Note: This article is also available in Korean.

On our tour of South Korea’s so-called security applications we’ve already took a look at TouchEn nxKey, an application meant to combat keyloggers by … checks notes … making keylogging easier. Today I want to shed some light on another application that many people in South Korea had to install on their computers: IPinside LWS Agent by Interezen.

The stated goal of the application is retrieving your “real” IP address to prevent online fraud. I found however that it collects way more data. And while it exposes this trove of data to any website asking politely, it doesn’t look like it is all too helpful for combating actual fraud.

Contents

How does it work?

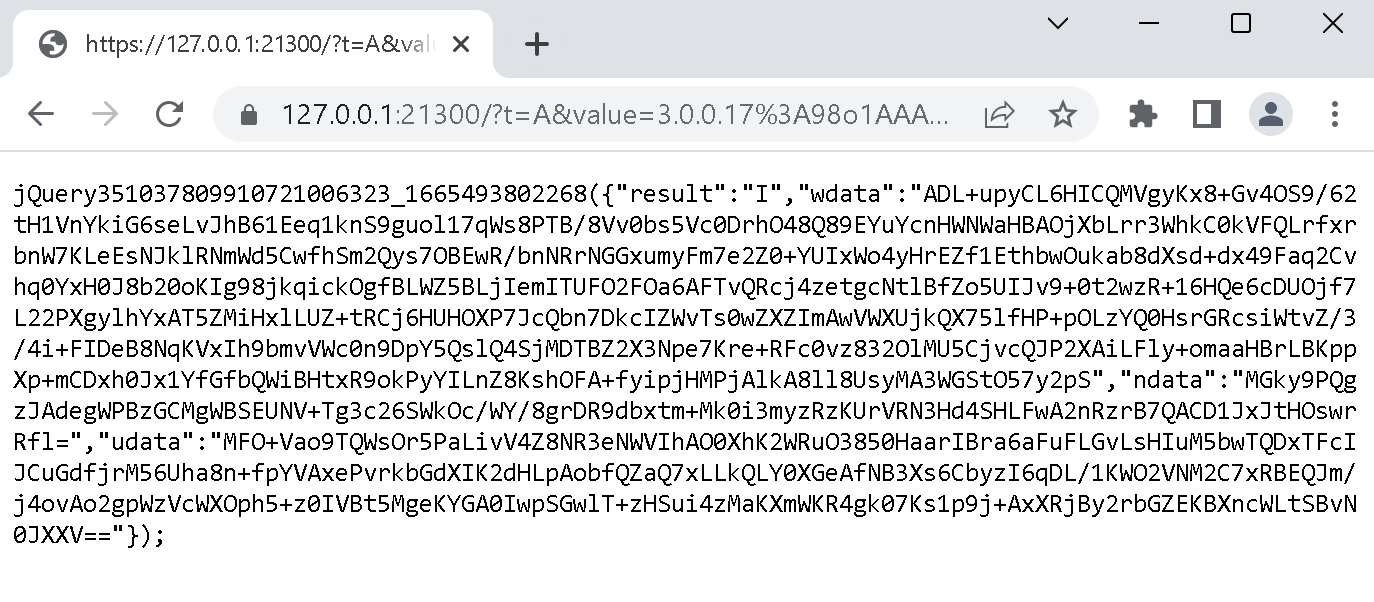

Similarly to TouchEn nxKey, the IPinside LWS Agent application also communicates with websites via a local web server. When a banking website in South Korea wants to learn more about you, it will make a JSONP request to localhost:21300. If this request fails, the banking website will deny entry and ask that you install IPinside LWS Agent first. So in South Korea running this application isn’t optional.

On the other hand, if the application is present the website will receive various pieces of data in the wdata, ndata and udata fields. Quite a bit of data actually:

This data is supposed to contain your IP address. But even from the size of it, it’s obvious that it cannot be only that. In fact, there is a whole lot more data being transmitted.

What data is it?

wdata

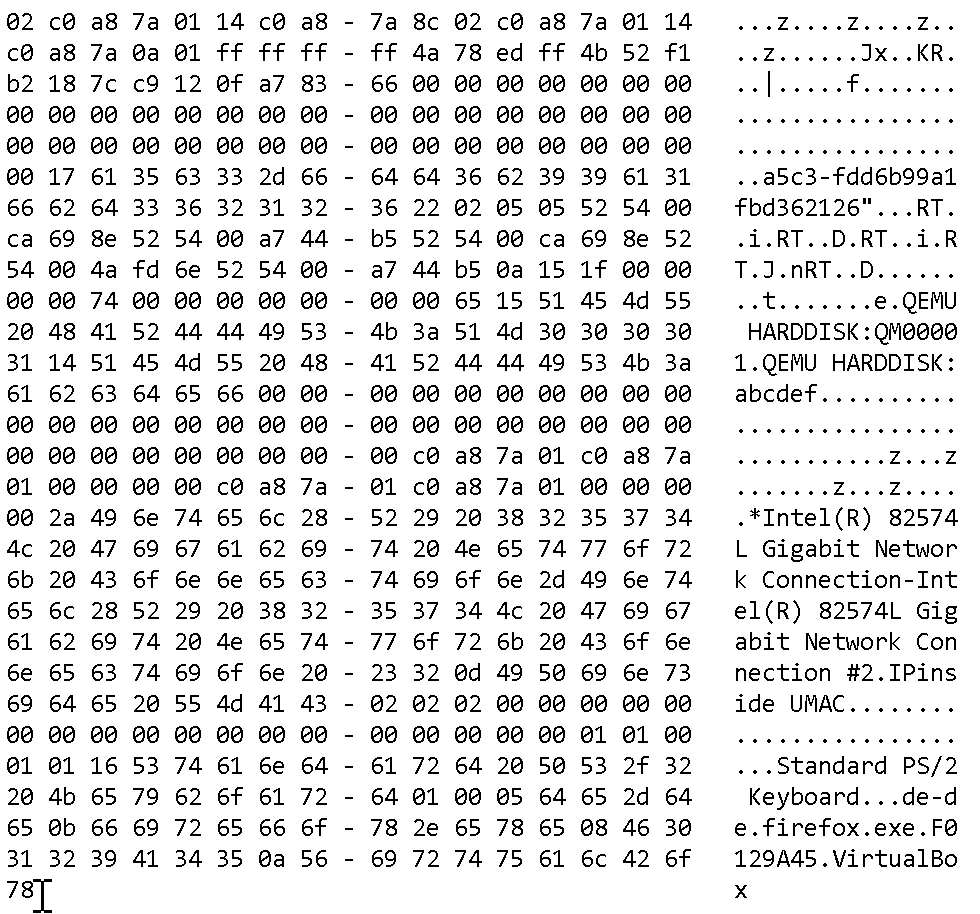

Let’s start with wdata which is the most interesting data structure here. When decrypted, you get a considerable amount of binary data:

As you can see from the output, I am running IPinside in a virtual machine. It even says VirtualBox at the end of the output, even though this particular machine is no longer running on VirtualBox.

Another obvious thing are the two hard drives of my virtual machine, one with the serial number QM00001 and another with the serial number abcdef. That F0129A45 is the serial number of the primary hard drive volume. You can also see my two network cards, both listed as Intel(R) 82574L Gigabit Network Connection. There is my keyboard model (Standard PS/2 Keyboard) and keyboard layout (de-de).

And if you look closely, you’ll even notice the byte sequences c0 a8 7a 01 (standing for my gateway’s IP address 192.168.122.1), c0 a8 7a 8c (192.168.122.140, the local IP address of the first network card) and c0 a8 7a 0a (192.168.122.10, the local IP address of the second network card).

But there is way more. For example, that 65 (letter e) right before the hard drive information is the result of calling GetProductInfo() function and indicates that I’m running Windows 10 Home. And 74 (letter t) before it encodes my exact Windows version.

Information about running processes

One piece of the data is particularly interesting. Don’t you wonder where the firefox.exe comes from here? It indicates that the Mozilla Firefox process is running in the background. This information is transmitted despite the active application being Google Chrome.

See, websites give IPinside agent a number of parameters that determine the output produced. One such parameter is called winRemote. It’s mildly obfuscated, but after removing the obfuscation you get:

TeamViewer_Desktop.exe|rcsemgru.exe|rcengmgru.exe|teamviewer_Desktop.exe

So banking websites are interested in whether you are running remote access tools. If a process is detected that matches one of these strings, the match is added to the wdata response.

And of course this functionality isn’t limited to searching for remote access tools. I replaced the winRemote parameter by AGULAAAAAAtmaXJlZm94LmV4ZQA= and got the information back whether Firefox is currently running. So this can be abused to look for any applications of interest.

And even that isn’t the end of it. IPinside agent will match substrings as well! So it can tell you whether a process with fire in its name is currently running.

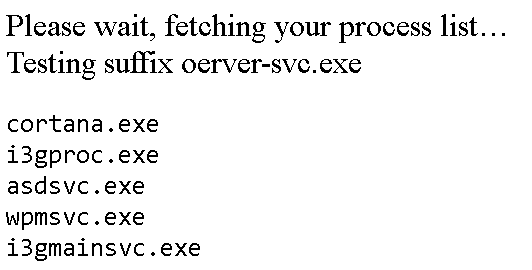

That is enough for a website to start searching your process list without knowing what these processes could be. I created a page that would start with the .exe suffix and do a depth-first search. The issue here was mostly IPinside response being so slow, each request taking half a second. I slightly optimized the performance by testing multiple guesses with one request and got a proof of concept page that would turn up a process name every 40-50 seconds:

With sufficient time, this page could potentially enumerate every process running on the system.

ndata

The ndata part of the response is much simpler. It looks like this:

��HDATAIP=▚▚▚.▚▚▚.▚▚▚.▚▚▚��VD1NATIP=▚▚▚.▚▚▚.▚▚▚.▚▚▚��VD1CLTIP=192.168.122.140��VD2NATIP=��VD2CLTIP=192.168.122.10��VPN=2��ETHTYPE=ETH1

No, I didn’t mess up decoding the data. Yes, � is really in the response. The idea here was actually to use ∽ (reverse tilde symbol) as a separator. But since my operating system isn’t Korean, the character encoding for non-Unicode applications (like IPinside LWS Agent) isn’t set to EUC-KR. The application doesn’t expect this and botches the conversion to UTF-8.

▚▚▚.▚▚▚.▚▚▚.▚▚▚ on the other hand was me censoring my public IP address. The application gets it by two different means. VD1NATIP appears to come from my home router.

HDATAIP on the other hand comes from a web server. Which web server? That’s determined by the host_info parameter that the website provides to the application. It is also obfuscated, the actual value is:

https://ift.tt/px93ykI

Only the first two parts appear to be used, the application makes a request to http://www.securetrueip.co.kr:80/androidagent.jsc. One of the response headers is RESPONSE_IP. You guessed it: that’s your IP address as this web server sees it.

The application uses low-level WS2_32.DLL APIs here, probably as an attempt to prevent this traffic from being routed through some proxy server or VPN. After all, the goal is deanonymizing you.

udata

Finally, there is udata where “u” stands for “unique.” There are several different output types here, this is type 13:

[52-54-00-A7-44-B5:1:0:Intel(R) 82574L Gigabit Network Connection];[52-54-00-4A-FD-6E:0:0:Intel(R) 82574L Gigabit Network Connection #2];$[QM00001:QEMU HARDDISK:];[abcdef:QEMU HARDDISK:];[::];[::];[::];

Once again a list of network cards and hard drives, but this time MAC addresses of the network cards are listed as well. Other output types are mostly the same data in different formats, except for type 30. This one contains a hexadecimal CPU identifier, representing 16 bytes generated by mashing together the results of 15 different CPUID calls.

How is this data protected?

So there is a whole lot of data which allows deanonymizing users, learning about the hardware and software they use, potentially facilitating further attacks by exposing which vulnerabilities are present on their systems. Surely this kind of data is well-protected, right? I mean: sure, every Korean online banking website has access to it. And Korean government websites. And probably more Interezen customers. But nobody else, right?

Well, the server under localhost:21300 doesn’t care who it responds to. Any website can request the data. But it still needs to know how to decode it.

When talking about wdata, there are three layers of protection being applied: obfuscation, compression and encryption. Yes, obfuscating data by XOR’ing it with a single random byte probably isn’t adding much protection. And compression doesn’t really count as protection either if people can easily find the well-known GPL-licensed source code that Interezen used without complying with the license terms. But there is encryption, and it is even using public-key cryptography!

So the application only contains the public RSA key, that’s not sufficient to decrypt the data. The private key is only known to Interezen. And any of their numerous customers. Let’s hope that all these customers sufficiently protect this private key and don’t leak it to some hackers.

Otherwise RSA encryption can be considered secure even with moderately sized keys. Except… we aren’t talking about a moderately sized key here. We aren’t even talking about a weak key. We are talking about a 320 bits key. That’s shorter than the very first key factored in the RSA Factoring Challenge. And that was in April 1991, more than three decades ago. Sane RSA libraries don’t even work with keys this short.

I downloaded msieve and let it run on my laptop CPU, occupying a single core of it:

$ ./msieve 108709796755756429540066787499269637…

sieving in progress (press Ctrl-C to pause)

86308 relations (21012 full + 65296 combined from 1300817 partial), need 85977

sieving complete, commencing postprocessing

linear algebra completed 80307 of 82231 dimensions (97.7%, ETA 0h 0m)

elapsed time 02:36:55

Yes, it took me 2 hours and 36 minutes to calculate the private key on very basic hardware. That’s how much protection this RSA encryption provides.

When talking about ndata and udata, things look even more dire. The only protection layer here is encryption. No, not public-key cryptography but symmetric encryption via AES-256. And of course the encryption key is hardcoded in the application, there is no other way.

To add insult to injury, the application produces identical ciphertext on each run. At first I thought this to be the result of the deprecated ECB block chaining mode being used. But: no, the application uses CBC block chaining mode. But it fails to pass in an initialization vector, so the cryptography library in question always fills the initialization vector with zeroes.

Which is a long and winded way of saying: the encryption would be broken regardless of whether one can retrieve the encryption key from the application.

To sum up: no, this data isn’t really protected. If the user has the IPinside LWS Agent installed, any website can access the data it collects. The encryption applied is worthless.

And the overall security of the application?

That web server the application runs on port 21300, what is it? Turns out, it’s their own custom code doing it, built on low-level network sockets functionality. That’s perfectly fine of course, who hasn’t built their own rudimentary web server using substring matches to parse requests and deployed it to millions of users?

Their web server still needs SSL support, so it relies on the OpenSSL library for that. Which library version? Why, OpenSSL 1.0.1j of course. Yes, it was released more than eight years ago. Yes, end of support for OpenSSL 1.0.1 was six years ago. Yes, there were 11 more releases on the 1.0.1 branch after 1.0.1j, with numerous vulnerabilities fixed, and not even these fixes made it into IPinside LWS Agent.

Sure, that web server is also single-threaded, why wouldn’t it be? It’s not like people will open two banking websites in parallel. Yes, this makes it trivial for a malicious website to lock up that server with long-running requests (denial-of-service attack). But that merely prevents people from logging into online banking and government websites, not a big deal.

Looking at how this server is implemented, there is code that essentially looks like this:

BYTE inputBuffer[8192];

char request[8192];

char debugString[8192];

memset(inputBuffer, 0, sizeof(inputBuffer));

memset(request, 0, sizeof(request));

int count = ssl_read(ssl, inputBuffer, sizeof(inputBuffer));

if (count <= 0)

{

…

}

memcpy(request, inputBuffer, count);

memset(debugString, 0, sizeof(debugString));

sprintf(debugString, "Received data from SSL socket: %s", request);

log(debugString);

handle_request(request);

Can you spot the issues with this code?

…

Come on, I’m waiting.

…

Yes, I’m cheating. Unlike you I actually debugged that code and saw live just how badly things went here.

…

First of all, it can happen that ssl_read will produce exactly 8192 bytes and fill the entire buffer. In that case, inputBuffer won’t be null-terminated. And its copy in request won’t be null-terminated either. So attempting to use request as a null-terminated string in sprintf() or handle_request() will read beyond the end of the buffer. In fact, with the memory layout here it will continue into the identical inputBuffer memory area and then into whatever comes after it.

So the sprintf() call actually receives more than 16384 bytes of data, and its target buffer won’t be nearly large enough for that. But even if this data weren’t missing the terminating zero: taking a 8192 byte string, adding a bunch more text to it and trying to squeeze the result into a 8192 byte buffer isn’t going to work.

This isn’t an isolated piece of bad code. While researching the functionality of this application, I couldn’t fail noticing several more stack buffer overflows and another buffer over-read. To my (very limited) knowledge of binary exploitation, these vulnerabilities cannot be turned into Remote Code Execution thanks to StackGuard and SafeSEH protection mechanisms being active and effective. If somebody more experienced finds a way around that however, things will get very ugly. The application has neither ASLR nor DEP protection enabled.

Some of these vulnerabilities can definitely crash the application however. I created two proof of concept pages which did so repeatedly. And that’s another denial-of-service attack, also effectively preventing people from using online banking in South Korea.

When will it be fixed?

I submitted three vulnerability reports to KrCERT on October 21st, 2022. By November 14th KrCERT confirmed forwarding all these reports to Interezen. I did not receive any communication after that.

Prior to this disclosure, a Korean reporter asked Interezen to comment. They confirmed receiving my reports but claimed that they only received one of them on January 6th, 2023. Supposedly because of that they plan to release their fix in February, at which point it would be up to their customers (meaning: banks and such) to distribute the new version to the users.

Like other similar applications, this software won’t autoupdate. So users will need to either download and install an update manually or perform an update via a management application like Wizvera Veraport. Neither is particularly likely unless banks start rejecting old IPinside versions and requiring users to update.

Does IPinside actually make banking safer?

Interezen isn’t merely providing the IPinside agent application. According to their self-description, they are a company who specializes in BigData. They provide the service of collecting and analyzing data to numerous banks, insurances and government agencies.

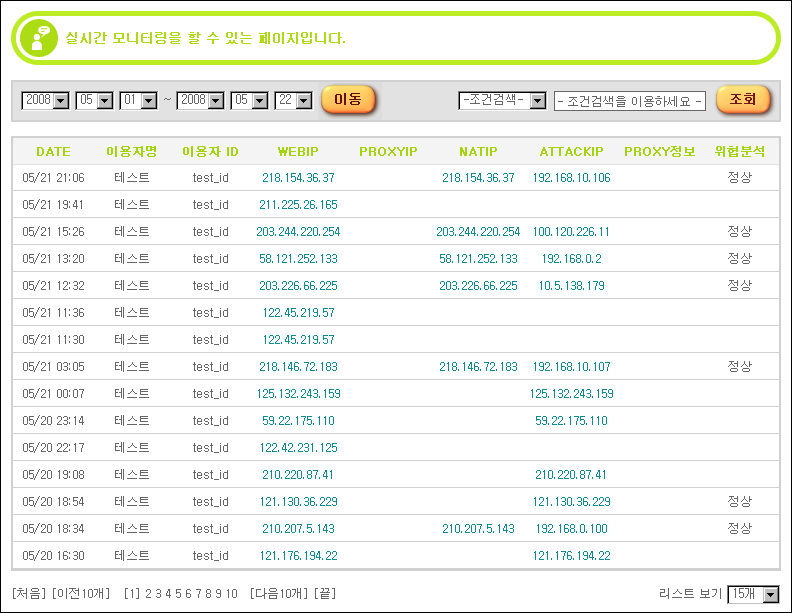

Online I could find a manual from 2009 showing screenshots from Interezen’s backend solution. One can see all website visitors being tracked along with their data. Back in 2009 the application collected barely more than the IP addresses, but it can be assumed that the current version of this backend makes all the data provided by the agent application accessible.

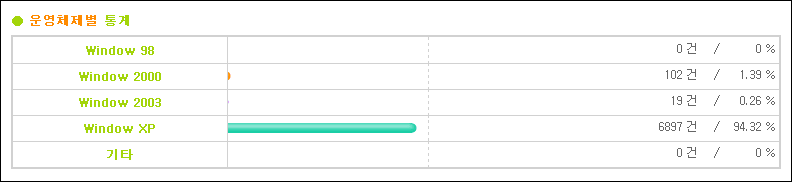

In addition to showing detailed information on each user, in 2009 this application was already capable of producing statistical overviews based e.g. on IP address, location, browser or operating system.

The goal here isn’t protecting users, it’s protecting banks and other Interezen customers. The idea is that a bank will have it easier to detect and block fraud or attacks if it has more information available to it. Fraudsters won’t simply be able to obfuscate their identities by using proxies or VPNs, banks will be able to block them regardless.

In fact, Interezen filed several patents in Korea for their ideas. The first one, patent 10-1005093 is called “Method and Device for Client Identification.” In the patent filing, the reason for the “invention” is the following (automatic translation):

The importance and value of a method for identifying a client in an Internet environment targeting an unspecified majority is increasing. However, due to the development of various camouflage and concealment methods and the limitations of existing identification technologies, proper identification and analysis are very difficult in reality.

It goes on to explain how cookies are insufficient and the user’s real IP address needs to be retrieved.

The patent 10-1088084 titled “Method and system for monitoring and cutting off illegal electronic-commerce transaction” expands further on the reasoning (automatic translation):

The present invention is a technology that enables real-time processing, which was impossible with existing security systems, in the detection/blocking of illegal transactions related to all e-commerce services through the Internet, and e-commerce illegal transactions that cannot but be judged as normal transactions with existing security technologies.

This patent also introduces the idea of forcing the users to install the agent in order to use the website.

But does the approach even work? Is there anything to stop fraudsters from setting up their own web server on localhost:21300 and feeding banking websites bogus data?

Ok, someone would have to reverse engineer the functionality of the IPinside LWS Agent application and reproduce it. I mean, it’s not that simple. It took me … checks notes … one work week, proof of concept creation included. Fraudsters certainly don’t have that kind of time to invest into deciphering all the various obfuscation levels here.

But wait, why even go there? A replay attack is far simpler, giving websites pre-recorded legitimate responses will just do. There is no challenge-handshake scheme here, no timestamp, nothing to prevent this attack. If anything, websites could recognize responses they’ve previously seen. But even that doesn’t really work: ndata and udata obfuscation has no randomness in it, the data is expected to be always identical. And wdata has only one random byte in its obfuscation scheme, that’s not sufficient to reliably distinguish legitimately identical responses from replayed ones.

So it would appear that IPinside is massively invading people’s privacy, exposing way to much of their data to anybody asking, yet failing short of really stopping illegal transactions as they claim. Prove me wrong.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/OeAPtFc

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.