As David Klinghoffer noted, this past Sunday evening I had a very enjoyable time going on Coast to Coast AM with host George Noory. Say what you will about some of the offbeat topics covered by this extremely popular overnight radio show. Yet a lot of serious scientists have been on with Mr. Noory. He is a fantastic host and gifted at bringing people with diverse views and backgrounds together to have a fun, friendly, but substantive conversation.

In the second hour Noory took phone calls from listeners. One of the callers was a longtime regular on the show named Walter who offered an argument for evolution based upon the famous idea that “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny.” I said to Walter that I was not at all surprised he had learned that this was a strong argument for evolution, as in the past it had been taught for many years to students.

When I was younger, my family lived next-door to a curmudgeonly but friendly retired dentist named Max. He passed away a few years ago, but I have many fond memories of him. Before entering dentistry, Max studied biology at UC Berkeley. That was in the earlier part of the 20th century. He was also a strong believer in Darwinian evolution. One day I asked Max why he supported evolution and he said, “Don’t you know Casey? It’s because ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny!”

Ernst Haeckel and Charles Darwin

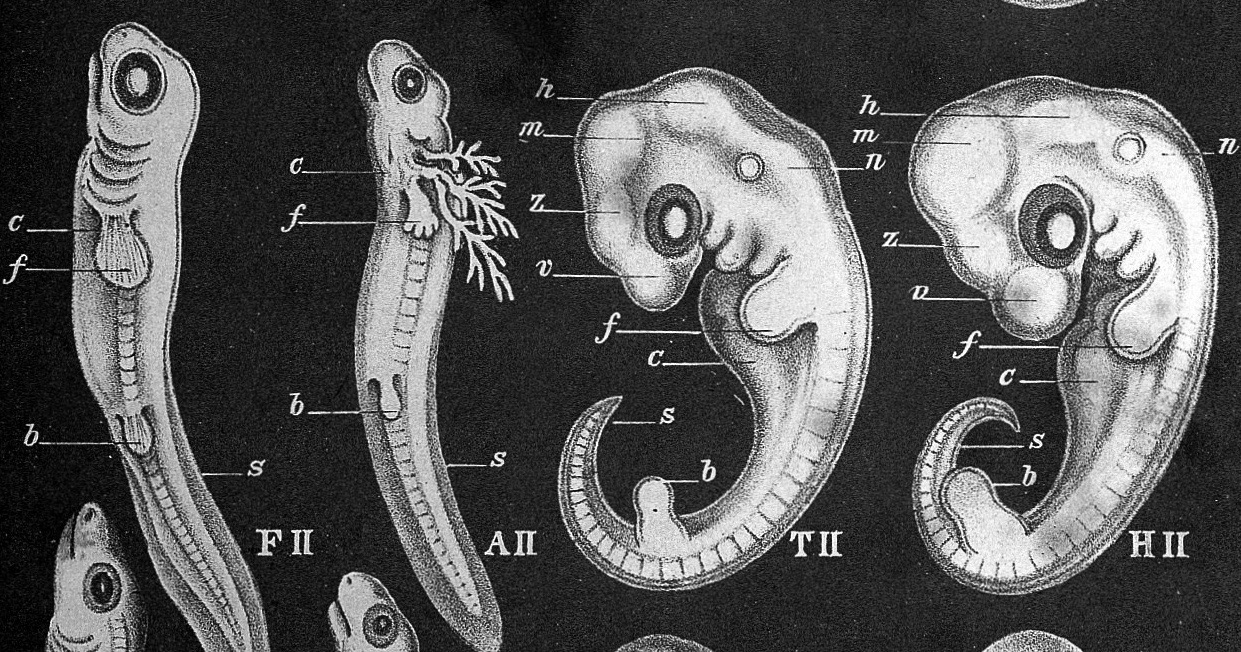

Max was referring to recapitulation theory, popularized in 1866 by the influential German biologist Ernst Haeckel — a follower of Charles Darwin. The theory holds that the development of an organism (ontogeny) replays (recapitulates) its evolutionary history (phylogeny).

Haeckel taught that, over eons of time, certain fish evolved into amphibians, some of which evolved into reptiles. In turn, some reptiles evolved into birds, and others into mammals. Recapitulation theory holds that each embryo of higher life forms replays its presumed ancestral history as it develops. In other words, at one point between your conception and birth, you resembled a fish (in its embryonic stage).

How UC Berkeley Evolved

For decades, this concept was taught as fact, although for well over a hundred years it has been known to be false. Indeed, the evidence shows that vertebrate embryos do not replay their supposed earlier evolutionary stages. Since Max learned at Berkeley that “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny,” you might wonder how that university’s views on the subject have themselves evolved. Here is a current excerpt from UC Berkeley’s pro-evolution website Understanding Evolution:

Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny…or does it?

The evolutionary study of embryos reached a peak in the late 1800s thanks primarily to the efforts of one extraordinarily gifted, though not entirely honest, scientist named Ernst Haeckel (left). Haeckel was a champion of Darwin, but he also embraced the pre-Darwinian notion that life formed a series of successively higher forms, with embryos of higher forms “recapitulating” the lower ones. Haeckel believed that, over the course of time, evolution added new stages to produce new life forms. Thus, embryonic development was actually a record of evolutionary history. The single cell corresponded to amoeba-like ancestors, developing eventually into a sea squirt, a fish, and so on. Haeckel, who was adept at packaging and promoting his ideas, coined both a name for the process — “the Biogenetic Law” — as well as a catchy motto: “Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny.”

Haeckel was so convinced of his Biogenetic Law that he was willing to bend evidence to support it. The truth is that the development of embryos does not fit into the strict progression that Haeckel claimed. Echidnas, for example, develop their limbs much later than most other mammals. But in his illustrations of echidna embryos, Haeckel deceptively omitted limb buds at early stages, despite the fact that limb buds do exist then. In Haeckel’s own day, some biologists recognized his sleights of hand, but nevertheless the Biogenetic Law became very popular, and Haeckel’s illustrations even found their way into biology textbooks.

The biogenetic law is broken

By the turn of the century, scientists had discovered many cases that defied Haeckel’s so-called law. His followers tried to cast them as exceptions that proved the rule. But Haeckel’s final downfall came with the rise of genetics and the modern synthesis. Haeckel, after all, was promoting a basically Lamarckian notion that evolution had a built-in direction towards “higher” forms. But genes, it was soon discovered, controlled the rate and direction of embryonic development. Individual genes can mutate and cause different changes to the way embryos grow — either adding new stages at any point along their path, or taking them away, speeding up development or slowing it down.

Embryos do reflect the course of evolution, but that course is far more intricate and quirky than Haeckel claimed. Different parts of the same embryo can even evolve in different directions. As a result, the Biogenetic Law was abandoned, and its fall freed scientists to appreciate the full range of embryonic changes that evolution can produce — an appreciation that has yielded spectacular results in recent years as scientists have discovered some of the specific genes that control development. [All emphases added.]

A Pro-Evolution Spin

Of course the article puts a pro-evolution spin on the data. But the point is that the idea that “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” is equated with the “Biogenetic Law” and the article says that this law is “broken” and has been “abandoned” by scientists today.

As another example, consider this excerpt from UC Berkeley’s Evolution 101 website, on the page devoted to “Ontogeny and Phylogeny”:

Not recapitulation

In the late 1800s some scientists felt that ontogeny not only could reveal something about evolutionary history, but that it also preserved a step-by-step record of that history. These scientists claimed that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny (ORP). This phrase suggests that an organism’s development will take it through each of the adult stages of its evolutionary history, or its phylogeny. At the time, some scientists thought that evolution worked by adding new stages on to the end of an organism’s development. Thus its development would reiterate its evolutionary history — ontogeny recapitulating phylogeny.

This idea is an extreme one. If it were strictly true, it would predict, for example, that in the course of a chick’s development, it would go through the following stages: a single-celled organism, a multi-celled invertebrate ancestor, a fish, a lizard-like reptile, an ancestral bird, and then finally, a baby chick.

Ontogeny recapitulating phylogeny

This is clearly not the case — a fact recognized by many scientists even when the idea of ontogeny recapitulating phylogeny was introduced. If you observe a chick’s development, you will find that the chick embryo may resemble the embryos of reptiles and fish at points in its development, but it doesn’t recapitulate the forms of its adult ancestors.

Even on a smaller scale, ORP is often untrue. For example, the axolotl evolved from a salamander ancestor that had internal gills in the adult stage. However, the axolotl never develops through a stage with internal gills; its gills remain external in flagrant violation of ORP.

If ORP were completely true, it would certainly make constructing phylogenies a lot easier. We could study an organism’s development and read its history directly. Unfortunately, phylogeneticists are out of luck here.

Again, we see that phylogeneticists seeking to study embryology to understand evolutionary history are “out of luck.”

“Fraud Rediscovered”

Despite these problems with Haeckel’s Biogenetic Law, there are many people like Max and Walter who learned about recapitulation theory in school — and still believe it’s true. These people tend to be sincere folks who may have spent decades of their lives not knowing that the evidence they were taught in support of evolution was false. It’s a testament to what the journal Science has said in an article frankly titled, “Haeckel’s Embryos: Fraud Rediscovered”: “Generations of biology students may have been misled by a famous set of drawings of embryos published 123 years ago by the German biologist Ernst Haeckel.” Some may change their minds, some may not. Either way, people like Max and Walter should be approached gently and respectfully — honoring those who have come before us and who helped build the world we live in today.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/mDH9u10

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.