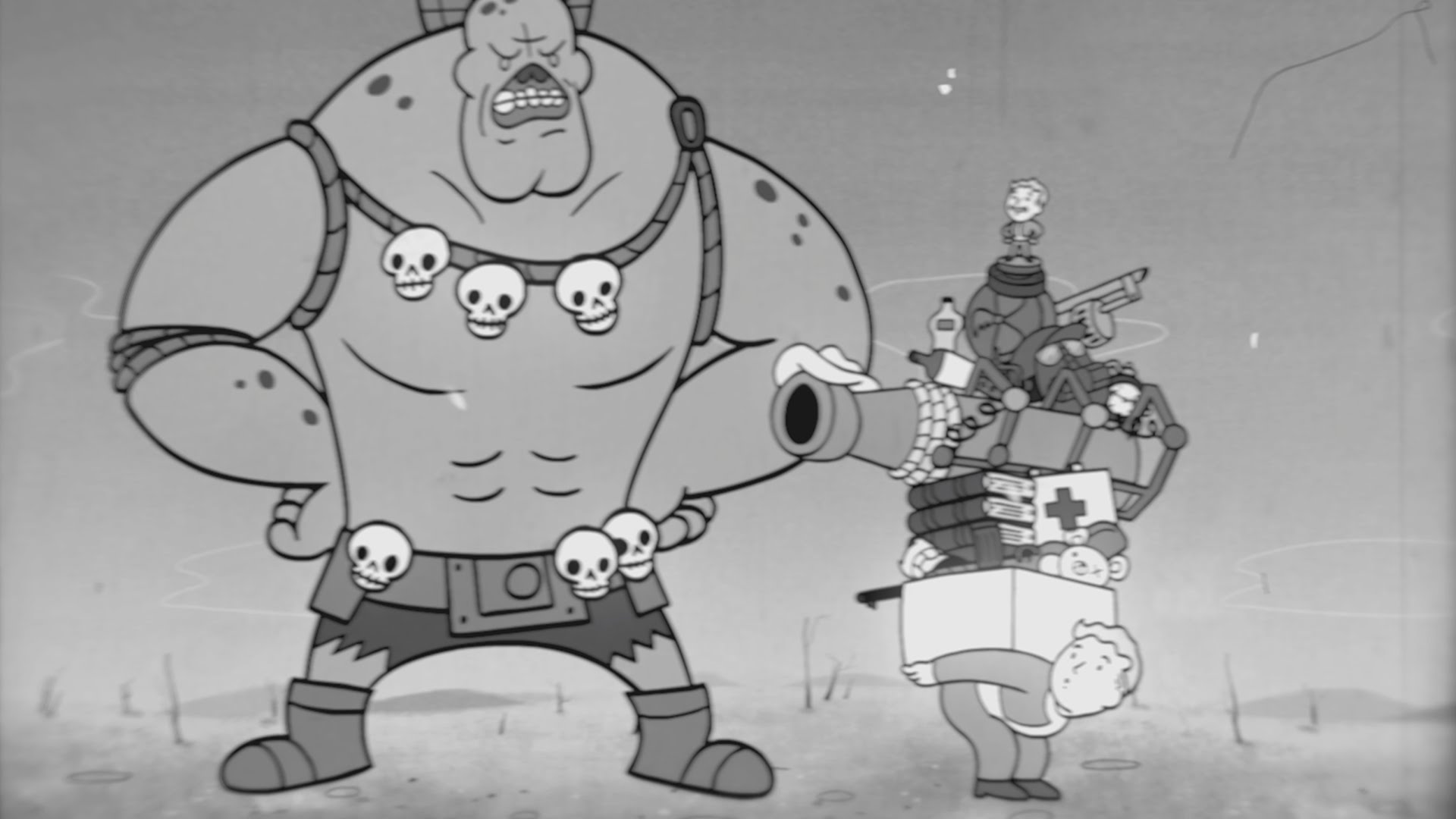

Once we decided to make it sprite-based, we had more meetings about genre. It was, "Okay, we're making a post-apoc [game] with a sprite engine." That's when Jason, Leonard, and a few other artists started churning a lot of sprites for us to use. It was very Mad Max: Road Warrior-esque at the beginning.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

It became what it was in terms of tone, in terms of comedy, in terms of the way we did humor yet how dark it was at the same time. That all came from these discussions. There was never a decision made, like, "This is how it should be." All of our personalities together—that's how we came up with it.

CHRIS TAYLOR

Because we had the GURPS system, the setting was really up to us. When I came on, it was already post-apocalyptic. It wasn't called Fallout yet, but it was still using GURPS.

In fact, the game was originally going to be called Armageddon, but there was another producer at Interplay who wanted to make an Armageddon-themed game, so he said we couldn't use that title. Then that title eventually got cancelled or never made, so we had to come up with Fallout to replace a title for a game that never got made.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

The post-apocalyptic [direction] was something Jason and I were pushing really hard. We were big Road Warrior fans, and we didn't want to make a fantasy game. At one point, the apocalypse was caused by aliens invading.

TIM CAIN

Chris Taylor loved Wasteland, and Leonard loved Road Warrior. We said, "Why don't we just try post-apoc?" It was easy to have adventures if there wasn't a lot of that type of environment around. That's when Brian said, "I may be able to get the Wasteland license. We could make this Wasteland 2." We were like, "Okay! We're post-apoc!"

CHRIS TAYLOR

Brian Fargo had come to us and said he wanted to do, basically, the next Wasteland. There were things that he'd had like, "Exploding like a blood sausage," text in ways that he wanted to see it. That was probably the genesis moment for the over-the-top violence, deaths, and stuff like that.

But he also had other things from Wasteland that he wanted to see in there. He talked about this one moment where you run into this boy, and his dog is missing, and you kill this rabid dog that it turns out was the boy's dog. It wasn't a black-and-white quest. There was a lot of gray. No matter what, you couldn't make the exact right decision. That influenced the design.

TIM CAIN

Some of us had played Wasteland, and some of us hadn't. After a while, we all sat down and played it after we decided it would be post-apoc. After we decided that, that was the first time we got Fargo's direct attention. He asked to get the Wasteland license from EA.

They spent a year trying to do that. EA just strung them along, and there was no intention of ever giving them the license.

Interplay’s failure to wrangle the Wasteland license from Electronic Arts’ grip was a blessing in disguise. Free of the rules and lore of an existing franchise, the Fallout team was free to brainstorm their own apocalyptic setting and trappings. Leonard Boyarsky hit on a unique medley at a time when his brain was moving a million miles a minute, while his car wasn't moving at all.

TIM CAIN

We were very much an '80s or '90s-style post-apoc, whatever you want to view Mad Max as. Leonard had the idea.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

I had this really long drive [home]. I was stuck in traffic, and my mind was wandering. I thought, You know what would be really cool? If this was a 1950s future. I don't know why I thought that would be cool. I don't know why I thought that would work with a post-apocalyptic setting.

TIM CAIN

He said, "What if we do post-apocalyptic worlds the way that movies in the 1950s thought it would happen?" An atom bomb went off and that made monsters, mutants, and horribly irradiated people. They thought, Well, science will get us through this. Science created this nightmare and science will get us through it.

We were like, "That's great," because we could have a lot of fun with that optimism.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

I went into work the next day and told a bunch of people. They all looked at me like I was insane. I remember specifically the first person I told was Rob Nesler, and he looked at me like I was insane. But he said, "Well, you seem really passionate about it. You should just do it, see how it goes."

That was fantastic. I don't know why they had faith that Jason and I could pull this off, with the help of the artists working with us.

TIM CAIN

That idea simultaneously made Fallout go in the direction it did: A '50s-style future, but also the kind of humor we liked, too, which was very dark and silly.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

I feel like a lot of elements were already there, and [this direction] helped them coalesce into something bigger. We had some of the Vault-Tec stuff. We had the idea of the Pip-Boy. I believe even the name "Vault Boy" was already there.

So it was kind of weird that we were already making this 1950s-B-movie version of the apocalypse. I felt like the next step was to go all the way and make it a 1950s-B-movie version of the apocalypse.

TIM CAIN

Leonard's dark and I'm silly, so we made Fallout dark and silly, which was a very interesting tone. It made Fallout feel unique among other RPGs that Interplay was making.

LEONARD BOYARSKY

It's funny, because I look back on it, and, yeah, we knew we were going to be making this game, but it was really the spirit of, we weren't in a garage, but it was like we were. Anything goes. Whatever we want to do. No one was there to tell us what we should or shouldn't do, or what we could do.

It was this purely creative [time] with a bunch of people having fun, talking about what a great game would be.

Building Blocks

With a theme in mind and the formal partnership of GURPS license-holder Steve Jackson Games in place, Fallout's small team set about defining technical staples.

TIM CAIN

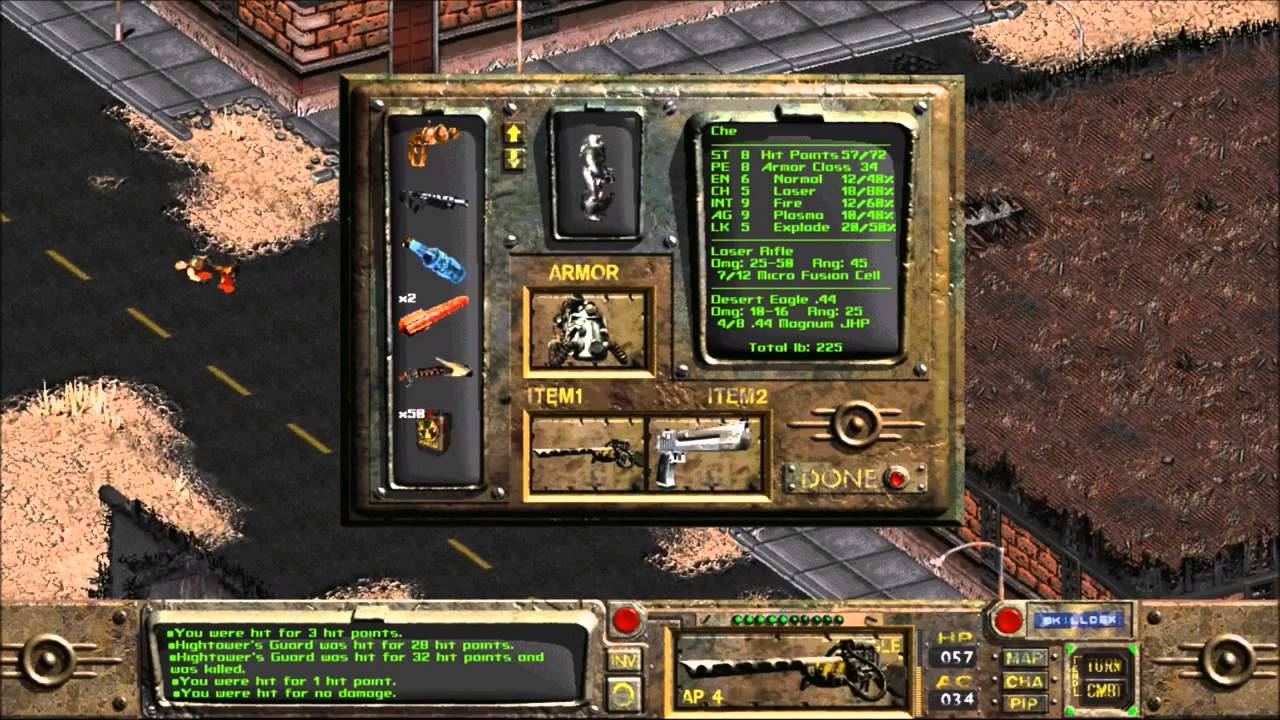

We really loved turn-based, tactical fighting. That was another way for us to distinguish ourselves from the real-time-with-pause RPGs that were coming out, because we were pure turn-based.

CHRIS TAYLOR

Stonekeep finally finished and shipped, and there was brief talk of doing a Stonekeep 2, but we were kind of sitting around. That's when Scott Campbell left the team, and they needed a new lead designer.

Because I was familiar with GURPS, and I was friends with a lot of people on the team, it just seemed like a really good fit, and it was. I slotted right in.

TIM CAIN

It was really complicated, too, because originally we tried to print out tiles using the same camera perspective we were going to have in the game. That introduced perspective issues, so the way we ended up doing it was we pulled the camera back to infinity and then zoomed in. That made all the lines fairly parallel.

That's why [Fallout] isn't really isometric; it's oblique, that 60/90 angle we picked, which is trimetric, not isometric.

CHRIS TAYLOR

A lot of the areas were already designed. The core storyline of being in the Vaults, the Vault Dweller—that was all there, but it was all high-level stuff. One of the first things I did was just kind of trim some of the fat, get it down to a little more manageable size, focus the story a little bit.

Then we started doing more in-depth level design with maps, map keys, and, "Here's these kinds of monsters and they have these kinds of stats," and "Here are these NPCs, who will say these kinds of things to you," and, "Oh, here are all the quests you can do."

TIM CAIN

Also, the fact that there's no perspective loss. When the buildings slope away, they don't get any smaller up top than they are at the bottom, which you have to have in an isometric game.

But it's very hard to make a 3D engine do that because a 3D engine wants to make it three-dimensional and slowly dwindle as it goes off in one direction. That was really hard to account for. Back then we had to fake it by pulling the camera out to infinity then pulling it back in, zooming back in from infinity.

CHRIS TAYLOR

My first couple of weeks were spent editing. Like, "Well, this area makes a lot of sense, because it's got something that's duplicated by this area over here," or "These characters don't really work together." I just spent a lot of my time going through documents that were already there with a red pen, highlighting things, crossing some things out, making some notes.

There was a team of designers I worked with, and we assigned areas to each one of them and worked from there. But there was so much work already done when I got there that it was more a question of picking and choosing the right elements to incorporate into the game than having to create from scratch.

Players begin in the dim recesses of Vault 13, one of few underground dwellings where survivors took shelter during the nuclear holocaust. Life in Vault 13 is claustrophobic and predictable—until the chip responsible for filtering clean water is broken. Assuming the role of a Vault Dweller, players are tasked with finding a replacement water chip within 150 days. Any longer, and Vault 13's inhabitants will die of thirst. Players leave the Vault and enter a cave infested with rats standing between them and the surface.

CHRIS TAYLOR

Designers were assigned: "Here's your area, start fleshing it out." I came up with a template for level-design documents, and it wasn't as rigorous as what you have nowadays.

SCOTT EVERTS

I'm pretty sure I had finished up on Shadoan. I wasn't assigned on a project. I was doing Fallout on the side. Interplay was very loose. You could bounce around things, and no one cared too much.

If I remember correctly, they were planning to have the designers lay out the levels. I was talking with Tim [Cain], and I'd played GURPS with him. We'd played various games together. We had a big Atari Lynx group that used to play every week. I offered to take a crack at doing the demo level, and they liked it, and then asked me to do the rest of the levels.

CHRIS TAYLOR

I would have killed for a wiki back then, some kind of online, collaborative tool so we could all work on the same document. We had to pass around floppy disks with Word documents on them. Keeping versions [organized] was scary.

TIM CAIN

Before we had [professional] VO, Scott Everts did a lot of our VO. When you shot someone, you'd hear Scott go, "Owie." BANG! BANG! "Owie, owie." When I did the flamethrower, it was going to start that "Owie" when everybody got hit by a flame. It would play the sounds a millisecond apart.

So there were around seven instances of that sound effect starting closely together, and it made this weird, stretched-out noise, like, "OOOOOOOWWWWWIIIIIIIEEEEEEE." It was very funny because Scott came running in to find out what the noise was, and I said, "It's actually you, stretched out in WAV form."

CHRIS TAYLOR

I'm pretty sure I started with Vault 13, because that was the [early] part of the game, and I wanted to get the early gameplay experience designed first, knowing that we'd probably go back and revisit it. It's the player's first impression of the game, so you want to make it tuned and as good as possible. But we needed to have some starting point, and I think I just picked Vault 13.

SCOTT EVERTS

When I was doing Fallout 1, a designer would draw stuff out in a drafting program. He would have a grid and say, "Here's a building. Doors are here, so you can come in this side. The interior walls are like this." They may write a note saying, "This is the boss's room. Its lieutenant is here. There's an encounter over there."

CHRIS TAYLOR

The way my process worked was I used a graphic illustration program to lay out the maps and design levels in 2D, and then I went in and keyed the maps. In [Microsoft] Word, I'd open up a document and write, "In Area 1, here's the description, here's these characters, these items." It's listing contents so the artists know what they need to create, the level designers know what they need to put down, the programmers know what scripts they need to create, and all that good stuff.

I started with Vault 13 and laid everything out, working on the rat cave at the very beginning, working my way out from there.

TIM CAIN

When you shot projectiles, it just referenced a piece of art, like, "Here's the projectile to use." One of the designers had hastily thrown in the rocket launcher, but instead of putting in the art ID for a missile, he put in the ID for a guard, so the rocket launcher shot guards. Instead of looking like they shot out of the rocket launcher, they just appeared running in midair, running toward the target.

SCOTT EVERTS

I would sit down, and what I'd do first is just put down some walls. Nothing else. Then I would show the designer. He'd say, "That's good. Why don't we move this building closer to over here," or "Let's put cover over here so you can sneak past this point."

Once we got all that done, and we had buildings where we wanted them and rooms set up the way we wanted them, I'll go in and decorate. I'll put in ground details, interior details, shelving, junk, all that sort of thing. We'd do it in sections. You don't want to just finish all of it before reviewing it with the designer. It’s a lot easier to nail down the important locations before spending time on decorating. You don’t want to have to rebuild everything.

CHRIS TAYLOR

The process was pretty much the same for everyone: Start in an area, do an overview, detail the maps, expand on the maps and the level design, and finally, work on the dialogue. I enjoy doing that, and I think my dialogue was pretty well received, but it's painful for me to write dialogue because I hate the way it sounds when I say it. I'm constantly sitting there talking out loud, rewriting it. I probably annoyed my officemates way too much.

TIM CAIN

The designer then changed it to be the Dogmeat model, which we all thought was funny: We had a launcher that shot dogs. It turned out that the Tick, the animated show, there was this female character—I don't know if she was a hero or villain—who had a poodle gun. A gun that shot poodles at people. We were like, "We just put that in our game."

SCOTT EVERTS

That first level is all about teaching you how systems work. That's basically a tutorial: this is how combat works; this is how you attack. The enemies aren't too dangerous, so you can't get too screwed up if you do a bad job of [combat]. That's really the whole point of that level. Rats made sense there, and if we did [the game] now they might be something different.

An awful lot of it was by the seat of your pants. It was, "We need to come up with a new level, and we need some enemies." I wasn't very involved in choosing what the enemies would be, because, really, all that level was designed for was to get you out into the world. You get that nice, opening video where the door opens, and you emerge in a cave, and then you see rats scurrying around.

I think you can outrun them, too. You can just run out of the cave. We didn't tend to overthink it back then.

CHRIS TAYLOR

We had another guy, [designer] Mark O'Green. He ended up writing a lot of the spoken dialogue for the characters, and it was fantastic. His process for creating dialogue was so much more efficient than mine. It was really cool to watch, and working with him helped me do dialogue for games I've done since then.

Vaults 13 and 15 are two of Fallout's most iconic locations. Junktown, a small outpost in the game's incarnation of southern California cobbled together out of wrecked cars, is another. The town hosts a number of attractions, from a casino (allegedly) riddled with cheating to stores where players can stock up on supplies. It’s also the starting point for several quests. Scott Everts built it tile by tile. In parallel, more of the gameplay mechanics that would allow players to explore the town and interact with its inhabitants at their own pace came online.

SCOTT EVERTS

I said, "Let me play with the editor." I threw together the original Junktown. Tim said, "Wow, this is pretty cool. Do you want to do all of [the areas]?" I put some overtime in, I did some stuff on the side, basically just to get this [demo] together.

That's the way the industry worked back then: "We need bodies. Who can do what?" It took a lot of load off the designers, because now all they have to do is tell me what they want.

TIM CAIN

The first thing I learned was that no player ever does what you think they're going to do.

CHRIS TAYLOR

I like that you can turn on Killian or go after Gizmo, the play between those two. I think that's really central to the core of what Fallout is. Fallout is giving the world to the player and saying, "Yeah, if you want to do this, do it. There's a reaction to it. Or if you want to do that other thing, do that. I don't care what you do, but you will care, because there will be consequences for your actions."

I think that option to play the sheriff versus the gangster in that one city is probably my favorite quest line, just because it is, in my mind, so stereotypically Fallout.

SCOTT EVERTS

I remember going out to a restaurant, and we were working on... I think it was the first raiders' camp. We were drawing on napkins: building here, building there, this person's over here. They would say, "Do what you want. Make it look cool." That's basically how we did all the levels. I'd sit down with a designer and we'd figure out where all the important things were.

TIM CAIN

When I was GM'ing, I tried to make a storyline, but I'd take a lot of notes about, okay, if they decide to explore this village, here's some stuff that's interesting; if they go into the forest, here are things that are interesting. Basically, if they don't go to the dragon cave, here are other things around that are interesting to do.

Judges Guild, an old, now-defunct company, made supplements like that that I thought were far superior to what TSR was putting out at the time. That influenced me a lot.

CHRIS TAYLOR

I was often rooming with Scottie, so I got to see the levels as they were created. It was really neat. If you've seen a Dungeons & Dragons map, those were kind of what I'd create. I'd use squares and draw them out, and then Scottie would take it and make it look cool. He'd be building.

SCOTT EVERTS

Originally it was just walls. One of the problems with our editor was you had to really, really get to know it. There was no category system. There was just a row of art in no particular order, like, here are all the tile pieces, here are prop pieces.

What they did was they drew these ground details and then just dropped them into a tile-cutting program to cut them up. Designers would just lay down one tile [theme], put some buildings in there, and some tables and chairs, and that was it. I had to learn how pieces fit together. It was like a big jigsaw puzzle.

ERIC DeMILT

I think the only meaningful impact I had on the game in terms of production—and this is now kind of a joke internally—but there was this "What Would Eric Do?" play path that Tim would test for, because I used to murder everything in the game. We still have “What Would Eric Do?” design questions in the games we work on today.

TIM CAIN

When we were making Fallout, one of the things I used to say to the designers was, "We have a main story arc, and I always want to make sure I can talk my way through it, or sneak my way through it, or fight my way through it. But then I want you to remember what happened so that later on, the game can be a little different."

Or, if it's the end of the game, we can show you a very different [ending] for somebody who killed everybody, versus somebody who got both sides to work together and everybody was living in possibly an uneasy truce, but they're still alive and Junktown is functioning.

I wanted the player to know: "We saw you do that, and the game's going to react to it."

TIM DONLEY

After Shattered Steel, the next game I worked on full-time was Rock 'n' Roll Racing 2. During that, I was helping with Fallout. Everybody had to [work on multiple projects] at some point because there were a few products they were trying to pull together. You'd get pulled off one project [for another]. Like, okay, I'm working on Rock 'n' Roll, but I'm helping out with Fallout.

I didn't know a lot about Fallout and they said, "Go talk to Tramel [Ray Isaac] and Brian." Tramel was one of the artists who was on it, and he would play all the time. Now, I had no idea what the game was about. I had nothing except post-apocalyptic stuff. He's sitting there with Jason [Anderson], who was also one of the designers/artists on it. Jason's standing behind him watching, and Tramel is walking through a town. He had a hammer, and he was hitting characters with this hammer, and every time he'd hit him they'd fall to the ground dead, and they'd slide into walls or hit something.

CHRIS TAYLOR

We'd put the level into the game, play it for a little bit. It'd be rough in the beginning. He'd fine-tune it after we were happy with the placement of the walls, the doors, stuff like that.

ERIC DeMILT

There's an NPC named Gizmo. He's the only [character] built into a piece of furniture: He's a big, fat crime lord sitting in a chair. He didn't have any death animations, and they put this super-difficult-to-kill guard in his room. You were supposed to chat him up and figure out what quests you needed to do so you could progress his quest line. I made a character and min-maxed the crap out of sniping and critical hits, so I managed to kill his guard and then kill him.