Gillian Tindall is a high-minded Autolycus, devoted not merely to snapping up the “unconsidered trifles” of past lives but holding them to the light to glean the stories they might conceal. “Most objects, like all people, disappear in the end,” she writes at the start of The Pulse Glass, an excellent suite of essays on transience and remembrance. And yet not everything crumbles to dust; some bits and pieces defy the odds by surviving, and it is Tindall’s delight – albeit of a measured and low-key sort – to describe their escape from “the quiet darkness of forgetting”.

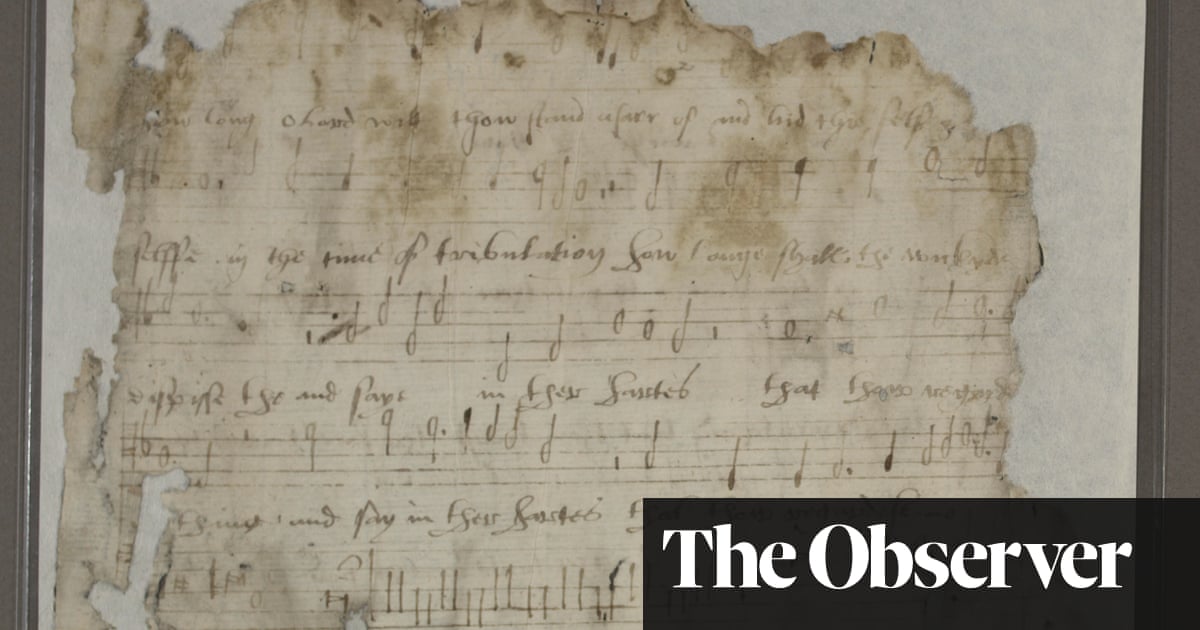

Take, for instance, the scrap of tightly folded paper recently discovered in the crack of a wall at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, possibly to stop up a draught; when examined, it turned out to be a fragment of a musical score by Thomas Tallis, from a service held in St Paul’s in 1544. Or the case of an attic clearance in Westminster Abbey where debris was found strewn across the floor. It was about to be tipped away when an archaeologist happened to notice many tiny shards of coloured glass mixed in there: closer study uncovered 30,000 fragments, which when put together revealed details of “exquisite workmanship” dating back to the 13th century – literally a window on a lost world.

Tindall herself is involved in some of the accidental recoveries. Offered the chance of a souvenir by a couple clearing out a French farmhouse near her own, the author found a small cardcase that held a cache of letters written to Célestine, an innkeeper’s daughter, in 1863-64. It inspired an earlier book of hers, Voices from a French Village, and made Célestine a posthumous local celebrity. The bequest of a tiny pulse glass – used by doctors prior to reliable watches – which once belonged to her great-great-grandfather Arthur Jacob (born 1795), unveils a portrait of her forebears that takes on darker hues as the book proceeds. The history of her house in north London, which she and her husband bought in 1963, is also reconsidered in the light of certain rackety Victorian occupiers and the building’s own semi-miraculous survival against developers and German bombs. It was much luckier than those East Enders whose displacement after the war Tindall saw at first hand while working for the Welfare Association in Stepney; the ageing tenants about to lose their homes “felt hurt in a profound, inarticulate way at what was being done, at the zero-value accorded to the very fabric of their lives”. Some losses really are irrecoverable.

Tindall has written, inter alia, a very good book about Kentish Town in north London (The Fields Beneath) and a brilliant one about George Gissing (The Born Exile), but I don’t think she has ever written as personally as she does here. “Personally” is a relative term, though, because one hears an austerity in her voice that repels any inclination to make friends with it. Beneath her historian’s fierce curiosity lies an obsessive, near-devotional spirit that puts the reader on guard – in another life she might have been an antiques dealer, or possibly a nun. The little elegy she writes to her lately deceased younger brother, an intensely private man, taps into a whole culture of mid-century English emotional reticence. Despite her quiet affection, Tindall calls him only “N”. Why not the honour of a name?

Loss was the terrible lifelong bond between them. When he was a schoolboy and she a teenager, their mother, Ursula, killed herself with an overdose in a stranger’s garage. A bright young thing at Oxford in the 1930s, later a promising novelist, Ursula seemed unable to cope with the legacy of a privileged upbringing and the five-year absence of her husband during the war. The horror of her suicide – a “betrayal of love and trust” – haunts the daughter still. For a time, she “avoided ever thinking about her”. Amid the many objects the author celebrates here – including keepsakes from her aunt and grandmother – there is nothing of her mother’s she has kept. No jewellery, no letters. “What will survive of us is love,” wrote Philip Larkin. It would take someone of severe integrity to deny that in the face of a parent’s ghost. Tindall, honest to a fault, is that person.

• The Pulse Glass by Gillian Tindall is published by Chatto & Windus (£16.99). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com. Free UK p&p over £15

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2RCD24k

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.