Readers of my occasional autobiographical posts will know that I came of age in the late 1960’s and early 1970s and was a fully-fledged member of the drug freak generation. Indulging freely in a wide range of illicit substances, something I neither regret nor overly value; it was how it was. However, always the born historian, when my drug freak colleagues were busy lighting up that spliff or dropping that tab, I was also busy reading up on the report of the 1894 Indian Hemp Drugs Commission or the Scythian shamans use of cannabis or Albert Hofmann’s synthesis of LSD at Sandoz or the medieval outbreaks of St Anthony’s Fire caused by ergot-based drugs. In other words I didn’t just want to get high but also to discover the history of humans getting high.

Later in my life during the time that I managed the monthly #histsci blog carnival On Giants’ Shoulders and then ran the weekly #histsci journal Whewell’s Gazette I regularly read a lot of blogs and one blog that I very much enjoyed was Benjamin Breen’s Res Obscura. Though not strictly a #histsci blog Res Obscura is a wonderful cornucopia of erudite, entertaining, enlightening and educational essays about, well, obscure things as the blog name says.

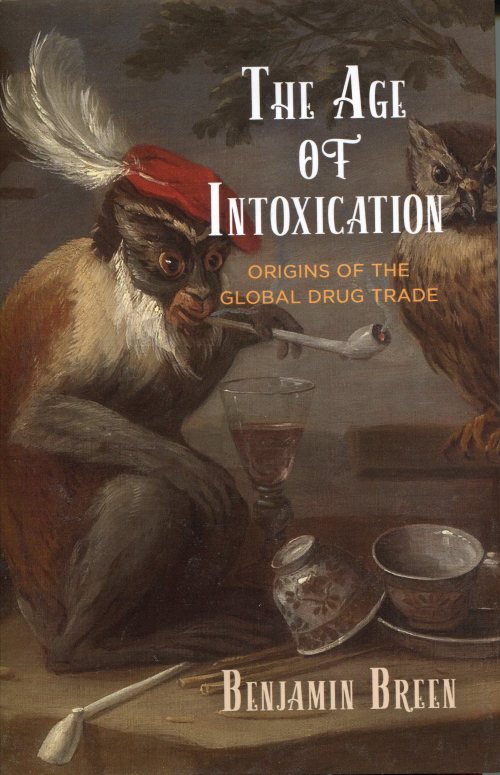

Given this two rather disparate aspects of my life I was delighted when I discovered that Benjamin Breen had written and published a book with the title, The Age Of Intoxication: Origins of the Global Drug Trade. I knew that this was a book that I wanted to read and read it I have and it has fulfilled all my expectations.

Now it might seem at first glance that my youthful adventures in the age of sex and drugs and rock’n’roll and Breen’s academic opus about the beginnings of the global drug trade in the early modern period would have little or nothing in common but appearances can be deceptive and in this case they are. One of Breen’s central themes in his book is that the dichotomies that characterised the world of drugs in the 1960s and 70s, medical–recreational, legal–illicit, natural–synthetic were in fact created during the European confrontation with exotic new drugs from South America and Asia during the Early Modern Period, which shaped the way we see intoxicants today.

Early in his book Breen explains to the reader, or in my case reminds him, that the word drug originally meant dry goods, as is still obvious in the North American drugstore or the German Drogeriemarkt. This meant that the “drugs” that the early European trader–explorer brought back home from all over the world included not only what we would now call drugs but also a very diverse range of other goods, including herbs and spices, dyes, soaps, incenses, pigments or even jewels. Although, one should add than many of these non drug dry good were often also regarded as medicines. One should also remember that three of our everyday commodities, coffee, chocolate and tobacco, were originally viewed as medicinal drugs.

Breen narrative centres around two of the early European empires the Portuguese and the English, as the main sources for the introduction and establishment of intoxicant drugs into European culture. The book is divided into two sections. The first of these, entitled Invention of Drugs, begins with the Portuguese search of new drugs in the jungles of Brazil, inspired by the discovery of quinine, the ground up bark of the cinchona tree, by the Jesuits in Peru. We then move on to the selling of the new drugs in the Apothecaries of Europe. This section closes with a fascinating discussing Fetishizing Drugs about the relationship between drug use, religion and magic in Early Modern Africa.

The second section, Altered States, tackles the whole concept of intoxication. It opens with the strange, under the counter so to speak, relationship between the Portuguese, oft Jesuit, discoverers and importers of drugs and the natural philosophers of the English Royal Society. This exchange of information and knowledge, whilst for a period highly active, remained largely clandestine because of the religious, political and philosophical clash that existed publically between the two parties. But the exchange did take place and was highly fruitful. Historians of science in the know will perhaps be aware of Robert Hooke’s dope smoking activities but as Breen shows there was very much more. We now move on to the problems involved in trying to describe and classify states of intoxication. The only real reference point for the Europeans was getting drunk on alcohol, whereas the highs produced by the alkaloids contained in the drugs imported from South America and Asia are very different. I know this from personal experience. Try explaining an acid trip to somebody whose only experience of deliberately losing control of ones mental facilities is getting pissed!

The second section closes with what might within the context of the book be described as a case study. Entitled Three Ways of Looking at Opium it chronicles how the perception and acceptance of opium changed between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. Breen starts with a fact that was completely new to me, the opium poppy is actually a native European plant and the perception that opium comes into Europe from Asia is one of those changes that took place in the early modern period. Breen relates how a fairly positive image of opium as a medicinal drug gradually changes to a negative one, a process accelerated in the nineteenth century by the successful synthesis of the of first morphine and later heroine from raw opium; the synthetic forms becoming the acceptable medical drugs, whereas raw opium becomes an unacceptable illicit substance.

The book closes with a meditation on our attitude to drugs then and now under the title, Drugs Past and Present.

This is a truly polymathic, historical achievement; Breen weaves together a world history out of elements of the social, cultural and core histories of exploration, discovery, botany, chemistry, medicine, pharmacology, trade, economics, magic, religion and philosophy. As was to be expected from the author of Res Obscura this book is beautifully written and is a real pleasure to read. It is well presented with a wide range of grey in grey illustrations. There are extensive, highly informative endnotes, requiring the somewhat tiresome two bookmarks method of reading, a useful bilingual (Portuguese and English) glossary, a very comprehensive bibliography and an excellent index.

Whatever your historical interests, if you like reading good quality, excellently researched and equally excellently written history, then do yourself a favour and read Breen’s fascinating academic excursion through the world of the Early Modern drug trade.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/39z46IC

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.