The Second Attempt

You would think that after the operation had been blown, with so many arrested and imprisoned, that the tunnellers would give up. They didn’t. They knew the Stasi had no details about their original tunnel and so they decided to try again.

This time, they would keep the details tighter and the group of diggers smaller. It was now September 1962, and the original tunnel had dried out enough to allow work to re-start. But before long, it sprang another leak.

This time, they were too far into the East for the West German water authorities to fix it. The diggers would either have to abandon the tunnel or break through into a random basement.

Using their maps, the tunnellers worked out they were now under Schönholzer Strasse, a street in the East that was so close to the wall it was patrolled by border guards.

Tunnelling up there would be a huge risk - it would be noisy, and what's more, any escapees would have to walk past the border guards to enter the cellar.

It was hard to imagine how it could work, but these diggers had proved they were brave and they were determined to give it another go.

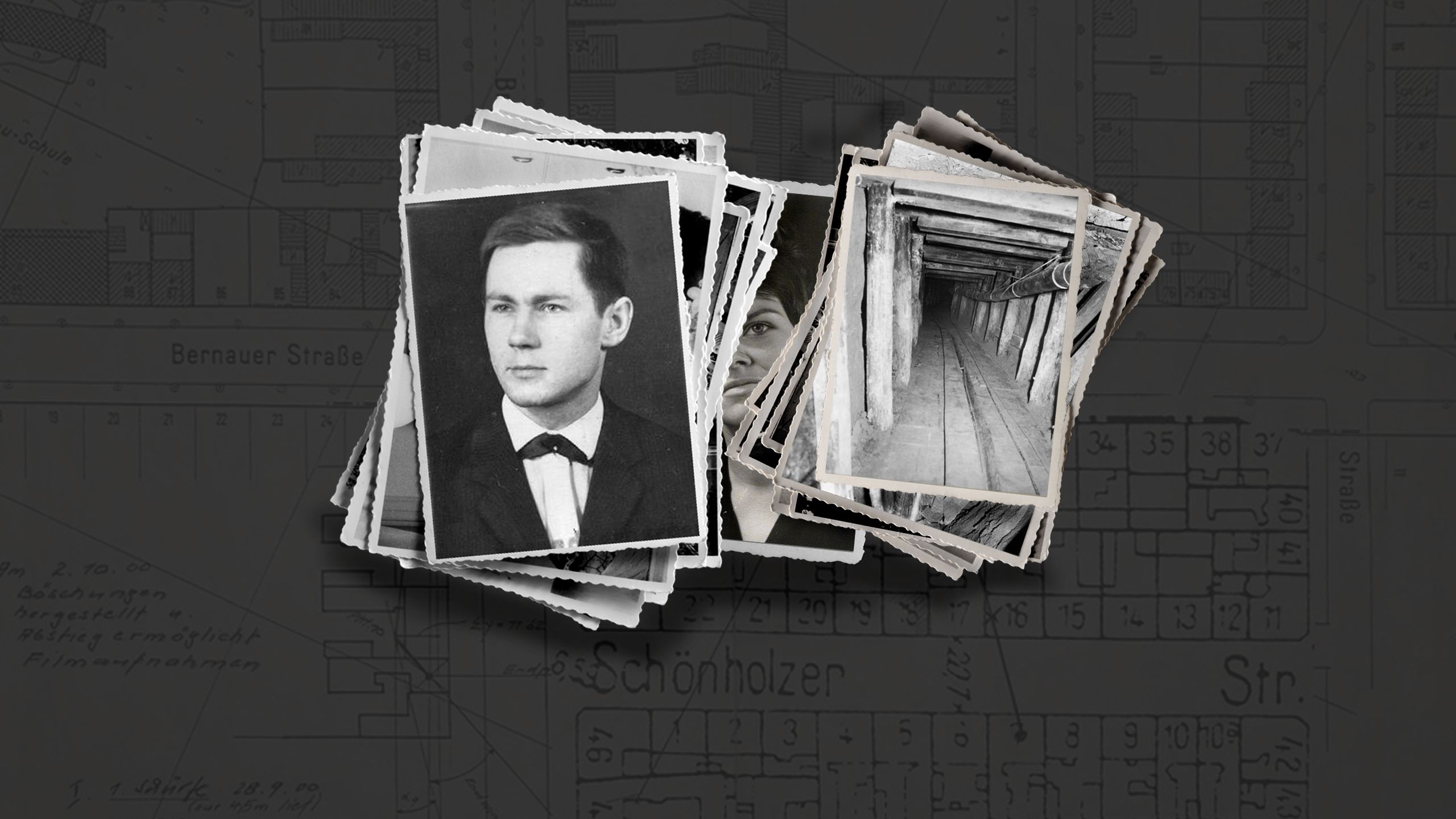

Tunnel 29, after the leak had dried out.

Tunnel 29, after the leak had dried out.

The date was set for 14 September. Some students volunteered to go into the East and tell the escapees the new plan. But like last time, they would need a messenger to cross the border on the escape day itself and give signals, so that the East Berliners would know when to go to the tunnel.

Unsurprisingly, after what happened to Wolfdieter, no-one was keen to step forward. But then one of the tunnellers, Mimmo, had an idea - what about his 21-year-old girlfriend, Ellen Schau? Like Wolfdieter, she had a West German passport so she could go in and out of the East, and as a woman, perhaps she would arouse less suspicion? Ellen agreed to do it.

The escapees had been told to go to three different pubs and wait. Once the tunnellers had broken through into the cellar, Ellen was to go to each of these pubs and give a secret signal.

Ellen was filmed as she boarded a train into the East. Wearing a dress, headscarf and sunglasses, she looks like a 60s movie star. You see her check her watch. It’s midday. She turns towards the station and runs up the stairs.

A road block at the border to East-Berlin

A road block at the border to East-Berlin

Meanwhile, Joachim and Hasso began hacking into the cellar of an apartment on Schönholzer Strasse. Joachim eventually climbed up into the cellar and unlocked the door to the apartment lobby using a set of skeleton keys.

He needed the number of the apartment they'd dug into. First, he went into the hall. No number there. And he realised the only way to find out was to go outside into the street - the street that was patrolled by border guards.

He opened the front door to the building and saw a group of guards sitting in a hut. They were distracted, so he slipped out into the street. “There was a big number seven just above the door,” he says.

They used their trusty WW2 telephone to get a message to the rest of the team, who were in a West Berlin flat overlooking the wall. A white sheet was draped from the window - Ellen’s signal that the escape was on. From the East, Ellen saw the sheet and went to the first pub to start giving the signals.

“It was really loud,” Ellen remembers. “And when I walked in, the men all turned round and looked at me. The signal was for me to buy a box of matches. So I walked up to the bar, and that’s when I noticed these people staring at me.”

It was a family, sitting at a table. The mother was wearing a dress and high heels, holding her toddler on her lap. Ellen ordered the matches and left. In the next pub she ordered some water - that was the next signal.

When she arrived at the final pub, things didn't go quite to plan. The signal there was for her to order a coffee, but the waiter said they had run out. “It was a terrible moment,” she says. “How could I give the signal if the pub didn’t have any coffee?”

Instead, she started complaining loudly about the coffee, and ordered a cognac. She drank it, turned around, saw two families waiting and hoped they understood the signal. She left the pub. Her job was done.

As she made her way back to West Berlin, small groups of people started walking towards Shonholzer Strasse. They were doing their best not to stand out, just a few at a time.

Joachim and Hasso were waiting in the cellar, guns in their hands. Just after 18:00, they heard footsteps. “We stood there, hardly breathing, gripping our guns tightly,” says Joachim.

The door opened. The mother from the first pub, Eveline Schmidt, stood there, with her husband and two-year-old daughter. They were helped down into the tunnel. “It was dark,” says Eveline. “There was just one lamp by the entrance. One of the tunnellers took my baby and then I started crawling.”

Eveline Rudolph with her daughter Annett, whose shoes Joachim finds in the tunnel

Eveline Rudolph with her daughter Annett, whose shoes Joachim finds in the tunnel

At the other end, in the West, the two-man NBC film crew were standing at the top of the tunnel shaft. In the footage of this moment, for a long time nothing happens, and then suddenly a white handbag appears. Then there’s a hand, and then, finally, Eveline.

She’s covered in mud, her tights are torn and her feet are bare. She’s lost her shoes somewhere in the tunnel. It’s taken her 12 minutes to crawl through it. She looks up towards the camera, blinking into the light. And then she starts climbing the ladder up into the cellar. Just as she reaches the top, she collapses.

One of the NBC cameramen catches her and helps her to a bench. She sits there, shaking, and then one of the tunnellers brings her baby to her. She bundles her into her arms, nuzzling the nape of her neck.

Over the next hour, more people came. There was Hasso’s sister, Anita, and others - eight-year-olds, 18-year-olds, 80-year-olds. By 23:00, almost everyone on their list had made it through.

The tunnel was filling with water, but one digger was still waiting. His name was Claus, and he was hoping his wife, Inge, might come.

Inge had been sent to a communist prison camp after she was caught trying to escape with him. She’d been pregnant at the time and he hadn’t seen her since.

In the NBC footage, the camera is focused on the tunnel. Suddenly, a woman emerges. Claus pulls her towards him, but she carries on going - she doesn’t recognise her husband in the dark. He looks up after her, then hears another noise coming from the tunnel.

It’s a baby, dressed in white, carried by one of the tunnellers. He’s tiny - only five months old. Claus bends down and gently takes the child, delivering it from the tunnel. It’s a boy, his son, born in a communist prison.

Back at the other end, in the East, Joachim was still in the cellar. Twenty-nine people have made it through. With the water up to his knees, he knew it was time to go. “So many things went through my head,” he says.

“All the things we’d gone through digging it. The leaks, the electric shocks, all the mud, so much mud, the blisters on our hands. Seeing all those refugees come through, I felt the most incredible happiness.”

Wolfdieter and Renate on their wedding day in 1966

Wolfdieter and Renate on their wedding day in 1966

A few months later, NBC broadcast the film, despite an attempt by President Kennedy’s White House to block it, fearing a diplomatic incident with the Soviet Union.

It was described as without parallel in the history of television. The tunnellers heard that President Kennedy himself watched it and that he had been moved to tears.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2C3fBYY

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.