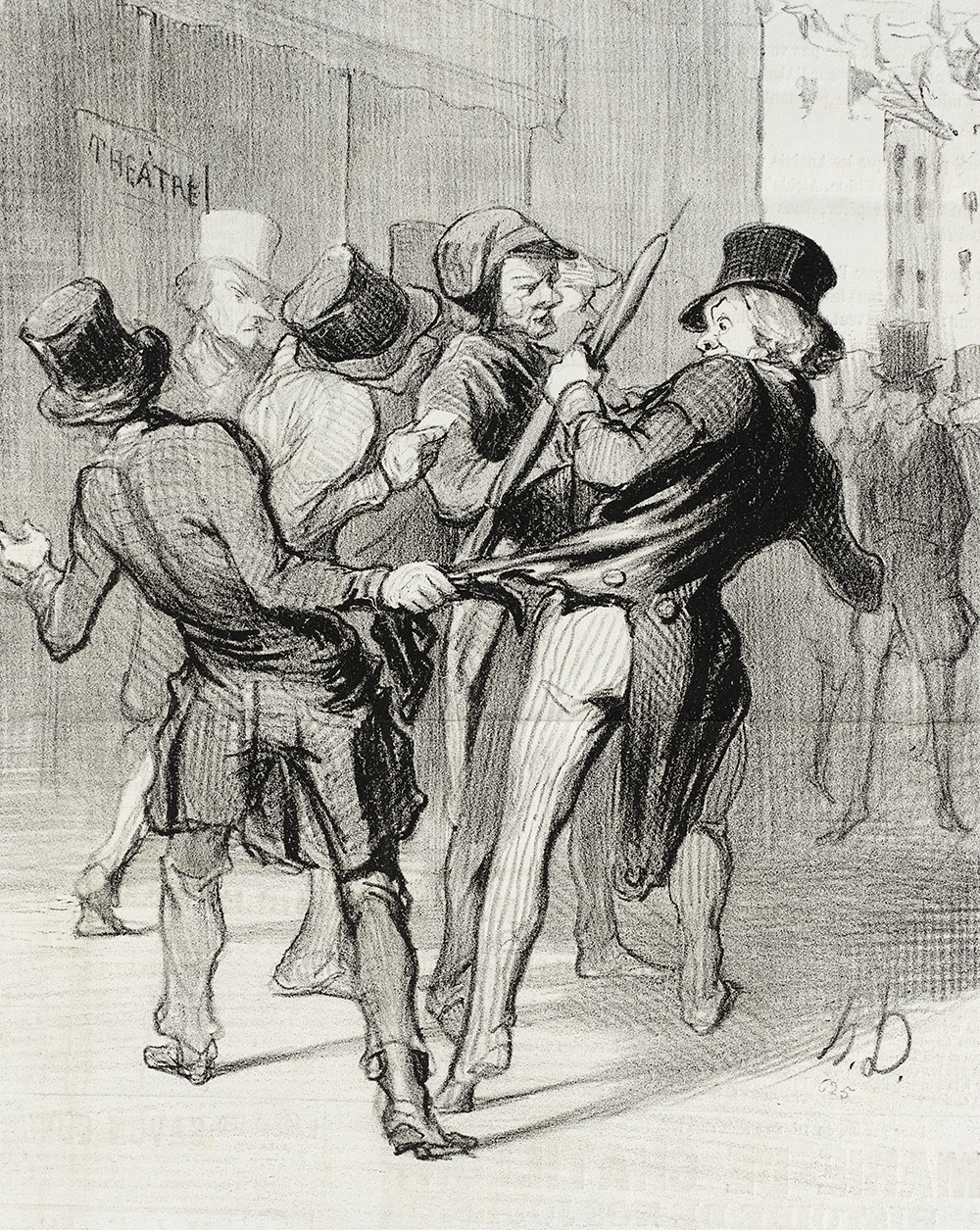

On November 18, 1850, a Monsieur Langangne decided he had had enough and took up his pen to write a letter to the police. Having the habit of taking an evening walk “en flâneur” from the Madeleine to the Faubourg Montmartre in what was then the first arrondissement (now the eighth), Langangne wrote that he had begun to notice “spectacles of shameful immorality that have painfully afflicted my sight and my spirit.” These spectacles, he specified, were none other than “those offered by those beings without name, those hideous hermaphrodites!” He explained that so long as their behavior remained within “certain limits, he kept quiet, but that is impossible now that the activities of these unfortunates (who no doubt also portray themselves as advocates of the right to work, since bad examples are contagious) reach the alarming heights of organized blackmail.” Indeed, Langangne proceeded to describe how, the previous day, he was “accosted” by two young men with “cheeks painted with makeup,” who claimed to know him and who asked him to buy them some drinks. Surmising that the reason they approached him was that “he may have something in common with one of their brothers or friends,” Langangne refused, which led the two men to launch a series of insults at him. This unpleasant encounter convinced this particular Parisian that “the boulevards are currently a veritable court of miracles planted in the middle of Sodom and Gomorrah, and soon all promenades on them will be forbidden not only to honest women who have not been able to show themselves for a long time, but also for men who should not have to be at odds with rascals.”

As an employee within the Ministry of Finance, Langangne seemed to expect that the streets were in some ways “his.” His right to them certainly outweighed that of those “hermaphrodites,” a faith indicated by his self-identification as a “flâneur.” The idea of the “flâneur” encapsulates a form of urban wandering predicated on class and gender privilege that permitted movement and observation of the attractions of modern city life. The act of flânerie depended on the management and maintenance of perception, the clear control over what one saw and heard, as well as one’s response. More broadly, as scholar Vanessa Schwartz has described it, the flâneur represents “a positionality of power—one through which the spectator assumes the position of being able to be part of the spectacle and yet command it at the same time.”

By asserting himself as a “flâneur,” then, Langangne referenced a whole host of assumptions about his place within the urban environment, all of which revolved around his ability to move about, look on, and assert himself within urban space as he wished.

Langangne was not entirely successful at asserting his own respectability against the disrepute of the men he encountered. The letter notes, after all, that he was only writing because the hermaphrodites’ behavior had exceeded “certain limits.” Presumably, in other words, they had been present before this moment, fixtures of a broader neighborhood culture that became an annoyance once they specifically targeted him. In addition, his admission that the “hermaphrodites” may have addressed him because “he may have something in common with” them highlights his difficulty in distinguishing his own identity from those who accosted him.

Although the letter may have tried to construct the writer’s knowledge against the supposed ignorance of its objects, that knowledge was, in fact, premised on Langangne’s own familiarity with his targets: he knew how to recognize them through their behavior and dress. That he may have “resembled” them reinforces the difficulty he faced in separating himself. He could know who they were only if he was in some sense already one of them. The “straight” flâneur thus becomes decidedly queer, because we can ultimately never know who he was: a victim or a participant in a culture of public sex.

The use of public space for sex should not be seen only in terms of anxiety by regulators and Parisians, but also as a practice that actively shaped the ways people encountered urban space.

During this period, expert commentators, the police, and lay Parisians believed that sex was increasingly available and unavoidable on the streets of Paris. At the same time, the redevelopment of the city oriented it even more toward its image as a site of commercial “pleasure.” This combination—an emphasis on the dangers of public sex and a social world that revolved around seeking out public pleasure—made sexual knowledge more essential to experiencing the city at the very time when it seemed that sex was escaping its boundaries. As the brothels failed and men who sought sex with other men were more apparent, the need to recognize the possibility of a sexual encounter, whether in order to pursue or avoid one, became more important. Public sex, therefore, should not be seen as an “other” practice against which “dominant” “norms” were defined, but rather as one way the city emerged in the first place. The need to know how to understand the possibility of encountering public sex disrupts any easy division between supposedly “illicit” forms of public sexuality and “licit” forms of social practice. Such a distinction, rarely named but often implied, never actually cohered.

As Haussmannization oriented the city around the flow of capital, commerce, and the middle classes, the congruence between sex and commercial pleasure became increasingly problematic as the police and expert commentators considered the regulation of urban space. It was one thing to accept the presence of venal and immoral sex in areas of the city already associated with working-class debauchery as a necessary safety valve. It was another when such practices took center stage in spaces devoted to middle-class and elite Parisian consumption.

And while it is difficult to precisely map the areas of the city where such encounters occurred, both the police and many Parisians began to see sex everywhere they looked. Encounters premised on these forms of sexual knowledge created a new sexual public.

Sexual solicitation had wider ramifications for how users of public space understood their own role. For instance, an 1872 letter complained that “an honest man can no longer walk peacefully on the cours la Reine [near the Champs-Élysées] between 9 and 11 at night without being accosted by women who engage in revolting touches and direct the following verbatim proposition (Do you want me to jack you off?).” The writer apologized for using such explicit language, “but it has been used by many of the ignoble creatures.” That these encounters bothered him enough to write, that they stayed with him after he moved on, highlights the ways sexual solicitation created new feelings and emotions that were anything but momentary.

The letter stands as evidence of the creation of a broader sexual public (who else heard these words?) even as it highlights how the individual writer’s sense of self changed in some undefinable way in response to the encounter. In another instance, a man named G. Feuille wrote to the police in 1880 to complain: “It is scandalous…to see oneself attacked (assaili) and almost violated (violenté) by several prostitutes, who direct at you the most filthy remarks.” The violation implied here may not have actually been sexual assault as the French word violenté may imply, but the connotation remains significant. That this man felt sexually assaulted by women who put themselves at the service of male clients highlights the inversion at play as men were forced to reckon with their own sexual response. In both cases, the unwilling participation in a public sexual culture threatened the urban experience as imagined by privileged male pedestrians.

The “violation” felt by these two men at the attention of female prostitutes disrupted their ability to move about the city as they so chose, but it did not necessarily put into question their status as potential clients. Insofar as these “assaults” may have elicited a sexual response, they may have heightened their awareness of their status as sexual beings even as it challenged their gender privilege.

These possibilities often proved problematic for women who wished to also enjoy public space. An 1872 letter signed by multiple residents of the boulevard de la Villette, for instance, claimed that the street was so encumbered that a wife and child could not exit their house without being taken as prostitutes by men who were constantly on the lookout. The expectation that sex was available thus shaped how these residents were understood by those who saw them. As others have argued, the common assumption that a woman in public was a public woman placed all women, but especially working-class women, in a vulnerable position. The emphasis on the threat of the prostitute by the police and Paris residents tended to increase the association of public space with the possibility of venal sex, which, in turn, shaped how women encountered the life of the city. This is not to say that all women who appeared in public were assumed to be sexually available, nor that middle-class women were forbidden from the streets. The streets enabled a wide variety of encounters, dependent on the particular circumstances in which they occurred.

In fact, rather than two possible categories—honest and dishonest—into which an unsuspecting woman could fall, movement about the city made such categorizations highly contingent. For example, on the evening of January 19, 1874, two police inspectors arrested a woman named Valerie Durand, a thirty-three-year-old piano teacher. According to the police, the officers were taking a prostitute to the station when they came across “a woman, alone, standing in the middle of the boulevard, next to a garden where they claimed to have seen her address several individuals.” One of the officers then turned to his partner, “saying to him, ‘Look over there, since you know the women of this neighborhood better than me, if that’s an unregistered prostitute.’ ”1 The partner, so the police claimed, decided to approach the woman only after “recognizing that she was looking at men in a provocative manner.” Asked what she was doing there, she responded by saying she was waiting for her husband and refused to give her name. She was then arrested and taken to the station, where she admitted to having lied about being married and “that in reality, she was waiting for a man who was employed in a factory, and, finally, that she was perfectly free to wait for whomever on the boulevard.” She claimed that she was on her way home when she was arrested after stopping to button herself up. During the course of her arrest, the officers refused to check her story at her home, or even by asking an acquaintance living in the same building as the commissariat of police, before sending her off to the depot. Police confidence in their ability to tell who was and who was not actually a prostitute, reliant on such vague attributes as a provocative glance, thus determined their will to act.

Durand’s situation on the one hand highlights women’s vulnerability. But on the other hand it illustrates the ways that the assumption of prostitution was never so stable as to totally delimit someone’s ability to act. For Durand’s actual identity was never fully determined in the police documents. Was she innocently returning home, as she claimed? Or was she waiting for a “male friend,” as she also claimed? Perhaps the police were right and she was actually looking for a sexual client. The police eventually let her go, but despite having received “the most favorable information on her family,” they still argued in favor of the “facts certified by the police agents.” Indeed, the police superintendent took the opportunity to assure his superiors that he would “be even more circumspect regarding unregistered prostitutes who are vouched for by honorable persons.” This indeterminacy enabled Durand to be released to her family not only without being condemned as a registered prostitute but also without admitting to being totally honest. Perhaps Durand was an innocent working woman out for a date who got caught up in an awful situation. But perhaps she was actually a prostitute able to use the thin line between her own profession and that of other (honorable) women to her advantage to get off the hook.

Although far from typical, this case of apparently false arrest demonstrates two essential aspects of the public sexual culture. On the one hand, the moral discourse of prostitution did leave women vulnerable. The public sexual culture remained hierarchical, predicated on gendered and classed relationships. But it also provided, on the other hand, if not evidence of the opportunity for resistance, then at least the possibility of a different understanding of sex in the modern city outside the binaries of honest and dishonest, registered and unregistered. The administrative category of the prostitute struggled to remain solid in the face of the uses of the street. Valerie Durand’s success at evading registration without falling into the category of the honest is but one example of the ways that late nineteenth-century sexual culture could not be slotted into a discrete set of categories.

1 Police categorized female prostitutes along two axes: they were either “registered” or “unregistered.” Registered prostitutes could be either filles en maison or filles isolées (also known as filles en carte, for the registration card they carried). The former were prostitutes who lived in a brothel, while the latter were those who lived outside one. Prostitutes were partly defined by their position vis-à-vis the tolerated brothel. ↩

Adapted from “Constructing a Public Sexual Culture” from Public City/Public Sex: Homosexuality, Prostitution, and Urban Culture in Nineteenth-Century Paris by Andrew Israel Ross. Used by permission of Temple University Press. © 2019 by Temple University. All rights reserved.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2nyyJKs

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.