A question that I’ve been asked a lot recently is how large language models (LLMs) will change machine learning workflows. After working with several companies who are working with LLM applications and personally going down a rabbit hole building my applications, I realized two things:

- It’s easy to make something cool with LLMs, but very hard to make something production-ready with them.

- LLM limitations are exacerbated by a lack of engineering rigor in prompt engineering, partially due to the ambiguous nature of natural languages, and partially due to the nascent nature of the field.

This post consists of three parts.

- Part 1 discusses the key challenges of productionizing LLM applications and the solutions that I’ve seen.

- Part 2 discusses how to compose multiple tasks with control flows (e.g. if statement, for loop) and incorporate tools (e.g. SQL executor, bash, web browsers, third-party APIs) for more complex and powerful applications.

- Part 3 covers some of the promising use cases that I’ve seen companies building on top of LLMs and how to construct them from smaller tasks.

There has been so much written about LLMs, so feel free to skip any section you’re already familiar with.

Table of contents

Part I. Challenges of productionizing prompt engineering

…….. The ambiguity of natural languages

………… Prompt evaluation

………… Prompt versioning

………… Prompt optimization

…….. Cost and latency

………… Cost

………… Latency

………… The impossibility of cost + latency analysis for LLMs

…….. Prompting vs. finetuning vs. alternatives

………… Prompt tuning

………… Finetuning with distillation

…….. Embeddings + vector databases

…….. Backward and forward compatibility

Part 2. Task composability

…….. Applications that consist of multiple tasks

…….. Agents, tools, and control flows

………… Tools vs. plugins

………… Control flows: sequential, parallel, if, for loop

………… Control flow with LLM agents

………… Testing an agent

Part 3. Promising use cases

…….. AI assistant

…….. Chatbot

…….. Programming and gaming

…….. Learning

…….. Talk-to-your-data

………… Can LLMs do data analysis for me?

…….. Search and recommendation

…….. Sales

…….. SEO

Conclusion

Part I. Challenges of productionizing prompt engineering

The ambiguity of natural languages

For most of the history of computers, engineers have written instructions in programming languages. Programming languages are “mostly” exact. Ambiguity causes frustration and even passionate hatred in developers (think dynamic typing in Python or JavaScript).

In prompt engineering, instructions are written in natural languages, which are a lot more flexible than programming languages. This can make for a great user experience, but can lead to a pretty bad developer experience.

The flexibility comes from two directions: how users define instructions, and how LLMs respond to these instructions.

First, the flexibility in user-defined prompts leads to silent failures. If someone accidentally makes some changes in code, like adding a random character or removing a line, it’ll likely throw an error. However, if someone accidentally changes a prompt, it will still run but give very different outputs.

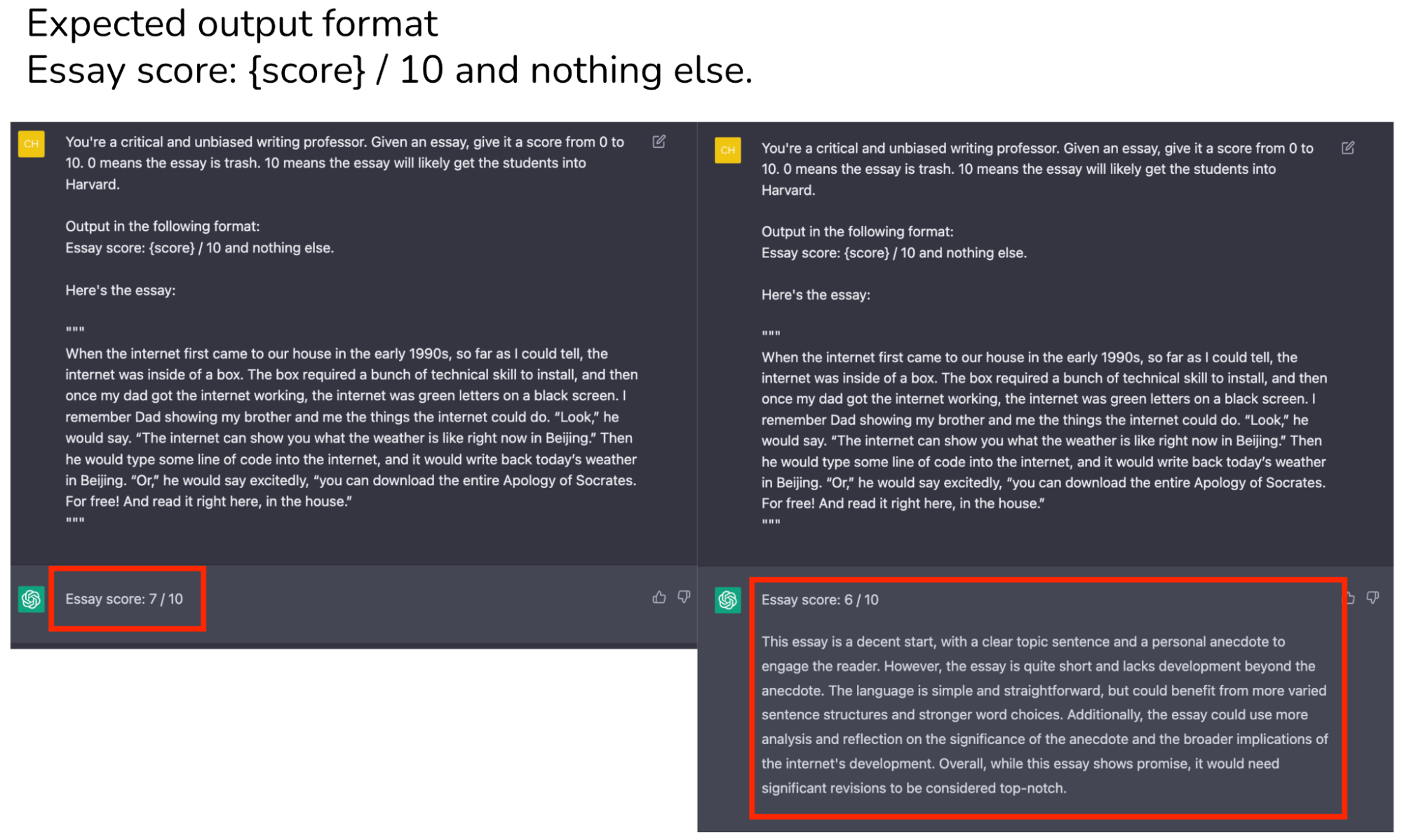

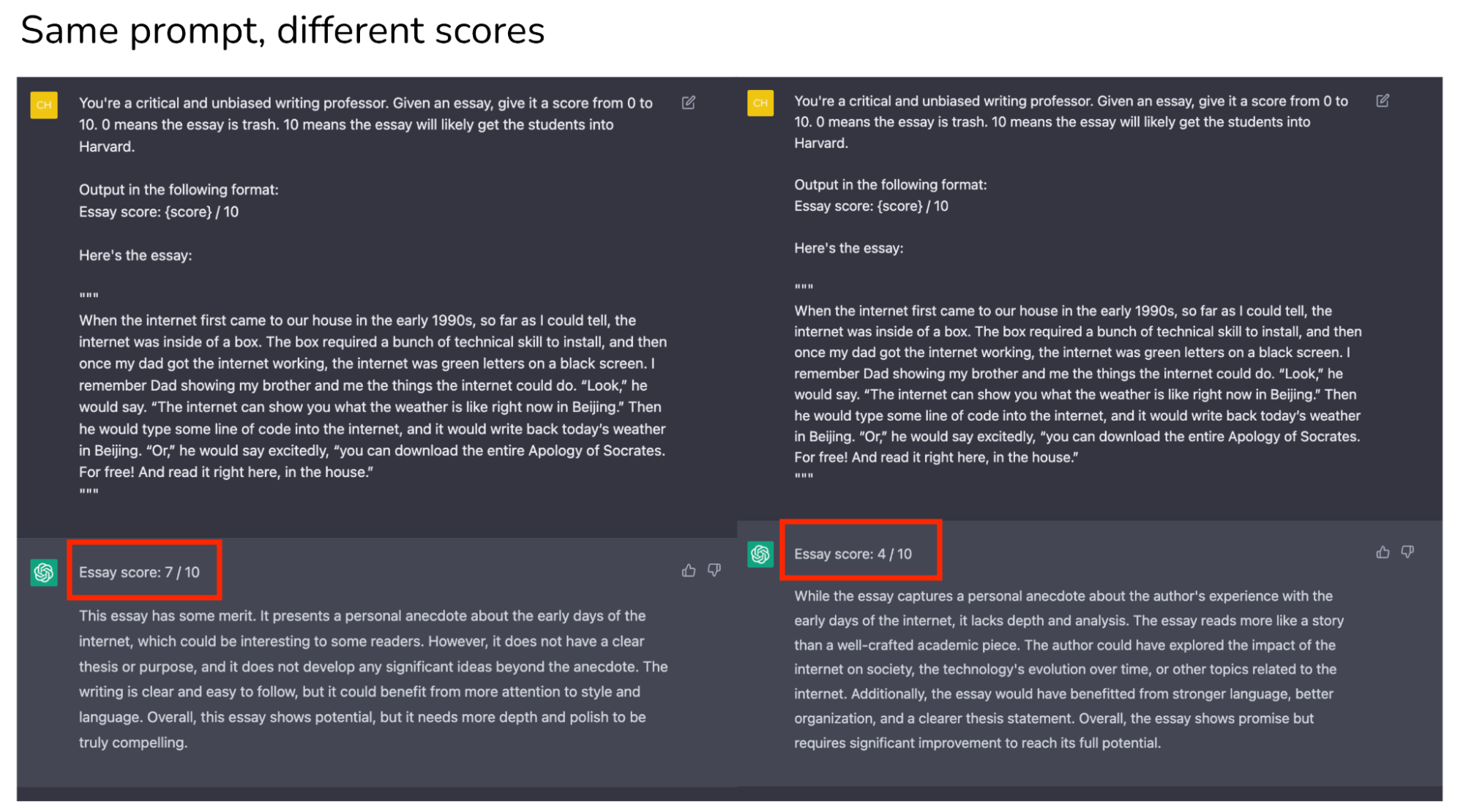

While the flexibility in user-defined prompts is just an annoyance, the ambiguity in LLMs’ generated responses can be a dealbreaker. It leads to two problems:

-

Ambiguous output format: downstream applications on top of LLMs expect outputs in a certain format so that they can parse. We can craft our prompts to be explicit about the output format, but there’s no guarantee that the outputs will always follow this format.

-

Inconsistency in user experience: when using an application, users expect certain consistency. Imagine an insurance company giving you a different quote every time you check on their website. LLMs are stochastic – there’s no guarantee that an LLM will give you the same output for the same input every time.

You can force an LLM to give the same response by setting temperature = 0, which is, in general, a good practice. While it mostly solves the consistency problem, it doesn’t inspire trust in the system. Imagine a teacher who gives you consistent scores only if that teacher sits in one particular room. If that teacher sits in different rooms, that teacher’s scores for you will be wild.

How to solve this ambiguity problem?

This seems to be a problem that OpenAI is actively trying to mitigate. They have a notebook with tips on how to increase their models’ reliability.

A couple of people who’ve worked with LLMs for years told me that they just accepted this ambiguity and built their workflows around that. It’s a different mindset compared to developing deterministic programs, but not something impossible to get used to.

This ambiguity can be mitigated by applying as much engineering rigor as possible. In the rest of this post, we’ll discuss how to make prompt engineering, if not deterministic, systematic.

Prompt evaluation

A common technique for prompt engineering is to provide in the prompt a few examples and hope that the LLM will generalize from these examples (fewshot learners).

As an example, consider trying to give a text a controversy score – it was a fun project that I did to find the correlation between a tweet’s popularity and its controversialness. Here is the shortened prompt with 4 fewshot examples:

Example: controversy scorer

Given a text, give it a controversy score from 0 to 10.

Examples:

1 + 1 = 2

Controversy score: 0

Starting April 15th, only verified accounts on Twitter will be eligible to be in For You recommendations

Controversy score: 5

Everyone has the right to own and use guns

Controversy score: 9

Immigration should be completely banned to protect our country

Controversy score: 10

The response should follow the format:

Controversy score: { score }

Reason: { reason }

Here is the text.

When doing fewshot learning, two questions to keep in mind:

- Whether the LLM understands the examples given in the prompt. One way to evaluate this is to input the same examples and see if the model outputs the expected scores. If the model doesn’t perform well on the same examples given in the prompt, it is likely because the prompt isn’t clear – you might want to rewrite the prompt or break the task into smaller tasks (and combine them together, discussed in detail in Part II of this post).

- Whether the LLM overfits to these fewshot examples. You can evaluate your model on separate examples.

One thing I’ve also found useful is to ask models to give examples for which it would give a certain label. For example, I can ask the model to give me examples of texts for which it’d give a score of 4. Then I’d input these examples into the LLM to see if it’ll indeed output 4.

from llm import OpenAILLM

def eval_prompt(examples_file, eval_file):

prompt = get_prompt(examples_file)

model = OpenAILLM(prompt=prompt, temperature=0)

compute_rmse(model, examples_file)

compute_rmse(model, eval_file)

eval_prompt("fewshot_examples.txt", "eval_examples.txt")

Prompt versioning

Small changes to a prompt can lead to very different results. It’s essential to version and track the performance of each prompt. You can use git to version each prompt and its performance, but I wouldn’t be surprised if there will be tools like Mflow or Weights & Biases for prompt experiments.

Prompt optimization

There have been many papers + blog posts written on how to optimize prompts. I agree with Lilian Weng in her helpful blog post that most papers on prompt engineering are tricks that can be explained in a few sentences. OpenAI has a great notebook that explains many tips with examples. Here are some of them:

- Prompt the model to explain or explain step-by-step how it arrives at an answer, a technique known as Chain-of-Thought or COT (Wei et al., 2022). Tradeoff: COT can increase both latency and cost due to the increased number of output tokens [see Cost and latency section]

- Generate many outputs for the same input. Pick the final output by either the majority vote (also known as self-consistency technique by Wang et al., 2023) or you can ask your LLM to pick the best one. In OpenAI API, you can generate multiple responses for the same input by passing in the argument n (not an ideal API design if you ask me).

- Break one big prompt into smaller, simpler prompts.

Many tools promise to auto-optimize your prompts – they are quite expensive and usually just apply these tricks. One nice thing about these tools is that they’re no code, which makes them appealing to non-coders.

Cost and latency

Cost

The more explicit detail and examples you put into the prompt, the better the model performance (hopefully), and the more expensive your inference will cost.

OpenAI API charges for both the input and output tokens. Depending on the task, a simple prompt might be anything between 300 - 1000 tokens. If you want to include more context, e.g. adding your own documents or info retrieved from the Internet to the prompt, it can easily go up to 10k tokens for the prompt alone.

The cost with long prompts isn’t in experimentation but in inference.

Experimentation-wise, prompt engineering is a cheap and fast way get something up and running. For example, even if you use GPT-4 with the following setting, your experimentation cost will still be just over $300. The traditional ML cost of collecting data and training models is usually much higher and takes much longer.

- Prompt: 10k tokens ($0.06/1k tokens)

- Output: 200 tokens ($0.12/1k tokens)

- Evaluate on 20 examples

- Experiment with 25 different versions of prompts

The cost of LLMOps is in inference.

- If you use GPT-4 with 10k tokens in input and 200 tokens in output, it’ll be $0.624 / prediction.

- If you use GPT-3.5-turbo with 4k tokens for both input and output, it’ll be $0.004 / prediction or $4 / 1k predictions.

- As a thought exercise, in 2021, DoorDash ML models made 10 billion predictions a day. If each prediction costs $0.004, that’d be $40 million a day!

- By comparison, AWS personalization costs about $0.0417 / 1k predictions and AWS fraud detection costs about $7.5 / 1k predictions [for over 100,000 predictions a month]. AWS services are usually considered prohibitively expensive (and less flexible) for any company of a moderate scale.

Latency

Input tokens can be processed in parallel, which means that input length shouldn’t affect the latency that much.

However, output length significantly affects latency, which is likely due to output tokens being generated sequentially.

Even for extremely short input (51 tokens) and output (1 token), the latency for gpt-3.5-turbo is around 500ms. If the output token increases to over 20 tokens, the latency is over 1 second.

Here’s an experiment I ran, each setting is run 20 times. All runs happen within 2 minutes. If I do the experiment again, the latency will be very different, but the relationship between the 3 settings should be similar.

This is another challenge of productionizing LLM applications using APIs like OpenAI: APIs are very unreliable, and no commitment yet on when SLAs will be provided.

| # tokens | p50 latency (sec) | p75 latency | p90 latency |

| input: 51 tokens, output: 1 token | 0.58 | 0.63 | 0.75 |

| input: 232 tokens, output: 1 token | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.64 |

| input: 228 tokens, output: 26 tokens | 1.43 | 1.49 | 1.62 |

It is, unclear, how much of the latency is due to model, networking (which I imagine is huge due to high variance across runs), or some just inefficient engineering overhead. It’s very possible that the latency will reduce significantly in a near future.

While half a second seems high for many use cases, this number is incredibly impressive given how big the model is and the scale at which the API is being used. The number of parameters for gpt-3.5-turbo isn’t public but is guesstimated to be around 150B. As of writing, no open-source model is that big. Google’s T5 is 11B parameters and Facebook’s largest LLaMA model is 65B parameters. People discussed on this GitHub thread what configuration they needed to make LLaMA models work, and it seemed like getting the 30B parameter model to work is hard enough. The most successful one seemed to be randaller who was able to get the 30B parameter model work on 128 GB of RAM, which takes a few seconds just to generate one token.

The impossibility of cost + latency analysis for LLMs

The LLM application world is moving so fast that any cost + latency analysis is bound to go outdated quickly. Matt Ross, a senior manager of applied research at Scribd, told me that the estimated API cost for his use cases has gone down two orders of magnitude over the last 6 months. Latency has significantly decreased as well. Similarly, many teams have told me they feel like they have to do the feasibility estimation and buy (using paid APIs) vs. build (using open source models) decision every week.

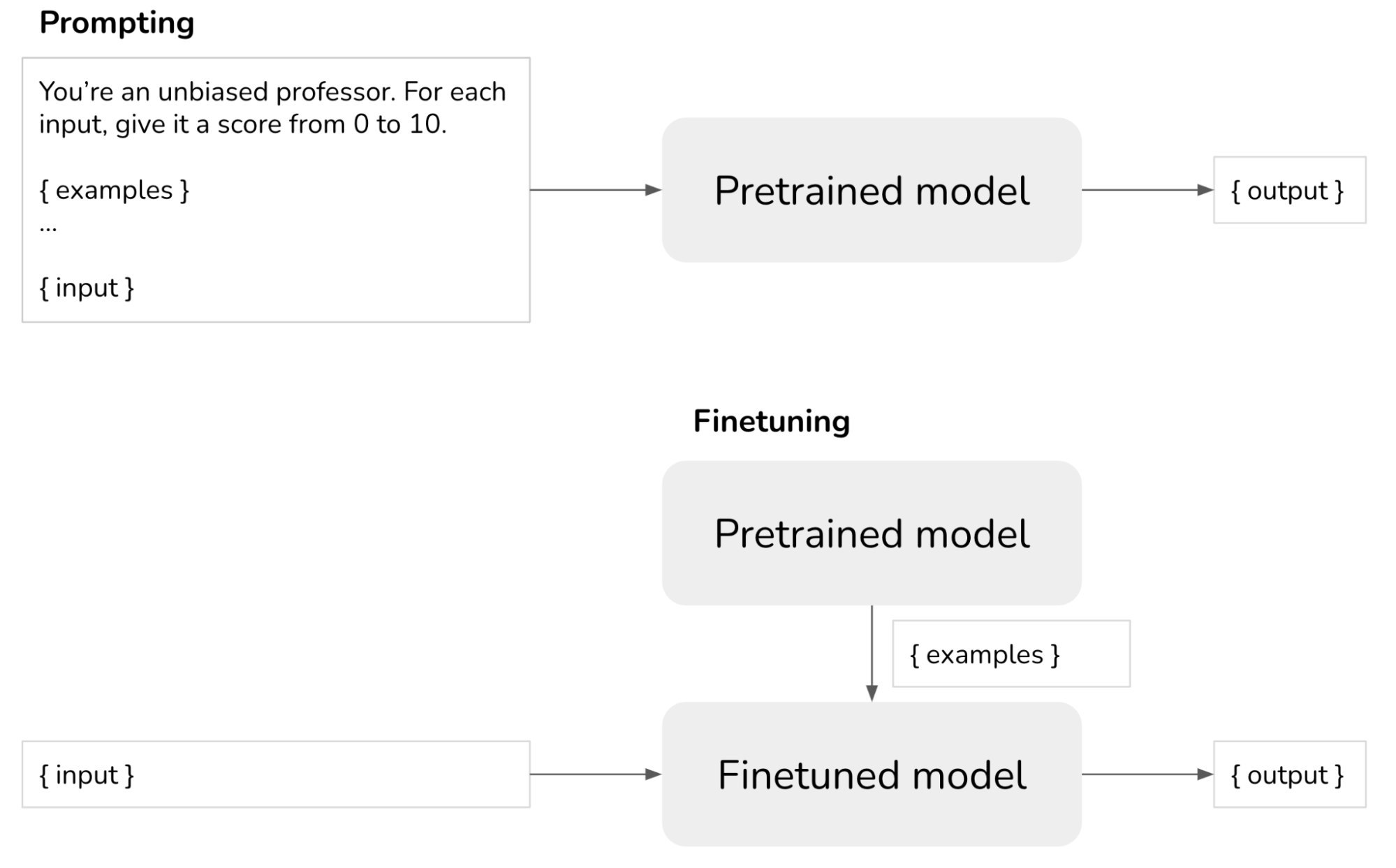

Prompting vs. finetuning vs. alternatives

- Prompting: for each sample, explicitly tell your model how it should respond.

- Finetuning: train a model on how to respond, so you don’t have to specify that in your prompt.

There are 3 main factors when considering prompting vs. finetuning: data availability, performance, and cost.

If you have only a few examples, prompting is quick and easy to get started. There’s a limit to how many examples you can include in your prompt due to the maximum input token length.

The number of examples you need to finetune a model to your task, of course, depends on the task and the model. In my experience, however, you can expect a noticeable change in your model performance if you finetune on 100s examples. However, the result might not be much better than prompting.

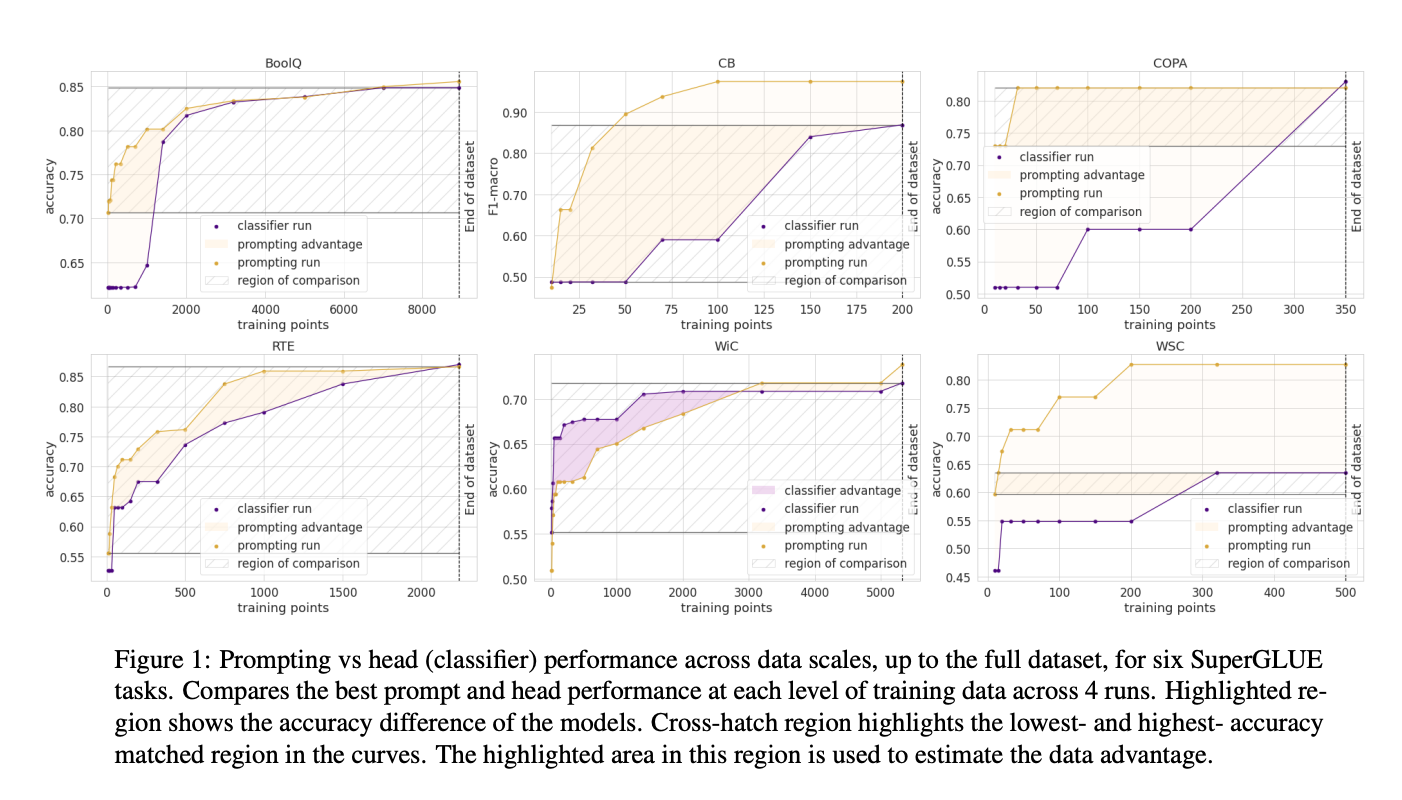

In How Many Data Points is a Prompt Worth? (2021), Scao and Rush found that a prompt is worth approximately 100 examples (caveat: variance across tasks and models is high – see image below). The general trend is that as you increase the number of examples, finetuning will give better model performance than prompting. There’s no limit to how many examples you can use to finetune a model.

The benefit of finetuning is two folds:

- You can get better model performance: can use more examples, examples becoming part of the model’s internal knowledge.

- You can reduce the cost of prediction. The more instruction you can bake into your mode, the less instruction you have to put into your prompt. Say, if you can reduce 1k tokens in your prompt for each prediction, for 1M predictions on gpt-3.5-turbo, you’d save $2000.

Prompt tuning

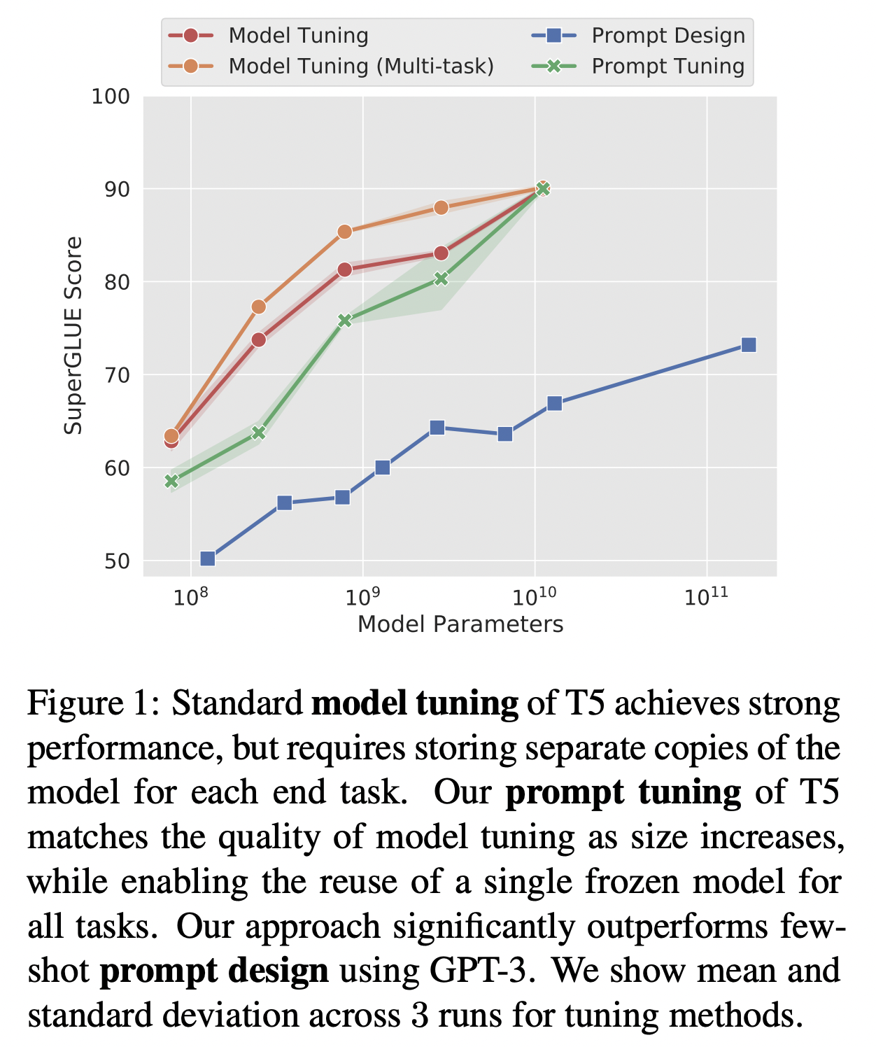

A cool idea that is between prompting and finetuning is prompt tuning, introduced by Leister et al. in 2021. Starting with a prompt, instead of changing this prompt, you programmatically change the embedding of this prompt. For prompt tuning to work, you need to be able to input prompts’ embeddings into your LLM model and generate tokens from these embeddings, which currently, can only be done with open-source LLMs and not in OpenAI API. On T5, prompt tuning appears to perform much better than prompt engineering and can catch up with model tuning (see image below).

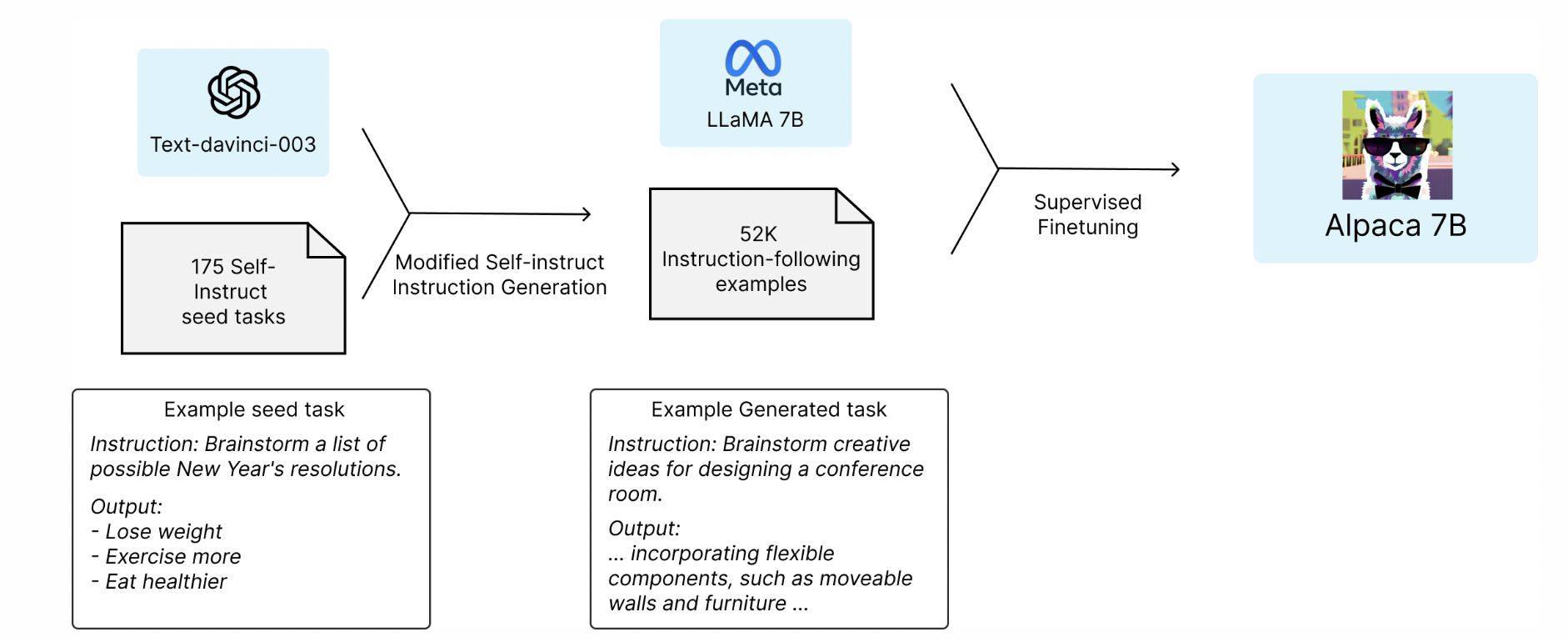

Finetuning with distillation

In March 2023, a group of Stanford students released a promising idea: finetune a smaller open-source language model (LLaMA-7B, the 7 billion parameter version of LLaMA) on examples generated by a larger language model (text-davinci-003 – 175 billion parameters). This technique of training a small model to imitate the behavior of a larger model is called distillation. The resulting finetuned model behaves similarly to text-davinci-003, while being a lot smaller and cheaper to run.

For finetuning, they used 52k instructions, which they inputted into text-davinci-003 to obtain outputs, which are then used to finetune LLaMa-7B. This costs under $500 to generate. The training process for finetuning costs under $100. See Stanford Alpaca: An Instruction-following LLaMA Model (Taori et al., 2023).

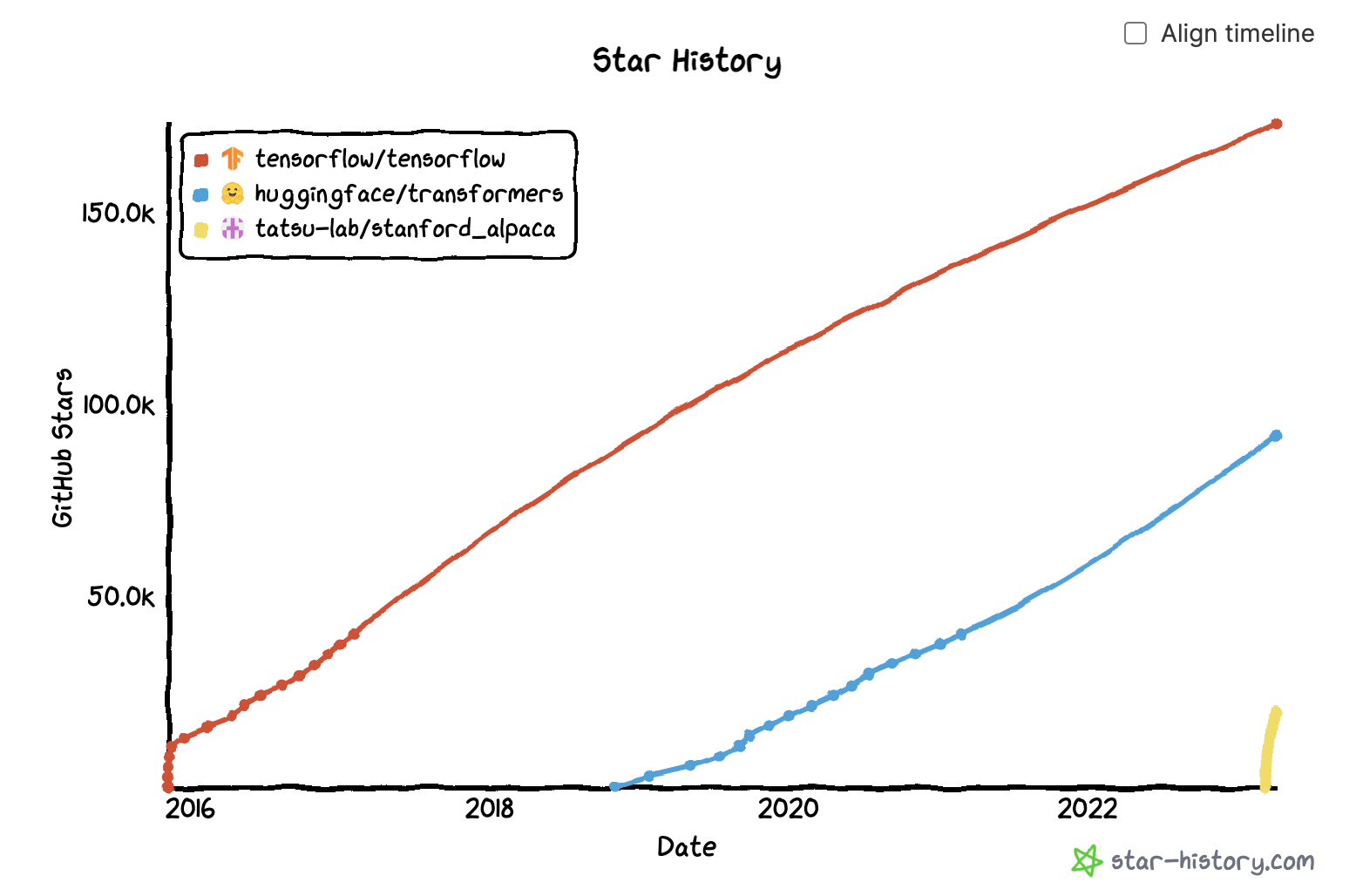

The appeal of this approach is obvious. After 3 weeks, their GitHub repo got almost 20K stars!! By comparison, HuggingFace’s transformers repo took over a year to achieve a similar number of stars, and TensorFlow repo took 4 months.

Embeddings + vector databases

One direction that I find very promising is to use LLMs to generate embeddings and then build your ML applications on top of these embeddings, e.g. for search and recsys. As of April 2023, the cost for embeddings using the smaller model text-embedding-ada-002 is $0.0004/1k tokens. If each item averages 250 tokens (187 words), this pricing means $1 for every 10k items or $100 for 1 million items.

While this still costs more than some existing open-source models, this is still very affordable, given that:

- You usually only have to generate the embedding for each item once.

- With OpenAI API, it’s easy to embeddings for queries and new items in real-time.

To learn more about using GPT embeddings, check out SGPT (Niklas Muennighoff, 2022) or this analysis on the performance and cost GPT-3 embeddings (Nils Reimers, 2022). Some of the numbers in Nils’ post are already outdated (the field is moving so fast!!), but the method is great!

The main cost of embedding models for real-time use cases is loading these embeddings into a vector database for low-latency retrieval. However, you’ll have this cost regardless of which embeddings you use. It’s exciting to see so many vector databases blossoming – the new ones such as Pinecone, Qdrant, Weaviate, Chroma as well as the incumbents Faiss, Redis, Milvus, ScaNN.

If 2021 was the year of graph databases, 2023 is the year of vector databases.

Backward and forward compatibility

Foundational models can work out of the box for many tasks without us having to retrain them as much. However, they do need to be retrained or finetuned from time to time as they go outdated. According to Lilian Weng’s Prompt Engineering post:

One observation with SituatedQA dataset for questions grounded in different dates is that despite LM (pretraining cutoff is year 2020) has access to latest information via Google Search, its performance on post-2020 questions are still a lot worse than on pre-2020 questions. This suggests the existence of some discrepencies or conflicting parametric between contextual information and model internal knowledge.

In traditional software, when software gets an update, ideally it should still work with the code written for its older version. However, with prompt engineering, if you want to use a newer model, there’s no way to guarantee that all your prompts will still work as intended with the newer model, so you’ll likely have to rewrite your prompts again. If you expect the models you use to change at all, it’s important to unit-test all your prompts using evaluation examples.

One argument I often hear is that prompt rewriting shouldn’t be a problem because:

- Newer models should only work better than existing models. I’m not convinced about this. Newer models might, overall, be better, but there will be use cases for which newer models are worse.

- Experiments with prompts are fast and cheap, as we discussed in the section Cost. While I agree with this argument, a big challenge I see in MLOps today is that there’s a lack of centralized knowledge for model logic, feature logic, prompts, etc. An application might contain multiple prompts with complex logic (discussed in Part 2. Task composability). If the person who wrote the original prompt leaves, it might be hard to understand the intention behind the original prompt to update it. This can become similar to the situation when someone leaves behind a 700-line SQL query that nobody dares to touch.

Another challenge is that prompt patterns are not robust to changes. For example, many of the published prompts I’ve seen start with “I want you to act as XYZ”. If OpenAI one day decides to print something like: “I’m an AI assistant and I can’t act like XYZ”, all these prompts will need to be updated.

Part 2. Task composability

Applications that consist of multiple tasks

The example controversy scorer above consists of one single task: given an input, output a controversy score. Most applications, however, are more complex. Consider the “talk-to-your-data” use case where we want to connect to a database and query this database in natural language. Imagine a credit card transaction table. You want to ask things like: "How many unique merchants are there in Phoenix and what are their names?" and your database will return: "There are 9 unique merchants in Phoenix and they are …".

One way to do this is to write a program that performs the following sequence of tasks:

- Task 1: convert natural language input from user to SQL query [LLM]

- Task 2: execute SQL query in the SQL database [SQL executor]

- Task 3: convert the SQL result into a natural language response to show user [LLM]

I did a small survey among people in my network and there doesn’t seem to be any consensus on terminologies, yet.

The word agent is being thrown around a lot to refer to an application that can execute multiple tasks according to a given control flow (see Control flows section). A task can leverage one or more tools. In the example above, SQL executor is an example of a tool.

Note: some people in my network resist using the term agent in this context as it is already overused in other contexts (e.g. agent to refer to a policy in reinforcement learning).

Other than SQL executor, here are more examples of tools:

- search (e.g. by using Google Search API or Bing API)

- web browser (e.g. given a URL, fetch its content)

- bash executor

- calculator

Tools and plugins are basically the same things. You can think of plugins as tools contributed to the OpenAI plugin store. As of writing, OpenAI plugins aren’t open to the public yet, but anyone can create and use tools.

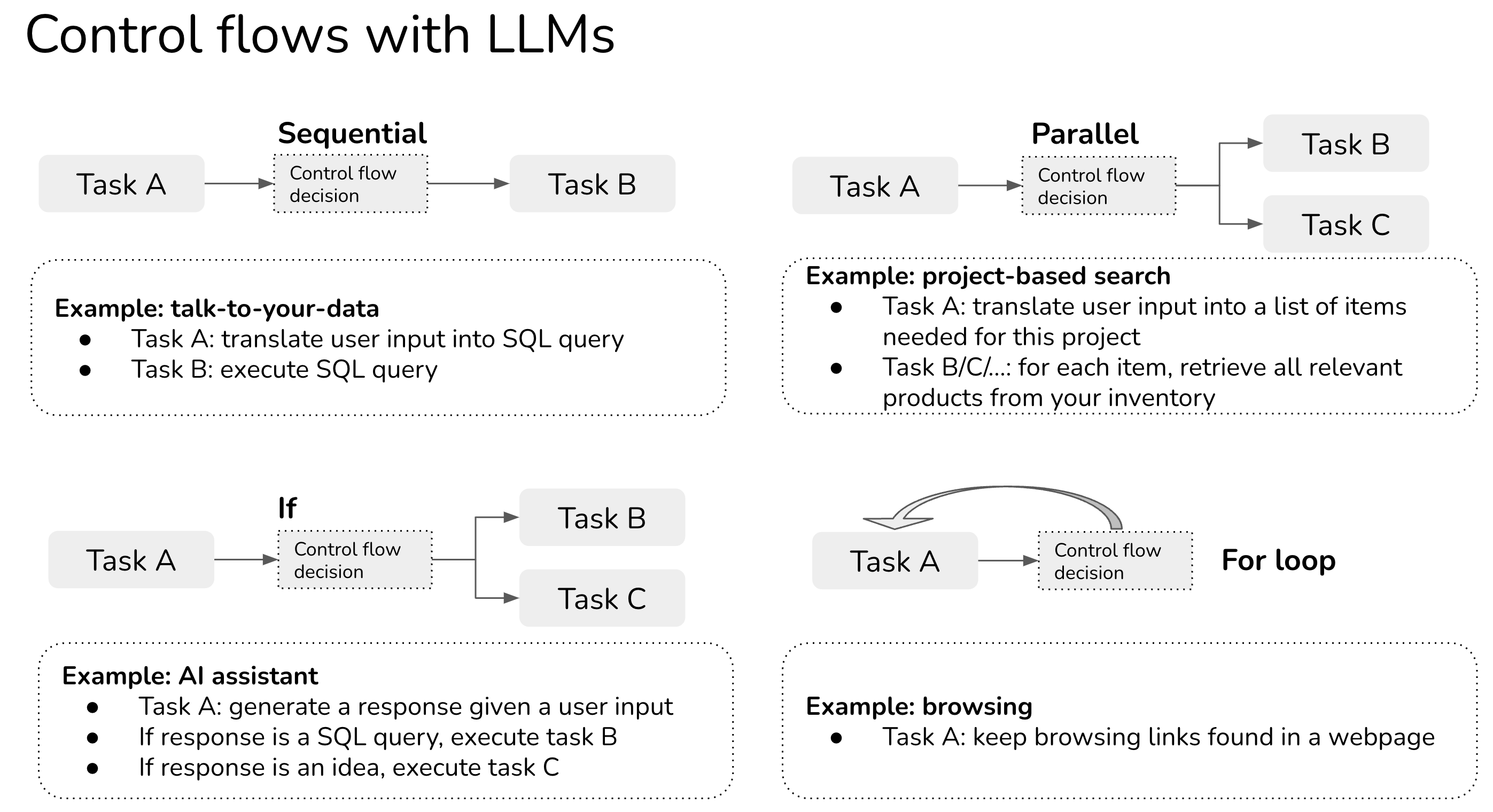

Control flows: sequential, parallel, if, for loop

In the example above, sequential is an example of a control flow in which one task is executed after another. There are other types of control flows such as parallel, if statement, for loop.

- Sequential: executing task B after task A completes, likely because task B depends on Task A. For example, the SQL query can only be executed after it’s been translated from the user input.

- Parallel: executing tasks A and B at the same time.

- If statement: executing task A or task B depending on the input.

- For loop: repeat executing task A until a certain condition is met. For example, imagine you use browser action to get the content of a webpage and keep on using browser action to get the content of links found in that webpage until the agent feels like it’s got sufficient information to answer the original question.

Note: while parallel can definitely be useful, I haven’t seen a lot of applications using it.

Control flow with LLM agents

In traditional software engineering, conditions for control flows are exact. With LLM applications (also known as agents), conditions might also be determined by prompting.

For example, if you want your agent to choose between two actions search, SQL executor, and Chat, you might explain how it should choose one of these actions as follows (very approximate), In other words, you can use LLMs to decide the condition of the control flow!

You have access to three tools: Search, SQL executor, and Chat.

Search is useful when users want information about current events or products.

SQL executor is useful when users want information that can be queried from a database.

Chat is useful when users want general information.

Provide your response in the following format:

Input: { input }

Thought: { thought }

Action: { action }

Action Input: { action_input }

Observation: { action_output }

Thought: { thought }

Testing an agent

For agents to be reliable, we’d need to be able to build and test each task separately before combining them. There are two major types of failure modes:

- One or more tasks fail. Potential causes:

- Control flow is wrong: a non-optional action is chosen

- One or more tasks produce incorrect results

- All tasks produce correct results but the overall solution is incorrect. Press et al. (2022) call this “composability gap”: the fraction of compositional questions that the model answers incorrectly out of all the compositional questions for which the model answers the sub-questions correctly.

Like with software engineering, you can and should unit test each component as well as the control flow. For each component, you can define pairs of (input, expected output) as evaluation examples, which can be used to evaluate your application every time you update your prompts or control flows. You can also do integration tests for the entire application.

Part 3. Promising use cases

The Internet has been flooded with cool demos of applications built with LLMs. Here are some of the most common and promising applications that I’ve seen. I’m sure that I’m missing a ton.

For more ideas, check out the projects from two hackathons I’ve seen:

AI assistant

This is hands down the most popular consumer use case. There are AI assistants built for different tasks for different groups of users – AI assistants for scheduling, making notes, pair programming, responding to emails, helping with parents, making reservations, booking flights, shopping, etc. – but, of course, the ultimate goal is an assistant that can assist you in everything.

This is also the holy grail that all big companies are working towards for years: Google with Google Assistant and Bard, Facebook with M and Blender, OpenAI (and by extension, Microsoft) with ChatGPT. Quora, which has a very high risk of being replaced by AIs, released their own app Poe that lets you chat with multiple LLMs. I’m surprised Apple and Amazon haven’t joined the race yet.

Chatbot

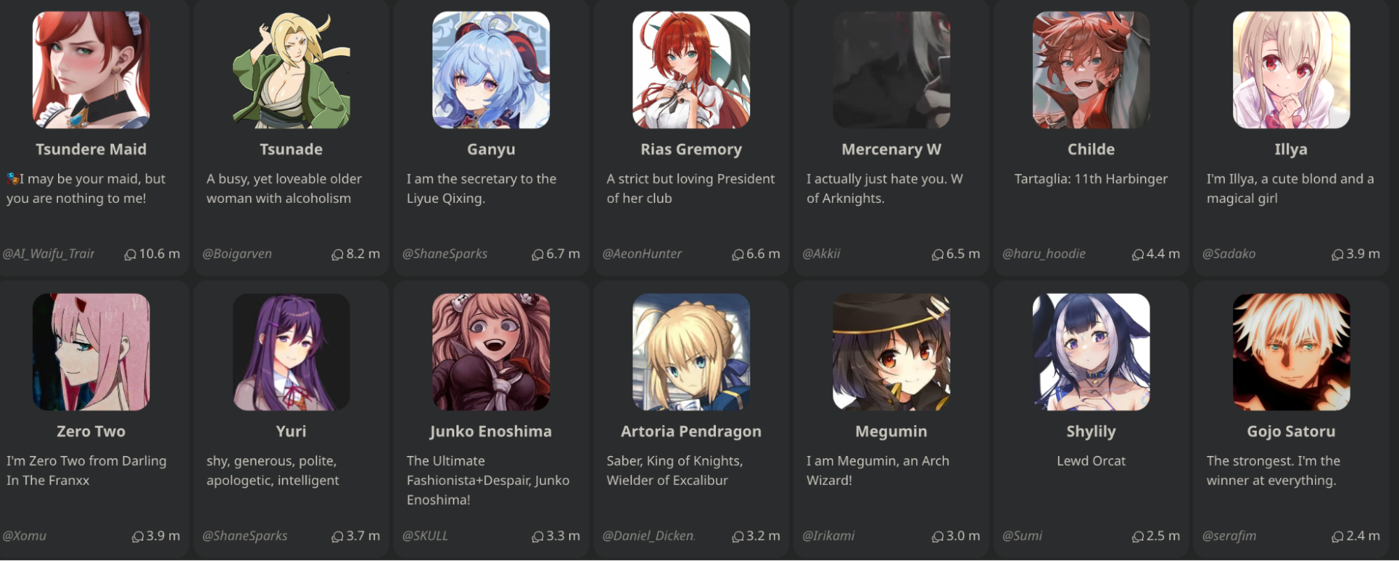

Chatbots are similar to AI assistants in terms of APIs. If AI assistants’ goal is to fulfill tasks given by users, whereas chatbots’ goal is to be more of a companion. For example, you can have chatbots that talk like celebrities, game/movie/book characters, businesspeople, authors, etc.

Michelle Huang used her childhood journal entries as part of the prompt to GPT-3 to talk to the inner child.

The most interesting company in the consuming-chatbot space is probably Character.ai. It’s a platform for people to create and share chatbots. The most popular types of chatbots on the platform, as writing, are anime and game characters, but you can also talk to a psychologist, a pair programming partner, or a language practice partner. You can talk, act, draw pictures, play text-based games (like AI Dungeon), and even enable voices for characters. I tried a few popular chatbots – none of them seem to be able to hold a conversation yet, but we’re just at the beginning. Things can get even more interesting if there’s a revenue-sharing model so that chatbot creators can get paid.

Programming and gaming

This is another popular category of LLM applications, as LLMs turn out to be incredibly good at writing and debugging code. GitHub Copilot is a pioneer (whose VSCode extension has had 5 million downloads as of writing). There have been pretty cool demos of using LLMs to write code:

- Create web apps from natural languages

- Find security threats: Socket AI examines npm and PyPI packages in your codebase for security threats. When a potential issue is detected, they use ChatGPT to summarize findings.

- Gaming

- Create games: e.g. Wyatt Cheng has an awesome video showing how he used ChatGPT to clone Flappy Bird.

- Generate game characters.

- Let you have more realistic conversations with game characters: check out this awesome demo by Convai!

Learning

Whenever ChatGPT was down, OpenAI discord is flooded with students complaining about not being to complete their homework. Some responded by banning the use of ChatGPT in school altogether. Some have a much better idea: how to incorporate ChatGPT to help students learn even faster. All EdTech companies I know are going full-speed on ChatGPT exploration.

Some use cases:

- Summarize books

- Automatically generate quizzes to make sure students understand a book or a lecture. Not only ChatGPT can generate questions, but it can also evaluate whether a student’s input answers are correct.

- I tried and ChatGPT seemed pretty good at generating quizzes for Designing Machine Learning Systems. Will publish the quizzes generated soon!

- Grade / give feedback on essays

- Walk through math solutions

- Be a debate partner: ChatGPT is really good at taking different sides of the same debate topic.

With the rise of homeschooling, I expect to see a lot of applications of ChatGPT to help parents homeschool.

Talk-to-your-data

This is, in my observation, the most popular enterprise application (so far). Many, many startups are building tools to let enterprise users query their internal data and policies in natural languages or in the Q&A fashion. Some focus on verticals such as legal contracts, resumes, financial data, or customer support. Given a company’s all documentations, policies, and FAQs, you can build a chatbot that can respond your customer support requests.

The main way to do this application usually involves these 4 steps:

- Organize your internal data into a database (SQL database, graph database, embedding/vector database, or just text database)

- Given an input in natural language, convert it into the query language of the internal database. For example, if it’s a SQL or graph database, this process can return a SQL query. If it’s embedding database, it’s might be an ANN (approximate nearest neighbor) retrieval query. If it’s just purely text, this process can extract a search query.

- Execute the query in the database to obtain the query result.

- Translate this query result into natural language.

While this makes for really cool demos, I’m not sure how defensible this category is. I’ve seen startups building applications to let users query on top of databases like Google Drive or Notion, and it feels like that’s a feature Google Drive or Notion can implement in a week.

OpenAI has a pretty good tutorial on how to talk to your vector database.

Can LLMs do data analysis for me?

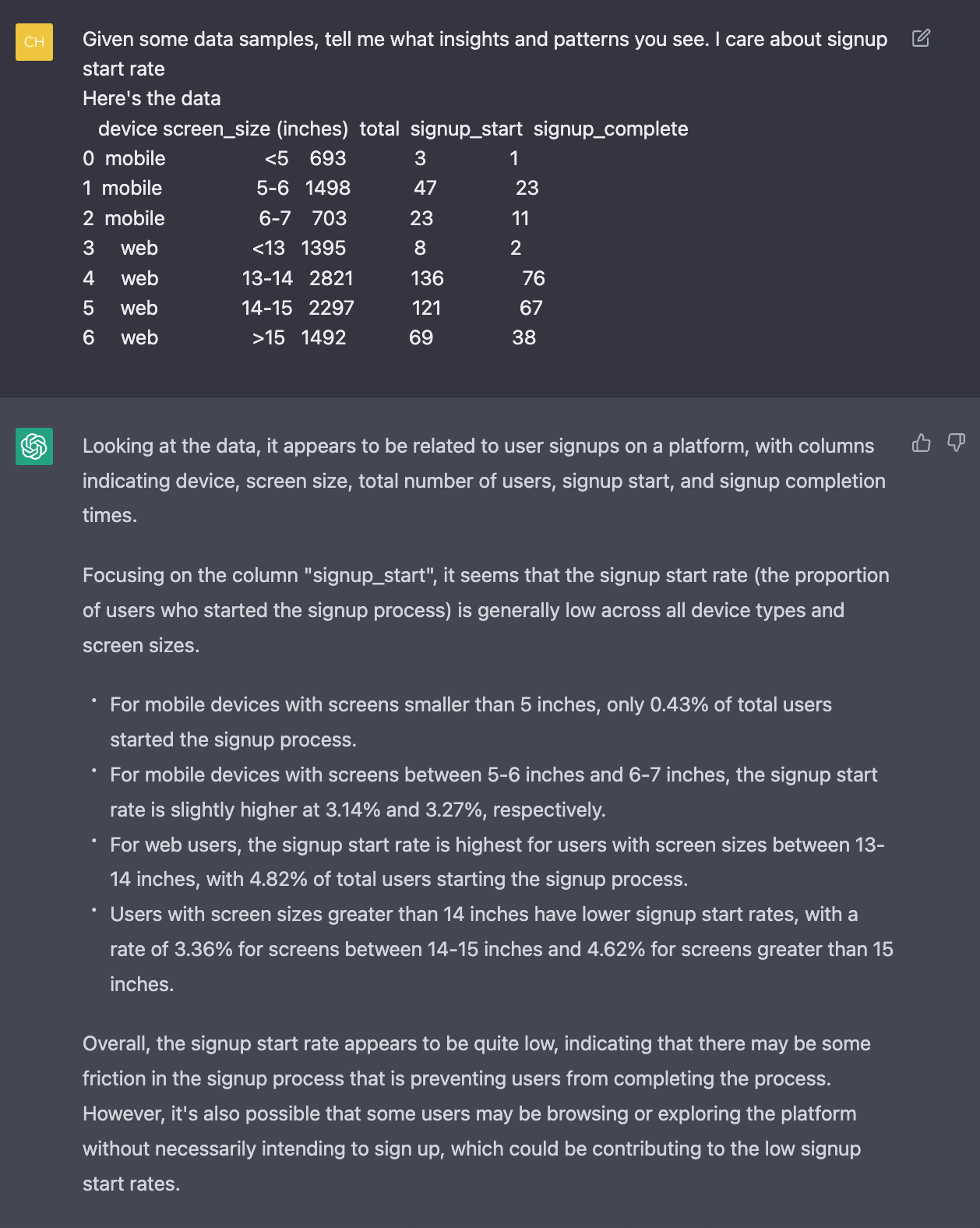

I tried inputting some data into gpt-3.5-turbo, and it seems to be able to detect some patterns. However, this only works for small data that can fit into the input prompt. Most production data is larger than that.

Search and recommendation

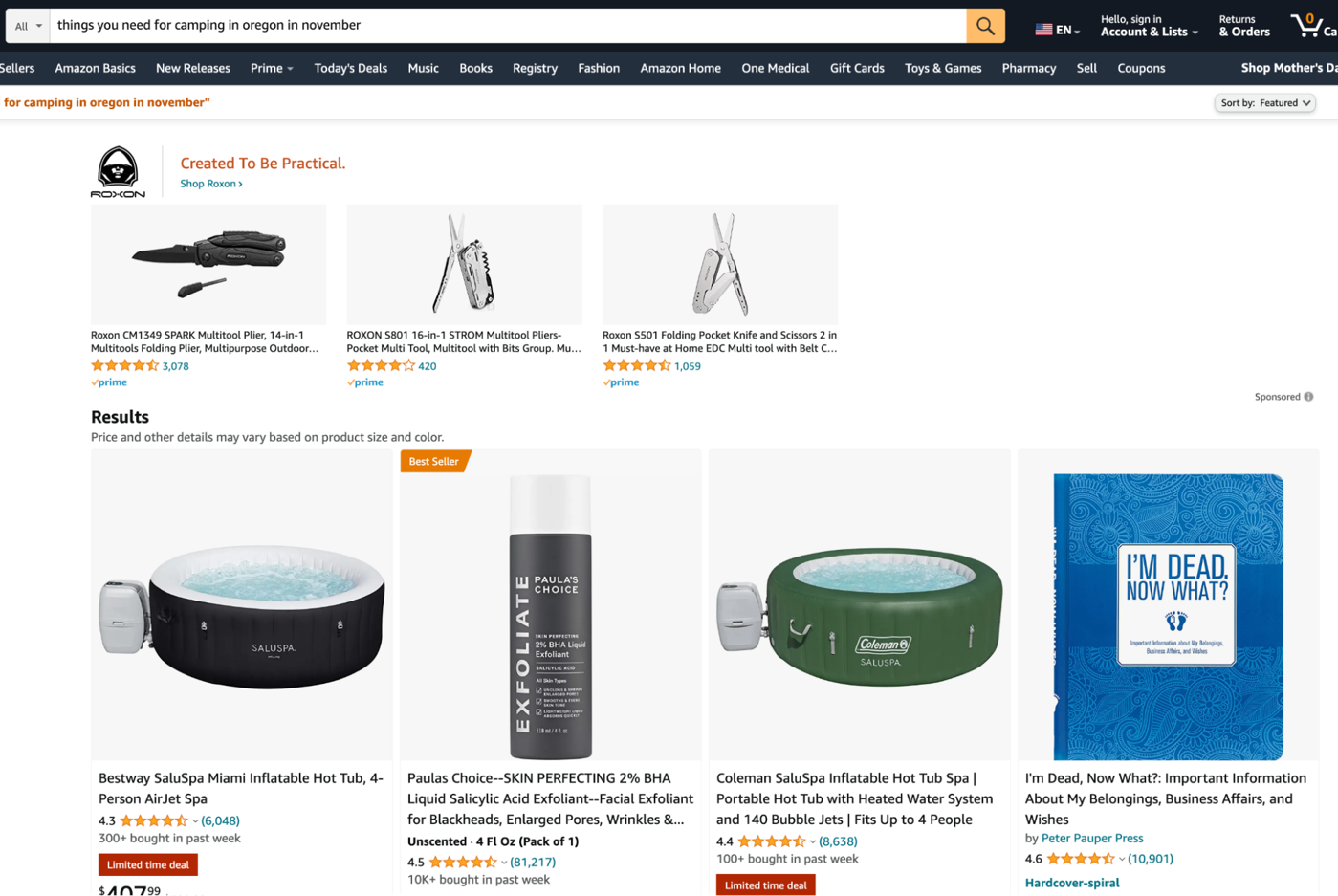

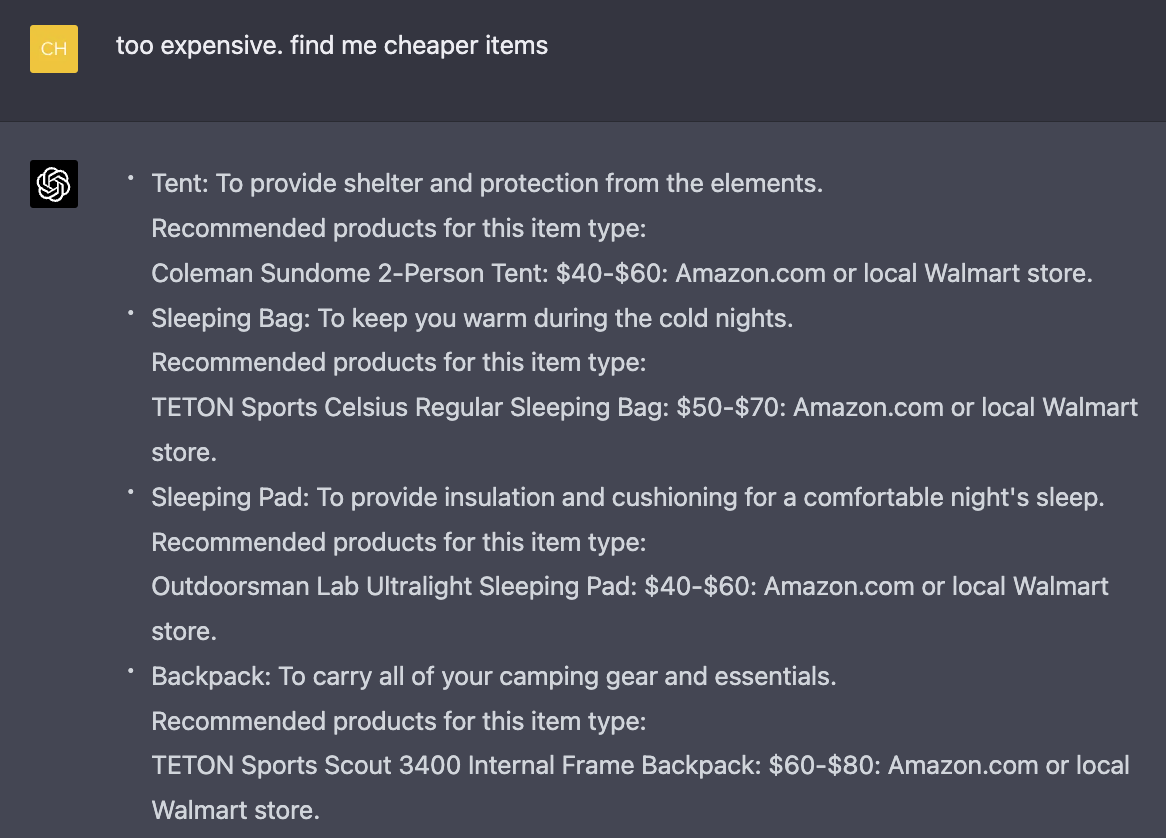

Search and recommendation has always been the bread and butter of enterprise use cases. It’s going through a renaissance with LLMs. Search has been mostly keyword-based: you need a tent, you search for a tent. But what if you don’t know what you need yet? For example, if you’re going camping in the woods in Oregon in November, you might end up doing something like this:

- Search to read about other people’s experiences.

- Read those blog posts and manually extract a list of items you need.

- Search for each of these items, either on Google or other websites.

If you search for “things you need for camping in oregon in november” directly on Amazon or any e-commerce website, you’ll get something like this:

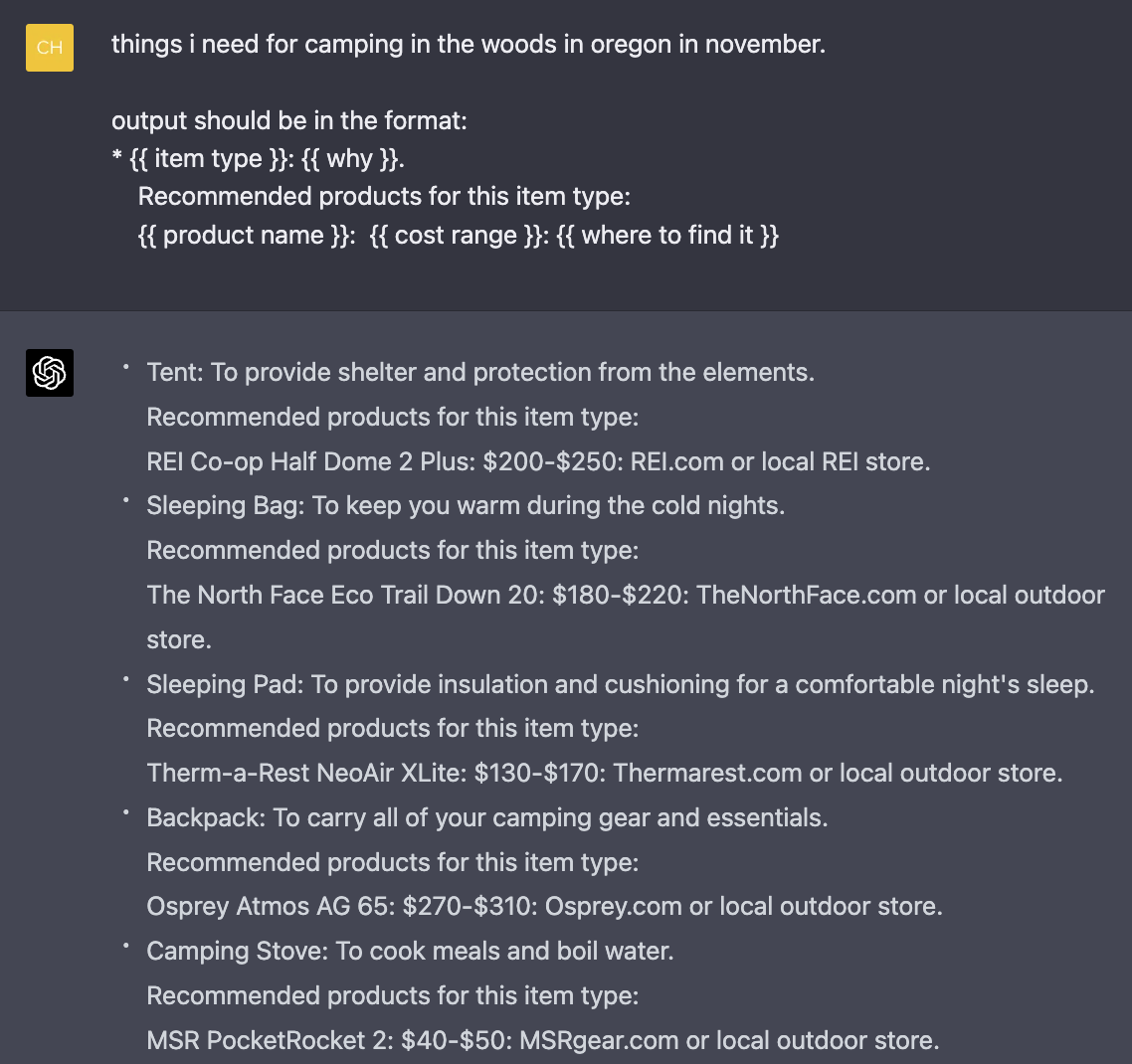

But what if searching for “things you need for camping in oregon in november” on Amazon actually returns you a list of things you need for your camping trip?

It’s possible today with LLMs. For example, the application can be broken into the following steps:

- Task 1: convert the user query into a list of product names [LLM]

- Task 2: for each product name in the list, retrieve relevant products from your product catalog.

If this works, I wonder if we’ll have LLM SEO: techniques to get your products recommended by LLMs.

Sales

The most obvious way to use LLMs for sales is to write sales emails. But nobody really wants more or better sales emails. However, several companies in my network are using LLMs to synthesize information about a company to see what they need.

SEO

SEO is about to get very weird. Many companies today rely on creating a lot of content hoping to rank high on Google. However, given that LLMs are REALLY good at generating content, and I already know a few startups whose service is to create unlimited SEO-optimized content for any given keyword, search engines will be flooded. SEO might become even more of a cat-and-mouse game: search engines come up with new algorithms to detect AI-generated content, and companies get better at bypassing these algorithms. People might also rely less on search, and more on brands (e.g. trust only the content created by certain people or companies).

And we haven’t even touched on SEO for LLMs yet: how to inject your content into LLMs’ responses!!

Conclusion

We’re still in the early days of LLMs applications – everything is evolving so fast. I recently read a book proposal on LLMs, and my first thought was: most of this will be outdated in a month. APIs are changing day to day. New applications are being discovered. Infrastructure is being aggressively optimized. Cost and latency analysis needs to be done on a weekly basis. New terminologies are being introduced.

Not all of these changes will matter. For example, many prompt engineering papers remind me of the early days of deep learning when there were thousands of papers describing different ways to initialize weights. I imagine that tricks to tweak your prompts like: "Answer truthfully", "I want you to act like …", writing "question: " instead of "q:" wouldn’t matter in the long run.

Given that LLMs seem to be pretty good at writing prompts for themselves – see Large Language Models Are Human-Level Prompt Engineers (Zhou et al., 2022) – who knows that we’ll need humans to tune prompts?

However, given so much happening, it’s hard to know which will matter, and which won’t.

I recently asked on LinkedIn how people keep up to date with the field. The strategy ranges from ignoring the hype to trying out all the tools.

-

Ignore (most of) the hype

Vicki Boykis (Senior ML engineer @ Duo Security): I do the same thing as with any new frameworks in engineering or the data landscape: I skim the daily news, ignore most of it, and wait six months to see what sticks. Anything important will still be around, and there will be more survey papers and vetted implementations that help contextualize what’s happening.

-

Read only the summaries

Shashank Chaurasia (Engineering @ Microsoft): I use the Creative mode of BingChat to give me a quick summary of new articles, blogs and research papers related to Gen AI! I often chat with the research papers and github repos to understand the details.

-

Try to keep up to date with the latest tools

Chris Alexiuk (Founding ML engineer @ Ox): I just try and build with each of the tools as they come out - that way, when the next step comes out, I’m only looking at the delta.

What’s your strategy?

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/jLnuQE2

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.