Ramanujan’s First Letter to G.H. Hardy

On or about the 31st of January 1913, mathematician G.H. Hardy of Trinity College at Cambridge University received a parcel of papers from Madras, India which included a cover letter from an aspiring young Indian mathematician by the name of Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887–1920). The cover letter discussed three topics:

- An introduction of Ramanujan and his precarious situation;

- A claim about the domain of the gamma function; and

- A claim about the distribution of prime numbers;

This essay provides an overview of the mathematical content of Ramanujan’s first letter, as well as Hardy’s reaction and response.

The Cover Letter

Ramanujan’s letter may be divided into four paragraphs, covering essentially three topics: 1. An introduction of who he is; 2. A discussion of the gamma function for negative and fractional values; and 3. A discussion of the distribution of prime numbers.

The First Paragraph

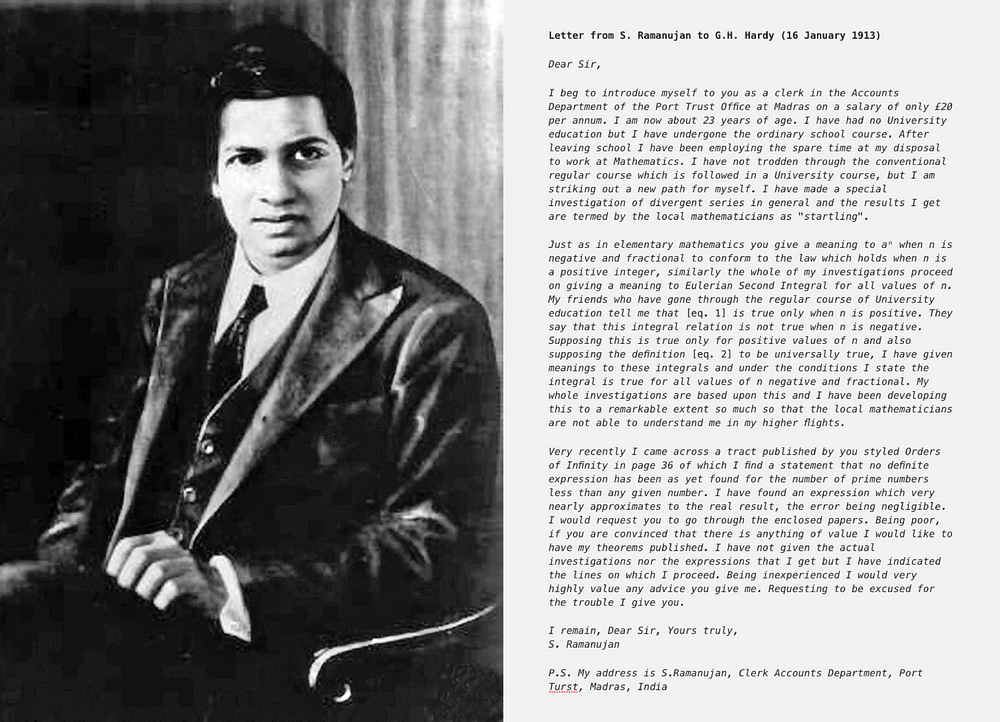

Dear Sir,

I beg to introduce myself to you as a clerk in the Accounts Department of the Port Trust Office at Madras on a salary of only £20 per annum. I am now about 23 years of age. I have had no University education but I have undergone the ordinary school course. After leaving school I have been employing the spare time at my disposal to work at Mathematics. I have not trodden through the conventional regular course which is followed in a University course, but I am striking out a new path for myself. I have made a special investigation of divergent series in general and the results I get are termed by the local mathematicians as "startling".

As Kanigel (1991) writes, such an introduction was perhaps intended to incite both pity and wonder in Hardy, then 36 years old and generally recognized as the leading English pure mathematician of his time (Berndt & Rankin, 1995).

The Second Paragraph

By the second paragraph however, Ramanujan was already getting to the point of his inquiry by suggesting that he could give meaning to negative values of the so-called gamma function:

Just as in elementary mathematics you give a meaning to aⁿ when n is negative and fractional to conform to the law which holds when n is a positive integer, similarly the whole of my investigations proceed on giving a meaning to Eulerian Second Integral for all values of n. My friends who have gone through the regular course of University education tell me that

is true only when n is positive. They say that this integral relation is not true when n is negative. Supposing this is true only for positive values of n and also supposing the definition

to be universally true, I have given meanings to these integrals and under the conditions I state the integral is true for all values of n negative and fractional. My whole investigations are based upon this and I have been developing this to a remarkable extent so much so that the local mathematicians are not able to understand me in my higher flights.

Ramanujan is referring to the analytic continuation of the gamma function, despite seemingly having no knowledge of the well-known technique’s existence. Yet still, his definition of Γ(n) is precisely what one obtains if he had known of it (Berndt & Rankin, 1995).

The gamma function Γ(n) Ramanujan referred to has been an important object of study since the problem of extending the factorial function to non-integer arguments was studied by Daniel Bernoulli and Christian Goldbach in the 1720s. It is an extension of the factorial function n! (1 x 2 x 3 x 4 x 5 x …. n), shifted down by 1:

Its plot is very curious:

Here shown as the function of a variable z. Even 50 years before Ramanujan’s time the gamma function was known to be defined for all complex values of z larger than zero. Complex numbers, as you probably know, are a class of numbers with an imaginary part, written as Re(z) + Im(z), where Re(z) is the real part (ordinary real number) and Im(z) is the imaginary part, denoted by the letter i. A complex number is typically written in the form z = σ + it where sigma σ is the real part and it is the imaginary part. Complex numbers are useful because they allow mathematicians and engineers to evaluate and work on problems where ordinary real numbers will not allow it. Visualized, complex numbers extend the traditional one-dimensional “number line” into a two-dimensional “number plane”, called the complex plane, in which the real part of a complex number is plotted on the x-axis and the imaginary part is plotted on the y-axis (Veisdal, 2016). In order to be able to use the gamma function Γ(z), it is typically rewritten to the form:

Using this identity, one can obtain values for z below zero. It does not however give values for negative integers, as they are not defined (technically they are singularities, or simple poles). This is where analytic continuation comes in, and where Ramanujan’s first investigation had taken him.

The Third Paragraph

Very recently I came across a tract published by you styled Orders of Infinity in page 36 of which I find a statement that no definite expression has been as yet found for the number of prime numbers less than any given number. I have found an expression which very nearly approximates to the real result, the error being negligible. I would request you to go through the enclosed papers.

Ramanujan in this third paragraph goes on to address the seemingly completely separate issue of the distribution of prime numbers (although, the two topics are actually related, as shown by Bernhard Riemann in his 1859 paper Ueber die Anzhal der Primzahlen unter einer gegebenen Grösse, “On prime numbers less than a given magnitude”).

Ramanujan’s claim about finding an expression for the number of prime numbers less than a given number had also been tackled before, perhaps most prominently by four mathematicians: Gauss, Legendre, Dirichlet and Riemann. A prime counting function π(n) gives the number of primes less than or equal to a given real number. Given that there is no known formula for finding primes, the prime counting formula is known to us only as a plot, or step function increasing by 1 whenever x is prime. The plot below shows the function up to x = 200 (Veisdal, 2016):

Gauss considered the question of how many primes there below a given number when at the age of 15 or 16 in 1792–93. Legendre slightly later, in 1797–98 conjectured (based on prime number tables by Felkel and Vega) that a prime counting function π(n) is approximated by the function

where A and B are unspecified constants. He later approximated them to be A = 1, B = -1.08366. Both Gauss and Legendre’s prime-counting functions imply what is known as the prime number theorem, namely that:

Which in English states “As x goes to infinity, the prime counting function π(x) will approximate the function x/ln(x)”. In other words, if you count high enough, and plot the number of primes up to a very large number x, then plot x divided by the natural logarithm of x, the ratio between the two will approach 1. The two functions are plotted below for x = 1000:

Dirichlet later formulated his own approximation, which is better than that provided by Legandre and Gauss, known now as the logarithmic integral function Li(x):

Plotting this function alongside the prime counting function and the formula from the prime number theorem, we see that Li(x) is actually a better approximation than x/ln(x):

As pointed out by Berndt & Rankin (1995), Ramanujan’s claimed approximation for the prime counting function π(x) were much less precise than he believed, but still remarkable given his limited access to existing theory.

The Fourth Paragraph

Being poor, if you are convinced that there is anything of value I would like to have my theorems published. I have not given the actual investigations nor the expressions that I get but I have indicated the lines on which I proceed. Being inexperienced I would very highly value any advice you give me. Requesting to be excused for the trouble I give you.

I remain, Dear Sir, Yours truly, S. Ramanujan

In the pages that followed Ramanujan’s one-page cover letter, the Indian mathematician would go on to provide at least 11 more pages (at least two of which are now lost) containing technical results in topics ranging from work on infinite series and the gamma function, the distribution of prime numbers, hypergeometric series, continued fractions, elliptic functions, Bromwich’s infinite series, divergent functions, a discussion of the Bernoulli numbers and more.

Hardy’s reaction

Certainly the most remarkable [letter] I have ever received, its author a mathematician of the highest quality, a man of altogether exceptional originality and power.

Ramanujan’s letter would be the first of numerous written communications between himself and G.H. Hardy, which would culminate in the invitation by Hardy for Ramanujan to come to Trinity College, Cambridge to work with him, which Ramanujan did in 1914.

Upon receiving the Ramanujan’s first letter however, Hardy was initially skeptical. As Kanigel (1991) writes:

"For Hardy, Ramanujan's pages of theorems were like an alien forest whose trees were familiar enough to call trees, yet so strange they seemed to have come from another planet; it was the strangeness of Ramanujan's theorems that struck him first, not their brilliance. The Indian, he supposed, was just another crank."- Excerpt, The Man Who Knew Infinity by Robert Kanigel (1991)

However, after having “put the manuscript aside and lost himself in the day’s London Times”, “set to work on mathematics, kept at it until about one, then ambled over to Hall for lunch” and next been “off to the university courts on Grange Road for a game of “real” tennis” (Kanigel, 1991),

“The Indian Manuscript scraped and tugged at his composure with, as Snow (1966) wrote, its “wild theorems. Theorems such as he had never seen before, nor imagined”.

After going back to read Ramanujan’s manuscripts again and seeing his theorem on continued fractions on the last page, Hardy is to have said that they “defeated me completely; I had never seen anything in the least like them before”. He asked his colleague and collaborator J. E. Littlewood (1885–1977) to take a look at the papers. Littlewood’s reaction was amazement at the Indian’s genius, leading Hardy to conclude that the letter was “certainly the most remarkable I have received” and that Ramanujan was “a mathematician of the highest quality, a man of altogether exceptional originality and power” (Hardy, 1920).

Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) later wrote that by the next day he “found Hardy and Littlewood in a state of wild excitement because they believed they had found a second Newton, a Hindu clerk in Madras making 20 pounds a year”.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2ThewXi

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.